Heritage and Culture Report 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Make It Easier for You to Sell

We Make it Easier For You to Sell Travel Agent Reference Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE ITEM PAGE Accommodations .................. 11-18 Hotels & Facilities .................. 11-18 Air Service – Charter & Scheduled ....... 6-7 Houses of Worship ................... .19 Animals (entry of) ..................... .1 Jamaica Tourist Board Offices . .Back Cover Apartment Accommodations ........... .19 Kingston ............................ .3 Airports............................. .1 Land, History and the People ............ .2 Attractions........................ 20-21 Latitude & Longitude.................. .25 Banking............................. .1 Major Cities......................... 3-5 Car Rental Companies ................. .8 Map............................. 12-13 Charter Air Service ................... 6-7 Marriage, General Information .......... .19 Churches .......................... .19 Medical Facilities ..................... .1 Climate ............................. .1 Meet The People...................... .1 Clothing ............................ .1 Mileage Chart ....................... .25 Communications...................... .1 Montego Bay......................... .3 Computer Access Code ................ 6 Montego Bay Convention Center . .5 Credit Cards ......................... .1 Museums .......................... .24 Cruise Ships ......................... .7 National Symbols .................... .18 Currency............................ .1 Negril .............................. .5 Customs ............................ .1 Ocho -

ABSTRACT a Preliminary Natural Hazards Vulnerability Assessment

1 ABSTRACT A Preliminary Natural Hazards Vulnerability Assessment of the Norman Manley International Airport and its Access Route Kevin Patrick Douglas M.Sc. in Disaster Management The University of the West Indies 2011 The issue of disaster risk reduction through proper assessment of vulnerability has emerged as a pillar of disaster management, a paradigm shift from simply responding to disasters after they have occurred. The assessment of vulnerability is important for countries desiring to maintain sustainable economies, as disasters have the potential to disrupt their economic growth and the lives of thousands of people. This study is a preliminary assessment of the hazard vulnerabilities the Norman Manley International Airport (NMIA) in Kingston Jamaica and its Access Route, as these play an important developmental role in the Jamaican society. The Research involves an analysis of the hazard history of the area along with the location and structural vulnerabilities of critical facilities. Finally, the mitigation measures in place for the identified hazards are assessed and recommendations made to increase the resilience of the facility. The findings of the research show that the NMIA and its access route are mostly vulnerable to earthquakes, hurricanes with flooding from storm surges, wind damage and sea level rise based 2 on their location and structure. The major mitigation measures involved the raising of the Access Route from Harbour View Roundabout to the NMIA and implementation of structural protective barriers as well as various engineering design specifications of the NMIA facility. Also, the implementation of structural mitigation measures may be of limited success, if hazard strikes exceed the magnitude which they are designed to withstand. -

We Make It Easier for You to Sell

We Make it Easier For You to Sell Travel Agent Reference Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE ITEM PAGE Accommodations .................. 11-18 Hotels & Facilities .................. 11-18 Air Service – Charter & Scheduled ....... 6-7 Houses of Worship ................... .19 Animals (entry of) ..................... .1 Jamaica Tourist Board Offices . .Back Cover Apartment Accommodations ........... .19 Kingston ............................ .3 Airports............................. .1 Land, History and the People ............ .2 Attractions........................ 20-21 Latitude & Longitude.................. .25 Banking............................. .1 Major Cities......................... 3-5 Car Rental Companies ................. .8 Map............................. 12-13 Charter Air Service ................... 6-7 Marriage, General Information .......... .19 Churches .......................... .19 Medical Facilities ..................... .1 Climate ............................. .1 Meet The People...................... .1 Clothing ............................ .1 Mileage Chart ....................... .25 Communications...................... .1 Montego Bay......................... .3 Computer Access Code ................ 6 Montego Bay Convention Center . .5 Credit Cards ......................... .1 Museums .......................... .24 Cruise Ships ......................... .7 National Symbols .................... .18 Currency............................ .1 Negril .............................. .5 Customs ............................ .1 Ocho -

Jamaica Tourist Everything You Need to Know for the Perfect Vacation Experience

JAMAICA TOURIST WWW.JAMAICATOURIST.NET EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW FOR THE PERFECT VACATION EXPERIENCE ISSUE 14 - SPRING 2010 IN THIS ISSUE JOSS STONE SHINES AT 2010 JAMAICA JAZZ & BLUES FESTIVAL FANTASTIC GOLF EXPLORING JAMAICA THE ‘ONE LOVE’ PROJECT PALMYRA OWNERS TAKE OCCUPANCY OF LUXURY RESIDENCES CHULANI’S REMARKABLE JOURNEY TO JAMAICA HISTORIC TRAMWAYS OF KINGSTON THE GAP CAFÉ - JEWEL IN THE BLUE MOUNTAINS CUISINE FOR EVERY TASTE SHOPPING PAR EXELLENCE WHAT A GWAAN? OWN A TROPICAL HOME AT THE PALMYRA Look for the FREE GEMSTONE offer in the YOUR luxury shopping section! FREE ISSUE SEE ISLAND MAP INSIDE GROOVIN’ IN JAMAICA eople visit Jamaica for many reasons, one of which is the island’s many world-class music festivals that include Reggae Sumfest, Rebel Salute, Sting and perhaps the most popular, Jamaica Jazz & Blues Festival. From January 28 - 30, more than 20,000 Jazz and Blues aficionados flocked the lawns of the PTrelwany Multipurpose Stadium in Greenfield, for the 14th staging of the trendy event. Staged at the stadium for the first time this year, most skeptics were quickly won over by the ease of access and superior parking facilities of the venue, which comfortably hosted VIP tents, skyboxes, a craft market and a wide variety of food & beverage outlets. Combined with the world-class music line-up and masses of happy music lovers, the stadium formed a perfect venue. Visited by thousands of people at its former home Is This Love. Next, singer and songwriter Kenny ‘Babyface’ Edmonds entered the stage with a band dressed in at the iconic aqueduct of Rose Hall, the Jazz & Blues black tuxedos and paid homage to the ‘many beautiful women of Jamaica’ with classics like Every Time I Close Festival has seen outstanding performances by major My Eyes and My My My, Mama, Can We Talk For A Minute and I Wanna Rock With You Baby. -

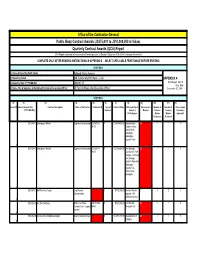

Quarterly Contract Awards (QCA) Report QCA Report Submitted to the Contractor General Pursuant to Section 4(2)(A) and 4(3) of the Contractor-General Act

Office of the Contractor-General Public Body Contract Awards (J$275,001 to J$10,000,000 in Value) Quarterly Contract Awards (QCA) Report QCA Report submitted to the Contractor General pursuant to Section 4(2)(a) and 4(3) of the Contractor-General Act COMPLETE ONLY AFTER READING INSTRUCTIONS IN APPENDIX B . SELECT APPLICABLE PRINT RANGE BEFORE PRINTING SECTION 1 (1) Name of Reporting Public Body National Works Agency (2) Reporting Period 2nd Quarter of 2009 (April - June) APPENDIX A (3) Reporting Date (YYYY-MM-DD) 2009-07-17 QCA Report. REV.5 Issue Date: (4) Name, Title & Signature of Certifying Principal or Accounting Officer Mr.Patrick Wong, Chief Executive Officer November 20, 2008 SECTION 2 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) Record # Contract Award Date Contract Description Name of Contractor Contractor ID Type of Contract Value Principal Site of Procurement Number of Number of Procurement (YYYY-MM-DD) Contract Contract Method Tenders/ Tenders/ Committee Performance Quotes Quotes Approval? Requested Received 2009-04-01 Emergency Works Supreme ConstructionSU-395/10- W $1,383,450.00 Grandy Hole - SS 1 1 Y 08/3-3 Golden Valley, Tom's River - Broadgate, Broadgate - Agualta Vale 1 2009-04-01 Emergency Works Supreme ConstructionSU-395/10- W $2,336,000.00 Fort George - SS 1 1 Y 08/3-3 Camberwell, Fort George - Cumsee, Fort George - Baxter's Mountain, Broadgate - Agualta Vale, Tom's River - Broadgate 2 2009-04-01 Multifunction Copier Copiers and G $473,000.00 National Works LT 3 3 Y Consumables Agency, 140 Maxfield Avenue 3 -

1 Environmental and Social Review Summary Jamaica Water Supply

Environmental and Social Review Summary Jamaica Water Supply Improvement Project This Environmental and Social Review Summary (ESRS) is prepared by MIGA staff and disclosed in advance of the MIGA Board consideration of the proposed issuance of a Contract of Guarantee. Its purpose is to enhance the transparency of MIGA’s activities. This document should not be construed as presuming the outcome of the decision by the MIGA Board of Directors. Board dates are estimates only. Any documentation which is attached to this ESRS has been prepared by the project sponsor, and authorization has been given for public release. MIGA has reviewed the attached documentation as provided by the applicant, and considers it of adequate quality to be released to the public, but does not endorse the content. Country: Jamaica Sector: Infrastructure Project Enterprise(s): The Bank of Nova Scotia Jamaica Limited and the National Water Commission of Jamaica; Vinci Construction Grands Projets (VCGP); BNP Paribas Environmental Category: B Date ESRS Disclosed: October 20, 2009 Status: Due Diligence A. Project Description The Jamaica Water Supply Improvement Project (JWSIP) entails a US$198.5 million refurbishment and expansion program aimed at addressing the perennial water supply constraints affecting the greater Kingston Metropolitan, Ocho Rios, and broader rural parish areas of Jamaica. It is being sponsored and implemented by the National Water Commission (NWC) of Jamaica, a state owned enterprise created under the 1980 National Water Commission Act, and overseen by the Jamaica Ministry of Housing and Water. To facilitate the JWSIP financing, the NWC has segmented the works into two categories (“A” & “B”), which will be implemented concurrently, using the same Engineering Procurement and Construction (EPC) Contractor, Vinci Construction Grands Projets (VCGP) of France, but financed by separate entities. -

DRM Enforcement Measures Order 2021

JAN. 15, 2021] PROCLAMATIONS, RULES AND REGULATIONS 1 THE JAMAICA GAZETTE SUPPLEMENT PROCLAMATIONS, RULES AND REGULATIONS 1 Vol. CXLIV FRIDAY, JANUARY 15, 2021 No. 1 No. 1 THE DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT ACT THE DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT (ENFORCEMENT MEASURES) ORDER, 2021 WHEREAS the Minister responsible for disaster preparedness and emergency management has given written notice to the Prime Minister that Jamaica appears to be threatened with or affected by the SARS–CoV-2 (Coronavirus COVID-19), and that measures apart from or in addition to those specifically provided for in the Disaster Risk Management Act should be taken promptly: AND WHEREAS on March 13, 2020, the Prime Minister by Order declared the whole of Jamaica to be a disaster area: NOW THEREFORE: In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Prime Minister by section 26(2) of the Disaster Risk Management Act, the following Order is hereby made:— Citation. 1. This Order may be cited as the Disaster Risk Management (Enforcement Measures) Order, 2021, and shall take effect on the 15th day of January, 2021. 2 PROCLAMATIONS, RULES AND REGULATIONS [JAN. 15, 2021 Enforcement. 2. The measures set out in this Order are directed to be enforced,in accordance with sections 26(5) to (7) and 52 of the Act, for removing or otherwise guarding against or mitigating the threat, or effects, of the SARS – CoV-2 (Coronavirus COVID-19) and the possible consequences thereof. Requirements 3.—(1) A person who, during the period January 15, 2021, to April 15, for entry to 2021, seeks to enter Jamaica, shall— Jamaica. (a) if the person is ordinarily resident in Jamaica, complete,through the website https://jamcovid19.moh.gov.jm/, the relevant application for entry; or (b) if the person is not ordinarily resident in Jamaica, (i) complete, through the website https:// www.visitjamaica.com, the relevant application for entry; and (ii) comply with all applicable provisions of the Immigration Restriction (Commonwealth Citizens) Act and the Aliens Act. -

Annual Report 2005-2006.Qxd

Notes Our Vision... The National Works Agency will create a world class safe, quality main road network meeting the needs of our clients in the towns, community and districts where they vacation, work and live. Our Mission... To plan, build and maintain a reliable, safe, and efficient main road network and flood control system which: Protects life and property Supports the movement of people, goods and services. Reduce the cost of transportation Promote economic growth and quality of life. Protects the environment. Our Values... We believe that our principal strength is our people and that our success will depend on our ability to provide them with the tools and the environment to allow them to excel. We demonstrate trust and respect for each other, our partners and stakeholders through open and honest communication. We respect the values, principles and opinions of the public as they help define our goals and evaluate our performance. We continuously strive for excellence, quality service, value for money, fiscal prudence, flexiblity, creativity and innovation. We commit to treating all persons with whom we come in contact fairly and without regards to their sex, race, religion, political affiliation or the community to which they belong. 2 National Works Agency- Annual Report 2005 -2006 National Works Agency- Annual Report 2005 -2006 71 Notes Contents Page PERSPECTIVES: Hon. Robert Pickersgill Minister, Housing, Transport, Water & Works 5 Hon. Dr. Fenton Ferguson State Minister in the Ministry of Housing, Transport,Water and Works 6 -

Guide Welcome Irie Isle

GUIDE WELCOME IRIE ISLE Seven Mile Beach Seven Mile Beach KNOWN FOR ITS STUNNING BEAUTY, Did you know? The traditional cooking technique FRIENDLY PEOPLE, LAND OF WOOD AND WATER known as jerk is said to have been invented by the island’s Maroons, VIBRANT CULTURE or runaway slaves. AND RICH HISTORY, Jamaica is a destination so dynamic and multifaceted you could visit hundreds of Negril, Frenchman’s Cove in Portland, Treasure Beach on the South Coast or the times and have a unique experience every single time. unique Dunn’s River Falls and Beach in Ocho Rios, there’s a beach for everyone. THERE’S NO BETTER Home of the legendary Bob Marley, arguably reggae’s most iconic and globally But if lounging on the sand all day is not your style, a visit to Jamaica may be recognised face, the island’s most popular musical export is an eclectic mix of just what the doctor ordered. With hundreds of fitness facilities and countless WORD TO DESCRIBE infectious beats and enchanting — and sometimes scathing — lyrics that can be running and exercise groups, the global thrust towards health and wellness has THE JAMAICAN heard throughout the island. The music is also celebrated through annual festivals spawned annual events such as the Reggae Marathon and the Kingston City such as Reggae Sumfest and Rebel Salute, where you could also indulge in Run. The get-fit movement has also influenced the creation of several health and EXPERIENCE Jamaica’s renowned culinary treats. wellness bars, as well as spa, fitness and yoga retreats at upscale resorts. -

Introduction

Environmental Impact Assessment Environmental Solutions Ltd. Executive Summary Introduction The Government of Jamaica through the National Water Commission (NWC) intends to effect improvements in the potable water supply for the Greater Spanish Town (GST) and Southeast St. Catherine (SESC) sections of the Kingston Metropolitan Area (KMA), with financial assistance from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC). These sections of the KMA are presently supplied by a number of sources within St. Catherine, including the Rio Cobre Scheme (constructed in the early 1970’s) and wells in Greater Spanish Town and Southeast St. Catherine. The current state of repair of all existing production and relift pumping facilities is poor while existing service storage reservoirs and tanks exhibit some deficiencies. Currently, about 95% of the population within Greater Spanish Town and SE St. Catherine has access to piped water but supply can be variable, with some NWC customers receiving water only for a few hours each day on occasion. Current “maximum month” water demand in Greater Spanish Town is estimated at some 63.5 Mega-Litres per day (Mld) or 13.98 migd and this is projected to rise to some 90.6 Mld (19.94 migd) in 2026 (the project design year). With current available supply of some 58.2 Mld (12.82 migd) there is a current deficit of some 5.3 Mld (1.82 migd). In the absence of the proposed capital works of the Project (but assuming some reduction of leakage as a result of ongoing in-house NWC initiatives) the deficit will rise by 2026 to some 32.4 Mld (7.12 migd). -

1 NATIONAL MONUMENTS CLARENDON Buildings Of

NATIONAL MONUMENTS CLARENDON Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest Halse Hall Great House (Declared 28/11/2002) Churches, Cemeteries, Tombs St. Peter’s Church, Alley (Declared 30/03/2000) Clock Towers May Pen Clock Tower (Declared 15/03/2001) Natural Sites Milk River Spa (Declared 13/09/1990) HANOVER Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest Barbican Estate (Declared 16/12/1993) Tamarind Lodge (Declared 15/07/1993) Old Hanover Gaol/Old Police Barracks, Lucea (Declared 19/03/1992) Tryall Great House and Ruins of Sugar Works (Declared 13/09/1990) Forts and Naval and Military Monuments Fort Charlotte, Lucea (Declared 19/03/1992) Historic Sites Blenheim – Birthplace of National Hero – The Rt. Excellent Sir Alexander Bustamante (Declared 05/11/1992) KINGSTON Buildings of Architectural and Historic Interest 40 Harbour Street (Declared 10/12/1998) Headquarters House, Duke Street (Declared 07/01/2000) Kingston Railway Station, Barry Street (Declared 04/03/2003) The Admiralty Houses, Port Royal (Declared 05/11/1992) Churches, Cemeteries, Tombs Coke Methodist Church, East Parade (Declared 07/01/2000) East Queen Street Baptist Church, East Queen Street (Declared 29/10/2009) Holy Trinity Cathedral, North Street (Declared 07/01/2000) Kingston Parish Church, South Parade (Declared 04/03/2003) Wesley Methodist Church, Tower Street (Declared 10/12/1998) Old Jewish Cemetery, Hunts Bay (Declared 15/07/1993) 1 Forts and Naval and Military Monuments Fort Charles, Port Royal (Declared 31/12/1992) Historic Sites Liberty Hall, 76 King Street (Declared 05/11/1992) Public Buildings Ward Theatre, North Parade (Declared 07/01/2000) Statues and Other Memorials Bust of General Antonio Maceo, National Heroes Park (Declared 07/01/2000) Cenotaph, National Heroes Park (Declared 07/01/2000) Negro Aroused, Ocean Boulevard (Declared 13/04/1995) Monument to Rt. -

Jamaica‟S Physical Features

Jamaica‟s Physical Features Objective: Describe Jamaica‟s physical features. Jamaica has physical features including: valleys, mountains, hills, rivers, waterfalls, plateau, caves, cays, mineral springs, harbours and plains. www.caribbeanexams.com Page 1 Valleys A valley is a low area that lies between two hills or mountains. A list of valleys in Jamaica is shown below. St. James Queen of Spain Valley Trelawny Queen of Spain Valley Hanover Great River Westmoreland Dean St. Catherine Luidas Vale St. Mary St Thomas in the Vale Portland Rio Grande St. Thomas Plantain Garden www.caribbeanexams.com Page 2 Mountains The mountains of the island can be broken up into three main groups. The first group is in the eastern section composed primarily of the Blue Mountain. This group also has the John Crow Mountains and is the most easterly mountain range in the island. They run from north-west to south-east in the parish of Portland and divide the Rio Grande valley from the east coast of the island. The second group or central region is formed chiefly of limestone, and extends from Stony Hill in St Andrew to the Cockpit country. The central range starts from Stony Hill and runs in a north westerly direction through Mammee Hill, Red Hills, Bog Walk, Guy's Hill, Mount Diablo and finally into the Cockpit country. The third group is the western section with Dolphin Head as its centre. www.caribbeanexams.com Page 3 Major Mountains www.caribbeanexams.com Page 4 Rivers Major Rivers in Jamaica www.caribbeanexams.com Page 5 Black River As the main mountain ranges in Jamaica run from west to east, the rivers, which start on their slopes, generally flow north or south.