Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Association Between the Lunar Cycle and Patterns

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN THE LUNAR CYCLE AND PATTERNS OF PATIENT PRESENTATION TO THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT. Grant Dudley Futcher Student number: 7709742 A research report submitted to the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Medicine in Emergency Medicine. Johannesburg, 2015 i DECLARATION I, Grant Dudley Futcher, declare that this research report is my own work. It is being submitted for the degree of Master of Science in Medicine (Emergency Medicine) in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at this or any other University. Signed on 25th day of August 2015 ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my children, Charis, Luke and Jarryd, who have patiently endured their father’s choice of medical discipline. iii PUBLICATIONS ARISING FROM THIS STUDY Nil iv ABSTRACT Aim: To determine any association between the lunar synodic or anomalistic months and the nature and volume of emergency department patient consultations and hospital admissions from the emergency department (ED). Design: A retrospective, descriptive study. Setting: All South African EDs of a private hospital group. Patients: All patients consulted from 01 January 2005 to 31 December 2010. Methods: Data was extracted from monthly records and statistically evaluated, controlling for calendric variables. Lunar variables were modelled with volumes of differing priority of hospital admissions and consultation categories including; trauma, medical, paediatric, work injuries, obstetrics and gynaecology, intentional self harm, sexual assault, dog bites and total ED consultations. Main Results: No significant differences were found in all anomalistic and most synodic models with the consultation categories. -

A Graduate Project Submitted in Partial Satisfaction for the Degree of Master of Arts in Educational Psychology, Counseling and Guidance

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NJRTHRIIX:;E THE EFFECT OF LUNAR PERIODICI1Y ON HUMAN BEHAVIOR A graduate project submitted in partial satisfaction for the degree of Master of Arts in Educational Psychology, Counseling and Guidance by Janis Cash Graham May, 1984 The Gragua~roject of Janis Cash Graham is approved: Dr. Robert Docter Dr. Bernard NisenhOlZ Dr. Stan y Charnofsky ( ainnan) California State University, Northridge ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT . • • • • ~ • • . • . • ~ . • • • • . • • . • • . • v Chapter 1 INIRODUCTION 1 Purpose of the Project . • . 5 Limitations of the Project 6 Chapter 2 HISIDRY 8 Religion •.•...... 8 Folklore and Superstition. 14 Lycanthropy .......• 19 Chapter 3 IN SEARCH OF 'IHE ''LUNAR EFFECT'': PRESENT DAY INVESTIGATIONS • • • • 30 The Phases of the Moon 32 Case Studies • • . 34 Studies on Marine Life . 36 Biological Rhythms . 39 Medical Studies ..... 41 Studies of Human Behavior .. 44 The \IJork of Lieber and Sherin. 48 Chapter 4 MCDN AND MAN: 'IHEORIES . • . • 52 The Light of the moon. 52 The Geophysical Environment. 55 The Biological Tides Theory. 60 Other Theories of Man and the Moon 66 Chapter 5 APPLICATION AND St.M1ARY 71 Application to Research and Clinical Psychology. 71 Conceptual Application . 76 S'llii.llilary . • . • . • . 83 iii ~-' ' Page REFERENCES. 89 APPENDICES A DEFINITION OF TERMS 93 B ''A PERS01':W... NOTE'' • • 97 iv ABS'IRACT 'lliE EFFECT OF LUNAR PERIODICITY ON HUMAN BEHAVIOR by Janis Cash Graham Master of Arts in Educational Psychology Counseling and Guidance The belief in the power of the moon to influence life on our planet has existed from earliest recorded history, and plays an important role in the history of religion, folklore, and superstition. -

The Overall Density of Total Seabirds in the Surveyed Shore-Watch Area (E

RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MARINE MAMMAL AND SEABIRD POPULATIONS IN SOUTH- WESTERN IRISH WATERS (R.A.M.S.S.I.) Daphne Roycroft, Michelle Cronin, Mick Mackey, Simon N. Ingram Oliver O’Cadhla Coastal and Marine Resources Centre, University College Cork March 2007 HEA Higher Education Authority An tÚdarás um Ard-Oideachas CONTENTS i) Summary ii) Acknowledgements General Introduction Seabirds and marine mammals in southwest Ireland 2 Rationale for RAMSSI 6 Study sites 7 Inshore risks to seabirds and marine mammals 11 i. Surface pollution 11 ii. Ballast water 13 iii. Organochlorine pollution and antifoulants 14 iv. Disease 15 v. Acoustic pollution 15 vi. Disturbance from vessels 16 vii. Wind farming 17 viii. Mariculture 17 ix. Fisheries 19 Aims and Objective 22 References 23 Appendix 33 Chapter 1. Seabird distribution and habitat-use in Bantry Bay 1.1 Abstract 35 1.2 Introduction 35 1.3 Study site 37 1.4 Methods 37 1.4.1 Line transect techniques 37 1.4.2 Data preparation 40 1.4.3 Data analysis 45 1.5 Results 46 1.5.1 Modelling 46 1.5.2 Relative abundance 54 1.6 Discussion 59 1.7 References 66 1.8 Appendix 70 Chapter 2. Shore-based observations of seabirds in southwest Ireland 2.1 Abstract 72 2.2 Introduction 73 2.3 Methods 74 2.3.1 Shore-watch techniques 74 2.3.2 Analysis of relative abundance 75 2.3.3 Density calculation 77 2.3.4 Comparison of shore and boat-based densities 79 2.4 Results 80 2.4.1 Relative abundance 80 2.4.2 Density 87 2.5 Discussion 89 2.6 References 93 Chapter 3. -

Evaluation of Antecedent Ambiguity on Identification and Categorization of Behavior in Lunar-Effects Research

Modern Psychological Studies Volume 25 Number 1 Article 8 January 2020 Evaluation of Antecedent Ambiguity on Identification and Categorization of Behavior in Lunar-Effects Research Brenda M. Gabbert University of Alaska Anchorage, [email protected] Mychal A. Machado University of Alaska Anchorage, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Gabbert, Brenda M. and Machado, Mychal A. (2020) "Evaluation of Antecedent Ambiguity on Identification and Categorization of Behavior in Lunar-Effects Research," Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 25 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol25/iss1/8 This articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Magazines, and Newsletters at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Psychological Studies by an authorized editor of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTIFICATION AND CATEGORIZATION OF BEHAVIOR 1 Abstract We created an online survey to determine the degree to which 114 participants could correctly identify and categorize scripted visual examples of typical and atypical behavior when the antecedent preceding those behaviors was not present. We also asked participants to determine whether our visual examples of behavior occurred in the presence of a full moon, and subsequently evaluated these data in the context of participant’s self-reported belief in lunar- effects. Our results show the absence of an antecedent event influenced some participants’ identification and categorization accuracy scores, and that participants with a prior belief in lunar effects were more likely to attribute atypical behavior to the presence of a full moon. -

Misbeliefs – Acquisition & Probable Examples

HUMINANITY Series of PowerPoint Presentations by J. W. Gardner ● Misbeliefs – Acquisition & Probable Examples ● Big Picture Science – Observable Universe ● Big Picture Science – Planet Earth ● Big Picture Science – Life on Earth ● Basic Science Sampler – Quantum Physics, Relativity and Thermodynamics Contents Introduction Misbelief Acquisition – 4 I's Ignorance Insecurity Intuition Indoctrination Empirical Truths Scientific Consensus Historical Knowledge Benefits of Modern Medicine Popularity of Liberal Democracy Reliability of Modern Technology Probable Misbeliefs Resources Pseudohistory Pseudoscience Paranormal Belief Surveys Wrap-up Shortcuts to topics underlined Quotes Contents Introduction Misbelief Acquisition – 4 I's Ignorance Insecurity Intuition Indoctrination Empirical Truths Scientific Consensus Historical Knowledge Benefits of Modern Medicine Popularity of Liberal Democracy Reliability of Modern Technology Probable Misbeliefs Resources Pseudohistory Pseudoscience Paranormal Belief Surveys Wrap-up Quotes Introduction Humans are the only beings known to provide explanations for their existence. Simple accounts might date back to the first behaviorally modern humans (400 centuries or so ago) Prior to modern science most explanations involved supernatural causes Although a fairly deep scientific understanding of the world was achieved in the 20th century, most humans have yet to fully embrace it, either for lack awareness or a penchant for traditional accounts Unfortunately, a world overpopulated by a technologically advanced -

The Lunar Cycle: Effects on Human and Animal Behavior and Physiology

Postepy Hig Med Dosw. (online), 2006; 60: 1-7 www.phmd.pl e-ISSN 1732-2693 Review Received: 2005.06.09 Accepted: 2005.06.27 The lunar cycle: effects on human and animal behavior Published: 2006.01.06 and physiology Cykl księżycowy: wpływ na zachowanie ludzi i zwierząt i ich fi zjologię Michał Zimecki Department of Experimental Therapy, The Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wrocław, Poland Summary Human and animal physiology are subject to seasonal, lunar, and circadian rhythms. Although the seasonal and circadian rhythms have been fairly well described, little is known about the effects of the lunar cycle on the behavior and physiology of humans and animals. The lunar cycle has an impact on human reproduction, in particular fertility, menstruation, and birth rate. Melatonin le- vels appear to correlate with the menstrual cycle. Admittance to hospitals and emergency units because of various causes (cardiovascular and acute coronary events, variceal hemorrhage, diar- rhea, urinary retention) correlated with moon phases. In addition, other events associated with human behavior, such as traffi c accidents, crimes, and suicides, appeared to be infl uenced by the lunar cycle. However, a number of reports fi nd no correlation between the lunar cycle and human reproduction and admittance to clinics and emergency units. Animal studies revealed that the lunar cycle may affect hormonal changes early in phylogenesis (insects). In fi sh the lunar clock infl uences reproduction and involves the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis. In birds, the da- ily variations in melatonin and corticosterone disappear during full-moon days. The lunar cycle also exerts effects on laboratory rats with regard to taste sensitivity and the ultrastructure of pi- neal gland cells. -

Redalyc.Moon Cycle Effects on Humans: Myth Or Reality?

Salud Mental ISSN: 0185-3325 [email protected] Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz México Muñoz, Jairo; Santillán, Ana María; Mondragón, Ricardo; Erkert, Hans G. Moon cycle effects on humans: myth or reality? Salud Mental, vol. 23, núm. 6, diciembre, 2000, pp. 33-39 Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=58262305 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative ACTUALIZACION POR TEMAS Moon cycle effects on humans: myth or reality? Jairo Muñoz-Delgado* Ana María Santillán-Doherty* Ricardo Mondragón-Ceballos* Hans G. Erkert** Figura 1. Celestial Pap, Remedios Varo (1908-1963), Private Collection, Mexico City. Summary which can be most suitably explained by chronobiology, given For centuries, it has been of popular belief that the moon cycle that the organisms behavioral patterns are the result of the influences human physiology and behavior. This is an idea interaction between their endogenous temporal programs which are the cause of biological rhythms and their tuning to * Departamento de Etología, Psicobiología y Conducta, Subdirección external stimuli, both environmental and social. However, non- de Neurociencias, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente, natural effects, such as city noise and electric light, among México, D.F. others, may mask such interactions. Research on this subject ** Zoologisches Institut, Fakultät für Biologie, Universität Tübingen, has looked for the causal relation between moon cycles and Germany. -

PASI Tide Lecture

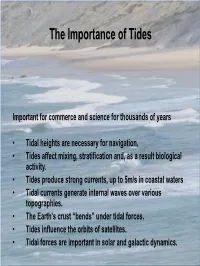

The Importance of Tides Important for commerce and science for thousands of years • Tidal heights are necessary for navigation. • Tides affect mixing, stratification and, as a result biological activity. • Tides produce strong currents, up to 5m/s in coastal waters • Tidal currents generate internal waves over various topographies. • The Earth's crust “bends” under tidal forces. • Tides influence the orbits of satellites. • Tidal forces are important in solar and galactic dynamics. The Nature of Tides “The truth is, the word "tide" as used by sailors at sea means horizontal motion of the water; but when used by landsmen or sailors in port, it means vertical motion of the water.” “One of the most interesting points of tidal theory is the determination of the currents by which the rise and fall is produced, and so far the sailor's idea of what is most noteworthy as to tidal motion is correct: because before there can be a rise and fall of the water anywhere it must come from some other place, and the water cannot pass from place to place without moving horizontally, or nearly horizontally, through a great distance. Thus the primary phenomenon of the tides is after all the tidal current; …” The Tides, Sir William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) – 1882, Evening Lecture To The British Association TIDAL HYDRODYNAMICS AND MODELING Dr. Cheryl Ann Blain Naval Research Laboratory Stennis Space Center, MS, USA [email protected] Pan-American Studies Institute, PASI Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, 2–13 January, 2013 — Valparaíso, Chile -

Another Lunar Effect Put to Rest

Another Lunar Effect Put to Rest Thirty years ago, published reports suggested that plants could grow better on lunar "soil" than they could on terrestrial soils. A series of experimental errors, reporting errors, and omissions led to this conclusion. Previously unpublished data easily explain the reported effects. HAVEN SWEET his article is long overdue. It has been written in my mind hundreds of times, only to be displaced by Tmore pressing activities. I eventually convinced myself that people had forgotten the claims made after man first landed on the Moon, claims that attributed very unusual properties to the Moon. My complacency changed while listening to one of the many twenty-fifth anniversary tributes to the first lunar landing. (Now the thirtieth anniversary has passed, in July 1999, and I can wait no longer.) I heard a former NASA offi- cial refer to the quarantine testing and indicate that there was one significant result: that plants had been shown to grow better on Moon dust than they did on Earth soil. SKEPTICAL INQUIRER November/December 1999 47 This statement thrust me back to my days with the space look at how these results came to be, and how the myth grew. program, a time when similar statements were made with lit- tle regard for the facts. At that time, the press was hungry for Background of Plant Quarantine Testing news. The excitement of the lunar landing still held the pub- As part of the trip to the Moon, NASA was required to deter- lic interest in everything dealing with space. T h e spotlight was mine if "lunar organisms" existed, and if so, whether they on NASA, and some used this opportunity to present specula- posed a threat to Earth. -

Sa.*54& Research Committee Chair

THE EFFECT OF LUNAR PHASE ON STUDENT BEHAVIOR Anthony S. Johnson A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree In School Guidance and Counseling K-12 Approved: 6 Semester Credits &~~sa.*54& Research Committee Chair Research Committee Members The Graduate School University of Wisconsin-Stout May, 2005 The Graduate School University of Wisconsin Stout Menomonie, WI 5475 1 ABSTRACT Johnson Anthony S. (Writer) (Last Name) (First Name) (Middle Initial) The Effect of Lunar Phase on Student Behavior (Title) School Guidance and Counseling Dr. Denise Brouillard 512005 60 (Graduate Program) (Research Advisor) (Month/Year) (# of Pages) American Psychological Association (APA), 5thedition (Name of Style Manual Used in this Study) Lunatic and lunacy are words commonly used to describe an unusual person or their aberrant behavior. These terms suggest that the abnormality is in some way connected with the moon, as the words are derived from the Latin root Luna which translates to moon. Throughout human history there have existed tales and lore regarding this purported lunar influence on the human species as well as much of the natural world iii including flora and fauna. Some of these beliefs have persisted to the present day. Many of these notions center on the phases of the moon, especially the full moon. One belief held by some in the teaching profession, whether sincerely or in jest, is that student behavior is noticeably different on or around the day on which a full moon occurs. In teacher terms the students are generally described as "acting up" or "squirrelly," though the specific meaning of that phrase is open to wide interpretation. -

Moon Phase As the Irrationality

51 MOON PHASE AS THE CAUSE OF MONDAY IRRATIONALITY: CASE OF ASEAN DAY OF THE WEEK ANOMALY RAYENDA KHRESNA BRAHMANA Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia CHEE -WOOI HOOY Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang , Malaysia ZAMRI AHMAD Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang , Malaysia Received: August 28, 2013 Accepted: January 22, 2014 Online Published: February 5, 2014 Abstract Many Day-of-the week anomaly papers have suggested investor behaviour as the explanation of highly differentiated returns on Mondays; yet, rarely found a paper has empirically investigated it. Therefore, this paper proposes Moon -Induced mood as the determinant of that irrational behaviour. This proposition is based on our preliminary findings that the full moon phase occurred more often on Mondays compared to other days; an indication of a causal relationship. By taking Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines as samples during the period of 1999-2010, thi s paper found : (1) There is evidence of a Monday effect across all the ASEAN stock markets, (2) The moon phase and its interaction with Mondays has significantly influenced the Monday effect, and (3) A full moon on Monday has significant negative influenc ed on Monday returns. In conclusion, the stimulation by moon phase forms affection bias, and the resulting outcome is the irrational stock market behavior. Keywords : Moon Effect, Day -Of-Week-Anomaly, Irrational Behavior, ASEAN 1. Introduction The belief that phases of the moon affect behavior dates back to ancient times. However, the debate about lunar effect on the human body and mind has been a hugely argued anecdotally as well as empirically in literature. For instance is Campbell (1983) who asserts that lunar lunacy research is not scientifically encouraging and explaining human behavior. -

The Lunar Effect

An Ayurvedic Perspective on The Lunar Effect By : Arlini Singh ya esa sodasa-kalah puroso bhagavan manomayo ‘nnamayo “mrtamayo deva-pitr-manusya-bhuta-pasu-paksi-sarispa- virudham pranapy ayana-silavat sarvamaya iti varnayanti Translation Because the moon is full of all potentialities, it represents the influence of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. The moon is the predominating deity of everyone’s mind, and therefore the moon-god is called Manomaya. He is also called Annamaya because he gives potency to all herbs and plants, and he is called Amrtamaya because he is the source of life for all living entities. The moon pleases the demigods, inhabitants of Pitrloka, animals, birds, reptiles, trees, plants and all other living entities. Everyone is satisfied by the presence of the moon. Therefore the moon is also called Sarvamaya ( all pervading) ( Srimad - Bhagavatam 5.22.10)1. Introduction For centuries, Man has looked up and gazed at the wonder and splendour of the Moon. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Moon has played such a vital role in the traditions of every culture, as Man has appreciated and respected the Moon, not only for it’s beauty, but also for his survival. Johanna Paungger and Thomas Poppe in their book, Guided by the Moon, states that Man discovered: “ - that numerous natural phenomena - the tides, birth, meteorological events, women’s menstrual cycle, and much more - are related to the movements of the moon - that the behaviour of many animals depends on the position of the moon; that birds, for example, always