Verb-Tenses-Handout-NEW-MAY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interpretation of Tense — I Didn't Turn Off the Stove Toshiyuki Ogihara

The interpretation of tense — I didn’t turn off the stove Toshiyuki Ogihara — University of Washington [email protected] Kiyomi Kusumoto — Kwansei Gakuin University [email protected] Abstract This chapter examines Partee’s (1973) celeBrated claim that tenses are not existential quantifiers but pronouns. In the first half of the chapter, we show that this proposal successfully accounts for the Behavior of tense morphemes regarding deixis, anaphora, and presupposition. It is also compatiBle with cases where tense morphemes Behave like Bound variables. In the second half of the chapter, we turn to the syntax-semantics interface and propose some concrete implementations Based on three different assumptions aBout the semantics of tense: (i) quantificational; (ii) pronominal; (iii) relational. Finally, we touch on some tense-related issues involving temporal adverBials and cross-linguistic differences. Keywords tense, pronoun, quantification, Bound variaBle, referential, presupposition, temporal adverbial (7 key words) 1. Introduction This article discusses the question of whether the past tense morpheme is analogous to pronouns and if so how tense is encoded in the system of the interfaces between syntax and semantics. The languages we will deal with in this article have tense morphemes that are attached to verbs. We use 1 this type of language as our guide and model. Whether tense is part of natural language universals, at least in the area of semantic interpretation, is debatable.1 Montague’s PTQ (1973) introduces a formal semantic system that incorporates some tense and aspect forms in natural language and their model-theoretic interpretation. It introduces tense operators based on Prior’s (1957, 1967) work on tense logic. -

Perfect Tenses 8.Pdf

Name Date Lesson 7 Perfect Tenses Teaching The present perfect tense shows an action or condition that began in the past and continues into the present. Present Perfect Dan has called every day this week. The past perfect tense shows an action or condition in the past that came before another action or condition in the past. Past Perfect Dan had called before Ellen arrived. The future perfect tense shows an action or condition in the future that will occur before another action or condition in the future. Future Perfect Dan will have called before Ellen arrives. To form the present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect tenses, add has, have, had, or will have to the past participle. Tense Singular Plural Present Perfect I have called we have called has or have + past participle you have called you have called he, she, it has called they have called Past Perfect I had called we had called had + past participle you had called you had called he, she, it had called they had called CHAPTER 4 Future Perfect I will have called we will have called will + have + past participle you will have called you will have called he, she, it will have called they will have called Recognizing the Perfect Tenses Underline the verb in each sentence. On the blank, write the tense of the verb. 1. The film house has not developed the pictures yet. _______________________ 2. Fred will have left before Erin’s arrival. _______________________ 3. Florence has been a vary gracious hostess. _______________________ 4. Andi had lost her transfer by the end of the bus ride. -

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

Choosing a Verb Tense the Present Tense Add –S to Make the Third Person Singular Present Tense

Choosing a Verb Tense The Present Tense Add –s to make the third person singular present tense. Since most academic, scientific, and technical writing is done in present tense, this is a very important reminder! The system permits Each operator controls Use the present tense --to show present states or conditions: The test program is ready. The bell sounds shrill. --to show natural laws or eternal truths: The earth rotates around the sun. Carbon and oxygen combine to form carbon dioxide. --to show habitual actions and repeated acts: We hold a staff meeting every Tuesday. The new file boots the computer. --to quote from or paraphrase published work: Nagamichi claims that calcium inhibits the reaction. MCI’s brochure reads “We are more efficient than AT&T.” --to define or explain procedures or terminology: The board fits in the lower right-hand slot. BOC stands for “British Oxygen Corporation.” --to show possible futures in time and conditional clauses: Your supervisor will recommend you for promotion if she likes your work. The minutes of the meeting will be circulated once I type them. The Past Tense Add the proper suffix (usually –ed) or infix to the verb stem to make the past tense. Consult a dictionary if you have questions about the correct past form. Use the past tense --for events that happened at a specific time in the past: The fax arrived at 4:59 PM. Kennedy died in 1963. --for repeated or habitual items which no longer happen: We used to have our department meetings on Tuesday. He smoked cigarettes constantly until his coronary. -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

On Four Differences Between Two Metaphorical Expressions of Future

63 佐渡一邦 On Four Differences between Two Metaphorical Expressions of Future Kazukuni SADO* Abstract The aim of this paper is to clarify the differences between two types of expressions whose forms are in the present, but express a future event. The simple present and present in present are compared with regard to four perspectives: modality, human endeavor, present relevance, and proximity to the present. We may conclude from research that the simple present allows only modalization, is neutral to human endeavor, has much stronger relevance to the present moment and is neutral to the distance from the time of utterance, while the present in present allows both types of modality, expresses the results of human endeavor and although is less related to the present moment, is likely to describe the near future. 0. Introduction Most of us would accept that verb tenses in the English language are far from simple. The expression of a future event, for example, is not necessarily expressed in the future tense. The use of the present tense to express the future is well explained as “futurate” in Huddleston and Pullum (2002) and elaborated further in Sado (2016). However, we are of the view that English has a future tense and thus, it seems no longer appropriate to use the term, ”futurate” in our discussion as Sado (2016) did. Sado (2017:60) replaced the term with “present of futurity” to refer to all present tense forms that are employed to express events in the future. This discrepancy between form and meaning is explained by Huddleston and Pullum (2002) in terms of knowledge in the present like schedules of public transportation as thus illustrated in the example below from Kreidler (2014:111). -

The Formation, Translation and Use of Participles in Latin, and the Nature of Relative Time

Chapter 23: Participles Chapter 23 covers the following: the formation, translation and use of participles in Latin, and the nature of relative time. At the end of the lesson we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There are four important rules to remember in Chapter 23: (1) Latin has four participles: the present active, the future active; the perfect passive and the future passive. It lacks, however, a present passive participle (“being [verb]-ed”) and a perfect active participle (“having [verb]-ed”). (2) The perfect passive, future active and future passive participles belong to first/second declension. The present active participle belongs to third declension. (3) The verb esse has only a future active participle (futurus). It lacks both the present active and all passive participles. (4) Participles show relative time. What are participles? At heart, participles are verbs which have been turned into adjectives. Thus, technically participles are “verbal adjectives.” The first part of the word (parti-) means “part;” the second part (-cip-) means “take,” indicating that participles “partake, share” in the characteristics of both verbs and adjectives. In other words, the base of a participle is verbal, giving it some of the qualities of a verb, for instance, tense: it can indicate when the action is happening (now or then or later; i.e. present, past or future); conjugation: what thematic vowel will be used (e.g. -a- in first conjugation, -e- in second, and so on); voice: whether the word it’s attached to is acting or being acted upon (i.e. -

Narrative Genres Narrative Text 1

Moorgate Primary School English: INTENT Grammar, Punctuation and Writing Genres Criteria for Fiction and Non-Fiction Genres This is a suggested overview for each genre, giving a list of grammar and punctuation. It is not a definitive list. It will depend on the age group as to what you will include or exclude. For each genre you will work on vocabulary such as prefixes, suffixes, antonyms, synonyms, homonyms, etc. Where possible, different sentence structures should be taught. This will be developed through the year and throughout the Key Stage. Narrative Genres Narrative text 1. Adventure and mystery stories – past tense First or third person 2. Myths and legends – past tense Inverted commas 3. Stories with historical settings – past tense Personification 4. Stories set in imaginary worlds – past or future tense Similes 5. Stories with issues and dilemmas – past tense Metaphors 6. Flashback – past and present tense Onomatopoeia 7. Traditional fairy story – past tense Noun phrases 8. Ghost story – past tense Different sentence openers (prepositions, adverbs, connectives, “- ing” words, adverbs, “-ed” words, similes) Synonyms Antonyms Specific nouns (proper) Semicolons to separate two sentences Colons to separate two sentences of equal weighting Informal and formal language Lists of three – adjectives and actions Indefinite pronouns Emotive language Non-Fiction Genres Explanation text Recount text Persuasive text Report text Play scripts Poetry text Discussion text Present tense (This includes genres Present tense Formal language Exclamation -

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> in ROMANCE and ENGLISH

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diego A. de Acosta May 2006 © 2006 Diego A. de Acosta <HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY Diego A. de Acosta, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 Synopsis: At first glance, the development of the Romance and Germanic have- perfects would seem to be well understood. The surface form of the source syntagma is uncontroversial and there is an abundant, inveterate literature that analyzes the emergence of have as an auxiliary. The “endpoints” of the development may be superficially described as follows (for English): (1) OE Ic hine ofslægenne hæbbe > Eng I have slain him The traditional view is that the source syntagma, <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle>, is structured [have [noun participle]], and that this syntagma undergoes change as have loses its possessive meaning. In this dissertation, I demonstrate that the traditional view is untenable and readdress two fundamental questions about the development of have-perfects: (i) how is the early ability of have to predicate possession connected with its later role in the perfect?; (ii) what are the syntactic structures and meanings of <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> before the emergence of the have-perfect? With corpus evidence, I show that that the surface string <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> corresponds to three different structures in Old English and Latin; all of these survive into modern English and the Romance languages. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

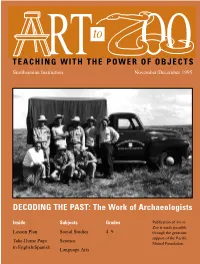

DECODING the PAST: the Work of Archaeologists

to TEACHINGRT WITH THE POWER OOOF OBJECTS Smithsonian Institution November/December 1995 DECODING THE PAST: The Work of Archaeologists Inside Subjects Grades Publication of Art to Zoo is made possible Lesson Plan Social Studies 4–9 through the generous support of the Pacific Take-Home Page Science Mutual Foundation. in English/Spanish Language Arts CONTENTS Introduction page 3 Lesson Plan Step 1 page 6 Worksheet 1 page 7 Lesson Plan Step 2 page 8 Worksheet 2 page 9 Lesson Plan Step 3 page 10 Take-Home Page page 11 Take-Home Page in Spanish page 13 Resources page 15 Art to Zoo’s purpose is to help teachers bring into their classrooms the educational power of museums and other community resources. Art to Zoo draws on the Smithsonian’s hundreds of exhibitions and programs—from art, history, and science to aviation and folklife—to create classroom- ready materials for grades four through nine. Each of the four annual issues explores a single topic through an interdisciplinary, multicultural Above photo: The layering of the soil can tell archaeologists much about the past. (Big Bend Reservoir, South Dakota) approach. The Smithsonian invites teachers to duplicate Cover photo: Smithsonian Institution archaeologists take a Art to Zoo materials for educational use. break during the River Basin Survey project, circa 1950. DECODING THE PAST: The Work of Archaeologists Whether you’re ten or one hundred years old, you have a sense of the past—the human perception of the passage of time, as recent as an hour ago or as far back as a decade ago. -

Grammar Workshop Verb Tenses

Grammar Workshop Verb Tenses* JOSEPHINE BOYLE WILLEM OPPERMAN ACADEMIC SUPPORT AND ACCESS CENTER AMERICAN UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 29, 2 0 1 6 *Sources consulted: Purdue OWL and Grammarly Handbook What is a Verb? Every basic sentence in the English language must have a noun and a verb. Verbs are action words. Verbs describe what the subject of the sentence is doing. Verbs can describe physical actions like movement, less concrete actions like thinking and feeling, and a state of being, as explained by the verb to be. What is a Verb? There are two specific uses for verbs: Put a motionless noun into motion, or to change its motion. If you can do it, its an action verb. (walk, run, study, learn) Link the subject of the sentence to something which describes the subject. If you can’t do it, it’s probably a linking verb. (am, is) Action Verbs: Susie ran a mile around the track. “Ran” gets Susie moving around the track. Bob went to the book store. “Went” gets Bob moving out the door and doing the shopping at the bookstore. Linking Verbs: I am bored. It’s difficult to “am,” so this is likely a linking verb. It’s connecting the subject “I” to the state of being bored. Verb Tenses Verb tenses are a way for the writer to express time in the English language. There are nine basic verb tenses: Simple Present: They talk Present Continuous: They are talking Present Perfect: They have talked Simple Past: They talked Past Continuous: They were talking Past Perfect: They had talked Future: They will talk Future Continuous: They will be talking Future Perfect: They will have talked Simple Present Tense Simple Present: Used to describe a general state or action that is repeated.