Contemporary American Novelists (1900-1920) by Carl Van Doren</H1>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania, and the First Nations: The Treaties of 1736–62. Edited by SUSAN KALTER. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006. xiv, 453 pp. Illustrations, notes, glossary, index. $45.) Between 1736 and 1762, Benjamin Franklin published thirteen treaties made between Pennsylvania and the Six Nations Iroquois and their native allies, including the Lenapes and the Shawnees. At these treaty negotiations, leaders from different cultures gathered to determine vital issues of war and peace, regulate intercultural exchange, and seek justice from one another. William Penn’s secretary, James Logan, noted that the 1736 treaty talks in Philadelphia were conducted “in the presence and hearing of some Thousands of our People” (p. 56). Treaty negotiations were public spectacles in an age without many large- scale events. Of enormous importance in the eighteenth century, the treaties were largely forgotten in the nineteenth century, only to be rediscovered in the early twentieth century as a compelling and uniquely American literary form. In 1938, Julian P.Boyd republished the treaties in a single volume with an introduction by Carl Van Doren. According to Van Doren, the “stately folios” printed by Franklin were “after two hundred years the most original and engaging documents of their century in America” (Indian Treaties Printed by Benjamin Franklin, vii). Boyd reproduced the treaties in facsimile on legal-sized paper, in a beautiful edition of five hundred numbered copies. These large, unwieldy, and expensive books have rested in the special collections of major research libraries, often with their pages uncut and unread. This new edition by Susan Kalter will make these important documents much more accessible and available. -

THE Iffilville REVIVAL a Study of Twentieth Century Criticism

THE iffiLVILLE REVIVAL A Study of Twentieth Century Criticism Through its Treatment of Herman Melville DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By BERNARD MICHAEL WOLPERT, B.S. in Ed., M.A. The Ohio State University 1951 Approved by; Adviser CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Backgrounds of Twentieth Century Criticism .......... 1 II. British Origins of the Melville R e v i v a l ............ 22 III. Melville and the Methods of Literary History......... 41 IV. Melville and Sociological Criticism.......... 69 V. Melville and Psychological Criticism.......... 114- VI, Melville and Philosophical Criticism ............. 160 VII. Melville and the New Criticism . ................ IS? VIII. Melville and the Development of Pluralistic Criticism 24-0 CHAPTER I Backgrounds of Twentieth Century Criticism At the time of Melville's death in I89I, the condition of literary criticism in America was amorphous. So dominant had become the demands of a journalism that catered to a flourishing middle-class public de termined to achieve an easy method to "culture," that the literary critic of this period, the eighties and nineties, devised an artificial tradition by which he could protect himself against the democratic so ciety with which he was acutely dissatisfied. This tradition was, therefore, conservative in nature. Its values, based on customary taste and training, were selected primarily as a refuge against both the con temporary American society -

Pulitzer Prizes

PULITZER PRIZES The University of Illinois The Pulitzer Prize honors those in journalism, letters, and HUGH F. HOUGH at Urbana-Champaign music for their outstanding contributions to American (1924- ) shared the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for Local General Spot News Reporting with fellow U of I alumnus Arthur M. Petacque has earned a reputation culture. The University of Illinois is well-represented for uncovering new evidence that led to the reopening of efforts of international stature. among the recipients of this prestigious award. to solve the 1966 murder case of Illinois Sen. Charles Percy’s Its distinguished faculty, daughter. Hough received a U of I Bachelor of Science in 1951. ALUMNI outstanding resources, The campus PAUL INGRASSIA breadth of academic BARRY BEARAK boasts two (1950- ) shared the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for Beat Reporting for (1949- ) received the 2002 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting programs and research coverage of management turmoil at General Motors Corp. He Nationalfor his Historic coverage of daily life in war-ravaged Afghanistan. Bearak disciplines, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree from the University in 1972. pursued graduate studies in journalism at the U of I and earned large, diverse student Landmarks:his Master the of Science in 1974. MONROE KARMIN body constitute an Astronomical (1929- ) shared the 1967 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting educational community MICHAEL COLGRASS for his part in exposing the connection between U.S. crime and (1932- ) won the 1978 Pulitzer Prize in Music for his piece, Deja Vu ideally suited for Observatory gambling in the Bahamas. Karmin received a U of I Bachelor of for Percussion Quartet and Orchestra, which was commissioned scholarship and Science in 1950. -

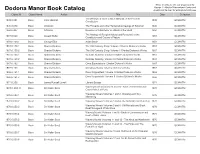

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography

THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY VOLUME CXXXVI October 2012 NO. 4 EDITORIAL Tamara Gaskell 329 INTRODUCTION Daniel P. Barr 331 REVIEW ESSAY:DID PENNSYLVANIA HAVE A MIDDLE GROUND? EXAMINING INDIAN-WHITE RELATIONS ON THE EIGHTEENTH- CENTURY PENNSYLVANIA FRONTIER Daniel P. Barr 337 THE CONOJOCULAR WAR:THE POLITICS OF COLONIAL COMPETITION, 1732–1737 Patrick Spero 365 “FAIR PLAY HAS ENTIRELY CEASED, AND LAW HAS TAKEN ITS PLACE”: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE SQUATTER REPUBLIC IN THE WEST BRANCH VALLEY OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, 1768–1800 Marcus Gallo 405 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS:A CUNNING MAN’S LEGACY:THE PAPERS OF SAMUEL WALLIS (1736–1798) David W. Maxey 435 HIDDEN GEMS THE MAP THAT REVEALS THE DECEPTION OF THE 1737 WALKING PURCHASE Steven C. Harper 457 CHARTING THE COLONIAL BACKCOUNTRY:JOSEPH SHIPPEN’S MAP OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER Katherine Faull 461 JOHN HARRIS,HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION, AND THE STANDING STONE MYSTERY REVEALED Linda A. Ries 466 REV.JOHN ELDER AND IDENTITY IN THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY Kevin Yeager 470 A FAILED PEACE:THE FRIENDLY ASSOCIATION AND THE PENNSYLVANIA BACKCOUNTRY DURING THE SEVEN YEARS’WAR Michael Goode 472 LETTERS TO FARMERS IN PENNSYLVANIA:JOHN DICKINSON WRITES TO THE PAXTON BOYS Jane E. Calvert 475 THE KITTANNING DESTROYED MEDAL Brandon C. Downing 478 PENNSYLVANIA’S WARRANTEE TOWNSHIP MAPS Pat Speth Sherman 482 JOSEPH PRIESTLEY HOUSE Patricia Likos Ricci 485 EZECHIEL SANGMEISTER’S WAY OF LIFE IN GREATER PENNSYLVANIA Elizabeth Lewis Pardoe 488 JOHN MCMILLAN’S JOURNAL:PRESBYTERIAN SACRAMENTAL OCCASIONS AND THE SECOND GREAT AWAKENING James L. Gorman 492 AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY LINGUISTIC BORDERLAND Sean P. -

Stories from an Oklahoman: George Milburn's Style and Satire Linda Dayton Carson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 Stories from an Oklahoman: George Milburn's style and satire Linda Dayton Carson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Carson, Linda Dayton, "Stories from an Oklahoman: George Milburn's style and satire " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7911. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7911 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stories from an Oklahomam George Milbum's style and satire i>y Linda Dayton Carson A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Departmenti English Major I English Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames* Iowa 1977 11 TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv INTRODUCTION 1 BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION 3 MILBURN AS A SOUTHWESTERN WRITER 9 WORKS xk The Hobo's Hombook and Related Studies 15 Oklahoma Town 18 Mencken and Magazines 23 No More Trumpets and Other Stories 28 Stories, 193^-1935 33 CataJ.ogue 3^ "The Road to Calamity" and Other Stories kO Flannigan' -

“Some Men Ride on Such Space”: Olson's Call Me

49th Parallel, Vol. 31 (Spring 2013) Tally ISSN: 1753-5794 (online) “Some men ride on such space”: Olson’s Call Me Ishmael, the Melville Revival, and the American Baroque Robert T. Tally Jr. * Texas State University Call Me Ishmael, Charles Olson’s 1947 study of Herman Melville and Moby-Dick, is an anomalous book. On the one hand, it is a foundational text of Melville Studies, establishing Melville as an American Shakespeare and helping to solidify Melville’s elevated position in a canon of American literature.1 On the other hand, Call Me Ishmael also offers a bizarre recasting of Melville’s entire oeuvre, transforming the image of the nineteenth-century writer at a moment in which early practitioners of American Studies were consolidating a specifically “national imaginary” with respect to literature and history. Call Me Ishmael is simultaneously a key document of an emerging American Studies and a proleptic critique of the nationalist project of the disciplinary field. Blurring the lines between literary artist and scholarly critic, Olson sought to rethink Melville’s leviathan by reimagining Melville’s own imaginative reshaping of the world system in * Robert T. Tally Jr. is an associate professor of English at Texas State University. He is the author of Melville, Mapping and Globalization: Literary Cartography in the American Baroque Writer (2009), Kurt Vonnegut and the American Novel: A Postmodern Iconography (2011), Spatiality (2012), and Utopia in the Age of Globalization: Space, Representation, and the World System (2013). The translator of Bertrand Westphal’s Geocriticism: Real and Fictional Spaces (2011), Tally is also the editor of Geocritical Explorations: Space, Place, and Mapping in Literary and Cultural Studies (2011) and Kurt Vonnegut: Critical Insights (2013). -

Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography Or Autobiography Year Winner 1917

A Monthly Newsletter of Ibadan Book Club – December Edition www.ibadanbookclub.webs.com, www.ibadanbookclub.wordpress.com E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography or Autobiography Year Winner 1917 Julia Ward Howe, Laura E. Richards and Maude Howe Elliott assisted by Florence Howe Hall 1918 Benjamin Franklin, Self-Revealed, William Cabell Bruce 1919 The Education of Henry Adams, Henry Adams 1920 The Life of John Marshall, Albert J. Beveridge 1921 The Americanization of Edward Bok, Edward Bok 1922 A Daughter of the Middle Border, Hamlin Garland 1923 The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1924 From Immigrant to Inventor, Michael Idvorsky Pupin 1925 Barrett Wendell and His Letters, M.A. DeWolfe Howe 1926 The Life of Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing 1927 Whitman, Emory Holloway 1928 The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas, Charles Edward Russell 1929 The Training of an American: The Earlier Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1930 The Raven, Marquis James 1931 Charles W. Eliot, Henry James 1932 Theodore Roosevelt, Henry F. Pringle 1933 Grover Cleveland, Allan Nevins 1934 John Hay, Tyler Dennett 1935 R.E. Lee, Douglas S. Freeman 1936 The Thought and Character of William James, Ralph Barton Perry 1937 Hamilton Fish, Allan Nevins 1938 Pedlar's Progress, Odell Shepard, Andrew Jackson, Marquis James 1939 Benjamin Franklin, Carl Van Doren 1940 Woodrow Wilson, Life and Letters, Vol. VII and VIII, Ray Stannard Baker 1941 Jonathan Edwards, Ola Elizabeth Winslow 1942 Crusader in Crinoline, Forrest Wilson 1943 Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Samuel Eliot Morison 1944 The American Leonardo: The Life of Samuel F.B. -

Symbolic Interpretations of Moby Dick

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Master's Theses Graduate School Summer 1963 Symbolic Interpretations of Moby Dick John B. Terbovich Fort Hays Kansas State College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Terbovich, John B., "Symbolic Interpretations of Moby Dick" (1963). Master's Theses. 813. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/theses/813 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. SYMBOLIC INTERPRETATIONS OF MOBY DICK being A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Fort Hays Kansas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Fr. John B. Terbovich, O.F.M.Cap., A.B. St. Fidelis Seminary and College Approved f . Majo' Professor ABS TRACT OF THESIS Terbovich, Fr. John B., O. F. M. Cap. 1963. "Symbolical Inter- pretations of Moby Dick. 11 In my study of the various interpretations attributed to Herman Melville's novel, Moby Dick, I have become aware of the great confusion among critics of literary symbolism and the problems involved. The facts that so much has been written on Moby Dick and that so many varied interpretations have resulted seem to indicate that Moby Dick offers a challenge to the reader and that there is a deeper and more profound meaning behind this adventure story than meets the eye. It is safe to say that no American novel has stimulat ed so much thinking in the realm of literary criticism as Moby Dick. -

Herman Melville Have Been Invaluable.2

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1984 THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN AUTHOR: MELVILLE AND THE IDEA OF A NATIONAL LITERATURE DANIEL WARE REAGAN University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation REAGAN, DANIEL WARE, "THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN AUTHOR: MELVILLE AND THE IDEA OF A NATIONAL LITERATURE" (1984). Doctoral Dissertations. 1443. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1443 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

“Melville: Finding America at Sea” Checklist of Items in Exhibition

“Melville: Finding America at Sea” Checklist of Items in Exhibition Introduction, Case 1 of 1 Moby-Dick is epic prose-poem, scientific treatise, industrial exposé, philosophical exploration, travelogue, Shakespearean tale of revenge, and much more—all rolled into one whale-sized package. Melville’s book can be read as one of the first distinctively American masterpieces, embracing these diverse, disparate materials to form a whole greater than the sum of its parts. 1. Herman Melville The Whale Published in London by Richard Bentley in October 1851 Call number and to request viewing: VAULT Melville PS2384 .M6 1851m (Copy 1) The true first edition of Moby-Dick appeared in England in October 1851, in an edition of 500 copies. 2. Herman Melville Moby-Dick, or, The Whale Published in New York by Harper & Brothers in November 1851 Call number and to request viewing: VAULT Melville PS2384 .M6 1851k This first American edition shows the major variations between the texts of the American and English editions, starting with their different titles. See the case in the next room of the Trienens Galleries on the making of the Northwestern-Newberry Edition for another example of these differences. While the title Moby-Dick was hyphenated in the first edition, the whale’s name was not hyphenated in the text—the reason for which is rather unclear. This exhibition follows the common practice of hyphenating when referring to the book, but not to the whale, and not to other editions or works such as plays and films which do not hyphenate the title. Introduction, Wall Items 3.