Formulation and Topical Delivery of Lidocaine and Prilocaine with the Use of Pheroid™ Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

208135Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 208135Orig1s000 STATISTICAL REVIEW(S) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Translational Sciences Office of Biostatistics S TATISTICAL R EVIEW AND E VALUATION CLINICAL STUDIES NDA/BLA #: 208135 Drug Name: Tetracaine Hydrochloride Ophthalmic Solution 0.5% (STERI-UNIT®) Indication(s): For procedures requiring a rapid and short acting ophthalmic anesthetic Applicant: Alcon research ltd Date(s): Stamp date: April 30, 2015 PDUFA date: February 29, 2016 Review Priority: Standard Biometrics Division: DBIV Statistical Reviewer: Abel Tilahun Eshete Concurring Reviewers: Yan Wang Medical Division: Ophthalmology Clinical Team: Medical Reviewer: Jennifer Harris Project Manager: Michael Puglisi Keywords: Topical anesthesia, Pain scores, Tetracaine . Reference ID: 3875889 Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................... 4 2 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 SUBMISSION HISTORY .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.3 -

Proxymetacaine Hydrochloride Ropivacaine Hydrochloride

1870 Local Anaesthetics Preparations pore: Alcaine; Switz.: Alcaine; Turk.: Alcaine; Opticaine; USA: Ak-Taine; Alcaine; Ocu-Caine; Ophthetic; Parcaine; Venez.: Alcaine; Oftaine†; Poen- (details are given in Part 3) caina. Proprietary Preparations CH3 Multi-ingredient: Spain: Detraine. O Multi-ingredient: Canad.: Fluoracaine†; USA: Fluoracaine; Fluorocaine. N CH3 O Quinisocaine Hydrochloride (BANM, rINNM) H3C Propipocaine (rINN) O Chinisocainum Hydrochloride; Dimethisoquin Hydrochloride Propipocaína; Propipocaïne; Propipocainum; Propoxypipero- (USAN); Dimethisoquinium Chloride; Hidrocloruro de quinisocaí- NH2 caine. 3-Piperidino-4′-propoxypropiophenone. na; Quinisocaïne, Chlorhydrate de; Quinisocaini Hydrochlori- (proxymetacaine) dum. 2-(3-Butyl-1-isoquinolyloxy)-NN-dimethylethylamine hy- Пропипокаин drochloride. C17H25NO2 = 275.4. Хинизокаина Гидрохлорид CAS — 3670-68-6. NOTE. PROX is a code approved by the BP 2008 for use on single unit doses of eye drops containing proxymetacaine hydrochlo- C17H24N2O,HCl = 308.8. ride where the individual container may be too small to bear all CAS — 86-80-6 (quinisocaine); 2773-92-4 (quinisocaine the appropriate labelling information. PROXFLN is a similar hydrochloride). O code approved for eye drops containing proxymetacaine hydro- ATC — D04AB05. chloride and fluorescein sodium. ATC Vet — QD04AB05. N Pharmacopoeias. In Br. and US. BP 2008 (Proxymetacaine Hydrochloride). A white or almost H3C CH3 white, odourless or almost odourless, crystalline powder. Soluble O in water and in chloroform; very soluble in dehydrated alcohol; N practically insoluble in ether. A 1% solution in water has a pH of O CH Profile 5.7 to 6.4. Protect from light. 3 Propipocaine is a local anaesthetic (p.1850) that has been used USP 31 (Proparacaine Hydrochloride). A white to off-white, or for surface anaesthesia. -

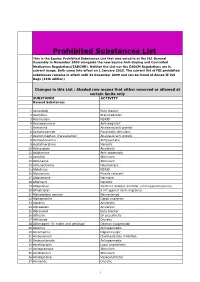

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Royal Free Hospital Drug Formulary

Royal Free Hospital Drug Formulary Title Formulary Status Section Annotation 5.3 Antiviral drugs‐>5.3.1 HIV infection‐>Nucleoside reverse ABACAVIR On Formulary transcriptase inhibitors As per HIV guidelines. Abidec® On Formulary 9.6 Vitamins‐>9.6.7 Multivitamin preparations 4.10 Drugs used in substance dependence‐>4.10.1 Alcohol ACAMPROSATE CALCIUM On Formulary dependence‐>Acamprosate 6.1 Drugs used in diabetes‐>6.1.2 Antidiabetic drugs‐>6.1.2.3 Other ACARBOSE On Formulary antidiabetic drugs 11.6 Treatment of glaucoma‐>Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and ACETAZOLAMIDE On Formulary systemic drugs 11.8 Miscellaneous ophthalmic preparations‐>11.8.2 Ocular diagnostic and peri‐operative preparations and photodynamic ACETYLCHOLINE CHLORIDE On Formulary treatment‐>Ocular peri‐operative drugs ACETYLCYSTEINE On Formulary Specific drugs‐>Analgesics (non‐opioid) Acetylcysteine On Formulary Specific drugs‐>Analgesics (non‐opioid)‐>ACETYLCYSTEINE 11.8 Miscellaneous ophthalmic preparations‐>11.8.1 Tear deficiency, ACETYLCYSTEINE On Formulary ocular lubricants, and astringents ACICLOVIR On Formulary 11.3 Anti‐infective eye preparations‐>11.3.3 Antivirals ACICLOVIR On Formulary 13.10 Anti‐infective skin preparations‐>13.10.3 Antiviral preparations 13.10 Anti‐infective skin preparations‐>13.10.3 Antiviral preparations‐ Aciclovir On Formulary >ACICLOVIR 13.5 Preparations for eczema and psoriasis‐>13.5.2 Preparations for ACITRETIN On Formulary psoriasis‐>Oral retinoids for psoriasis Removal and elimination‐>Removal from the gastro‐intestinal tract‐ Actidose‐Aqua® -

Safety Alert: Risks Associated with Ophthalmic Anesthetics

WRHA Pharmacy Program Health Sciences Centre MS-189 820 Sherbrook St. Winnipeg, Manitoba R3A 1R9 CANADA TEL: 204-787-7183 Fax: 204-787-3195 FAX: 204-787-3195 Safety Alert: Risks associated with Ophthalmic Anesthetics The self-administration of ophthalmic anesthetics by patients for the relief of eye pain should be avoided and they should not be given to patients to take home for pain relief. Vision threatening complications of topical anesthetic abuse are common. There is no indication for the use of ophthalmic anesthetics except for diagnostic and short term therapeutic purposes (the removal of a foreign body or ocular surgery) and therefore, these products should only be used under a physician’s supervision. Eye trauma resulting in a corneal abrasion (epithelial injury) is a common complaint in the Emergency department (1). A superficial corneal injury can cause intense pain causing a patient to seek medical help or immediate relief from available over the counter remedies. In Canada, only two topical ophthalmic anesthetic drugs are available commercially as single entities, proparacaine (proxymetacaine) and tetracaine (available in bottle and minim forms). Benoxinate (oxybuprocaine) is only available in combination with fluorescein (3). Lidocaine is also used in ophthalmic surgical procedures however, it is not available in the Canadian market as an ophthalmic preparation. Topical ophthalmic anesthetics function by blocking nerve conduction when applied to the cornea and conjunctiva. The ocular surface is innervated by the multiple branches of the trigeminal nerve. The cornea is supplied by the long and short ciliary nerves, the nasociliary nerve and the lacrimal nerve (4). Topical anesthetics reduce sodium permeability preventing generation and conduction of nerve impulses, increasing excitation threshold, and slowing the nerve impulse propagation. -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 1/41

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2016 ATC code ATC group / Active substance (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit DDD/1000/ day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 167,8985 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0738 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0738 A01AB09 Miconazole (O) 7088 g 0,2 g 0,0738 A01AB12 Hexetidine (O) 1951200 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+ Benzocaine (dental) 30200 pieces A01AB82 Demeclocycline+ Triamcinolone (dental) 680 g A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+ Thymol (dental) 3094 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+ Cetylpyridinium chloride (gingival) 227150 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+ Cetrimide (O) 30900 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate (O) 864720 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+ Chamomille extract (O) 370080 g A01AD90 Lidocaine+ Paraformaldehyde (dental) 405 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 47,1312 A02A ANTACIDS 1,0133 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 1,0133 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 811120 pieces 10 pieces 0,1689 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+ Magnesium hydroxide (O) 3101974 ml 50 ml 0,1292 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+ Magnesium carbonate (O) 3434232 pieces 10 pieces 0,7152 DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 46,1179 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 2,3855 A02BA02 Ranitidine (O) 340327,5 g 0,3 g 2,3624 A02BA02 Ranitidine (P) 3318,25 g 0,3 g 0,0230 A02BC Proton pump inhibitors 43,7324 A02BC01 Omeprazole -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 Bezwada (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US008O26285B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 BeZWada (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 27, 2011 (54) CONTROL RELEASE OF BIOLOGICALLY 6,955,827 B2 10/2005 Barabolak ACTIVE COMPOUNDS FROM 2002/0028229 A1 3/2002 Lezdey 2002fO169275 A1 11/2002 Matsuda MULT-ARMED OLGOMERS 2003/O158598 A1 8, 2003 Ashton et al. 2003/0216307 A1 11/2003 Kohn (75) Inventor: Rao S. Bezwada, Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2003/0232091 A1 12/2003 Shefer 2004/0096476 A1 5, 2004 Uhrich (73) Assignee: Bezwada Biomedical, LLC, 2004/01 17007 A1 6/2004 Whitbourne 2004/O185250 A1 9, 2004 John Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2005/0048121 A1 3, 2005 East 2005/OO74493 A1 4/2005 Mehta (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005/OO953OO A1 5/2005 Wynn patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2005, 0112171 A1 5/2005 Tang U.S.C. 154(b) by 423 days. 2005/O152958 A1 7/2005 Cordes 2005/0238689 A1 10/2005 Carpenter 2006, OO13851 A1 1/2006 Giroux (21) Appl. No.: 12/203,761 2006/0091034 A1 5, 2006 Scalzo 2006/0172983 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada (22) Filed: Sep. 3, 2008 2006,0188547 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada 2007,025 1831 A1 11/2007 Kaczur (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2009/0076174 A1 Mar. 19, 2009 EP OO99.177 1, 1984 EP 146.0089 9, 2004 Related U.S. Application Data WO WO9638528 12/1996 WO WO 2004/008101 1, 2004 (60) Provisional application No. 60/969,787, filed on Sep. WO WO 2006/052790 5, 2006 4, 2007. -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

OUH Formulary Approved for Use in Breast Surgery

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Formulary FORMULARY (Y): the medicine can be used as per its licence. RESTRICTED FORMULARY (R): the medicine can be used as per the agreed restriction. NON-FORMULARY (NF): the medicine is not on the formulary and should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. UNLICENSED MEDICINE – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (UNR): the medicine is unlicensed and can be used as per the agreed restriction. SPECIAL MEDICINE – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (SR): the medicine is a “special” (unlicensed) and can be used as per the agreed restriction. EXTEMPORANEOUS PREPARATION – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (EXTR): the extemporaneous preparation (unlicensed) can be prepared and used as per the agreed restriction. UNLICENSED MEDICINE – NON-FORMULARY (UNNF): the medicine is unlicensed and is not on the formulary. It should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. SPECIAL MEDICINE – NON-FORMULARY (SNF): the medicine is a “special” (unlicensed) and is not on the formulary. It should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. EXTEMPORANEOUS PREPARATION – NON-FORMULARY (EXTNF): the extemporaneous preparation (unlicensed) cannot be prepared and used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. CLINICAL TRIALS (C): the medicine is clinical trial material and is not for clinical use. NICE TECHNOLOGY APPRAISAL (NICETA): the medicine has received a positive appraisal from NICE. It will be available on the formulary from the day the Technology Appraisal is published. Prescribers who wish to treat patients who meet NICE criteria, will have access to these medicines from this date. However, these medicines will not be part of routine practice until a NICE TA Implementation Plan has been presented and approved by MMTC (when the drug will be given a Restricted formulary status). -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

Clonidine As Adjuvant for Oxybuprocaine, Bupivacaine Or

1 Clonidine as adjuvant for oxybuprocaine, bupivacaine or dextrorphan has a significant peripheral action in intensifying and prolonging analgesia in response to local dorsal cutaneous noxious pinprick in rats Yu-Wen Chen, Ph.D.,1,2 Chin-Chen Chu, M.D., Ph.D.,3 Yu-Chung Chen, M.S.,4 Ching-Hsia Hung, Ph.D.,5,* Meng-I Hsueh, B.S.,1 Jhi-Joung Wang, M.D., Ph.D.3 1 Department of Physical Therapy, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan 2 Graduate Institute of Neural and Cognitive Sciences, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan 3 Department of Medical Research, Chi-Mei Medical Center, Tainan, Taiwan 4 Division of Physical Therapy, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Cheng Hsin General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan 5 Institute & Department of Physical Therapy, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan *Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Ching-Hsia Hung, PhD, Department of Physical Therapy, National Cheng Kung University, No.1 Ta-Hsueh Road, Tainan, Taiwan Tel: 886-6-2353535 ext 5939 Fax: 886-6-2370411 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Abstract The aim of the study was to evaluate co-administration of clonidine with oxybuprocaine (ester type), bupivacaine (amide type) or dextrorphan (non-ester or non-amide type) and to see whether it could have a peripheral action in enhancing local anesthesia on infiltrative cutaneous analgesia in rats. Cutaneous analgesia was evaluated by a block of the cutaneous trunci muscle reflex (CTMR) in response to local dorsal cutaneous noxious pinprick in rats. The analgesic effect of the addition of clonidine with oxybuprocaine, bupivacaine or dextrorphan by subcutaneous injection was evaluated. -

National Drugs and Poisons Schedule Committee

National Drugs and Poisons Schedule Committee Record of the Reasons 36th Meeting 15-17 October 2002 The Record of the Reasons contains the basis of scheduling decisions and other outcomes arising from the meeting. Please note that the Secretariat is moving towards including the edited minutes as the Record of the Reasons. With this document, we have included edited extracts relating to scheduling considerations for OTC medicines, domestic poisons and certain matters related to pesticides. The Secretariat is hopeful of including the edited minutes for all sectors following consultation with the respective industry bodies. National Drugs and Poisons Schedule Committee Record of the Reasons for Meeting 36 - October 2002 i TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY..........................................................................................................................................IV 2. PROPOSED CHANGES/ADDITIONS TO PARTS 1 TO 3 AND PART 5 OF THE STANDARD FOR THE UNIFORM SCHEDULING OF DRUGS AND POISONS............................. 1 2.1 SUSDP, PART 1......................................................................................................................... 1 2.1.1 Definition in Part 1 of the SUSDP for “aqueous preparations” .......................................... 1 2.2 SUSDP, PART 2......................................................................................................................... 1 2.2.1 Variation of Requirement for Clause 7(1)(d)......................................................................