Dissertation Approv Ed By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgetown Preparatory School Academic Catalogue 2016-2017

Georgetown Preparatory School Academic Catalogue 2016 -2017 0 Mission Statement: Georgetown Prep is a Catholic, Jesuit, day and boarding school whose mission is to form men of competence, conscience, courage, and compassion; men of faith; men for others. 1 -2- orientation toward God and establishing a Profile of a Graduate at relationship with a religious tradition and/or community. What is said here, respectful of the Graduation conscience and religious background of the individual, also applies to the non-Catholic graduate of a Jesuit high school. The level of theological The Profile of a Georgetown Prep Graduate is a understanding of the Jesuit high school graduate will model and framework for each student to consider, naturally be limited by the student’s level of religious aspire to, and reflect upon. The concept of the and human development. "Graduate at Graduation" is unique to the Jesuit mission of education and is embraced by the entire Loving network of Jesuit schools in the United States. It By graduation, the Georgetown Prep student is was first developed in 1980 by the Jesuit Secondary continuing to form his own identity. He is moving Education Association. beyond self-interest or self-centeredness in close relationships. The graduate is beginning to be able to The characteristics of the Profile describe the risk some deeper levels of relationship in which one graduate from various perspectives. Jesuit can disclose self and accept the mystery of another education, however, is, has been, and always will be person and cherish that person. Nonetheless, the focused on whole person education: mind, spirit, and graduate’s attempt at loving, while clearly beyond body. -

Explore Adoption at CSS

2016 2017 ANNUAL REPORT SLAUGHTER FAMILY Explore Adoption at CSS LEWTON FAMILY Domestic and International Adoptions SCHERR FAMILY Annual Report CATHOLIC SOCIAL SERVICES 2017-2018 Newly Elected 2016-2017 LEADERSHIP Officers and Directors OFFICERS: Terms Expire 6/30/2017 President – Susan Meyer Vice President – Susan Raposa Secretary – Lisa Wesolick Treasurer – Cassie Ward Executive Director – Jim Kinyon DIRECTORS: Terms Expire 6/30/2017 Lisa Kendrick Wesolick, Kendrick & Company David DiMaria Susan Raposa Susan Raposa Lisa Wesolick Cassie Ward Mary Kjerstad Dr. Steve Massopust, Physician President Vice President Treasurer Secretary Catholic Social Services Catholic Social Services Catholic Social Services Catholic Social Services Terms Expire 6/30/2018 Brenda Wills, RPM Solutions Deacon Marlon Leneaugh, Diocese of Rapid City Sherri Raforth, Interpreter Matt Stone, Civil Engineer Terms Expire 6/30/2019 Susan Meyer, Attorney Cassie Ward, Century Properties Rick Soulek, Diocese of Rapid City Kathleen Barrow, Attorney Mary Kjerstad PERMANENT BOARD SEAT Richard Rangel Dr. Steve Massopust Sheila Lien Jim Kinyon The Most Reverend Robert Gruss, Newly Elected Director Newly Elected Director Newly Elected Director Executive Director Bishop of Rapid City Catholic Social Services Catholic Social Services Catholic Social Services Catholic Social Services CATHOLIC SOCIAL SERVICES 2016-2017 600 Attend CSS Annual Banquet Last Year PROFESSIONAL STAFF EXECUTIVE STAFF: Jim Kinyon - Executive Director DEPARTMENT HEADS: Lorinda Collings, Director - Human Resources/Finance -

Download The

VOLUME 44 NUMBER 1 DIOCESE OF RAPID CITY, Diocesan Website: www.rapidcitydiocese.org SOUTH DAKOTA Serving Catholics in Western South Dakota since May 1973 Reservation and Rural Ministry Planning Team Vatican A Season of Change, 2 Creating vibrant parish clusters Diocesan Priests Parish gives Assignments, 4 By Laurie Hallstrom took from the Catholic Leader- ship Institute of Wayne, Pa.) voice to At the center of Catholic “Good Leaders, Good Shep- worship is the church commu- herds,” said Father Biegler. “It women nity where a parishioner feels a could be used in the future for VATICAN CITY sense of belonging. Pending other areas of the diocese.” (CNS) — A new changes to church clusters are After months of considera- Vatican magazine will give attention intended to bring new spiritual tion three new parish configu- life to the faithful in the north- to women's voices, rations were recommended to something that ern tier of the Diocese of Rapid the bishop. (See page 5 for a often has been City. letter from Bishop Gruss de- missing in the A combined team of 13 tailing changes that will take church despite clergy and laity has spent the place July 1.) women's important Priority Plan of the Diocese past 15 months assessing the “When parish representa- role in announcing of Rapid City, 13-16 pastoral needs of parishes in tives first came on the team the Gospel, said Year of Mercy Pilgrimage Harding, Perkins and Corson they were biased toward their Cardinal Pietro Parolin. “If we do not listen attentively to the voice of to St. -

M Hill: a Century of Mines Pride Dr. Paul Gnirk

M Hill: A Century of Mines Pride Dr. Paul Gnirk: A Lifetime of Achievements Stacy Collins’ New Era of Hardrocker Football Mines Celebrates Native American Community PRESIDENT’S LETTER | Dear Colleagues, Excel, innovate, contribute, and celebrate. These words all come to mind as one reads of the achievements and advancements of the Mines alumni, faculty, staff, and students in this Hardrock. It is my hope that you will feel a sense of Mines Pride as you read of the scholarly and athletic success as well as the community involvement of our Mines family. Excel – Dr. Paul Gnirk (MinE59), and other alumni, Larry Pearson (ME72), Jeane (CE77) and John Hull (MinE77), and Dr. Scott Kenner (CE77), clearly excel on so many levels. Dr. Umesh Korde, the Pearson Chair in Mechanical Engineering (ME), featured in this issue, and his faculty colleagues excel and share their successes with our students and others globally. Innovate – Drs. Kyle Riley and Charles Tolle, as well as several other faculty, including Robert A. Wharton, PhD, Drs. Foster Sawyer (GEOL90) and Carter Kerk, and Shashi Kanth (M.S. MinE93), continue to School of Mines create innovative opportunities for Mines learning in diverse environments. Veteran student, Ryan Brown, and 2012 graduates Andrew Muxen (ME10) and Anthony Kulesa (CE12), as President well as the Mines Team India, capture the spirit of innovation along with others noted here. Contribute – Mines alumnus, Larry, and Linda Pearson’s funding of the endowed ME chair, the Hulls’ professorship in Mining Engineering, and others who make generous contributions to the Building the Dream campaign contribute the fiscal capacity to enhance the quality of teaching and research at Mines, affording greater opportunities to attract and retain highly qualified students and faculty. -

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Name and Other Data

Georgetown Prep Immersion Program Georgetown Prep’s immersion program is: solidarity with the poor and marginalized. an understanding of self that includes the other. grounded in “a faith that does justice.” living simply. a radical view of the gospel message of love through action. an experience of being a man for and with others. Application procedure: Completed applications are due in the Christian Service Office, G114B, by 3:00 pm on Tuesday, January 9. Please submit a hard copy only. Applications received by the due date will receive priority. Applications will be processed and applicants will be notified by the end of January. Criteria for acceptance: There are usually more qualified applicants than spaces available. We will look to accept individuals who demonstrate the following characteristics, among others: o Open to Growth o Committed to Doing Justice o Loving o Religious o Intellectually Competent The application is made to the program not to a particular trip. Applicants are asked to indicate at least three options. Each trip has limited spaces, and flexibility ensures that we are able to serve in each of the areas below. Immersion Trips: Apopka -- June 10-16: Prep will partner with the Hope Community Center in Apopka, Florida, just outside of Orlando. Hope Community Center was founded by the Sisters of Notre Dame to serve community members going through hard times. Apopka has a large migrant community from all countries in Latin America that have endured the struggles of immigration for a long time. Students will stay in pairs with families in the community, eating meals, conversing, and playing games. -

Certified Teacher Employment Application

RED CLOUD INDIAN SCHOOL 100 Mission Drive; Pine Ridge, SD 57770 PHONE: (605) 867-5888 (605) 867-5491 FAX: (605) 867-1291 EMAIL: [email protected] CERTIFIED STAFF APPLICATION FORM This application is submitted for the position of _________________________________ Date __________________________ Name ____________________________________________________ Social Security Number __________________________ Address_____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Street City/State Zip Code Email Address ____________________________ Home Phone ____________________ Business Phone _________________ EDUCATIONAL RECORD List name and location of institution, year(s) attended, degree/major(s). List most recent first. NAME LOCATION YEARS ATTENDED DEGREE/MAJOR(S) 1. ________________________________ _____________________ _____________________ _______________________ 2. ________________________________ _____________________ _____________________ _______________________ 3. ________________________________ _____________________ _____________________ _______________________ Do you hold a valid South Dakota certificate? ___________ Number _______________________ Expiration Date __________ Do you hold a valid certificate in another state? _________ State Name ____________________ Expiration Date __________ List Endorsements/Teaching Major/Additional Subjects ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: a History of Crow Creek Tribal School

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2000 Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School Robert W. Galler Jr. Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Galler, Robert W. Jr., "Environment, Cultures, and Social Change on the Great Plains: A History of Crow Creek Tribal School" (2000). Dissertations. 3376. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3376 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENVIRONMENT, CULTURES, AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE GREAT PLAINS: A HISTORY OF CROW CREEK TRIBAL SCHOOL by Robert W. Galler, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2000 Copyright by Robert W. Galler, Jr. 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people provided assistance, suggestions, and support to help me complete this dissertation. My study of Catholic Indian education on the Great Plains began in Dr. Herbert T. Hoover's American Frontier History class at the University of South Dakota many years ago. I thank him for introducing me to the topic and research suggestions along the way. Dr. Brian Wilson helped me better understand varied expressions of American religious history, always with good cheer. -

At Creighton Prep

A Day in the Life at Creighton Prep A DAY IN THE LIFE 4 TOMORROW LABS 10 NEW FOOTBALL HELMETS 13 SUMMER 2017 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 10 I know that many of the events that get Creighton Prep noticed by the BUILD SPACE Volume 61 No. 1 Summer 2017 larger community are the academic accomplishments of various students, SOUTH END OF EXISTING STORAGE AREA Issue Date: 09 May, 2017 Project Number: 17052 CREIGHTON PREPARATORY SCHOOL INNOVATION LAB Design Phase: SD the successes in our athletics program and initiatives such as the lunchtime FILE LOCATION: H:\2017\17052 CREIGHTON PREPARATORY FACILITY UPGRADES\DESIGN\STEM LAB\02 SD\17052_STEM LAB DESIGN.DWG PLOTTED: 5/9/2017 8:35:24 AM Published by: Creighton Prep dining service. For those of us who work here, however, what makes Prep 7400 Western Avenue just as special are the everyday wonders that involve moments such as Omaha, NE 68114-1878 twice daily prayer, students working together on classroom problems and 4 13 402.393.1190 our amazing faculty who dedicate themselves to helping these young men www.creightonprep.org understand and become well versed in a range of subjects. President: Fr. Tom Neitzke, SJ In the following pages, my hope is that the section on “A Day in the Life 16 Creighton Prep 4 A Day in the Life at Creighton Prep [email protected] at Creighton Prep” gives you a sense of what it’s like to be here, observing What happens at Creighton Prep on a typical day? Workplace Gatherings those wonderful moments that take place daily at the school. -

Annual Report 2016

Annual Report 2016 1. Enrollment 2. College Placement 3. Student Ethnic Diversity 4. Student Religious Diversity 5. Tuition and Fees 6. Financial Aid 7. Administration/Faculty/Staff 8. Faculty Ethnic Diversity 1. ENROLLMENT 2016 – 2017 US East Totals by Class Annual Totals 9th 10th 11th 12th 6th-8th* 16-17 15-16 +/- Boston College High School 308 278 322 303 369 1,580 1,578 +2 Canisius High School 190 206 224 210 830 879 -40 Cheverus High School 96 116 110 113 435 474 -39 Cristo Rey Jesuit Atlanta 140 121 128 0 389 278 +111 Cristo Rey Jesuit Baltimore 103 90 72 85 350 348 +2 Fairfield College Preparatory 188 244 218 220 870 900 -30 Fordham Preparatory 258 253 280 214 1,005 981 +24 Georgetown Preparatory 122 132 130 112 496 496 0 Gonzaga College High School 246 245 235 231 957 963 -6 Loyola Blakefield 178 194 180 168 229 949 956 -7 Loyola School 49 48 53 53 203 208 -5 McQuaid Jesuit 150 151 169 154 309 933 932 +1 Regis High School 135 134 130 133 532 533 -1 Scranton Preparatory 177 197 186 173 733 764 -31 St. Joseph's Preparatory 257 197 225 227 906 884 +22 St. Peter's Preparatory 245 252 237 225 959 938 +21 Xavier High School 258 267 274 278 1,077 1,098 -21 US Midwest Totals by Class Annual Totals 9th 10th 11th 12th 6th-8th* 16-17 15-16 +/- Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory 193 204 220 178 795 781 +14 Christ the King Jesuit 111 94 67 73 345 329 +16 Creighton Preparatory 271 254 255 245 1,025 1,024 +1 Cristo Rey Jesuit Chicago 168 152 131 116 567 564 +3 Cristo Rey Jesuit Milwaukee 118 116 0 0 234 NA Cristo Rey Jesuit Twin Cities 145 141 84 85 455 408 +47 Loyola High School 42 44 26 33 145 140 +5 Loyola Academy 510 512 514 511 2,047 2,118 -71 Marquette University HS 269 246 273 265 1,053 1,074 -21 Red Cloud Indian School 51 68 53 48 380 600 NR St. -

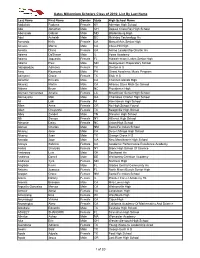

Gates Millennium Scholars Class of 2016: List by Last Name 1 of 20

Gates Millennium Scholars Class of 2016: List By Last Name Last Name First Name Gender State High School Name Abdullahi Fadumo Female KY Atherton High School Abe Jonathan Male OH Depaul Cristo Rey High School Aborisade Gabriel Male MD Bladensburg High Abul Achaiah Male DC Mckinley Technology Hs Acevedo Kelly Female CA Manual Arts Senior High Aceves Marco Male CA Citrus Hill High Acosta Diana Female CA Animo Leadership Charter Hs Adams DeShawn Male IL Voise Academy Adams Jaquesta Female FL Hialeah-miami Lakes Senior High Adams Paul Male MD Georgetown Preparatory School Adjagbodjou Adinawa Female TX Denton H S Aing Raymond Male PA Girard Academic Music Program Akinyemi Grace Female TX Elsik H S Alcantar Ernesto Male CA Channel Islands High Alcaraz Martin Male CA Alliance Stern Math Sci School Aldana Bryan Male NC Providence High Aleman Hernandez Amelia Female LA Broadmoor Senior High School Alemayehu Mati Male GA Chamblee Charter High School Ali Laki Female MI Hamtramck High School Allen Anna Female OR No High School Found Allen Cheyenne Female TX Seagoville High School Alley Zander Male TN Dresden High School Alli Soraya Female NY Hillcrest High School Almonte Daisy Female NC Union High School Alonzo Charles Male NM Santa Fe Indian School Alvarez Jose Male CA Desert Mirage High School Alvarez Juan Male TX Orange Grove H S Amador Jose Male GA New Manchester High School Amaya Sabrina Female CA Academic Performance Excellence Academy Ambia Shanjida Female NY Bronx High School Of Science Ambrosio Luis Male OK Southeast Hs Andrews Darrell Male -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS ASSOCIATION OF JESUIT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES (AJCU) Page Map of AJCU Institutions ............................................................................................................................................ 4 History of the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities ............................................................................... 5 Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Board Committees ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 AJCU Staff and Programs ............................................................................................................................................. 8 JesuitNET ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 AJCU Federal Relations Network .............................................................................................................................. 10 AJCU Communications Network ............................................................................................................................. 13 AJCU Conferences ......................................................................................................................................................