Janącek's London Visit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

The Kapralova Society Journal Spring 2005

Volume 3, Issue 1 The Kapralova Society Journal Spring 2005 A Journal of Women in Music Love’s Labour’s Lost: Martinu, Kapralova and Hitler1 By Alan Houtchens "Love's Labour's Lost." I have several significant works under the watchful shamelessly appropriated Shakespeare's eye of Martinu, who, for his part, was title for a play of quite another kind, a trag- touched to the very core of his being by his edy that was played out only once, during beautiful young pupil. the years 1938 and 1939, involving the fol- Since the death in 1978 of Mar- lowing principal characters: tinu's widow, Charlotte, (they were married in 1931), and especially after the appear- Bohuslav Martinu, the Czech composer; ance of Jiri Mucha's book Podivne lasky born in 1890 (Strange Loves) in 1988, the romantic at- tachment that developed between Kapra- Vitezslava Kapralova, brilliant Czech com- lova and Martinu has become common poser and conductor; 25 years younger knowledge.2 Musical evidence of Kapra- than Bohuslav Martinu lova and Martinu's intimacy may be discov- Special points of interest: ered in Martinu's Eight Madrigals for mixed Otakar Sourek, by profession a civil engi- voices on texts selected from Moravian folk neer in Prague, by avocation a musicolo- poetry, composed in 1939. In the biogra- · Otakar Sourek’s corre- gist, music editor, and music critic; seven phy of Martinu written in 1961 by his close spondence with Bohuslav years older than Martinu friend and trusted confidant, Milos Safra- Martinu and Vitezslava nek, the lyrics of the Madrigals are -

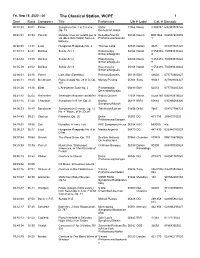

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, Sep 18, 2020 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 40:01 Paine Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Ulster 11966 Naxos 8.559747 636943974728 Op. 23 Orchestra/Falletta 00:42:3102:34 Puccini Quando m'en vo' soletta per la Netrebko/Vienna 09185 Decca B001566 028947829478 via (Musetta's Waltz) from La Philharmonic/Noseda 1 boheme 00:46:0513:38 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 Thomas Labe 04785 Dorian 9025 053473025128 01:01:13 42:21 Delibes Sylvia: Act 1 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 01:44:3419:55 Delibes Sylvia: Act 2 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 02:05:59 29:02 Delibes Sylvia: Act 3 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 02:36:0103:10 Ponce Little Star (Estrellita) Perlman/Sanders 00116 EMI 49604 077774960427 02:40:1119:45 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 28 in A, Op. Murray Perahia 05304 Sony 93043 827969304327 101 03:01:2619:16 Bizet L'Arlesienne Suite No. 2 Philharmonia 06499 EMI 62853 077776285320 Orchestra/Karajan 03:21:4205:03 Hoffstetter Serenade (Andante cantabile) Kodaly Quartet 11034 Naxos 8.558180 636943818022 03:27:45 31:38 Chausson Symphony in B flat, Op. 20 Boston 06919 BMG 60683 090266068326 Symphony/Munch 04:00:5316:47 Boccherini Symphony in D minor, Op. 12 Tafelmusik/Lamon 01856 DHM 7867 054727786723 No. 4 "House of the Devil" 04:18:40 09:21 Sibelius Finlandia, Op. 26 Berlin 00365 DG 413 755 28941375520 Philharmonic/Karajan 04:29:0129:56 Suk Pohadka, A Fairy Tale BBC Symphony/Hrusa 06384 BBC MM300 n/a 05:00:2706:17 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. -

178 Chapter 6 the Closing of the Kroll: Weimar

Chapter 6 The Closing of the Kroll: Weimar Culture and the Depression The last chapter discussed the Kroll Opera's success, particularly in the 1930-31 season, in fulfilling its mission as a Volksoper. While the opera was consolidating its aesthetic identity, a dire economic situation dictated the closing of opera houses and theaters all over Germany. The perennial question of whether Berlin could afford to maintain three opera houses on a regular basis was again in the air. The Kroll fell victim to the state's desire to save money. While the closing was not a logical choice, it did have economic grounds. This chapter will explore the circumstances of the opera's demise and challenge the myth that it was a victim of the political right. The last chapter pointed out that the response of right-wing critics to the Kroll was multifaceted. Accusations of "cultural Bolshevism" often alternated with serious appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of any given production. The right took issue with the Kroll's claim to represent the nation - hence, when the opera tackled works by Wagner and Beethoven, these efforts were more harshly criticized because they were perceived as irreverent. The scorn of the right for the Kroll's efforts was far less evident when it did not attempt to tackle works crucial to the German cultural heritage. Nonetheless, political opposition did exist, and it was sometimes expressed in extremely crude forms. The 1930 "Funeral Song of the Berlin Kroll Opera", printed in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, may serve as a case in point. -

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

Monday Playlist

February 10, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “I pay no attention whatever to anybody's praise or blame. I simply follow my own feelings.” — WA Mozart Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Elgar The Spanish Lady Suite Guildhall String Ensemble/Salter RCA 7761 07863577612 00:14 Buy Now! Goldmark Sakuntala (Concert Overture), Op. 13 Budapest Philharmonic/Korodi Hungaroton 12552 N/A Trio in B flat for Clarinet, Horn & Piano, 00:32 Buy Now! Reinecke Campbell/Sommerville/Sharon EMI 81309 774718130921 Op. 274 Watkinson/City of London 01:00 Buy Now! Vivaldi Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 4 No. 4 Naxos 8.553323 730099432320 Sinfonia/Kraemer 01:09 Buy Now! Grieg Holberg Suite, Op. 40 English Chamber Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 K. & M. Labeque/Philharmonia 01:31 Buy Now! Bruch Concerto for Two Pianos, Op. 88a Philips 432 095 028943209526 Orchestra/Bychkov Nicolet/Netherlands Chamber 02:01 Buy Now! Bach, C.P.E. Flute Concerto in A minor Philips 442 592 028944259223 Orchestra/Zinman Academy of St. Martin-in-the- 02:26 Buy Now! Mozart Symphony No. 21 in A, K. 134 Philips 422 610 028942250222 Fields/Marriner 02:47 Buy Now! Handel Trio Sonata in F, Op. 2 No. 4 Heinz Holliger Wind Ensemble Denon 7026 N/A 03:01 Buy Now! Wagner Liebestod ~ Tristan und Isolde Price/Philharmonia/Lewis RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 03:09 Buy Now! Janacek Pohadka (Fairy Tale) Alisa and Vivian Weilerstein EMI Classics 73498 724357349826 03:22 Buy Now! Dvorak Symphony No. -

Harmony in the Heartland: a Concert for Peace - Program

Wright State University CORE Scholar Accords Ephemera Accords: Peace, War, and the Arts 10-25-2015 Harmony in the Heartland: A Concert for Peace - Program CELIA Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/celia_accords_ephemera Part of the History Commons Repository Citation CELIA (2015). Harmony in the Heartland: A Concert for Peace - Program. This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Accords: Peace, War, and the Arts at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accords Ephemera by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARMONY IN THE HEARTLAND A CONCERT FOR PEACE SUNDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2015 7:30 P.M. BENJAMIN AND MARIAN SCHUSTER PERFORMING ARTS CENTER WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC Program Wright State University Fanfare .......................................Steve Hampton Trumpet Ensemble WSU Alma Mater.....................Thomas Whissen/arr. William Steinohrt lyrics David Lee Garrison ETHOS and Chamber Orchestra Jubilant Song .............................................................................. Scott Farthing Combined Choirs and Chamber Orchestra HineReflections: ma tov ...........................................................................Twenty Years of the Dayton Peace Accordsarr. Neil Ginsberg Emily Watkins, flute Cappella .......................................................................................Gene Schear Peter Keates, baritone Lean Away ..........................................................arr. -

Ludwig Van BEETHOVEN

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN Romance cantabile, WoO 207 Violin Concerto in C major, WoO 5 Jakub Junek, Violin Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra Pardubice Marek Štilec, Conductor Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Romance cantabile, WoO 207 Violin Concerto in C major, WoO 5 Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn in counterpoint and with Salieri in Italian word- in 1770. His father was still employed as setting and the introductions he brought with a singer in the chapel of the Archbishop- him from Bonn ensured a favourable reception Elector of Cologne, of which his grandfather, from leading members of the nobility. His after whom he was named, had served as patrons, over the years, acted towards him Kapellmeister. The family was not a happy with extraordinary forbearance and generosity, one, with his mother always ready to reproach tolerating his increasing eccentricities. These Beethoven’s father with his own inadequacies, were accentuated by the onset of deafness his drunkenness and gambling, with the at the turn of the century and the necessity of example of the old Kapellmeister held up as abandoning his career as a virtuoso pianist in a standard of competence that he was unable favour of a concentration on composition. to match. In due course Beethoven followed During the following 25 years Beethoven family example and entered the service of the developed his powers as a composer. His early court, as organist, harpsichordist and string compositions had reflected the influences of the player, and his promise was such that he was age, but in the new century he began to enlarge sent by the Archbishop to Vienna for lessons the inherent possibilities of classical forms. -

LEOŠ JANÁČEK Born July 3, 1854 in Hukvaldy, Moravia, Czechoslovakia; Died August 12, 1928 in Ostrava

LEOŠ JANÁČEK Born July 3, 1854 in Hukvaldy, Moravia, Czechoslovakia; died August 12, 1928 in Ostrava Taras Bulba, Rhapsody for Orchestra (1915-1918) PREMIERE OF WORK: Brno, October 9, 1921 Brno National Theater Orchestra František Neumann, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 23 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: piccolo, three flutes, two oboes, English horn, E-flat and two B-flat clarinets, three bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, organ and strings By 1914, the Habsburg dynasty had ruled central Europe for over six centuries. Rudolf I of Switzerland, the first of the Habsburgs, confiscated Austria and much surrounding territory in 1276, made them hereditary family possessions in 1282, and, largely through shrewd marriages with far-flung royal families, the Habsburgs thereafter gained control over a vast empire that at one time stretched from the Low Countries to the Philippines and from Spain to Hungary. By the mid-19th century, following the geo-political upheavals of the Napoleonic Wars, the Habsburg dominions had shrunk to the present territories of Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, a considerable reduction from earlier times but still a huge expanse of land encompassing a great diversity of national characteristics. The eastern countries continued to be dissatisfied with their domination by the Viennese monarchy, however, and the central fact of the history of Hungary and the Czech lands during the 19th century was their striving toward independence from the Habsburgs. The Dual Monarchy of 1867 allowed the eastern lands a degree of autonomy, but ultimate political and fiscal authority still rested with Emperor Franz Joseph and his court in Vienna. -

« a Window to the Soul »: the Moravian Folklore in Leoš Janáýek's Works

« A WINDOW TO THE SOUL »: THE MORAVIAN FOLKLORE IN LEOŠ JANÁýEK'S WORKS Ph. D. Haiganuú PREDA-SCHIMEK Musicologist, Vienna Born in 1971, graduate of the University of Music in Bucharest, professor Grigore Constantinescu’s class; after graduation, music editor at the Romanian Broadcasting Society (1993-1995 and July – December 1996), Ph. D. in musicology at the University of Music in Bucharest (2002). Established in Vienna since 1997, where she lives today. Between 1995-1997, she had a doctoral scholarship at Österreichischer Akademischer Austauschdienst (ÖAAD) and between 1999-2002 she was a scientific collaborator of the University of La Rioja (Logroño, Spain). As a researcher attached to the Institute of Theory, Analysis and History of Music of the University of Music in Vienna, she conducted research projects under the aegis of the Austrian Scientific Community (2004, 2005-2006, 2011), of the Commune of Vienna (2007) of the Ministry of Science and Research, Austria (2007-2010); in 2008, she was visiting researcher at the Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherches Centre-Européennes (Paris, Université IV, Sorbonne). Participations in international conferences (Romania, Austria, United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany, France, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Serbia), studies published among others in the Musicologica Austriaca (Vienna), Österreichische Musikzeitschrift (Vienna), Musurgia. Analyse et pratique musicales (Paris), Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa (Leipzig); editorial debut with the volume Form and Melody between Classicism and Romanticism at Editura Muzicală (Bucharest, 2003). Scientific reviewer of the publications Musicology Today (University of Music, Bucharest) and Musicology Papers (Academy of Music, Cluj-Napoca). Since 2007, collaborator of the Radio România Muzical, as correspondent. Lectures delivered at the University of Music and Dramatic Arts in Vienna (2009) and within the Master’s programme of Balkan Studies (University of Vienna, Institute for the Danube Area and Central Europe - 2009, 2011). -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present Composers

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers R-Z ALEXANDER RAICHEV (1922-2003, BULGARIAN) Born in Lom. He studied composition with Assen Karastoyanov and Parashkev Hadjiev at the Sofia State Conservatory and then privately with Pancho Vladigerov. He went on for post-graduate studies at the Liszt Music Academy in Budapest where he studied composition with János Viski and Zoltán Kodály and conducting with János Ferencsik. He worked at the Music Section of Radio Sofia and later conducted the orchestra of the National Youth Theatre prior to joining the staff of the State Academy of Music as lecturer in harmony and later as professor of harmony and composition. He composed operas, operettas, ballets, orchestral, chamber and choral works. There is an unrecorded Symphony No. 6 (1994). Symphony No. 1 (Symphony-Cantata) for Mixed Choir and Orchestra "He Never Dies" (1952) Konstantin Iliev/Bulgarian A Capella Choir "Sv. Obretanov"/Sofia State Philharmonic Orchestra BALKANTON BCA 1307 (LP) (1960s) Vasil Stefanov/Bulgarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus BALKANTON 0184 (LP) (1950s) Symphony No. 2 "The New Prometheus" (1958) Vasil Stefanov/Bulgarian Radio Symphony Orchestra BALKANTON BCA 176 (LP) (1960s) Yevgeny Svetlanov/USSR State Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1965) ( + Vladigerov: Piano Concertos Nos. 3 and 4 and Marinov: Fantastic Scenes) MELODIYA D 016547-52 (3 LPs) (1965) Symphony No. 3 "Strivings" (1966) Dimiter Manolov/Sofia State Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Bulgaria-White, Green, Red Oratorio) BALKANTON BCA 2035 (LP) (1970s) Ivan Voulpe/Bourgas State Symphony Orchestra ( + Stravinsky: Firebird Suite) BALKANTON BCA 1131 (LP) (c. -

A Survey of Czech Piano Cycles: from Nationalism to Modernism (1877-1930)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM NATIONALISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) Florence Ahn, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Larissa Dedova Piano Department The piano music of the Bohemian lands from the Romantic era to post World War I has been largely neglected by pianists and is not frequently heard in public performances. However, given an opportunity, one gains insight into the unique sound of the Czech piano repertoire and its contributions to the Western tradition of piano music. Nationalist Czech composers were inspired by the Bohemian landscape, folklore and historical events, and brought their sentiments to life in their symphonies, operas and chamber works, but little is known about the history of Czech piano literature. The purpose of this project is to demonstrate the unique sentimentality, sensuality and expression in the piano literature of Czech composers whose style can be traced from the solo piano cycles of Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884), Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), Leoš Janáček (1854-1928), Josef Suk (1874-1935), Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1935) to Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942). A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM ROMANTICISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) by Florence Ahn Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2018 Advisory Committee: Professor Larissa Dedova, Chair Professor Bradford Gowen Professor Donald Manildi Professor