Hebrew Bible ®

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisdom in Daniel and the Origin of Apocalyptic

WISDOM IN DANIEL AND THE ORIGIN OF APOCALYPTIC by GERALD H. WILSON University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 In this paper, I am concerned with the relationship of the book of Daniel and the biblical wisdom literature. The study draws its impetus from the belief of von Rad that apocalyptic is the "child" of wisdom (1965, II, pp. 304-15). My intent is to test von Rad's claim by a study of wisdom terminology in Daniel in order to determine whether, in fact, that book has its roots in the wisdom tradition. Adequate evidence has been gathered to demonstrate a robust connection between the nar ratives of Daniel 1-6 and mantic wisdom which employs the interpreta tion of dreams, signs and visions (Millier, 1972; Collins, 1975). Here I am concerned to dispell the continuing notion that apocalyptic as ex hibited in Daniel (especially in chapters 7-12) is the product of the same wisdom circles from which came the proverbial biblical books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job and the later Ben Sirach. 1 I am indebted to the work of Why bray ( 1974), who has dealt exhaustively with the terminology of biblical wisdom, and to the work of Crenshaw (1969), who, among others, has rightly cautioned that the presence of wisdom vocabulary is insufficient evidence of sapiential influence. 2 Whybray (1974, pp. 71-154) distinguishes four categories of wisdom terminology: a) words from the root J:ikm itself; b) other characteristic terms occurring only in the wisdom corpus (5 words); c) words char acteristic of wisdom, but occurring so frequently in other contexts as to render their usefulness in determining sapiential influence questionable (23 words); and d) words characteristic of wisdom, but occurring only occasionally in other OT traditions (10 words). -

Communications

COMMUNICATIONS DIVINE JUSTICE tov 10. Why cannot Rabbi Granatstein To THE EDITOR OF TRADITION: accept the traditional explanation of Jonah's conduct namely: Jonah In Rabbi Granatstein's recent knew that Nineveh was likely to article "Theodicy and Belief (TRA- repent in contrast with the conduct DITION, Winter 1973), he sug- of Israel who had had ample warn- gests that Jonah's motivation in ings of doom without responding trying to escape his mission to to them. The fate of Israel would Nineveh was that he could not ac- be negatively affected by an action cept "the unjustifiable selectivity of Jonah. Rather than become the involved in Divine "descent"; that willng instrument of his own peo- God's desire to save Nineveh is ple's destruction, Jonah preferred "capricious and violates the univer- self-destruction to destruction of sal justice in which Jonah be- his people. In a conflct between lieves." These are strong words loyalty to his people and loyalty which are not supported by quo- to God Jonah chose the former _ tations -from traditional sources. to his discredit, of course. In this Any student of Exodus 33: 13 is vein, Jonah's actions are explained familar with Moses's quest for un- by Redak, Malbin, Abarbarnel derstanding the ways of Divine based on M ekhilta in Parshat Bo. Providence and is also familar Why must we depart from this in- with the answer in 33: 19, "And I terpretation? shall be gracious to whom I shall Elias Munk show mercy." The selectivity of Downsview, Ontario God's providence has thus been well established ever since the days of the golden calf and it would RABBi GRANA TSTEIN REPLIES: seem unlikely that God had cho- sen a prophet who was not perfect- I cannot agree with Mr. -

The King Who Will Rule the World the Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A

David’s Heir – The King Who Will Rule the World The Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A. Nagasawa Last modified: September 24, 2009 Introduction: The Hero Among ‘the gifts of the Jews’ given to the rest of the world is a hope: A hope for a King who will rule the world with justice, mercy, and peace. Stories and legends from long ago seem to suggest that we are waiting for a special hero. However, it is the larger Jewish story that gives very specific meaning and shape to that hope. The theme of the Writings is the Heir of David, the King who will rule the world. This section of Scripture is very significant, especially taken all together as a whole. For example, not only is the Book of Psalms a personal favorite of many people for its emotional expression, it is a prophetic favorite of the New Testament. The Psalms, written long before Jesus, point to a King. The NT quotes Psalms 2, 16, and 110 (Psalm 110 is the most quoted chapter of the OT by the NT, more frequently cited than Isaiah 53) in very important places to assert that Jesus is the King of Israel and King of the world. The Book of Chronicles – the last book of the Writings – points to a King. He will come from the line of David, and he will rule the world. Who will that King be? What will his life be like? Will he usher in the life promised by God to Israel and the world? If so, how? And, what will he accomplish? How worldwide will his reign be? How will he defeat evil on God’s behalf? Those are the major questions and themes found in the Writings. -

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (And

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (and Danielic Literature) in the Early Church Wisdom and Apocalypticism Section SBL Annual Meeting in Washington, November 18-22, 2006 by Gerbern S. Oegema, McGill University 3520 University Street, Montreal, QC. Canada H3A 2A7 all rights reserved: for seminar use only. Any quotation from or reference to this paper should be made only with permission of author: [email protected] Abstract Whereas cosmogony has traditionally been seen as a topic dealt with primarily in wisdom literature, and eschatology, a field mostly focused upon in apocalyptic literature, the categorization of apocryphal and pseudepigraphic writings into sapiential, apocalyptic, and other genres has always been considered unsatisfactory. The reason is that most of the Pseudepigrapha share many elements of various genres and do not fit into only one genre. The Book of Daniel, counted among the Writings of the Hebrew Bible and among the Prophets in the Septuagint as well as in the Christian Old Testament, is such an example. Does it deal with an aspect of Israel’s origin and history, a topic dealt mostly dealt with in sapiential thinking, or only with its future, a question foremost asked with an eschatological or apocalyptic point of view? The answer is that the author sees part of the secrets of Israel’s future already revealed in its past. It is, therefore, in the process of investigating Israel’s history that apocalyptic eschatology and wisdom theology meet. This aspect is then stressed even more in the later reception history of the Book of Daniel as well as of writings ascribed to Daniel: if one wants to know something about Israel’s future in an ever-changing present situation, one needs to interpret the signs of the past. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

Proverbs Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker

PROVERBS 67 Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker Chapters 1-9 Introduction.Proverbs is generally regarded as the COMMENTARY book that best characterizes the Wisdom tradition. It is presented as a “guide for successful living.” Its PART 1: Ten wisdom instructions (Chapters 1-9) primary purpose is to teach wisdom. In chapters 1-9, we find a set of ten instructions, A “proverb” is a short saying that summarizes some aimed at persuading young minds about the power of truths about life. Knowing and practicing such truths wisdom. constitutes wisdom—the ability to navigate human relationships and realities. CHAPTER 1: Avoid the path of the wicked; Lady Wisdom speaks The Book of Proverbs takes its name from its first verse: “The proverbs of Solomon, the son of David.” “That men may appreciate wisdom and discipline, Solomon is not the author of this book which is a may understand words of intelligence; may receive compilation of smaller collections of sayings training in wise conduct….” (vv 2-3) gathered up over many centuries and finally edited around 500 B.C. “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge….” (v.7) In Proverbs we will find that certain themes or topics are dealt with several times, such as respect for Verses 1-7.In these verses, the sage or teacher sets parents and teachers, control of one’s tongue, down his goal: to instruct people in the ways of cautious trust of others, care in the selection of wisdom. friends, avoidance of fools and women with loose morals, practice of virtues such as humility, The ten instructions in chapters 1-9 are for those prudence, justice, temperance and obedience. -

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5Th, 2015 Text

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5th, 2015 Text: Proverbs 1:1-7 Background/Theme: The book of Proverbs was written mainly by Solomon (known as Israel’s wisest king) yet some of the later sections were written by men named Lemuel and Agur (See Prov. 1:1). It was written during Solomon’s reign (970-930 B.C.). Solomon asked God for wisdom to rule God’s nation and God granted it (1 Kings 3:6-14). Proverbs along with Job, Psalms, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon are known as the writings or “Wisdom Books” addressing practical living before God. The theme of Proverbs is wisdom (the skilled and right use of knowledge). The main purpose of this book is to teach wisdom to God’s people through the use of proverbs. The word Proverb means “to be like.” Therefore, Proverbs are short statements, which compare and contrast common, concrete images with life’s most profound truth. They are practical and point the way to godly character. These proverbs address subjects such as: life, family, friends, good judgment, and distinctions between the wise and foolish man. Proverbs is not a do-it-yourself success kit for the greedy but a guidebook for the godly. This starts with fearing the LORD. Memory Verse: Prov. 1:7 Outline: Ch 1-9-Solomon writes wisdom for younger people. Ch 10-24 - There is wisdom on various topics that apply to the average person. Ch 25-31 - Wisdom for leaders is provided. Tips for reading proverbs-Proverbs are statements of general truth and must not be taken as divine promises (Prov. -

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible The following are some excerpts from a fuller experience and reason. The means of acquiring introduction to the Wisdom books of the bible. (For wisdom are through study, instruction, discipline, the complete introduction, see Article 66 on my reflection, meditation and counsel. He who hates Commentaries on the Books of the Old Testament.) wisdom is called a fool, sinner, ignorant, proud, wicked, and senseless. The message of the Wisdom There are five books in the Old Testament called teachers can be summed up in the words of St. Paul: “Wisdom books”: Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, “What things are true, whatever honorable, whatever Ecclesiasticus and Wisdom. In Catholic Bibles, the just, whatever holy, whatever lovable, whatever of Song of Songs and Psalms are also grouped in the good repute, if there be any virtue, if anything worthy Wisdom books section. of praise, think upon these things. And what you have The reader who moves from the historical or learned and received and heard and seen in me, these prophetical books of the Bible into the Wisdom books things practice (Phil.4:8-9); whether you eat or drink, will find him/herself in a different world. While the or do anything else, do all for the glory of God” (1Cor. Wisdom books differ among themselves in both style 10:31). and subject matter, they have in common the following characteristics: The Catholic Bible – Personal Study Edition offers the following short description for each of the seven books 1. They show minimum interest in the great themes contained in the Wisdom section of Catholic Bibles. -

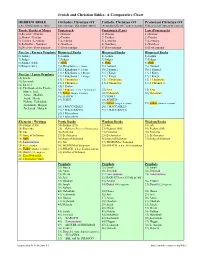

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

A Thematic Study of Doctrines on Death and Afterlife According to Targum Qohelet

A Thematic Study of Doctrines on Death and Afterlife according to Targum Qohelet By LAWRENCE RONALD LINCOLN DISSERTATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PHD in Ancient Cultures FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES PROMOTER: PROF JOHANN COOK April 2019 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This dissertation examined how the Targum radically transformed Qohelet’s pessimistic, secular and cynical views on the human condition by introducing a composite rabbinical theology throughout the translation with the purpose of refuting the futility of human existence and the finality of death. The Targum overturned the personal observations of Qohelet and in its place proposed a practical guide for the living according to the principles of rabbinic theological principles. While BibQoh provided few if any solutions for the many pitfalls and challenges of life and lacking any clear references to an eschatology, the Targum on the other hand promoted the promise of everlasting life as a model for a beatific eschatological future. The dissertation demonstrated how the targumist exploited a specific translation strategy to introduce rabbinic ideologies to present the targum as an alternative context to the ideologies of wisdom literature as presented in Biblical Qohelet. -

The Book of Enoch in the Light of the Qumran Wisdom Literature

CHAPTER FIVE THE BOOK OF ENOCH IN THE LIGHT OF THE QUMRAN WISDOM LITERATURE I The Book of Watchers is now regarded as the earliest apocalypse that we possess, and the Book of Enoch as a whole as a prime example of the apocalyptic genre, a major source for our understanding of apocalyp- ticism. The apocalyptic genre is, of course, traditionally regarded as representing a continuation of prophecy, and the Book of Enoch does make use of prophetic genres in a variety of ways. It is also of inter- est to note that the quotation of 1:9 in Jude 14–15 is introduced by the statement that Enoch “prophesied” about the heretics condemned by Jude, and that in Ethiopian tradition of a much later age Enoch is called the fi rst of the prophets. But in the Book of Enoch itself, Enoch is described as a scribe and a wise man, and his writings as the source of wisdom, and although the book cannot in any sense be regarded as a conventional wisdom book, this inevitably raises the question of the relationship of the book to ‘wisdom’ and the wisdom literature. Within the last decade Randall Argall and Ben Wright have attempted to answer this question by comparing 1 Enoch with Sirach. Thus in a recent monograph, 1 Enoch and Sirach: A Comparative Literary and Conceptual Analysis of the Themes of Revelation, Creation and Judgment, Argall argued that there are similarities in the way 1 Enoch and Sirach treat the themes of revelation, creation, and judgment, and “that their respective views were formulated, at least in part, over against one another.”1 Ben Wright has taken views like this further and has argued that Ben Sira actively took the side of the temple priests in polemical opposition against those, such as the authors of the Book of Watchers, who criticized them.2 He, like 1 Randall A. -

It Is Written Bible Guide

THE OLD TESTAMENT BOOK AUTHOR THEME KEY WORD KEY VERSE BOOKS OF THE LAW The Beginning of Man’s Sin and God’s Genesis Moses Beginning Genesis 17:7 Redemption Plan Exodus Moses God Redeems His Chosen People Deliverence Exodus 3:14 Leviticus Moses God Provides Access for Fellowship Holiness Lev 20:7-8 Numbers Moses God Instructs and Disciplines Unbelief Num 6:24-26 Deuteronomy Moses God Requires Obedience Remember Deut 6:4-5 BOOKS OF HISTORY Joshua Joshua God Fulfills His Promise of a Land Success Joshua 1:7 Judges Unknown God’s Mercy and Compassion History Judges 22:25 Ruth Unknown God’s Love Extended Redeemer Ruth 1:16 Samuel Prayer 1 Sam 15:22 1 & 2 Samuel God Chooses and Guides a King Unknown Consequences 2 Sam 7:11-13 Choices 1 Kings 18:21 1 & 2 Kings Unknown God Rules Israel Supreme 2 Kings 13:23 Sovereignty 1 Chr17:14 1 & 2 Chronicles Ezra God Preserves The Royal Seed Faithfulness 2 Chr 7:19-20 Ezra Ezra God Restores Israel Return Ezra 3:11-12 Nehemiah Nehemiah God Rebuilds Jerusalem Rebuilding Nehemiah 8:10 Esther Unknown God Protects Israel Deliverance Esther 4:14 BOOKS OF WISDOM Job Unknown God Tests Job Worship Job 19:25-26 David, Asaph, Solomon, Psalms God Receives Worship Praise Psalm 145:21 Moses, sons of Korah Solomon, Agur, Proverbs God Teaches Wisdom Fear the Lord Prov 3:5-6 Lemuel Ecclesiastes Solomon God is Infinite; Man is Finite Meaningless Ecc 12:13-14 Song of Song of Solomon God Blesses Human Love Love’s Mysteries Solomon Solomon 8:7 BOOK AUTHOR THEME KEY WORD KEY VERSE BOOKS OF PROPHECY Isaiah Isaiah God’s Great Salvation