The Aesthetics of Actor-Character Race Matching in Film Fictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012

26901 Agoura Road, Suite 150, Calabasas Hills, CA 91301 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012 LOT ITEM PRICE 4 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $275 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE”. 5 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $200 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE” FIGHTING BAD GUYS. 6 X-MEN “PHOENIX SAGA (PART 3) CRY OF THE BANSHEE”, ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL $100 AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “ERIK THE REDD”. 8 X-MEN OVERSIZED ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $150 “GAMBIT”, “ROGUE”, “PROFESSOR X” & “JUBILEE”. 9 X-MEN “WEAPON X, LIES, AND VIDEOTAPE”, (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND $225 BACKGROUND FEATURING “WOLVERINE” IN WEAPON X CHAMBER. 16 X-MEN ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “BEAST”. $100 17 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “NASTY BOYS”, $100 “SLAB” & “HAIRBAG”. 21 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”. $100 23 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND (2) SKETCHES FEATURING CYCLOPS’ $125 VISION OF JEAN GREY AS “PHOENIX”. 24 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $150 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 25 X-MEN (9) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND PAN BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $175 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 27 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”, $100 “ROGUE” AND “DARKSTAR” FLYING. 31 X-MEN THE ANIMATED SERIES, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $100 FEATURING “PROFESSOR X” AND “2 SENTINELS”. 35 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION PAN CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $100 “WOLVERINE”, “ROGUE” AND “NIGHTCRAWLER”. -

Vulpes Vulpes) Evolved Throughout History?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses Environmental Studies Program 2020 TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY? Abigail Misfeldt University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses Part of the Environmental Education Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Disclaimer: The following thesis was produced in the Environmental Studies Program as a student senior capstone project. Misfeldt, Abigail, "TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY?" (2020). Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses. 283. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses/283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY? By Abigail Misfeldt A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The University of Nebraska-Lincoln In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Science Major: Environmental Studies Under the Supervision of Dr. David Gosselin Lincoln, Nebraska November 2020 Abstract Red foxes are one of the few creatures able to adapt to living alongside humans as we have evolved. All humans and wildlife have some id of relationship, be it a friendly one or one of mutual hatred, or simply a neutral one. Through a systematic research review of legends, books, and journal articles, I mapped how humans and foxes have evolved together. -

NAC 2018 Final Eligible List.Xlsx

American Kennel Club 2018 National Agility Championship FINAL List of Eligible Dogs Breed Primary Owner Dog's Registered Name Affenpinscher Sharon Rafferty CH Ferlin's Black Jaguar MX MXB MXJ MJB CAX CGCA CGCU Airedale Terrier Deanna Corboy‐Lulik MACH3 Connemara's Sense Of Adventure SH MXC PAD MJC MFS TQX T2B3 Airedale Terrier Deanna Corboy‐Lulik MACH4 Connemara's Parteigh Like A Rock Star BN RE SH MXC3 MJG3 MXP MJP MFC TQX T2B3 Airedale Terrier Rhonda Walker MACH2 Connemara's Hunt For The Party MXC MJB2 OF T2B Airedale Terrier Rhonda Walker MACH2 Eclipse Journey Ripples Thru Time MXG MJC2 OF T2B Airedale Terrier William Fridrych MACH12 Connemara's Nothin But Aire MXS4 MJG4 Airedale Terrier William Fridrych MACH2 Connemara's Talkin To You MXC MJG MXF T2B2 Alaskan Malamute Cathie Reinhard PACH3 Ixa's Mesmerizing Miss Mickey UD BN AX AXJ MXP15 MXPS2 MJP13 MJPB2 PAX3 NF MFPC TQXP T2BP Alaskan Malamute James Alger PACH2 Lone Wolf Little Man Avery BN MXP9 MXPG MJP8 MJPG PAX2 XFP THDX CGC TKA Alaskan Malamute Raissa Hinman MACH6 Arcticdawn's Boots R' Made For Mushin' UDX7 OM9 RE MXC2 MJB3 MFB TQX T2B All American Dog Adrienne McLean MACH4 Jinx Falkenburg McLean MXC MJC T2B All American Dog ALISON DAY MACH3 Day's Katie MXG MJG MXF T2B3 TKA All American Dog Alison Hall MACH2 Nounours Lionheart Wynne MXS MJG All American Dog ALLISON MOONEY Jager Meister MX MXB MXJ MJB OF T2B All American Dog Alyson Deine‐Schartz H.E.L.P.Er. RE AX MXJ OF CGCA All American Dog AMY ANDERSON MACH Anderson's Lottie RE MXB MJB MXP MJP OF T2B All American Dog AMY GLOMAN -

The Raunchy Splendor of Mike Kuchar's Dirty Pictures

MIKE KUCHAR ART The Raunchy Splendor of Mike Kuchar’s Dirty Pictures by JENNIFER KRASINSKI SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 “Blue Eyes” (1980–2000s) MIKE KUCHAR/ANTON KERN GALLERY/GHEBALY GALLERY AS AN ILLUSTRATOR, MY AIM IS TO AMUSE THE EYE AND SPARK IMAGINATION, wrote the great American artist and filmmaker Mike Kuchar in Primal Male, a book of his collected drawings. TO CREATE TITILLATING SCENES THAT REFRESH THE SOUL… AND PUT A BIT MORE “FUN” TO VIEWING PICTURES — and that he has done for over five decades. “Drawings by Mike!” is an exhibition of erotic illustrations at Anton Kern Gallery, one of the fall season’s great feasts for the eye and a welcome homecoming for one of New York’s most treasured prodigal sons. Sympathy for the devil: Mike Kuchar’s “Rescued!” (2017) MIKE KUCHAR/ANTON KERN GALLERY As boys growing up in the Bronx, Mike and his twin brother — the late, equally great film and video artist George (1942–2011) — loved to spend their weekends at the movies, watching everything from newsreels to B films to blockbusters, their young minds roused by all the thrills that Hollywood had to offer: romance, drama, action, science fiction, terror, suspense. As George remembered in their 1997 Reflecons From a Cinemac Cesspool, a memoir-cum–manual for aspiring filmmakers: “On the screen there would always be a wonderful tapestry of big people and they seemed so wild and crazy….e women wantonly lifted up their skirts to adjust garter-belts and men in pin-striped suits appeared from behind shadowed décor to suck and chew on Technicolor lips.” For the Kuchars, as for gay male contemporaries like Andy Warhol and Jack Smith, the movie theater was a temple for erotics both expressed and repressed, projected and appropriated, homo and hetero, all whirled together on the silver screen. -

Roger Dunsmore Came to the University of Montana in 1963 As a Freshman Composition Instructor in the English Department

January 30 Introduction to the Series Roger Dunsmore Bio: Roger Dunsmore came to the University of Montana in 1963 as a freshman composition instructor in the English Department. In 1964 he also began to teach half- time in the Humanities Program. He taught his first course in American Indian Literature, Indian Autobiographies, in 1969. In 1971 he was an originating member of the faculty group that formed the Round River Experiment in Environmental Education (1971- 74) and has taught in UM’s Wilderness and Civilization Program since 1976. He received his MFA in Creative Writing (poetry) in 1971 and his first volume of poetry.On The Road To Sleeping ChildHotsprings was published that same year. (Revised edition, 1977.) Lazslo Toth, a documentary poem on the smashing of Michelangelo’s Pieta was published in 1979. His second full length volume of poems,Bloodhouse, 1987, was selected by the Yellowstone Art Center, Billings, MX for their Regional Writer’s Project.. The title poem of his chapbook.The Sharp-Shinned Hawk, 1987, was nominated by the Koyukon writer, Mary TallMountain for a Pushcat Prize. He retired from full-time teaching after twenty-five years, in 1988, but continues at UM under a one- third time retiree option. During the 1988-89 academic year he was Humanities Scholar in Residence for the Arizona Humanities Council, training teachers at a large Indian high school on the Navajo Reservation. A chapbook of his reading at the International Wildlife Film Festival, The Bear Remembers, was published in 1990. Spring semester, 1991, (and again in the fall semester, 1997) he taught modern American Literature as UM’s Exchange Fellow with Shanghai International Studies University in mainland China. -

Big Country 1958 Imdb

Big country 1958 imdb Romance · A New Englander arrives in the Old West, where he becomes embroiled in a feud between two families over a valuable patch of land. In The Big Country Gregory Peck plays a seafaring man who heads west to marry Carroll Baker, the daughter of rancher Charles Bickford. The Big Country is a American epic Western film directed by William Wyler and starring . External links[edit]. The Big Country on IMDb · The Big Country at the TCM Movie Database · The Big Country at AllMovie Plot · Cast · Reception. Directed by William Wyler. With Gregory Peck, Jean Simmons, Carroll Baker, Charlton Heston. A New Englander arrives in the Old West, where he becomes. Retired, wealthy sea Captain Jame McKay arrives in the vast expanse of the West to marry fiancée Pat Terrill. McKay is a man whose values and approach to life. This Pin was discovered by Günal Mutlu. Discover (and save!) your own Pins on Pinterest. The Big Country (). mijn stem. 3, stemmen. Verenigde Staten Western / Romantiek minuten. geregisseerd door William Wyler. This Pin was discovered by Liz Horne. Discover (and save) your own Pins on Pinterest. The Big Country () Movie, Subtitles, Reviews on Subtitles , The Big Country - Reviews, Horoscopes & Charts free online. The Big Country summary of box office results, charts and release information and related links. : The Big Country: Gregory Peck, Jean Simmons, Carroll Baker, Charlton Heston, Burl Ives, Charles Learn more about "The Big Country" on IMDb. Watch online The Big Country full with English subtitle. Watch online free The Big Country, Charlton Heston, Gregory Peck, Burl Ives, Chuck Connors, Carroll Baker, Jean Simmons, Charles Bickford, Alfonso Bedoya. -

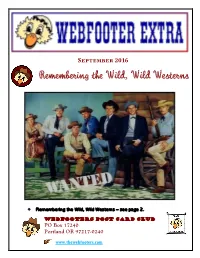

The Webfooter

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

Mountain Men on Film Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 1-1-2016 Mountain Men on Film Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Citation Information Hall, Kenneth Estes. 2016. Mountain Men on Film. Studies in the Western. Vol.24 97-119. http://www.westernforschungszentrum.de/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mountain Men on Film Copyright Statement This document was published with permission from the journal. It was originally published in the Studies in the Western. This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/596 Peter Bischoff 53 Warshow, Robert. "Movie Chronicle: The Western." Partisan Re- view, 21 (1954), 190-203. (Quoted from reference number 33) Mountain Men on Film 54 Webb, Walter Prescott. The Great Plains. Boston: Ginn and Kenneth E. Hall Company, 1931. 55 West, Ray B. , Jr., ed. Rocky Mountain Reader. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1946. 56 Westbrook, Max. "The Authentic Western." Western American Literatu,e, 13 (Fall 1978), 213-25. 57 The Western Literature Association (sponsored by). A Literary History of the American West. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1987. -

Wolverine Vs. Sabretooth Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WOLVERINE VS. SABRETOOTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Disney Book Group,Clarissa Wong | 24 pages | 05 Feb 2013 | Marvel Press | 9781423172895 | English | New York, United States Wolverine vs. Sabretooth PDF Book Victor runs off during the fight, wishing Rose "good luck in hell". Add the first question. Both characters have been horribly mismanaged over the past few years, but Sabretooth should win the majority of these fights. This includes the ability to see objects with greater clarity and at much greater distances than an ordinary human. Sabretooth, not believing him, dares Wolverine to do it. Creed sets a trap for Logan before heading to his meeting, but it fails causing the two to battle. A wolverine -- the animal -- is a large carnivore that looks like a small bear. And then for whatever reason we didn't do it. It also indicates that his fighting speed is his most enhanced skill. His rampage is brought to an end when Wolverine interrupts him and the two battle to a stalemate, at one point knocking one another out. As we have seen every time a battle between Logan and Victor happens, Sabretooth always has the upper hand, but Wolverine turns out to win at the end. But, the brutal moment shows how Wolverine exhausted all of his options in dealing with Sabretooth and decided the best way to stop him was to kill him. His size and strength, added with his healing factor and adamantuim tipped clawz and his Special Forces training. Back to School Picks. In , Creed using the alias Sabretooth works as a mercenary assassin in Saigon. -

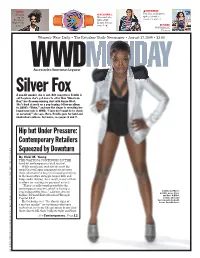

Silver Fox a One-Hit Wonder, She Is Not

Page 1 Monday RETAIL: ▲ INNERWEAR: Gearing ACCESSORIES: Vendors and buyers up for Movado links upbeat about a Fashion’s with artist recovery, page 8. Night Out, Kenny Scharf, ▲ page 9. INSIDE: page 3. ▲ WWDMAGIC Preview Women’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • August 17, 2009 • $3.00 WWDAccessories/Innerwear/Legwear MONDAY Silver Fox A one-hit wonder, she is not. Brit songstress Estelle is out to prove she’s got more to offer than “American Boy,” her Grammy-winning duet with Kanye West. She’s hard at work on a pop-leaning follow-up album to 2008’s “Shine,” and now the singer is revealing her brand new look to WWD. “I just don’t want to be stuck or corseted,” she says. Here, Estelle goes for bold and unabashed sexiness. For more, see pages 6 and 7. Hip but Under Pressure: Contemporary Retailers Squeezed by Downturn By Vicki M. Young THE WAITING CONTINUES IN THE hard-hit contemporary retail market. While merchants wait for the next big trend that will spur consumers to get over their reluctance to buy, the finance executives in the back office struggle to pay bills and keep credit flowing. As a result, many of their vendors are waiting for payment as well. “This is a really tough period for the contemporary market, which is having a Camilla and Marc’s supercompetitive time,” said investment metallic weave blazer banker Richard Kestenbaum of Triangle and Sass & Bide’s Capital LLC. acetate, nylon and Lycra spandex bodysuit. Kestenbaum sees “the classic signs of Cesare Paciotti shoes. -

1985 Downtown Newhall Western Walk of Fame

WELCOME to the 5th Annual westernWalk of fame MICHAEL D. ANTONOVICH 5TH DISTRICT supervisor - LOS ANGELES COUNTY 1985 WALK OF FAME HONORARY CHAIRMAN - - NEWHALL'S WESTERN WALK OF FAME HOW IT ALL BEGAN----- The original idea for a Western Walk of Fame came as a suggestion from Milt Diamond, pioneer, western clothing retailer who was President of the Newhall Merchant's Association in 1976. He continued his pursuit to the Santa Clarita Valley Chamber of Commerce. In 1981, Mr. Diamond realized his dream come true when the first "Western Walk of Fame" honored Wm. s. Hart, Tom Mix and Gene Autry as the first recipients of the coveted award. The entire program was concieved as a tribute to the western artists who contributed to the Santa Clarita Valley's and nation ' s heritage since 1876 when the town of Newhall was founded. Now , in its fifth year, it has given bronze immor tality to well known western greats Gene Autry, Wm. Hart, Torn Mix, Tex Ritter, Rex Allen, Eddie Dean, Pat Buttram, Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, Andy Jauregui, Tex Williams, Claude Akins, John Wayne, Clayton Moore, Robert Conrad, Dennis Weaver and Clint Walker. And, of course, on August 24, 1985 stars Iron Eyes Cody, Monte Hale and Chuck Connors will be added to prestigious path of bronze and terrazzo tile "saddle type" plaques that can be viewed on San Fernando Road (5th Street to 9th Street) in downtown Newhall. Congratulations Architects for Offices at Stoney Creek WELCOME TO THE FIFTH ANNUAL WESTERN WALK OF FAME SPECIAL ENTERTAINMENT EV ENTS "The Town Rowdies " Band "Badland Buckaroos Band 11 "Jeff Connors Band" a nd t he "Wind River Cloggers" Comedian s Pat Buttram and Don Hinson Western Walk of Fame Awards program with Master of Ceremonies Johnny Grant and Cliffie Stone Plus -- Many Guest Celebrities Opportunity Drawings Watering Hole Refreshment Centers Dancing until Midnight REACH FOR THE SKY! YOU 'RE IN DAILY NEWS COUNTRY. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Bob

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Bob Burke Autographs of Western Stars Collection Autographed Images and Ephemera Box 1 Folder: 1. Roy Acuff Black-and-white photograph of singer Roy Acuff with his separate autograph. 2. Claude Akins Signed black-and-white photograph of actor Claude Akins. 3. Alabama Signed color photograph of musical group Alabama. 4. Gary Allan Signed color photograph of musician Gary Allan. 5. Rex Allen Signed black-and-white photograph of singer, actor, and songwriter Rex Allen. 6. June Allyson Signed black-and-white photograph of actor June Allyson. 7. Michael Ansara Black-and-white photograph of actor Michael Ansara, matted with his autograph. 8. Apple Dumpling Gang Black-and-white signed photograph of Tim Conway, Don Knotts, and Harry Morgan in The Apple Dumpling Gang, 1975. 9. James Arness Black-and-white signed photograph of actor James Arness. 10. Eddy Arnold Signed black-and-white photograph of singer Eddy Arnold. 11. Gene Autry Movie Mirror, Vol. 17, No. 5, October 1940. Cover signed by Gene Autry. Includes an article on the Autry movie Carolina Moon. 12. Lauren Bacall Black-and-white signed photograph of Lauren Bacall from Bright Leaf, 1950. 13. Ken Berry Black-and-white photograph of actor Ken Berry, matted with his autograph. 14. Clint Black Signed black-and-white photograph of singer Clint Black. 15. Amanda Blake Signed black-and-white photograph of actor Amanda Blake. 16. Claire Bloom Black-and-white promotional photograph for A Doll’s House, 1973. Signed by Claire Bloom. 17. Ann Blyth Signed black-and-white photograph of actor and singer Ann Blyth.