Now: an Exploration of Contemporary Dutch Utopian Thought and Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Course Outlines

Page | 1 Page | 2 Academic Programs Offered 1. BS Graphic Design 2. BS Textile Design 3. BS Fine Arts 4. BS Interior Design 5. MA Fine Arts 6. Diploma in Fashion Design 7. Diploma in Painting BS Graphic Design Eligibility: At least 45% marks in intermediate (FA/FSC) or equivalent, the candidate has to pass with 45% passing marks. Duration: 04 Year Program (08 Semesters) Degree Requirements: 139 Credit Hours Semester-1 Course Code Course Title Credit Hours URCE- 5101 Grammar 3(3+0) URCP- 5106 Pakistan Studies 2(2+0) GRAD-5101 Calligraphy-I 3(0+3) GRAD-5102 Basic Design-I 3(0+3) GRAD-5103 Drawing-I 3(0+3) URCI-5109 Introduction to Information & Communication 3(2+1) Technologies Semester-2 URCE- 5102 Language Comprehension & Presentation Skills 3(3+0) URCI- 5105 Islamic Studies 2(2+0) GRAD-5105 Calligraphy-II 3(0+3) GRAD-5106 Basic Design-II 3(0+3) URCM-5107 Mathematics (Geometry and Drafting) 3(3+0) GRAD-5107 Drawing-II 3(0+3) Semester-3 URCE- 5103 Academic Writing 3(3+0) GRAD-5108 History of Art 3(3+0) GRAD-5109 Drawing-III 3(0+3) GRAD-5110 Graphic Design-I 3(0+3) GRAD-5111 Photography-I 3(0+3) GRAD-5112 Communication Design 3(0+3) URCC-5110 Citizenship Education and Community Engagement 3(1+2) Semester-4 URCE- 5104 Introduction to English Literature 3(3+0) Page | 3 GRAD-5113 Fundamental of Typography 2(0+2) GRAD-5114 History of Graphic Design-I 3(3+0) GRAD-5115 Graphic Design-II 3(0+3) GRAD-5116 Photography-II 3(0+3) GRAD-5117 Techniques of Printing 2(1+1) Semester-5 GRAD-6118 History of Graphic Design-II 3(3+0) GRAD-6119 Graphic Design-III -

Set'18 Ars Ludens – Arte, Jogo E Lúdico

ISSN 2183–6973 REVISTA DE CIÊNCIAS DA ARTE N.º6 | SET'18 ARS LUDENS – ARTE, JOGO E LÚDICO ISSN 2183–6973 REVISTA DE CIÊNCIAS DA ARTE N.º6 | SET'18 ARS LUDENS – ARTE, JOGO E LÚDICO Convocarte – Revista de Versão digital gratuita Ciências da Arte convocarte.belasartes.ulisboa.pt Revista Internacional Digital com Comissão Científica Editorial e Revisão Versão impressa de Pares loja.belasartes.ulisboa.pt N.º6, Setembro de 2018 Gabinete de Comunicação e Imagem Tema do Dossier Temático Isabel Nunes e Teresa Sabido Ars Ludens – Arte, Jogo e Lúdico: A Arte (+351) 213 252 108 como Jogo? / L'art comme jeu? / Art as [email protected] play, art as game? Desenho Gráfico Ideia e Coordenação Científica Geral João Capitolino Fernando Rosa Dias Apoio à edição digital Coordenação Científica do Dossier Ricardo Vilhena, Paulo Santos e Temático N.º 6 e 7 − Ars Ludens – Arte, Tomás Gouveia (FBAUL) Jogo e Lúdico Pascal Krajewski Créditos capa N.º 6 Benedetto Buffalino Periodicidade Créditos capa dossier temático N.º 6 Semestral Honoré Daumier, Les Joueurs d’échecs (1863), Paris, Petit Palais Edição FBAUL – CIEBA Produção Gráfica (Secção Francisco d´Holanda e Área de inPrintout – Fluxo de Produçao Gráfica Ciências da Arte e do Património) Tiragem Depósito Legal 150 exemplares 418146/16 Propriedade e Serviços ISSN Faculdade de Belas Artes da 2183–6973 Universidade de Lisboa (FBAUL) Centro de Investigação e Estudos em e-ISSN (Em linha) Belas Artes (CIEBA), secção Francisco 2183–6981 d’Holanda (FH), Área de Ciências da Arte e do Património (gabinete 4.23) Plataforma digital de edição e contactos Largo da Academia Nacional de Belas convocarte.belasartes.ulisboa.pt Artes, 1249-058 Lisboa [email protected] (+351) 213 252 100 belasartes.ulisboa.pt Conselho Científico Editorial e Pares Membros Honorários do Conselho Académicos − N. -

Unification of Art Theories (Uat) - a Long Manifesto

UNIFICATION OF ART THEORIES (UAT) - A LONG MANIFESTO - by FLORENTIN SMARANDACHE ABSTRACT. “Outer-Art” is a movement set up as a protest against, or to ridicule, the random modern art which states that everything is… art! It was initiated by Florentin Smarandache, in 1990s, who ironically called for an upside-down artwork: to do art in a way it is not supposed to be done, i.e. to make art as ugly, as silly, as wrong as possible, and generally as impossible as possible! He published three such (outer-)albums, the second one called “oUTER-aRT, the Worst Possible Art in the World!” (2002). FLORENTIN SMARANDACHE Excerpts from his (outer-)art theory: <The way of how not to write, which is an emblem of paradoxism, was later on extended to the way of how not to paint, how not to design, how to not sculpture, until the way of how not to act, or how not to sing, or how not to perform on the stage – thus: all reversed. Only negative adjectives are cumulated in the outer- art: utterly awful and uninteresting art; disgusting, execrable, failure art; garbage paintings: from crumpled, dirty, smeared, torn, ragged paper; using anti-colors and a-colors; naturalist paintings: from wick, spit, urine, feces, any waste matter; misjudged art; self-discredited, ignored, lousy, stinky, hooted, chaotic, vain, lazy, inadequate art (I had once misspelled 'rat' instead of 'art'); obscure, unremarkable, syncopal art; para-art; deriding art expressing inanity and emptiness; strange, stupid, nerd art, in-deterministic, incoherent, dull, uneven art... as made by any monkey!… the worse the better!> 2 A MANIFESTO AND ANTI-MANIFESTO FOR OUTER-ART I was curious to learn new ideas/ schools /styles/ techniques/ movements in arts and letters. -

Pentru Ce Împrumută Galaţiul 185 De Milioane De Lei

VINERI . 19 IULIE 2019 WWW.VIATA-LIBERA.RO ZIUA AVIAŢIEI, PROBLEME SRBTORIT LA UNITED, LA TECUCI DIN CAUZA FRF ZBOR. Sâmbătă, 20 iulie, FUTSAL. Vicecampioana United la Muzeul Aeronauticii Moldovei Galaţi se confruntă cu probleme de lot, din Tecuci se va sărbători Ziua în urma unor schimbări de regulament Aviaţiei Române, cu zboruri decise de Comitetul Executiv al Federaţiei demonstrative, prelegeri şi vizite la RoRomânemâne ddee FoFotbal.tbal. > pag.pag 007 muzeu. > pag. 09 l COTIDIAN INDEPENDENT / GALAŢI, ROMÂNIA / ANUL XXX, NR. 9065 / 20 PAGINI / 20 PAGINI SUPLIMENT TV GRATUIT / 2 LEI PRIMĂRIA STINGE DOUĂ CREDITE I CONTRACTEAZĂ ALTE DOUĂ > EVENIMENT/055 Pentru ce LA ZI cat împrumută V.L.fi Galaţiul ig s-a cali Ţ 185 Patricia de milioane succes în sferturile BRD Bucharest Open de lei 07 PentruPentru achiziachiziţiaia a 4040 dede autobuzeautobuze nonoi,i, Primăria a făcut un credit de 100 de milioane de lei, un alt împrumut, de 85 de meteo milioane de lei, fi ind destinatt refi nanţării altor două creditee mai vechi. A. Melinte 30˚ u foto Bogdan Codrescu Variabil Sistemul asigurărilor de sănătate, valuta BNR blocat de trei săptămâni €4,73 REMUS BASALIC le cu Casa Naţională de Asigurări Astfel, dacă îi dau o reţetă sau [email protected] de Sănătate (CNAS). Ieri, CNAS a un bilet de trimitere unei persoa- făcut o tentativă de repornire ne neasigurate, respectivul servi- GRATUIT $4,21 Încă de la sfârşitul lunii iunie, a programului, însă sistemul a ciu îmi va fi apoi imputat mie. cu „Viaţa liberă” Cursul de schimb valutar sistemul cardului de sănătate a rămas în continuare blocat. -

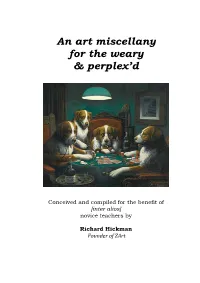

An Art Miscellany for the Weary & Perplex'd. Corsham

An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d Conceived and compiled for the benefit of [inter alios] novice teachers by Richard Hickman Founder of ZArt ii For Anastasia, Alexi.... and Max Cover: Poker Game Oil on canvas 61cm X 86cm Cassius Marcellus Coolidge (1894) Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/] Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue. Acrylic on board 60cm X 90cm Richard Hickman (1994) [From the collection of Susan Hickman Pinder] iii An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d First published by NSEAD [www.nsead.org] ISBN: 978-0-904684-34-6 This edition published by Barking Publications, Midsummer Common, Cambridge. © Richard Hickman 2018 iv Contents Acknowledgements vi Preface vii Part I: Hickman's Art Miscellany Introductory notes on the nature of art 1 DAMP HEMs 3 Notes on some styles of western art 8 Glossary of art-related terms 22 Money issues 45 Miscellaneous art facts 48 Looking at art objects 53 Studio techniques, materials and media 55 Hints for the traveller 65 Colours, countries, cultures and contexts 67 Colours used by artists 75 Art movements and periods 91 Recent art movements 94 World cultures having distinctive art forms 96 List of metaphorical and descriptive words 106 Part II: Art, creativity, & education: a canine perspective Introductory remarks 114 The nature of art 112 Creativity (1) 117 Art and the arts 134 Education Issues pertaining to classification 140 Creativity (2) 144 Culture 149 Selected aphorisms from Max 'the visionary' dog 156 Part III: Concluding observations The tail end 157 Bibliography 159 Appendix I 164 v Illustrations Cover: Poker Game, Cassius Coolidge (1894) Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue, Richard Hickman (1994) ii The Haywain, John Constable (1821) 3 Vagveg, Tabitha Millett (2013) 5 Series 1, No. -

Sounds of Alter-Destiny and Ikonoklast Panzerist Fabulations

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Sounds of Alter-destiny and Ikonoklast Panzerist Fabulations Mette Christiansen The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3401 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOUNDS OF ALTER-DESTINY AND IKONOKLAST PANZERIST FABULATIONS by METTE CHRISTIANSEN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 METTE CHRISTIANSEN All Rights Reserved ii SOUNDS OF ALTER-DESTINY AND IKONOKLAST PANZERIST FABULATIONS by Mette Christiansen This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date Susan Buck-Morss Thesis Advisor Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Sounds of Alter-destiny and Ikonoklast Panzerist Fabulations by Mette Christiansen Advisor: Susan Buck-Morss This study is a multifaceted attempt to complicate ideas about study, to think about the critical potential and social implications of certain kinds of stories, and how we might effectively disrupt and reinvent notions and techniques of critique and resistance in the names of hope and social transformation. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

2. Declarations of Conflict 3. Adoption of the Minutes

KK/ Windsor, Ontario October 11 , 2016 A meeting of the Community Public Art Advisory Committee is held this day commencing at 3:00 o'clock p.m. in the Walkerville Meeting Room, 3 floor, City Hall, there being present the following members: Leisha Nazarewich, Chairperson Councillor Rino Bortolin Julie Butler Dr. Brian Brown Therese Hounsell Recirets received from: Nadja Pelkey Also present are the followina resource personnel: Cathy Masterson, Manager of Cultural Affairs Jan Wilson, Executive Director, Recreation and Culture Karen Kadour, Committee Coordinator 1. CALL TO ORDER The Chair calls the meeting to order at 3:00 o'clock p.m. and the Committee considers the Agenda being Schedule "A" attached hereto, matters which are dealt with as follows: 2. DECLARATIONS OF CONFLICT None disclosed. 3. ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES Moved by Councillor Bortolin, seconded by T. Hounsell, That the minutes of the Community Public Art Advisory Committee of its meeting held July 19, 2016 BE ADOPTED as presented. Carried. 4.0 Community Public Art Advisory Committee October 11, 2016 Meeting IVIinutes 4. BUSINESS ITEMS 4.1 Potential Sites for Public Art The document entitled "Potential sites for opportunities to create and install public art" provided by the Manager of Cultural Affairs is distributed and attached as Appendix "A". C. Masterson provides an overview of the "Our Space 2016 Program" as follows: • Our Space is about creating accessibility that allows peoples' creativity to emerge and tell the Windsor story to the world. • The program will enhance and transform our Windsor Sculpture Park through partnership projects that celebrate and explore identify, develop community connections and sense of place through organizing creative opportunities. -

Albert Einstein .Welcome!

“Creativity is more important than knowledge” - Albert Einstein .Welcome! The High School Art Classes are educational experiences centered around creativity in a structured, but fun and enjoyable atmosphere. They are designed for all students, not just the “naturally talented artist”. Don’t worry about it if you can’t draw or paint - that is why you are taking this class - to learn these skills. The following handbook for the art room is a policy/procedure guide for students to reference. This book is designed to help all students achieve their greatest potential in the art program by having a smooth and efficient running classroom. With this in mind, clear policies and procedures need to be set forth that affect the student, the class environment, fellow peers, the instructor, and the safety of all. If there are questions about the information set forth, please feel free to ask any time. Logistics POLICIES • Appropriate behavior is expected. School rules and policies are upheld. Simply use your best judgment. • Consequences are as stated in school policy (may include coming in for activity period, staying after school, detention, etc.). • Promote an environment which ensures a smooth running and enjoyable educational experience. In addition to the standard set of school rules, there are 6 additional general rules in the art room: 1) “Do those things which support your learning and the learning of others” - use your best judgment 2) Everyone’s ideas are valued - no one or their ideas are to be put down or made fun of. You must feel comfortable taking chances and exploring artistic ideas in an inviting atmosphere. -

Unification of Art Theories (UAT)

UNIFICATION OF ART THEORIES (UAT) Mail oUTER-aRT 2007 FLORENTIN $MARANDACHE, Ph. D. Associate Professor Math & Science Department Chair University of New Mexico 200 College Road Gallup, NM 87301, USA [email protected] http://www.gallup.unm.edu/~smarandache/a/oUTER-aRT.htm Unification of Art Theories (UAT) =composed, found, changed, modified, altered, graffiti, polyvalent art= Unification of Art Theories (UAT) considers that every artist should employ - in producing an artwork – ideas, theories, styles, techniques and procedures of making art barrowed from various artists, teachers, schools of art, movements throughout history, but combined with new ones invented, or adopted from any knowledge field (science in special, literature, etc.), by the artist himself. The artist can use a multi-structure and multi-space. The distinction between Eclecticism and Unification of Art Theories (UAT) is that Eclecticism supposed to select among the previous schools and teachers and procedures - while UAT requires not only selecting but also to invent, or adopt from other (non-artistic) fields, new procedures. In this way UAT pushes forward the art development. Also, UAT has now a larger artistic database to choose from, than the 16th century Eclecticism, since new movements, art schools, styles, ideas, procedures of making art have been accumulated in the main time. Like a guide, UAT database should periodically be updated, changed, enlarged with new invented or adopted-from-any-field ideas, styles, art schools, movements, experimentation techniques, artists. It is an open increasing essay to include everything that has been done throughout history. This book presents a short panorama of commented art theories, together with experimental digital images using adopted techniques from various fields, in order to inspire the actual artists to choose from, and also to invent or adopt new procedures in producing their artworks. -

The 50 M Ost Influential Street Artists Today

influential today artists street The 50 most most 50 The Street art today 2 influential today artists street The 50 most most 50 The Street art 2 Bjørn todayVan Poucke THE HYPER-GLOBALISATION of the world in the 21st century has resulted in dynamics and trends that are hard to comprehend and cate- gorise using existing tools and methods. Whether we’re talking politics, economy, or culture, the transglobal mixing and merging – spiced up with the virtual allure of social media – has created hybrids which are regularly comprised of variety, sometimes incorporating opposing elements from different origins. In a converged world, everything has become a hard-to-read mishmash of stuff which some- times just doesn’t make sense any more. Highly noticeable, relatable, and ultimately hyper-likable, street art has not been spared these developments. Just like other forms of urban culture such as music or skate- boarding, the mainstream pretty much lost its well-calculated mind over these forms of youth culture expression. Seeing its immeasurable value as part of gentrification processes world- wide, borrowing elements to build their own credibility, or plainly (ab)using it for marketing INTRODUCTION or branding purposes, we’ve witnessed the creation of a monster in the recent years. But this isn’t the first time that things are taking such turn, as similar scenarios happened to other rebellious-minded movements – and most of It feels like them are still alive and kicking. And in all hon- esty, it feels like the peak of street art’s identity the peak of crisis is finally behind us and we’re witnessing the re-birth of a new, reinvented scene. -

The 50 M Ost Influential Street Artists Today

Street art The 50 most influential street artists today today Street art The 50 most influential street artists today today fore- Martyn Reed, wordfounder, director and curator of Norway's international contemporary My personal relationship to art, and in street and urban art festival Nuart particular subcultural art, is a typical ‘from rags to polyester’ story. An artless childhood D R steeped in poverty, deprivation, bad WO schooling, domestic violence and urban blight. re For most, the light at the end of the tunnel O F being nothing more than a miner’s lamp at the local colliery, the predominant industry in the industrial North of England at the time being mining – or for the younger ones, of which I was one, raised on dilapidated council estates, a life of vandalism, violence and petty crime. Graffiti was to come a short time later, and anyone too young for punk, with more than a passing interest in drawing, other than on their schoolbag, would be swept along in this Creativity, revolutionary new youth culture. born from Most communities ravaged by government neglect and a poverty of attention, both a lack of public and domestic, contain the seeds of a subculture – they just need adequate water. attention or Ironically, the water that nurtured the seed of the Nuart Festival was fire. Creativity, as an escape born from a lack of attention or as an escape from an oppressive reality, will always find an from an outlet, and the more it is genuinely needed, as a necessity for survival, the more authentic oppressive it will be.