Resources for School Change I: a Manual on Issues and Programs In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 1:99-Cv-02496-GK Document 6095 Filed 06/02/14 Page 1 of 27

Case 1:99-cv-02496-GK Document 6095 Filed 06/02/14 Page 1 of 27 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) Civil Action No. 99-CV -2496 (GK) ) Next scheduled court appearance: and ) NONE ) TOBACCO-FREE KIDS ) ACTION FUND, et al. ) ) Plaintiff-Intervenors ) ) V. ) ) PHILIP MORRIS USA INC., et al., ) ) Defendants. ) I -Remand CONSENT ORDER IMPLEMENTING THE CORRECTIVE STATEMENTS REMEDY UNDER ORDER #1015 AND ORDER #34-REMAND Upon consideration of the Joint Motion for Consent Order Implementing the Corrective Statements Remedy under Order #1015 and Order #34-Remand (Dkt. No. 6021; filed 1/10/2014), and the entire record herei'n, it is hereby ORDERED that: The corrective statements remedy under Order #1015 (DN 5733, Aug. 17, 2006), published as United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc., 449 F. Supp. 2d 1, 938-41 (D.D.C. 2006), aff'd in part & vacated in part, 566 F.3d 1095 (D.C. Cir. 2009) (per curiam), cert. denied, 561 U.S._, 130 S. Ct. 3501 (2010), is hereby MODIFIED as set forth below: 1 Case 1:99-cv-02496-GK Document 6095 Filed 06/02/14 Page 2 of 27 I. Definitions A. "Above the Fold" means: 1. For websites other than mobile websites, the text that begins on the first screen of the home page for the web address, without scrolling, or 2. For mobile websites that do not use responsive design, the text that begins on the first screen in portrait orientation, without scrolling. B. "Benchmark timeslot" for a particular month means the timeslot that received the fewest average impressions (18-99+) among CBS, ABC, and NBC, Monday through Thursday, between 7:00p.m. -

To View the Sankofa African Heritage Book List

A B C D E F COPY- TITLE AUTHORS ED PUBLISHER(S) COVER ANNOTATION 1 RIGHT African Origins of the Majors Yosef Ben jochannan 1970- All Western religions had 2 Western Religions Yosef Ben Jochannan Publishing 360pp Paper their beginnings in Africa The Encyclopedia of the 1999- African and African American 3 AFRICANA Kwame-Gates, editors Basic Civitas Books 2045pp Cloth Experience 2002- 4 Africans Americans David Boyle Barrons 127pp Cloth Coming to America Today, we live in a changed Al on America, The Right Reverend Kingsenton Publishing 2002- America, changed by people 5 Al Sharpton Karen Hunter Group 280pp Cloth who risk their own lives. 2009- What Should Black People Do 6 America I Am Legends Foreword : Tavis Smiley Smiley books 180pp Paper Now? Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, 2008- and Forgotten Founders who 7 America's Hidden History Kenneth C. Davis Smithsonian Books 265pp Cloth shaped a Nation Ancient Egypt, The Light of the 1990- A work of reclamation and 8 World,Vol 1-B and vol.2--A Gerald Massey ECA Associates 750pp Paper restitution in twelve volumes The teaching and prophetic wisdom of the Seven 1999- Hermetic laws of Ancient 9 Ancient Future Wayne B. Chandler Black Classic Press 246pp Paper Egypt 2009- The U.S. Commission on Civil 10 And Justice For All Mary Frances Berry Knopf Publishers 425pp Cloth Rights 1995- Everyday liife ritual and court 11 Art and Craft in Africa Laure Meyer Terrial Publishers, Montreal 208pp Paper art B.B. King and Dick 2005- Collection of treasures of 12 B.B.King- Treasures Waterman Bulfinch Press 160pp cloth B.B. -

Some Articles Provided by a Member of the Public on Issues Relating To

PRESS RELEASE LC Paper No. CB(2)456/17-18(01) tobaccofreekids.org /press-releases/2017_11_20_corrective_statements Starting this Week, Tobacco Companies Must Run Court-Ordered Ads Telling the Truth about Their Lethal Products Statement of the American Cancer Society, American Heart Association, American Lung Association, Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights, National African American Tobacco Prevention Network and the Tobacco-Free Kids Action Fund (public health intervenors in the case) November 20, 2017 WASHINGTON, D.C. – Starting Nov. 26, the major U.S. tobacco companies must run court-ordered newspaper and television advertisements that tell the American public the truth about the deadly consequences of smoking and secondhand smoke, as well as the companies’ intentional design of cigarettes to make them more addictive. The ads are the culmination of a long-running lawsuit the U.S. Department of Justice filed against the tobacco companies in 1999. A federal court in 2006 ordered the tobacco companies to make these “corrective statements” after finding that they had violated civil racketeering laws (RICO) and engaged in a decades-long conspiracy to deceive the American public about the health effects of smoking and how they marketed to children. The ads will finally run after 11 years of appeals by the tobacco companies aimed at delaying and weakening them. View the full text of the corrective statements and details on when and where they will run. Make no mistake: The tobacco companies are not running these ads voluntarily or because of a legal settlement. They were ordered to do so by a federal court that found they engaged in massive wrongdoing that has resulted in “a staggering number of deaths per year, an immeasurable amount of human suffering and economic loss, and a profound burden on our national health care system,” as U.S. -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

African American Newsline Distribution Points

African American Newsline Distribution Points Deliver your targeted news efficiently and effectively through NewMediaWire’s African−American Newsline. Reach 700 leading trades and journalists dealing with political, finance, education, community, lifestyle and legal issues impacting African Americans as well as The Associated Press and Online databases and websites that feature or cover African−American news and issues. Please note, NewMediaWire includes free distribution to trade publications and newsletters. Because these are unique to each industry, they are not included in the list below. To get your complete NewMediaWire distribution, please contact your NewMediaWire account representative at 310.492.4001. A.C.C. News Weekly Newspaper African American AIDS Policy &Training Newsletter African American News &Issues Newspaper African American Observer Newspaper African American Times Weekly Newspaper AIM Community News Weekly Newspaper Albany−Southwest Georgian Newspaper Alexandria News Weekly Weekly Newspaper Amen Outreach Newsletter Newsletter Annapolis Times Newspaper Arizona Informant Weekly Newspaper Around Montgomery County Newspaper Atlanta Daily World Weekly Newspaper Atlanta Journal Constitution Newspaper Atlanta News Leader Newspaper Atlanta Voice Weekly Newspaper AUC Digest Newspaper Austin Villager Newspaper Austin Weekly News Newspaper Bakersfield News Observer Weekly Newspaper Baton Rouge Weekly Press Weekly Newspaper Bay State Banner Newspaper Belgrave News Newspaper Berkeley Tri−City Post Newspaper Berkley Tri−City Post -

Court-‐Ordered Corrective Statements Remedy

Court-Ordered Corrective Statements Remedy: Implementation Details United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc. In 2006, U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler found the major tobacco companies guilty of violating civil racketeering laws (RICO) and engaging in a decades-long conspiracy to deceive the American public about the health effects of smoking and their marketing to children. Among her remedies, Judge Kessler ordered the tobacco companies to publish corrective statements about the adverse health effects of smoking and secondhand smoke and other topics. The companies must disseminate the corrective statements through television and newspaper advertising, their websites and cigarette packaging. After 11 years of appeals by the tobacco companies to weaken and delay the corrective statements, a federal judge issued a final order directing them to begin running the corrective statement ads in newspapers on Sunday, November 26, 2017, with the television ads beginning the following day. Implementation details are still being finalized for the company websites and cigarette packs. Television: The Defendant tobacco companies will purchase television ads with text and voice-over containing one of the five corrective statements. • The ads will run five times per week for one year (52 weeks) for a total of 260 spots. • The ads can run Monday through Thursday between 7:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m. on one of the three major networks (CBS, ABC or NBC). Each month, up to one-third of the ads may be placed during programs on other networks or channels, provided that program has an overall audience at least as large as a program on one of the three major networks during the assigned time slots. -

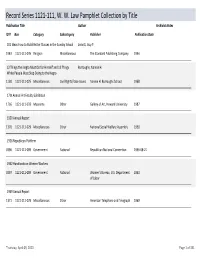

Rpt-Pamphlets by Title

Record Series 1121‐111, W. W. Law Pamphlet Collection by Title Publication Title Author Archivist Notes ID #Box Category Subcategory Publisher Publication Date 101 Ideas How to Build Better Classes in the Sunday School Leavitt, Guy P. 19431121‐111‐035 Religion Miscellaneous The Standard Publishing Company 1954 12 Things the Negro Must Do for Himself and 12 Things Burroughs, Nannie H. White People Must Stop Doing to the Negro 11301121‐111‐025 Miscellaneous Civil Rights/Race Issues Nannie H. Burroughs School 1968 17th Annual Art Faculty Exhibition 17161121‐111‐033 Museums Other Gallery of Art, Howard University 1987 1950 Annual Report 13701121‐111‐029 Miscellaneous Other National Social Welfare Assembly 1950 1956 Republican Platform 03961121‐111‐009 Government National Republican National Convention 1956‐08‐21 1962 Handbook on Women Workers 03971121‐111‐009 Government National Women's Bureau, U.S. Department 1963 of Labor 1969 Annual Report 13711121‐111‐029 Miscellaneous Other American Telephone and Telegraph 1969 Thursday, April 09, 2020 Page 1 of 341 Publication Title Author Archivist Notes ID #Box Category Subcategory Publisher Publication Date 1969 Journal Georgia Annual Conference of The United Pages 88 and 10 marked Methodist Church 19011121‐111‐034 Religion Methodist Publications The United Methodist Church, 1969‐05 Southeastern Jurisdiction 1970 Journal of the Georgia Conference 19021121‐111‐034 Religion Methodist Publications The United Methodist Church, 1970‐05 Southeastern Jurisdiction 1970 State of Georgia, Chatham County, and -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to t>e removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 3(X) North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA UMI 800-521-0600 UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE FOUNDATIONS OF AFROCENTRIC THOUGHT AND PRACTICE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS AS AN ALTERNATIVE EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY FOR .AERICAN AMERICAN INDIVIDUAL AND COMMUNITY EMPOWERMENT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION By Raushan Paul Ashanti-Alexander Norman, Oklahoma 1999 UMI Number 9952408 UMI UMI Microform9952408 Copyright 2000 by Bell & Howell Information and Leaming Company. -

Faculty Activites Related to Anti-Black Racism Work

Attachment A – Faculty Activities Related to Anti-Black Racism UCI Law Research and Creative Activities (as of July 2, 2020) Faculty Contributions – Primary Expertise in Anti-Black Racism Mehrsa Baradaran Books MEHRSA BARADARAN, THE COLOR OF MONEY: BLACK BANKS AND THE RACIAL WEALTH GAP (2019). MEHRSA BARADARAN, HOW THE OTHER HALF BANKS: EXCLUSION, EXPLOITATION, AND THE THREAT TO DEMOCRACY (2018). Journal Articles Baradaran, Mehrsa, Banking On Democracy (May 21, 2020). Washington University Law Review, 2020, forthcoming; UC Irvine School of Law Research Paper No. 2020-44. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3607461 Linda S. Greene et al., Talking about Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, 34 WIS. J. L. GENDER, & SOC’Y 109–178 (2019). Mehrsa Baradaran, Jim Crow Credit, 9 UC IRVINE L. REV. 887–952 (2018). Mehrsa Baradaran, How the Poor Got Cut out of Banking, 62 EMORY L.J. 483–548 (2012). Articles in Mainstream Outlets Mehrsa Baradaran, How the Right Used Free Market Capitalism against the Civil Rights 1 Attachment A – Faculty Activities Related to Anti-Black Racism Movement, JUST MONEY (2020), https://justmoney.org/m-baradaran-how-the-right- used-free-market-capitalism-against-the-civil-rights-movement/ (last visited Jun 12, 2020). Mehrsa Baradaran, The Roots of “Black Capitalism”: [Op-Ed], NEW YORK TIMES, April 1, 2019, at A.21. Mehrsa Baradaran, The Real Roots of ‘Black Capitalism,’ NEW YORK TIMES (ONLINE), March 31, 2019, https://search.proquest.com/usmajordailies/docview/2200390674/4D225707C7A4 5D3PQ/3?accountid=14509 (last visited Jun 25, 2020). Mehrsa Baradaran, The Post Office Banks on the Poor: Commentary, NEW YORK TIMES, February 8, 2014, at A.19. -

January 20, 2006

NEWSSTAND PRICE $6.50 JANUARY 20, 2006 Urban Loves Keyshia Cole The View From The Top The Interscope /A &M artist scores Most Added at Urban Throughout 2006, Urban this week as "Love" picks Editor Dana Hall will spotlight up 56 adds - over 85% prominent African -American of the panel. The track is broadcast owners in a off the 21- year -old monthly series. She kicks off Oakland, CA native's with an extensive and debut CD, The Way It Is. interesting interview with If you want to read more Perry Broadcasting President about her, check out the Russell Perry (pictured), who January- February issue of owns 10 stations in Oklahoma. King: Cole is featured as Discover the secrets of his the cover story. success. Page 37. F-v Po 17) 1 e r-- TRLAJ1\ HOSTED BY SUSIE CASTILLO MTV's TRL branded bilingual radio show features the best from the world of Reggaeton, Rhythmic, Latino music and entertainment. TRLatino esta en fuego with two hours of the hottest tracks, a Top 20 Weekly countdown, exclusive artist interviews, TRL clips, MTV News briefs, weekly song premieres, personalized artist lines, and more. Caution This show is so hot MTV strongly recommends that you DO NOT touci your radio dial and assumes no responsibility for scorched fingers or melted speakers. NOW HEARD IN: WSKQ FM New York KXOL FM Los Angeles WPOW FM Miami KTCY FM Dallas KYLD FM San Francisco WCMN FM Puerto Rico www.americanradiohistory.com Pot N T- T o - P O I N T DIRECT MARKETING SOLUTIONS Sk. -

In Re Black Farmers' Discrimination Litigation

Multiple Documents Part Description 1 7 pages 2 Memorandum in Support of Motion for Preliminary Approval 3 Exhibit 1 - Proposed Preliminary Approval Order 4 Exhibit 2 - Settlement Agreement 5 Exhibit 3 - Pigford Consent Decree 6 Exhibit 4 - Declaration of Richard Bithell 7 Exhibit 5 - Declaration of Katherine Kinsella and Associated Notice Materials 8 Exhibit 6 - Order of July 14, 2000 9 Exhibit 7 - Qualifications of Epiq Systems, Inc. 10 Exhibit 8 - Qualifications of The McCammon Group 11 Exhibit 9 - Qualifications of Michael Lewis 12 Exhibit 10 - Proposed Ombudsman Order of Appointment 13 Exhibit 11 - Proposed Ombudsman Order of Reference 14 Exhibit 12 - Declaration of Andrew H. Marks 15 Exhibit 13 - Qualifications of Proposed Class Counsel © 2012 Bloomberg Finance L.P. All rights reserved. For terms of service see bloomberglaw.com // PAGE 1 Document Link: http://www.bloomberglaw.com/ms/document/X1Q6L0JC3GO2?documentName=188.xml Case 1:08-mc-00511-PLF Document 161 Filed 03/30/11 Page 1 of 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) In re BLACK FARMERS DISCRIMINATION ) LITIGATION ) ) ) Misc. No. 08-mc-0511 (PLF) ) This document relates to: ) ) ALL CASES ) ) MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY APPROVAL OF SETTLEMENT, CERTIFICATION OF A RULE 23(b)(1)(B) SETTLEMENT CLASS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Plaintiffs James Copeland, Earl Moorer (on behalf of the estate of John Moorer), and Marshallene McNeil on behalf of themselves and the proposed Class they seek to represent, respectfully move this Court to enter the proposed Order Granting Preliminary Approval of Settlement Agreement, Certifying a Rule 23(b)(1)(B) Class, and for Other Purposes (“Preliminary Approval Order”) (Ex. -

Rpt-Pamphlets by Publisher

Record Series 1121‐111, W. W. Law Pamphlet Collection By Publisher Publisher Publication Title Author Archivist Notes ID #Box Category Subcategory Publication Date 1972 Democratic For the People as Presented to the 1972 Democratic Platform Committee National Convention 04821121‐111‐010 Government National 1972 93rd Congress The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America 04451121‐111‐009 Government National 1975 93rd U.S. Congress Public Law 93‐383 05591121‐111‐011 Government National 1974‐08‐22 95th Congress of Black Americans in Congress, 1870‐1977 the United States 02871121‐111‐006 Government Civil Rights/Race 1977 A. M. E. Sunday Richard Allen and Present Day Social Problems: A Socio‐ Gregg, Howard D. Copy 3 has note inscribed, "Best School Union Psychological Study of the Background, Principles of the wishes, Howard D. Gregg" A. M. E. in the Light of Contemporary Thought and Actions 18931121‐111‐034 Religion Racial Issues 1950s‐1960s [circa] A. Philip Randolph A. Philip Randolph Educational Fund 12621121‐111‐027 Miscellaneous Black History/Culture 1960s‐1970s [circa] Thursday, April 09, 2020 Page 1 of 400 Publisher Publication Title Author Archivist Notes ID #Box Category Subcategory Publication Date A. Philip Randolph The Neglected Black Majority: Essays on the Attitudes Brimmer, Andrew F.; Charles V. Hamilton; John Educational Fund and Concerns of Some Forgotten Americans A. M 11681121‐111‐025 Miscellaneous Civil Rights/Race Issues 1971‐05 A. Philip Randolph A "Freedom Budget" for All Americans: A Summary Institute 14901121‐111‐030 Miscellaneous Other 1967‐01 A. Philip Randolph A "Freedom Budget" for All Americans: Budgeting Our Institute Resources, 1966‐1975, to Achieve "Freedom from Want" 14911121‐111‐030 Miscellaneous Other 1966‐10 A.