Uvic Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

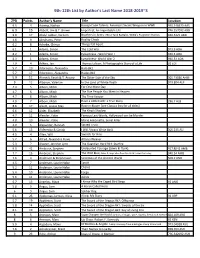

9Th-12Th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S

9th-12th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 9.5 4 Aaseng, Nathan Navajo Code Talkers: America's Secret Weapon in WWII 940.548673 AAS 6.9 15 Abbott, Jim & T. Brown Imperfect, An Improbable Life 796.357092 ABB 9.9 17 Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Brothers in Arms: 761st Tank Battalio, WW2's Forgotten Heroes 940.5421 ABD 4.6 9 Abrahams, Peter Reality Check 6.2 8 Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart 6.1 1 Adams, Simon The Cold War 973.9 ADA 8.2 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness - World War I 940.3 ADA 8.3 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness- World War 2 940.53 ADA 7.9 4 Adkins, Jan Thomas Edison: A Photographic Story of a Life 92 EDI 5.7 19 Adornetto, Alexandra Halo Bk1 5.7 17 Adornetto, Alexandra Hades Bk2 5.9 11 Ahmedi, Farah & T. Ansary The Other Side of the Sky 305.23086 AHM 9 12 Albanov, Valerian In the Land of White Death 919.804 ALB 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For One More Day 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper 4.9 7 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: a True Story 296.7 ALB 8.6 17 Alcott, Louisa May Rose in Bloom [see Classics lists for all titles] 6.6 12 Alder, Elizabeth The King's Shadow 4.7 11 Alender, Katie Famous Last Words, Hollywood can be Murder 4.8 10 Alender, Katie Marie Antoinette, Serial Killer 4.9 5 Alexander, Hannah Sacred Trust 5.6 13 Aliferenka & Ganda I Will Always Write Back 305.235 ALI 4.5 4 Allen, Will Swords for Hire 5.2 6 Allred, Alexandra Powe Atticus Weaver 5.3 7 Alvarez, Jennifer Lynn The Guardian Herd Bk1: Starfire 9.0 42 Ambrose, Stephen Undaunted Courage -

" Dragon Tales." 1992 Montana Summer Reading Program. Librarian's Manual

-DOCUMENT'RESUME------ ED 356 770 IR 054 415 AUTHOR Siegner, Cathy, Comp. TITLE "Dragon Tales." 1992 Montana Summer Reading Program. Librarian's Manual. INSTITUTION Montana State Library, Helena. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 120p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reference Arterials Bibliographies (131) Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Braille; *Childrens Libraries; *Childrens Literature; Disabilities; Elementary Education; Games; Group Activities; Handicrafts; *Library Services; Program Descriptions; Public Libraries; *Reading Programs; State Programs; Story Telling; *Summer Programs; Talking Books IDENTIFIERS *Montana ABSTRACT This guide contains a sample press release, artwork, bibliographies, and program ideas for use in 1992 public library summer reading programs in Montana. Art work incorporating the dragon theme includes bookmarks, certificates, reading logs, and games. The bibliography lists books in the following categories: picture books and easy fiction (49 titles); non-fiction, upper grades (18 titles); fiction, upper grades (45 titles); and short stories for easy telling (13 titles). A second bibliography prepared by the Montana State Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped provides annotations for 133 braille and recorded books. Suggestions for developing programs around the dragon and related themes, such as the medieval age, knights, and other mythic creatures, are provided. A description of craft projects, puzzles, and other activities concludes -

Of Titles (PDF)

Alphabetical index of titles in the John Larpent Plays The Huntington Library, San Marino, California This alphabetical list covers LA 1-2399; the unidentified items, LA 2400-2502, are arranged alphabetically in the finding aid itself. Title Play number Abou Hassan 1637 Aboard and at Home. See King's Bench, The 1143 Absent Apothecary, The 1758 Absent Man, The (Bickerstaffe's) 280 Absent Man, The (Hull's) 239 Abudah 2087 Accomplish'd Maid, The 256 Account of the Wonders of Derbyshire, An. See Wonders of Derbyshire, The 465 Accusation 1905 Aci e Galatea 1059 Acting Mad 2184 Actor of All Work, The 1983 Actress of All Work, The 2002, 2070 Address. Anxious to pay my heartfelt homage here, 1439 Address. by Mr. Quick Riding on an Elephant 652 Address. Deserted Daughters, are but rarely found, 1290 Address. Farewell [for Mrs. H. Johnston] 1454 Address. Farewell, Spoken by Mrs. Bannister 957 Address. for Opening the New Theatre, Drury Lane 2309 Address. for the Theatre Royal Drury Lane 1358 Address. Impatient for renoun-all hope and fear, 1428 Address. Introductory 911 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of Drury Lane Theatre 1827 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of the Hay Market Theatre 2234 Address. Occasional. In early days, by fond ambition led, 1296 Address. Occasional. In this bright Court is merit fairly tried, 740 Address. Occasional, Intended to Be Spoken on Thursday, March 16th 1572 Address. Occasional. On Opening the Hay Marker Theatre 873 Address. Occasional. On Opening the New Theatre Royal 1590 Address. Occasional. So oft has Pegasus been doom'd to trial, 806 Address. -

Volume One: Arthur and the History of Jack and the Giants

The Arthuriad – Volume One CONTENTS ARTICLE 1 Jack & Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant-Killer DOCUMENTS 5 The History of Jack and the Giants (1787) 19 The 1711 Text of The History of Jack and the Giants 27 Jack the Giant Killer: a c. 1820 Penny Book 32 Some Arthurian Giant-Killings Jack & Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant-Killer Caitlin R. Green The tale of Jack the Giant-Killer is one that has held considerable fascination for English readers. The combination of gruesome violence, fantastic heroism and low cunning that the dispatch of each giant involves gained the tale numerous fans in the eighteenth century, including Dr Johnson and Henry Fielding.1 It did, indeed, inspire both a farce2 and a ‘musical entertainment’3 in the middle of that century. However, despite this popularity the actual genesis of Jack and his tale remains somewhat obscure. The present collection of source materials is provided as an accompaniment to my own study of the origins of The History of Jack and the Giants and its place within the wider Arthurian legend, published as ‘Tom Thumb and Jack the Giant-Killer: Two Arthurian Fairy Tales?’, Folklore, 118.2 (2007), pp. 123-40. The curious thing about Jack is that – in contrast to that other fairy-tale contemporary of King Arthur’s, Tom Thumb – there is no trace of him to be found before the early eighteenth century. The first reference to him comes in 1708 and the earliest known (now lost) chapbook to have told of his deeds was dated 1711.4 He does not appear in Thackeray’s catalogue of chapbooks -

Early Arthurian Tradition and the Origins of the Legend

Arthuriana Arthuriana Early Arthurian Tradition and the Origins of the Legend Thomas Green THE LINDES PRESS As with everything, so with this: For Frances and Evie. First published 2009 The Lindes Press Louth, Lincolnshire www.arthuriana.co.uk © Thomas Green, 2009 The right of Thomas Green to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing of the Author. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 4452 2110 6 Contents Preface vii 1 The Historicity and Historicisation of Arthur 1 2 A Bibliographic Guide to the Welsh Arthurian Literature 47 3 A Gazetteer of Arthurian Onomastic and Topographic Folklore 89 4 Lincolnshire and the Arthurian Legend 117 5 Arthur and Jack the Giant-Killer 141 a. Jack & Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant-Killer 143 b. The History of Jack and the Giants (1787) 148 c. The 1711 Text of The History of Jack and the Giants 166 d. Jack the Giant Killer: a c. 1820 Penny Book 177 e. Some Arthurian Giant-Killings 183 6 Miscellaneous Arthuriana 191 a. An Arthurian FAQ: Some Frequently Asked Questions 193 b. The Monstrous Regiment of Arthurs: A Critical Guide 199 c. An Arthurian Reference in Marwnad Gwên? The Manuscript 217 Evidence Examined d. -

Some Big Names in Myth and Folklore John Giants Can Be Found in Folklore All Around the World

good john © good john © good john © good john © good john © john © good good john © john © good good good john good john © john good © © john good good © john good good good © john good john good © So what makes a real giant? Everyone knows that to be a giant you have to be tall. But can john human beings ever be called giants? The tallest person that ever lived was the American Robert good © Wadlow, who was a staggering 8 foot 11 and john (2.72m) tall when he died, aged only 22. Some believe that he Some big names in myth and folklore would have topped 9 foot if he had lived longer. In September Giants can be found in folklore all around the world. Here are good 2009 the Guinness Book of World Records officially named Sultan some of the most famous: Kösen, from Turkey, as the “World’s Tallest Man”, he measured © in at a towering 8 foot 1 inch tall. When asked of his hopes for johnFinn MacCumhaill (MacCool) the future, Kösen replied that he would love to be able to drive A legendary Irish giant who is said to have built the a car (they are all too small for him!) and find a girlfriend. extraordinary Giant’s Causeway, a series of ‘steps’ of Such people are huge, but are not really giants as we think of © hexagonal basalt columns to be seen off the northern coast of them in fairy-tale terms. A real giant would have to be much Northern Ireland. According to legend, Finn MacCumhaill built john taller than that, and much bigger in every way: bigger hands, the causeway to help him cross the sea to the Scottish island bigger heads and bigger eyes, not to mention mouths big of Staffa (which has similar rock formations). -

Transactions Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History Antiquarian Society

Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society LXXXIII 2009 Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society FOUNDED 20th NOVEMBER, 1862 THIRD SERIES VOLUME LXXXIII Editors: JAMES WILLIAMS, R. McEWEN and FRANCIS TOOLIS ISSN 0141-1292 2009 DUMFRIES Published by the Council of the Society Office-Bearers 2008-2009 and Fellows of the Society President Morag Williams, MA Vice Presidents Mr J McKinnell, Dr A Terry, Mr J L Williams and Mrs J Brann Fellows of the Society Mr J Banks, BSc; Mr A D Anderson, BSc; Mr J Chinnock; Mr J H D Gair, MA, Dr J B Wilson, MD; Mr K H Dobie; Mrs E Toolis, BA and Dr D F Devereux, PhD. Mr J Williams, Mr L J Masters and Mr R H McEwen — appointed under Rule 10 Hon. Secretary John L Williams, Merkland, Kirkmahoe, Dumfries DG1 1SY Hon. Membership Secretary Miss H Barrington, 30 Noblehill Avenue, Dumfries DG1 3HR Hon. Treasurer Mr L Murray, 24 Corberry Park, Dumfries DG2 7NG Hon. Librarian Mr R Coleman, 2 Loreburn Park, Dumfries DG1 1LS Assisted by Mr J Williams, 43 New Abbey Road, Dumfries DG2 7LZ Joint Hon. Editors Mr J Williams and Mr R H McEwen, 5 Arthur’s Place, Lockerbie DG11 2EB Assisted by Dr F Toolis, 25 Dalbeattie Road, Dumfries DG2 7PF Hon. Syllabus Convener Mrs E Toolis, 25 Dalbeattie Road, Dumfries DG2 7PF Hon. Curators Mrs J Turner and Ms S Ratchford Hon. Outings Organisers Mr J Copland and Mr Alastair Gair Ordinary Members Mr R Copland, Dr J Foster, Mrs P G Williams, Mr D Rose, Mrs C Inglehart, Mr A Pallister, Mr R McCubbin, Dr F Toolis, Mr I Wismach and Mrs J Turner CONTENTS Ostracods from the Wet Moat at Caerlaverock Castle by Mervin Kontrovitz and Huw I Griffiths ....................................................... -

Jack Giant Killer

JACK THE GIANT KILLER, A H E R O Celebrated by ancient Historians. BANBU RY: PRINTED BY J. G. RUSHER. THE HISTORY OF JACK THE GIANT KILLER. Kind Reader, Jack makes you a bow, The hero of giants the dread ; Whom king and the princes applaud For valour, whence tyranny fled. In Cornwall, on Saint Michael’s Mount A giant full eighteen feet high, Nine feet round, in cavern did dwell, For food cleared the fields and the sty And, glutton, would feast on poor souls, W hom chance might have led in his way Or gentleman, lady, or child, Or what on his hands he could lay. He went over to the main land, in search of food, when he would throw oxen or cows on his back, and several sheep and pigs, and with them wade to his abode in the cavern. 3 T ill Jack’s famed career made him quake, Blew his horn, took mattock and spade; Dug twenty feet deep near his den, And covered the pit he had made. The giant declared he’d devour For breakfast who dared to come near; And leizurely did Blunderbore Walk heavily into the snare. 4 Then Jack with his pickaxe commenced, The giant most loudly did roar; H e thus made an end of the first— The terrible Giant Blunderbore. H is brother, who heard of Jack’s feat, Did vow he’d repent of his blows, From Castle Enchantment, in wood, Near which Jack did shortly repose. This giant, discovering our hero, weary and fast asleep in the wood, carried him to his castle, and locked him up in a large room, the floor of which was covered with the bones of men and women. -

Jack the Giant Killer

JACK, • .. Jach" resczt ll1JI ,/r11/,· ,l-Jcrst.11117/,,~// 11;,,: 71tt' Mich/ t/1an1 lr:Ft~tf! w or/?ak /:tal;~/Y /II tltf? /') 11 '/1 /I /j 1:5"' <;•/rJ/./1 // r.i . lr1rl·.:.· Z,-,111'. ~·. ~~~~~~~--~ THE SURPRISING HISTORY -• OF THE GIANT-IiILLER ,- EKBBLLI-SHBD WITH A -'COLOUltED FRON<rISPIEC£. tONDON·: PRINTED AND 50tD B~ .l)JsAN & MUNDAY, THREADNEEDLE+STREET. Prioo Si«-pence. Jack the Giant Killer . ... In the reign of the famous King Ar~.hur, there lived, near the Land's End of Eng land, in the County of Cornwall, a worthy farmer, who had an only son, named Jack. Jack was a boy of a bold temper; he took pleasure in hearing, or reading, stories of wizards, conjurors, giants, and fairies; and used to listen eagerly, while his father talked of the great deeds of the brave knights of King Arthur's round table. When Jack was sent to take care of the sheep and oxen in the fields, he used to sieges, amuse himself 1with planning battles, and the means to conquer or surprise a foe. He was above the common sports of children; but hardly any one could equal him at wrestling; or if he met with a :B 3 JACK, THE match for' himself in strength, his skill and address always made him. victor In those days, there lived on St. Mi chael's mount, off Cornwall, which rises out of the sea at some distance from the 1nain land, a huge Giant. He was eighteen feet high, and three yards round; and his :fierce and savage looks were the terror of all his neighbours. -

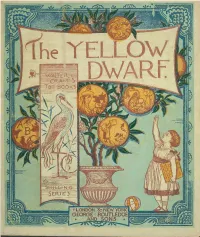

The Yellow Dwarf

PS/ - %f# MS^&S ssr ~ ^ ga, - ^ m • - v jlkp * v * 5^8$ . '^Sp^ : LONDON ^ NEW YORIO GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS * x Q) o y; £ tq s tj s a ^ £ THE YELLOW DfARF. <So =*- Q) -*=C^£®-%©3 •O a M <1 i^ so cq C E upon a time there was a Que who had an only daughter, co and she was so fond of her t she never corrected 5 0 O o C ^ • FO her faults; therefore the Jo Princess became siroud, and so vain £q $ of her beauty that she despised everybody. T Queen gave her the name of T outebelle ; and sent her portrait toveral friendly kings. As soon as they saw it, they all fell in love w her. The Queen, however, saw no means of inducing her to dec in favour of one of them, so, not knowing what to do, she went) consult a powerful Fairy, called the Fairy of the Desert : but it v. not easy to see her, for she was guarded by lions. The Queen mid have had little chance if she had not known how to prepa a cake that would appease them. She made one herself, put it b a little basket, and set out on her journey. Being tired with wang, she lay down at the foot of a tree and fell asleep and on asking, she found her ; basket empty, and the cake gone, while the lio were roaring dread- fully. “ Alas, what will ” to become of me ! shexclaimed, clinging the tree. Just then she heard, “Hist! A-hn!” and raising her eyes, she saw up in the tree a little man not nre than two feet high. -

The Arthuriad – Volume One CONTENTS

The Arthuriad – Volume One CONTENTS ARTICLE 1 Jack & Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant-Killer DOCUMENTS 5 The History of Jack and the Giants (1787) 19 The 1711 Text of The History of Jack and the Giants 27 Jack the Giant Killer: a c. 1820 Penny Book 32 Some Arthurian Giant-Killings Jack & Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant-Killer Thomas Green The tale of Jack the Giant-Killer is one that has held considerable fascination for English readers. The combination of gruesome violence, fantastic heroism and low cunning that the dispatch of each giant involves gained the tale numerous fans in the eighteenth century, including Dr Johnson and Henry Fielding.1 It did, indeed, inspire both a farce2 and a ‘musical entertainment’3 in the middle of that century. However, despite this popularity the actual genesis of Jack and his tale remains somewhat obscure. The present collection of source materials is provided as an accompaniment to my own study of the origins of The History of Jack and the Giants and its place within the wider Arthurian legend, published as ‘Tom Thumb and Jack the Giant-Killer: Two Arthurian Fairy Tales?’, Folklore, 118.2 (2007), pp. 123-40. The curious thing about Jack is that – in contrast to that other fairy-tale contemporary of King Arthur’s, Tom Thumb – there is no trace of him to be found before the early eighteenth century. The first reference to him comes in 1708 and the earliest known (now lost) chapbook to have told of his deeds was dated 1711.4 He does not appear in Thackeray’s catalogue of chapbooks in -

Jack Dempsey in Tampa: Sports and Boosterism in the 1920S

Tampa Bay History Volume 14 Issue 2 Article 3 12-1-1992 Jack Dempsey in Tampa: Sports and Boosterism in the 1920s Jack Moore University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tampabayhistory Recommended Citation Moore, Jack (1992) "Jack Dempsey in Tampa: Sports and Boosterism in the 1920s," Tampa Bay History: Vol. 14 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tampabayhistory/vol14/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tampa Bay History by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moore: Jack Dempsey in Tampa: Sports and Boosterism in the 1920s JACK DEMPSEY IN TAMPA: SPORTS AND BOOSTERISM IN THE 1920s by Jack Moore On Wednesday afternoon February 4, 1926, heavyweight champion of the world William Harrison “Jack” Dempsey fought seven rounds of exhibition matches with four opponents in an outdoor ring specially constructed on the property of real estate developer B.L. Hamner in what is now the Forest Hills section of Tampa. None of the estimated crowd of 10,000 paid a cent to see the famous conqueror of Jess Willard, Georges Carpentier, Luis Angel Firpo (“The Wild Bull of the Pampas”), and Tommy Gibbons demonstrate some of the skills and spectacular personal appeal that had made him one of the era’s greatest sports heroes. With the passage of time Dempsey would become an authentic legend, a sports immortal. Three other legendary sports’ heroes, Harold “Red” Grange, Jim Thorpe, and Babe Ruth also visited Tampa around the time of Dempsey’s appearance.