9781426731143.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

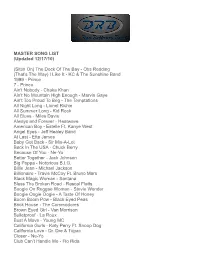

DRB Master Song List

MASTER SONG LIST (Updated 12/17/10) (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding (That’s The Way) I Like It - KC & The Sunshine Band 1999 - Prince 7 - Prince Ain't Nobody - Chaka Khan Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations All Night Long - Lionel Richie All Summer Long - Kid Rock All Blues - Miles Davis Always and Forever - Heatwave American Boy - Estelle Ft. Kanye West Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band At Last - Etta James Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-A-Lot Back In The USA - Chuck Berry Because Of You - Ne-Yo Better Together - Jack Johnson Big Poppa - Notorious B.I.G. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Billionaire - Travie McCoy Ft. Bruno Mars Black Magic Woman - Santana Bless The Broken Road - Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman - Stevie Wonder Boogie Oogie Oogie - A Taste Of Honey Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Brick House - The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Bulletproof - La Roux Bust A Move - Young MC California Gurls - Katy Perry Ft. Snoop Dog California Love - Dr. Dre & Tupac Closer - Ne-Yo Club Can’t Handle Me - Flo Rida Cowboy - Kid Rock Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Crazy In Love - Beyonce ft. Jay Z Dancing In The Streets - Martha and The Vendellas Disco Inferno - The Trammps DJ Got Us Falling In Love - Usher Don’t Stop Believing - Journey Don’t Stop The Music - Rihanna Drift Away - Uncle Kracker Dynamite - Taio Cruz Evacuate The Dance Floor - Cascada Everything - Michael Bublé Faithfully - Journey Feelin Alright - Joe Cocker Fight For Your Right - Beastie Boys Fly Away - Lenny Kravitz Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Free Fallin’ - Tom Petty Funkytown - Lipps, Inc. -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

Black Youth in Urban America Marcyliena Morgan Harvard

“Assert Myself To Eliminate The Hurt”: Black Youth In Urban America Marcyliena Morgan Harvard University (Draft – Please Do Not Quote) Marcyliena Morgan [email protected] Graduate School of Education Human Development & Psychology 404 Larsen Hall 14 Appian Way Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Office:617-496-1809 (617)-264-9307 (FAX) 1 Marcyliena Morgan Harvard University “Assert Myself To Eliminate The Hurt”: Black Youth In Urban America Insert the power cord so my energy will work Pure energy spurts, sporadic, automatic mathematic, melodramatic -- acrobatic Diplomatic, charismatic Even my static, Asiatic Microphone fanatic 'Alone Blown in, in the whirlwind Eye of the storm, make the energy transform and convert, introvert turn extrovert Assert myself to eliminate the hurt If one takes more than a cursory glance at rap music, it is clear that the lyrics from some of hip hop’s most talented writers and performers are much more than the visceral cries of betrayed and discarded youth. The words and rhymes of hip hop identify what has arguably become the one cultural institution that urban youth rely on for honesty (keeping it real) and leadership. In 1996, there were 19 million young people aged 10-14 years old and 18.4 million aged 15-19 years old living in the US (1996 U.S. Census Bureau). According to a national Gallup poll of adolescents aged 13-17 (Bezilla 1993) since 1992, rap music has become the preferred music of youth (26%), followed closely by rock (25%). Though hip hop artists often rap about the range of adolescent confusion, desire and angst, at hip hop’s core is the commitment and vision of youth who are agitated, motivated and willing to confront complex and powerful institutions and practices to improve their 2 world. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

(2001) 96- 126 Gangsta Misogyny: a Content Analysis of the Portrayals of Violence Against Women in Rap Music, 1987-1993*

Copyright © 2001 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN 1070-8286 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 8(2) (2001) 96- 126 GANGSTA MISOGYNY: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE PORTRAYALS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN RAP MUSIC, 1987-1993* by Edward G. Armstrong Murray State University ABSTRACT Gangsta rap music is often identified with violent and misogynist lyric portrayals. This article presents the results of a content analysis of gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics. The gangsta rap music domain is specified and the work of thirteen artists as presented in 490 songs is examined. A main finding is that 22% of gangsta rap music songs contain violent and misogynist lyrics. A deconstructive interpretation suggests that gangsta rap music is necessarily understood within a context of patriarchal hegemony. INTRODUCTION Theresa Martinez (1997) argues that rap music is a form of oppositional culture that offers a message of resistance, empowerment, and social critique. But this cogent and lyrical exposition intentionally avoids analysis of explicitly misogynist and sexist lyrics. The present study begins where Martinez leaves off: a content analysis of gangsta rap's lyrics and a classification of its violent and misogynist messages. First, the gangsta rap music domain is specified. Next, the prevalence and seriousness of overt episodes of violent and misogynist lyrics are documented. This involves the identification of attributes and the construction of meaning through the use of crime categories. Finally, a deconstructive interpretation is offered in which gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics are explicated in terms of the symbolic encoding of gender relationships. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

GET 54095 SLICK RICK Children's Story AC

SLICK RICK • THE GREAT ADVENTURES OF... CHILDREN’S BOOK DELUXE THICK-PAGED CHILDREN’S BOOK BASED ON THE TITULAR HIP-HOP TRACK BY SLICK RICK! COMES BUNDLED WITH A COM- PACT DISC COPY OF HIS FAMED ALBUM “THE GREAT ADVENTURES OF” Treat Her Like A Prostitute • The Ruler's Back Children's Story • The Moment I Feared Let's Get Crazy • Indian Girl (An Adult Story) Teenage Love • Mona Lisa KIT (What's The Scoop) • Hey Young World Teacher, Teacher • Lick The Balls Storytelling has been a part of the hip-hop lexicon since the artform’s earliest days. And in all those decades, there has never been a tale- weaver like Slick Rick. Even masters who came along in Rick’s wake – ranging from Will Smith to Ghostface Killah and Eminem – know that even though they blazed their own paths, they never did it better than the Slick one When it comes to Rick and his tales, 1988’s “Children’s Story” is perhaps his best, recited to this day by fans and MCs in training as a rite of passage. Just hearing the opening lines begins a sing-along that can quickly fill a room: “Once upon a time / Not long ago / When people wore pajamas / And lived life slow….” Get On Down, known for its unique approach to packaging hip-hop classics, has come up with another winner here, presenting the lyrics to this immortal rap tale in never-before-seen form. Rick’s lines from the song are re-created in visual form in a 16 page book with a puffy cover – presented like a legit children’s book, thick pages and all. -

Man Depends on Former Wife for Everyday Needs

6A RECORDS/A DVICE TEXARKANA GAZETTE ✯ MONDAY, JULY 19, 2021 5-DAY LOCAL WEATHER FORECAST DEATHS Man depends on former TODAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY EUGENE CROCKETT JR. Eugene “Ollie” Crockett Jr., 69, of Ogden, AR, died Wednesday, July 14, 2021, in wife for everyday needs Ogden, AR. High-Upper 80s High-Upper 80s Mr. Dear Abby: I have been with my boy- but not yet. Low-Near 70 Low-Lower 70s Crockett was friend, “John,” for a year and a half. He had When people see me do things that are born May been divorced for two years after a 20-year considered hard work, they presume I need 19, 1952, in marriage when we got together. He told help. For instance, today I bought 30 cement THURSDAY FRIDAY Dierks, AR. He was a Car me he and his ex, “Jessica,” blocks to start building a wall. Several men Detailer. He Dear Abby were still good friends. I asked if I needed help. I refused politely as was preced- thought it was OK since I always do, saying they were thoughtful to Jeanne Phillips High-Upper 80s ed in death they were co-parenting offer but I didn’t need help. They replied, by his par- Low-Lower 70s High-Lower 90s High-Lower 90s their kid. I have children of “No problem.” Low-Lower 70s Low-Mid-70s ents, Bernice my own, and I understand. A short time later it started raining. A and Eugene Crockett Sr.; one I gave up everything and woman walked by carrying an umbrella sister, Bertha Lee Crockett; moved two hours away to and offered to help, and I responded just thunderstorms. -

Hip Hop-Decoded MUS 307/AFR 317

************************************************************* Music of African Americans: Hip Hop-Decoded MUS 307/AFR 317 Fall 2016 MRH 2.608 MWF 12-1pm Instructor: Dr. Charles Carson MBE 3.604 [email protected] Twitter: @UT_Doc_C 512.232.9448 Office hours: M 1-2pm, or by appointment Teaching Assistant: Rose Bridges Sections: Tuesday, 5-6pm (21360/30095) Tuesday, 6-7pm (21370/30105) Tuesday, 7-8pm (21380/30115)* Thursday, 5-6pm (21365/30100) Thursday, 6-7pm (21375/30110) I. Course Description: Generally speaking, this course is an introduction to the musical, social, cultural, and political elements of Hip Hop culture in the US, as interpreted through the development of its musical style. II. Course Aims and Objectives: Aims Beyond increasing familiarity with African American music and culture, a major goal of this course is to provide you with the tools to coexist--and indeed thrive--in a global context. Specific Learning Objectives: By the end of this course, students will: ● Be able to recognize and describe general elements of African American cultural practices, including instruments/media, performance practice, and aesthetics. ● Discuss the ways in which these elements have influenced (and continue to influence) contemporary American and global cultures, especially with respect to hip hop and related genres. ● Discuss the ways in which these elements have influenced (and continue to influence) contemporary American and global cultures, especially with respect to hip hop and related genres. ● Critically assess expressions and representations of African American culture in music and media. ● Be able to apply these critical thinking skills in the context of other cultures, both historical and contemporary. III.