Katerina Arvaniti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

End of Term Press Release

END OF TERM PRESS RELEASE The Epidaurus Lyceum - International Summer School of Ancient Drama successfully completed its inaugural year on 19 July. The programme was realised under the auspices and support of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, in collaboration with the Department of Theatre Studies, School of Fine Arts, University of the Peloponnese and the support of the Municipality of Epidaurus. A brand-new educational institution operating under the Athens & Epidaurus Festival, the Lyceum welcomed 120 students of drama schools and theatre studies university departments, as well as young actors from around the world for its first annual theme “The Arrival of the Outsider.” The Epidaurus Lyceum students attended a main five-hour practical workshop daily. In 2017, the teaching staff of the Lyceum for practical workshops consisted of the following: Phillip Zarrilli, a celebrated director, performer, and teacher of a technique for actors combining yoga and Asian martial arts; Simon Abkarian and Catherine Schaub Abkarian, core members of Ariane Mnouchkine’s legendary Théâtre du Soleil; Rosalba Torres Guerrero, one of the core members of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rosas dance group, along with dancer and choreographer Koen Augustijnen; Enrico Bonavera, actor and drama teacher, who has worked closely with Milan’s Piccolo Teatro; RootlessRoot, an ever-active dance company who has created the “Fighting Monkey” programme; Greek directors Martha Frintzila, Simos Kakalas, Sotiris Karamesinis, Kostantinos Ntellas, actress Rinio Kyriazi, and others. The 2017 programme of studies consisted of theory workshops, lectures, and masterclasses, in accordance to this year’s overarching theme. The majority of these events were open to the public, in an effort to strengthen the Lyceum’s ties to the local community. -

Laughter from Hades: Aristophanic Voice Today*

51 Ifigenija Radulović University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ismene Helen Radoulovits Petkovits National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Laughter from Hades: Aristophanic Voice Today The current Greek political situation again brings to light, and on stage, many ancient dramas. Contemporary Greek theatre professionals, not turning a blind eye to reality, have come up with ‘the revival’ of old texts, staging them in new circumstances. Aristophaniad is an original play with a subversive content inspired by Aristophanes and a contemporary street graffito reflecting contemporary Athenian life. It is a mixture of various comic and other dramatic elements, such as ancient comedy, grotesque, pantomime, musical, ballet, opera, standup, even circus. Additionally, staging methods developed by the Greek director, Karolos Koun (1908‐1987) are also evident in the production. Idea Theatre Company, exploiting excerpts from Aristophanes’ plays and starring the comediographer himself, manages to depict a fictional and real world in one. The performance starts with the rehearsal of Aristophanes’ new play, Poverty, which is in danger of being left unfinished since Hades plans to take Aristophanes to the Underworld. The play ends with Plutus. In the meantime, the performance entertains its audience, leading them to experience Aristotelian catharsis through laughter. This collective ‘purification’ of the soul is supposed to be mediated by laughter and provoked by references to serious life issues, given in comic mode and through a vast range of human emotions. The article deals with those comic features and supports the thesis that in spite of the fact that times change, people never cease to fight for a better society. -

Ancient Greek Myth and Drama in Greek Cinema (1930–2012): an Overall Approach

Konstantinos KyriaKos ANCIENT GREEK MYTH AND DRAMA IN GREEK CINEMA (1930–2012): AN OVERALL APPROACH Ι. Introduction he purpose of the present article is to outline the relationship between TGreek cinema and themes from Ancient Greek mythology, in a period stretching from 1930 to 2012. This discourse is initiated by examining mov- ies dated before WW II (Prometheus Bound, 1930, Dimitris Meravidis)1 till recent important ones such as Strella. A Woman’s Way (2009, Panos Ch. Koutras).2 Moreover, movies involving ancient drama adaptations are co-ex- amined with the ones referring to ancient mythology in general. This is due to a particularity of the perception of ancient drama by script writers and di- rectors of Greek cinema: in ancient tragedy and comedy film adaptations,3 ancient drama was typically employed as a source for myth. * I wish to express my gratitude to S. Tsitsiridis, A. Marinis and G. Sakallieros for their succinct remarks upon this article. 1. The ideologically interesting endeavours — expressed through filming the Delphic Cel- ebrations Prometheus Bound by Eva Palmer-Sikelianos and Angelos Sikelianos (1930, Dimitris Meravidis) and the Longus romance in Daphnis and Chloë (1931, Orestis Laskos) — belong to the origins of Greek cinema. What the viewers behold, in the first fiction film of the Greek Cinema (The Adventures of Villar, 1924, Joseph Hepp), is a wedding reception at the hill of Acropolis. Then, during the interwar period, film pro- duction comprises of documentaries depicting the “Celebrations of the Third Greek Civilisation”, romances from late antiquity (where the beauty of the lovers refers to An- cient Greek statues), and, finally, the first filmings of a theatrical performance, Del- phic Celebrations. -

The Greek Sale

athens nicosia The Greek Sale thursday 8 november 2018 The Greek Sale nicosia thursday 8 november, 2018 athens nicosia AUCTION Thursday 8 November 2018, at 7.30 pm HILTON CYPRUS, 98 Arch. Makarios III Avenue managing partner Marinos Vrachimis partner Dimitris Karakassis london representative Makis Peppas viewing - ATHENS athens representative Marinos Vrachimis KING GEORGE HOTEL, Syntagma Square for bids and enquiries mob. +357 99582770 mob. +30 6944382236 monday 22 to wednesday 24 october 2018, 10 am to 9 pm email: [email protected] to register and leave an on-line bid www.fineartblue.com viewing - NICOSIA catalogue design Miranda Violari HILTON CYPRUS, 98 Arch. Makarios III Avenue photography Vahanidis Studio, Athens tuesday 6 to wednesday 7 november 2018, 10 am to 9 pm Christos Panayides, Nicosia thursday 8 november 2018, 10 am to 6 pm exhibition instalation / art transportation Move Art insurance Lloyds, Karavias Art Insurance printing Cassoulides MasterPrinters ISBN 978-9963-2497-2-5 01 Yiannis TSAROUCHIS Greek, 1910-1989 The young butcher signed and dated ‘68 lower right gouache on paper 16.5 x 8.5 cm PROVENANCE private collection, Athens 1 800 / 3 000 € Yiannis Tsarouchis was born in 1910 in Piraeus, Athens. In 1928 he enrolled at the School of Fine Art, Athens to study painting under Constantinos Parthenis, Spyros Vikatos, Georgios Iakovides and Dimitris Biskinis, graduating in 1933. Between 1930 and 1934, he also studied with Fotis Kondoglou who introduced him to Byzantine painting. In 1935, Tsarouchis spend a year in Paris, where he studied etching at Hayterre studio; his fellow students included Max Ernest and Giacometti. -

IFK Apologismos 2015-ENG Web.Indd

THE J. F. COSTOPOULOS FOUNDATION ESTABLISHED IN 1979 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ATHENS IIFK_ApologismosFK_Apologismos 22015-ENG_web.indd015-ENG_web.indd 1 113/7/163/7/16 66:21:21 μ.μ. The J. F. Costopoulos Foundation would like to thank DDB for graciously offering the design of the Annual Report 2015. 2 IIFK_ApologismosFK_Apologismos 22015-ENG_web.indd015-ENG_web.indd 2 113/7/163/7/16 66:21:21 μ.μ. ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Portrait of John F. Costopoulos (Engraving by A. Tassos) IIFK_ApologismosFK_Apologismos 22015-ENG_web.indd015-ENG_web.indd 3 113/7/163/7/16 66:21:21 μ.μ. Brief History The J. F. Costopoulos Foundation, a non-profit charitable institution, was founded in 1979, on the occasion of the centenary of the Alpha Bank, then operating as Credit Bank, in memory of its founder John F. Costopoulos by its then Chairman, the late Spyros Costopoulos and his wife Eurydice. In accordance with its purpose, as it is stipulated by its Articles of Association and Operation, the Foundation continuously supports the safeguard and promotion of the Greek culture, literature and the arts both in Greece and abroad. 4 IIFK_ApologismosFK_Apologismos 22015-ENG_web.indd015-ENG_web.indd 4 113/7/163/7/16 66:21:21 μ.μ. The Board of Trustees Yannis S. Costopoulos Chairman Anastasia S. Costopoulos Vice-Chairman Demetrios P. Mantzounis Treasurer Thanos M. Veremis Trustee Theodoros N. Filaretos Trustee Hector P. Verykios Director Athanassios G. Efthimiopoulos Financial Services Assimina E. Strongili Magda N. Tzepkinli Secretariat Alpha Private Banking Financial Advisor Irene A. Orati Dimitra I. Tsangari Special Advisors 5 IIFK_ApologismosFK_Apologismos 22015-ENG_web.indd015-ENG_web.indd 5 113/7/163/7/16 66:21:21 μ.μ. -

Think Teen 2Nd Grade of Junior High School

001-004.qxp:01-18.qxp 11/13/08 6:16 PM Page 1 Think Teen 2nd Grade of Junior High School TEACHER’S BOOK (ΠΡΟΧΩΡΗΜΕΝΟΙ) 001-004.qxp:01-18.qxp 11/13/08 6:16 PM Page 2 ΣΥΓΓΡΑΦΕΙΣ Αλεξία Γιαννακοπούλου, Εκπαιδευτικός Γεωργία Γιαννακοπούλου, Εκπαιδευτικός Ευαγγελία Καραμπάση, Εκπαιδευτικός Θεώνη Σοφρωνά, Εκπαιδευτικός ΚΡΙΤΕΣ-ΑΞΙΟΛΟΓΗΤΕΣ Ουρανία Κοκκίνου, Μέλος ΕΕΔΙΠ 1, Πανεπιστημίου Θεσσαλίας Διονυσία Παπαδοπούλου, Σχολική Σύμβουλος Ανθούλα Φατούρου, Εκπαιδευτικός ΕΙΚΟΝΟΓΡΑΦΗΣΗ Ιωάννης Κοσμάς, Σκιτσογράφος-Εικονογράφος ΦΙΛΟΛΟΓΙΚΗ ΕΠΙΜΕΛΕΙΑ Χρυσάνθη Αυγέρου, Φιλόλογος ΥΠΕΥΘΥΝΟΣ ΤΟΥ ΜΑΘΗΜΑΤΟΣ Ιωσήφ Ε. Χρυσοχόος, Πάρεδρος ε.θ. του Παιδαγωγικού Ινστιτούτου ΥΠΕΥΘΥΝΗ ΥΠΟΕΡΓΟΥ Αλεξάνδρα Γρηγοριάδου, Τ. Πάρεδρος ε.θ. του Παιδαγωγικού Ινστιτούτου ΠΡΟΕΚΤΥΠΩΤΙΚΕΣ ΕΡΓΑΣΙΕΣ Γ´ Κ.Π.Σ. / ΕΠΕΑΕΚ II / Ενέργεια 2.2.1. / Κατηγορία Πράξεων 2.2.1.α: «Αναμόρφωση των προγραμμάτων σπουδών και συγγραφή νέων εκπαιδευτικών πακέτων» ΠΑΙΔΑΓΩΓΙΚΟ ΙΝΣΤΙΤΟΥΤΟ Δημήτριος Γ. Βλάχος Ομότιμος Καθηγητής του Α.Π.Θ. Πρόεδρος του Παιδαγωγικού Ινστιτούτου Πράξη με τίτλο: «Συγγραφή νέων βιβλίων και παραγωγή υποστηρικτικού εκπαιδευτικού υλικού με βάση το ΔΕΠΠΣ και τα ΑΠΣ για το Γυμνάσιο» Επιστημονικοί Υπεύθυνοι Έργου Αντώνιος Σ. Μπομπέτσης Σύμβουλος του Παιδαγωγικού Ινστιτούτου Γεώργιος Κ. Παληός Σύμβουλος του Παιδαγωγικού Ινστιτούτου Αναπληρωτές Επιστημονικοί Υπεύθυνοι Έργου Ιγνάτιος Ε. Χατζηευστρατίου Μόνιμος Πάρεδρος του Παιδαγωγικού Ινστιτούτου Γεώργιος Χαρ. Πολύζος Πάρεδρος ε.θ. του Παιδαγωγικού Ινστιτούτου Έργο συγχρηματοδοτούμενο 75% από το Ευρωπαϊκό Κοινωνικό Ταμείο και 25% από -

The Heritages of the Modern Greeks

The heritages of the modern Greeks PROFESSOR PETER MACKRIDGE Introduction poetry from the Mycenaeans, because they could make a fresh start with a clean slate. He presents the heritages of the What makes the heritages of the modern Greeks unique? modern Greeks as a burden – and in some cases even an They stand between East and West in the sense that they incubus – since their legacies from ancient Greece and belong neither to the Catholic and Protestant West nor to Byzantium continually threaten to dominate and the Muslim East; their Roman heritage is more eastern than overshadow them. western; yet they have been dominated by Catholic as well as Ottoman occupiers. Although I am against the concept of Greek (or any other) exceptionalism, I believe that when The nationalisation of the past foreigners deal with modern Greece they need to be sensitive The Greeks of the last 200 years have possessed ample to cultural differences, which are the result of specific historical material with which to form their national historical experiences. Especially in times of crisis such as identity. Compare the Germans, who for their ancient past the one the Greeks are going through today, the world – and have only Tacitus’ Germania, a brief and impressionistic especially Europe – needs to show sympathy and solidarity ethnography written by an outsider who warned that his with their plight. Nevertheless, this shouldn’t inhibit us aim was to comment on the Romans of his time as much as from looking critically at what Greeks – and I mean chiefly on the Germans. Tacitus left the modern Germans a great Greek intellectual and political elites – have made of their deal of leeway to invent and imagine their own antiquity. -

Performances of Ancient Greek Tragedy and Hellenikotita: the Making O F a Greek Aesthetic Style of Performance 1919-1967

Performances of Ancient Greek Tragedy and Hellenikotita: The Making o f a Greek Aesthetic Style of Performance 1919-1967 Ioanna Roilou-Panagodimitrakopoulou M.A. in Theatre Strudies M.A. in Modem Drama Submitted for a Ph.D thesis Department of Theatre Studies Lancaster University March 2003 ProQuest Number: 11003681 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003681 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Performances o f Ancient Greek Tragedy and Hellenikotita: The Making o f a Greek Aesthetic Style o f Performance 1919-1967 Ioanna Roilou-Panagodimittakopoulou M.A. in Theatre Studies, M.A. in Modem Drama Submitted for a Ph.D thesis Department a Theatre Studies Lancaster University March 2003 Abstract This t hesis s tudies t he p henomenon o f t he p roduction o ft ragedy i n G reece d uring t he period 1919-1967 in relation to the constitution of Greek culture during this period and the ideologem of hellenikotita. It argues that theatre in Greece through the productions of tragedy proposed an aesthetic framework of performances of tragedy that could be recognised as ‘purely Greek’ within which the styles of productions moved. -

ICOM Costume Newsletter 2012:2

ICOM Costume News 2012: 2 ICOM Costume News 2012: 2 17 December 2012 INTERNATIONAL COSTUME COMMITTEE COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DU COSTUME Letter from the Chair Now we can look forward to next year’s General Dear members! Conference in Rio de Janeiro, for which we have made special efforts to create a full program of This has been an exciting year for the Costume activities and papers about a wide range of Brazilian Committee, our 50th anniversary, which was costume history and specialties. The Brazilian suitably celebrated during our meeting in Brussels organizing committee has made an exceptional in October. Corrinne ter Assatouroff and Martine effort to improve our possibilities to pursue our Vrebos prepared a whirlwind of activities in sunny costume interests at the Triennial, and Brazil is in a Brussels, including visits to museums, schools and very exciting situation regarding its costume workshops, and our colleagues offered papers on collections. Our Brazilian colleagues look forward many different aspects of lace. The theme “Lace: to welcoming us next August - I hope to see many transparency and fashion” gave us the opportunity of you there! to explore many aspects of this luxurious part of our collections, from its beginnings to its newest technological expressions. The papers will be published in a Proceedings from the meeting, Katia Johansen available next spring. December 2012 Three special events marked the Committee’s 50th anniversary: a new “old” costume for Manneken Pis was made by Committee members and presented to the city of Brussels; a thematic presentation of members’ memories of 1962 was collected and shown by Alexandra Kim; and a special, elegant chocolate cake was the crowning glory of a wonderful farewell dinner. -

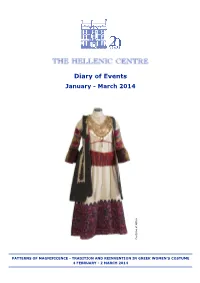

Diary of Events

Diary of Events January - March 2014 Costume of Attica of Costume PATTERNS OF MAGNIFICENCE - TRADITION AND REINVENTION IN GREEK WOMEN’S COSTUME 4 FEBRUARY - 2 MARCH 2014 JANUARY Tuesday 7 January to Thursday 30 January - Friends Room, Hellenic Centre Shadowplay A collection of paintings by Ioakim Raftopoulos, showing spontaneous gesture and experimentation with new materials, in a process to understand the specific capacity of abstraction which transcends the world of objects and representations and has an integrative and possibly anaesthetic, narcotic function. Private view on Friday 10 January, 6.30-8.30pm. For opening hours call 020 7487 5060. Supported by the Hellenic Centre. Tuesday 14 January, 7.15pm - Great Hall, Hellenic Centre Paper Icons - Orthodox Prints, A Nineteenth-Century Icon-Painters’ Collection of Greek Religious Engravings and their Role to Painters A lecture in English by Dr Claire Brisby, Courtauld Institute of Art. The lecture shows how an unknown collection of prints in a Balkan icon-painters’ archive illuminates our understanding of Greek religious engravings and painters’ use of them in their work. It discusses how their imagery explains the reasons for their production and reflects the impact of their publication in the central European centres of Vienna and Venice on their assimilation of western imagery. Particular focus is given to the fragmentary evidence of prints of two Orthodox engravings which sheds light on painters’ use of prints as sources of innovative iconography, which then leads to conclude that the role of visual prototypes should be recognised as integral part of their intended function. Free entry but please confirm attendance on 020 7563 9835 or at [email protected]. -

Teuxos 2 2008.Qxd

The Greek Theatre in the United States from the End of the 19th Century to the 21st Century Katerina Diakoumopoulou* RÉSUMÉ Cet article couvre l’activité théâtrale des immigrants Grecs aux Etats-Unis à partir de la fin du dix-neuvième siècle jusqu’à nos jours. Il souligne l’histoire de beaucoup de troupes de théâtre qui avaient fait leur apparition dans les communautés grecques d’Amerique à la fin du dix-neuvième siècle et ont connu le succès jusqu’à un déclin marquant dans la seconde décennie du vingtième siècle, déclin précipité par l’enrôlement de beaucoup de jeunes immigrants Grecs dans les Guerres Balkaniques. Le développement théâtral impressionnant, qui s’en est suivi de 1920 à 1940, et après la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, est examiné en mettant l’accent sur une variété d’aspects tels que les nombreuses troupes, d’amateurs et de professionnels et leurs répertoires, thèmes, tendances, problèmes, influences politiques, enjeux sociaux, etc., nécessaires pour comprendre le rôle et l’impact que le théâtre grec a eu jusqu’à nos jours. L’auteur note que l’on observe deux tendances particulières depuis la Seconde Guerre Mondiale: les auteurs dramatiques Américains Grecs composent leurs œuvres principalement en anglais et beaucoup d’Américains d’origine grecque de la seconde génération participent à des troupes de théâtre grecques, tandis qu’un nombre d’acteurs de la première génération ayant longtemps servi dans le théâtre sont devenus des professionnels. ABSTRACT This article covers the theatre activity of the Greek immigrants in the USA from the end of the nineteenth century until today. -

Tracking the Creative Process of Mikis Theodorakis' Electra

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojsa.html Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2020, 3(1), 1-12. ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsa.0301.01001k _________________________________________________________________________ Tracking the Creative Process of Mikis Theodorakis’ Electra: An Approach to Philosophical, Esthetical and Musical Sources of his Opera Angeliki Kordellou University of Patras, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Patras, GREECE Department of Theatrical Studies Received: 19 March 2020 ▪ Accepted: 17 May 2020 ▪ Published Online: 28 May 2020 Abstract Taking into consideration Mikis Theodorakis’ autobiography, personal notes, drafts and sketches, several scientific studies about his musical work and by means of an analytical approach of his score for Electra, it seems that tracking its creative process demands a holistic approach including various musical and extra musical parameters. For this reason the aim of this paper is to present an overview of these parameters such as: (a) aspects of the Pythagorean theory of the Universal Harmony which influenced the artist’s worldview and musical creation; (b) the artistic impact of the ancient Greek tragedy and especially of the tragic Chorus on his musical activity; (c) his long term experience in stage music, and particularly music for ancient drama performances; (d) his music for M. Cacoyannis’ movie Electra; (e) the use of musical material deriving from previous compositions of Theodorakis; and (f) the reference to musical elements originating from the Greek musical tradition. Keywords: Electra, Mikis Theodorakis, lyrical tragedy, Greek contemporary music, Greek opera. 1. Introduction The tragic fate of Electra has been the source of artistic expression since antiquity.