The Romanization of Chinese Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: the Emergence of the Yunnanese

Between Winds and Clouds Bin Yang Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: The Emergence of the Yunnanese Introduction As the state began sending soldiers and their families, predominantly Han Chinese, to Yunnan, 1 the Ming military presence there became part of a project of colonization. Soldiers were joined by land-hungry farmers, exiled officials, and profit-driven merchants so that, by the end of the Ming period, the Han Chinese had become the largest ethnic population in Yunnan. Dramatically changing local demography, and consequently economic and cultural patterns, this massive and diverse influx laid the foundations for the social makeup of contemporary Yunnan. The interaction of the large numbers of Han immigrants with the indigenous peoples created a 2 new hybrid society, some members of which began to identify themselves as Yunnanese (yunnanren) for the first time. Previously, there had been no such concept of unity, since the indigenous peoples differentiated themselves by ethnicity or clan and tribal affiliations. This chapter will explore the process that led to this new identity and its reciprocal impact on the concept of Chineseness. Using primary sources, I will first introduce the indigenous peoples and their social customs 3 during the Yuan and early Ming period before the massive influx of Chinese immigrants. Second, I will review the migration waves during the Ming Dynasty and examine interactions between Han Chinese and the indigenous population. The giant and far-reaching impact of Han migrations on local society, or the process of sinicization, that has drawn a lot of scholarly attention, will be further examined here; the influence of the indigenous culture on Chinese migrants—a process that has won little attention—will also be scrutinized. -

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

Jingjiao Under the Lenses of Chinese Political Theology

religions Article Jingjiao under the Lenses of Chinese Political Theology Chin Ken-pa Department of Philosophy, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City 24205, Taiwan; [email protected] Received: 28 May 2019; Accepted: 16 September 2019; Published: 26 September 2019 Abstract: Conflict between religion and state politics is a persistent phenomenon in human history. Hence it is not surprising that the propagation of Christianity often faces the challenge of “political theology”. When the Church of the East monk Aluoben reached China in 635 during the reign of Emperor Tang Taizong, he received the favorable invitation of the emperor to translate Christian sacred texts for the collections of Tang Imperial Library. This marks the beginning of Jingjiao (oY) mission in China. In historiographical sense, China has always been a political domineering society where the role of religion is subservient and secondary. A school of scholarship in Jingjiao studies holds that the fall of Jingjiao in China is the obvious result of its over-involvement in local politics. The flaw of such an assumption is the overlooking of the fact that in the Tang context, it is impossible for any religious establishments to avoid getting in touch with the Tang government. In the light of this notion, this article attempts to approach this issue from the perspective of “political theology” and argues that instead of over-involvement, it is rather the clashing of “ideologies” between the Jingjiao establishment and the ever-changing Tang court’s policies towards foreigners and religious bodies that caused the downfall of Jingjiao Christianity in China. This article will posit its argument based on the analysis of the Chinese Jingjiao canonical texts, especially the Xian Stele, and takes this as a point of departure to observe the political dynamics between Jingjiao and Tang court. -

Esperanto and Chinese Anarchism in the 1920S and 1930S

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Esperanto and Chinese anarchism in the 1920s and 1930s Gotelind Müller and Gregor Benton Gotelind Müller and Gregor Benton Esperanto and Chinese anarchism in the 1920s and 1930s 2006 Retrieved on 22nd April 2021 from archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2006 Zhou Enlai Zhou Zuoren Ziyou shudian Contents Introduction ..................... 5 Xuehui and Erošenko ................ 7 Anarchism and Esperanto in the late 1920s . 16 Anarchism and Esperanto in China in the 1930s 17 Conclusions ...................... 21 Bibliography ..................... 23 Glossary ........................ 25 30 3 “Wang xiangcun qu” wanguo xinyu “Wanguo xinyu”“Wo de shehui geming de yi- jian” Wu Jingheng (= Wu Zhihui) Wu Zhihui Wuxu Wuzhengfu gongchan zhuyi she “Xiandai xiju yishu zai Zhongguo de jianzhi” Xianmin Xin qingnian Xin she Xin shiji “Xinyu wenti zhi zada” Xing Xiwangzhe Xuantian Xuehui Xu Anzhen “Xu ‘Haogu zhi chengjian’” Xu Lunbo “Xu Lunbo xiansheng” “Xu ‘Pi miu’” Xu Shanguang / Liu Jianping / Xu Shanshu “Xu wanguo xinyu zhi jinbu” “Xu xinyu wenti zhi zada” Yamaga Taiji Ye Laishi Yuan Shikai “Zenyang xuanchuan zhuyi” Zhang Binglin Zhang Jiang (= Zhang Binglin) Zhang Jingjiang Zhang Qicheng Zheng Bi’an Zheng Chaolin Zheng Peigang Zheng Taipu “Zhishi jieji de shiming” “Zhongguo gudai wuzhengfuzhuyi chao zhi yipie” Zhongguo puluo shijieyuzhe lianmeng Zhongguo wuzhengfuzhuyi he Zhongguo shehuidang 29 Min Esperanto in China and among the Chinese diaspora was for Minbao long periods closely linked with anarchism. This article looks Ming Minguo ribao at the history of the Chinese Esperanto movement after the Minsheng repatriation of anarchism to China in the 1910s. It examines Minshengshe jishilu Esperanto’s political connections in the Chinese setting and Miyamoto Masao the arguments used by its supporters to promote the language. -

In Search of an Effective Romanized Transcription System for Learning Chinese Pronunciation Background

In Search of an Effective Romanized Transcription System for Learning Chinese Pronunciation Background. Learning to pronounce Chinese characters has always been a challenge for native English speakers for two reasons: 1) the Chinese language contains certain sounds that are not present in the English language and 2) due to the logographic nature of Chinese, romanized transcription systems have been developed to aid in the learning of Chinese pronunciation, however, most romanized transcription systems do not accurately represent Chinese sounds when read by native English speakers. In our present global community foreign language must be taught in methods that most efficiently reflect the needs of the target language learner. To adequately address these needs, Chinese language pedagogy in America and possibly other English speaking countries must shift to accommodate the target’s learner characteristics which includes developing a curriculum of learning Chinese pronunciation not by associating Chinese sounds with misrepresented Latin letters, but by allowing the transcription system flow naturally from the learner’s language. Research Procedure. Noticing this hindrance from first hand experience and from other native English speakers in several elementary Chinese language classes, I chose to examine the five most popular romanized transcription systems for Chinese and test them on native English speakers with no prior knowledge of Chinese to see which one(s) produced the most standard pronunciation. The Scripts chosen were: Hanyu Pinyin, -

The Creative Artist: a Journal of Theatre and Media Studies, Vol 13, 2, 2017

The Creative Artist: A Journal of Theatre and Media Studies, Vol 13, 2, 2017 MANDARIN CHINESE PINYIN: PRONUNCIATION, ORTHOGRAPHY AND TONE Sunny Ifeanyi Odinye, PhD Department of Igbo, African and Asian Studies Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Pinyin is essential and most fundamental knowledge for all serious learners of Mandarin Chinese. If students are learning Mandarin Chinese, no matter if they are beginners or advanced learners, they should be aware of paramount importance of Pinyin. Good knowledge in Pinyin can greatly help students express themselves more clearly; it can also help them in achieving better listening and reading comprehension. Before learning how to read, write, or pronounce Chinese characters, students must learn pinyin first. This study aims at highlighting the importance of Pinyin and its usage in Mandarin for any students learning Mandarin Chinese. The research work adopts descriptive research method. The work is divided into introduction, body and conclusion. 1. INTRODUCTION Pinyin (spelled sounds) has vastly increased literacy throughout China and beyond; eased the classroom agonies of foreigners studying Mandarin Chinese; afforded the blind a way to read the language in Braille; facilitated the rapid entry of Chinese on computer keyboards and cell phones. "About one billion Chinese citizens have mastered pinyin, which plays an important role in both Chinese language education and international communication," said Wang Dengfeng, vice-chairman of the National Language Committee and director of language department of the Education Ministry. "Hanyu Pinyin not only belongs to China but also belongs to the world. It is now everywhere in our daily lives," Wang said, "Pinyin will continue playing an important role in the modernization of China." (Xinhua News, 2008). -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

Ocelot Mandarin Oral Recognition Test Roderick Gammon Kapi'olani

Ocelot Mandarin Oral Recognition Test Roderick Gammon Kapi’olani Community College February 16, 2004ß Abstract The Ocelot Mandarin Oral Recognition Test is a diagnostic test that measures a student’s ability to match spoken Chinese syllables to a romanization. Analogous to using a Romanized dictionary index, test items are multimedia multiple-choice with an audio prompt and a selection of textual romanizations. The test is organized into subunits focused on different features in a formal linguistic construct of a Mandarin syllable (Yao et al., 1997). The test is computer adaptive and allows for criterion referenced (Brown and Hudson, 2002) item banking (Brown, 1997). After a literature review, this paper describes the structure and piloting of the test. Introduction The Ocelot Mandarin Oral Recognition Test (MORT) measures recognition of Mandarin Chinese oral syllables by interpreting subject performance relevant to a linguistic feature system. Implemented as a Flash (2004 MX) applet, the test is computer adaptive and algorithmically generates items at runtime. The test was created as a member of a set of computer assisted language-learning (CALL) materials modeled around a particular course of study using the Integrated Chinese (Yao et al., 1997) textbooks. This introduction reviews literature regarding Mandarin romanization, language testing, and CALL design. Following that review the introduction recasts the MORT and its pilot study in terms for research questions raised by the literature review. The MORT instrument and its piloting are then described. The paper concludes with a consideration of further avenues of study. Mandarin Mandarin Chinese, with increasing regularity since the mid-20th century, been transcribed using the Pinyin Romanization method (Ramsey, 1987). -

China's Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916

Illustrations iii Michael Keevak Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 2008 ISBN 978-962-209-895-4 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Secure On-line Ordering http://www.hkupress.org Printed and bound by Lammar Offset Printing Ltd., Hong Kong, China. Hong Kong University Press is honoured that Xu Bing, whose art explores the complex themes of language across cultures, has written the Press’s name in his Square Word Calligraphy. This signals our commitment to cross-cultural thinking and the distinctive nature of our English-language books published in China. “At first glance, Square Word Calligraphy appears to be nothing more unusual than Chinese characters, but in fact it is a new way of rendering English words in the format of a square so they resemble Chinese characters. Chinese viewers expect to be able to read Square Word Calligraphy but cannot. Western viewers, however are surprised to find they can read it. Delight erupts when meaning is unexpectedly revealed.” — Britta Erickson, The Art of Xu Bing Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments xi Prologue The Story of a Stone 1 1 A Stone Discovered 5 2 The Century of Kircher 29 3 Eighteenth-Century Problems and Controversies 61 4 The Return of the Missionaries 89 Epilogue The Da Qin Temple 129 Notes 143 Works Cited 169 Index 187 Illustrations vii Illustrations 11. -

Romanization Examples

Romanization examples Each title of a language or a writing system is followed by a note on the appropriate romanization system used (UN = United Nations, BGN/PCGN = US Board on Geographic Names and Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use) Amharic [UN 1967, I/17] Lao [national 1966] ኢትዮጵያ Ityop’ya [ Ethiopia ], አዲስ አበባ Addis Abe ̱ ba ລາວ Lao [ Laos ], ວງຈັ ນ Viangchan Arabic [UN 1972, II/8] Macedonian Cyrillic [UN 1977, III/11] Jaz īrat al-‘Arab [ Arabian Peninsula ] Скопје Skopje, Битола Bitola ز رة ارب Armenian [BGN/PCGN 1981] Malayalam [UN 1972, II/11; 1977, III/12] Հայաստան Hayastan [ Armenia ], Երևան Yerevan Kera ḷaṁ, Tiruvanantapura ṁ Assamese [UN 1972, II/11; 1977, III/12] Maldivian [national 1987] Asam [ Assam ], Dichhapura [ Dispur ] ޖ އ ރ ހ ވ ދ Dhivehi Raajje [ Maldives ], ލ މ Maale Bengali [UN 1972, II/11; 1977, III/12] Marathi [UN 1972, II/11; 1977, III/12] Bāṁ lādesh, Dhaka महारा Mah ārāṣhṭra, मुंबई Mu ṁba ī Bulgarian [UN 1977, III/10] Mongolian (Cyrillic) [BGN/PCGN 1964] Република България Republika B ǎlgarija Монгол улс Mongol uls, Улаанбаатар Ulaanbaatar Burmese [BGN/PCGN 1970] Nepalese [UN 1972, II/11; 1977, III/12] ြမန်မာ Myanma, ရန်ကန် Yangôn नेपाल Nepāl, काठमाड Kāṭhm āḍau ṁ [Kathmandu ] Byelorussian [national 2007] Беларусь Bielaru ś, Минск Minsk Oriya [UN 1972, II/11; 1977, III/12] Chinese [UN 1977, III/8] Oṙish ā, Bhubaneshbar 中国 Zhongguo, 北京 Beijing Pashto [BGN/PCGN 1968] XQY Kābulل ,Afgh ānist ān اQRSTQUVن [Dzongkha [national 1997 འག་ལ Drukyuel [Bhutan ], ཐིམ་ Thimphu Persian -

Herbert Allen Giles (1845-1935) and Pu Songling’S Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio

Herbert Allen Giles (1845-1935) and Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio John Minford Culture & Translation Series Lecture Three Hang Seng Management College 27 February 2016 It must however always be borne in mind that translators are but traitors at the best, and that translations may be moonlight and water while the originals are sunlight and wine. — Herbert Giles, 16 October 1883 Dear Land of Flowers, forgive me! — that I took These snatches from thy glittering wealth of song, And twisted to the uses of a book Strains that to alien harps can ne’er belong. Thy gems shine purer in their native bed Concealed, beyond the pry of vulgar eyes; Until, through labyrinths of language led, The patient student grasps the glowing prize. Yet many, in their race toward other goals, May joy to feel, albeit at second-hand, Some far faint heart-throb of poetic souls Whose breath makes incense in the Flowery Land. — Herbert Giles, October 1898, Cambridge Chronology Born 1845, son of John Allen Giles (1808-1884), unconventional Anglican priest Educated at Charterhouse School 1867: Entered China Consular Service, stationed in Peking trained as Student Interpreter. Served in numerous posts in the Treaty Ports (Tientsin, Ningpo, Hankow, Swatow, Amoy), including Taiwan — the China Coast In Amoy involved in setting up the Freemasons Lodge 1892-1893: retired to Britain 1897: became Professor of Chinese (successor to Thomas Wade) at Cambridge until 1928 His children: Bertram, Valentine, Lancelot, Edith, Mable, and Lionel Giles. Publications A Chinese-English dictionary (1892); a Biographical Dictionary (1898); a Glossary of Reference (1878); complete translation of Zhuangzi 莊子 — Chuang-Tzu, Mystic, Moralist and Social Reformer (1889) Anthologies of Verse and Prose (1923) Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio 聊齋志異, 1880, revised 1908, 1916, 1925. -

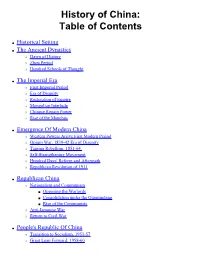

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century.