Download This Paper in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINMAP Région Du Centre SERVICES DECONCENTRES REGIONAUX ET DEPARTEMENTAUX

MINMAP Région du Centre SERVICES DECONCENTRES REGIONAUX ET DEPARTEMENTAUX N° Désignation des MO/MOD Nbre de Marchés Montant des Marchés N° page 1 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 19 2 278 252 000 4 Département de la Haute Sanaga 2 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 291 434 000 7 3 COMMUNE DE BIBEY 2 77 000 000 8 4 COMMUNE DE LEMBE YEZOUM 8 119 000 000 8 5 COMMUNE DE MBANDJOCK 3 50 000 000 10 6 COMMUNE DE MINTA 5 152 500 000 10 7 COMMUNE DE NANGA-EBOKO 12 139 500 000 11 8 COMMUNE DE NKOTENG 5 76 000 000 13 9 COMMUNE DE NSEM 1 27 000 000 13 TOTAL 42 932 434 000 Département de la Lekié 10 Services déconcentrés départementaux 8 268 357 000 14 11 COMMUNE DE BATCHENGA 2 35 000 000 15 12 COMMUNE DE LOBO 8 247 000 000 15 13 COMMUNE DE MONATELE 11 171 500 000 16 14 COMMUNE DE SA'A 16 384 357 000 18 15 COMMUNE D'ELIG-MFOMO 7 125 000 000 20 16 COMMUNE D'EVODOULA 9 166 250 000 21 17 COMMUNE D'OBALA 14 223 500 000 22 18 COMMUNE D'OKOLA 22 752 956 000 24 19 COMMUNE D’EBEBDA 6 93 000 000 27 TOTAL 103 2 466 920 000 Département du Mbam et Inoubou 20 Services déconcentrés départementaux 4 86 000 000 28 21 COMMUNE DE BAFIA 5 75 500 000 28 22 COMMUNE DE BOKITO 12 213 000 000 29 23 COMMUNE DE KIIKI 4 134 000 000 31 24 COMMUNE DE KONYAMBETA 6 155 000 000 32 25 COMMUNE DE DEUK 2 77 000 000 33 26 COMMUNE DE MAKENENE 3 17 000 000 33 27 COMMUNE DE NDIKINIMEKI 4 84 000 000 34 28 COMMUNE D'OMBESSA 5 91 000 000 34 29 COMMUNE DE NITOUKOU 6 83 000 000 35 TOTAL 51 1 015 500 000 MINMAP/DIVISION DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI DES MARCHES PUBLICS Page 1 de 88 N° Désignation -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Nyong Et Kellé

OFFICE 3j;E LA RECHERCHE REPUBLIQUE FEDERALE SCIEhTBFIQUE ET TECHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE ORSTOM DE YAOUNDE DICTIO..NN,AIREDES VILLAGES DU NYONG ET KELLE (2' 6dition) D'après la documentation réuriie par la Sectioiî de Géographie de I'ORSTOM1 REPERTOIRE GEOÇRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE No 8 SH. nu 57 Avril 1970 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHlQUE DU CAMEROUN Fasc. I Tableau de Io population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. NO 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia-et-Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. NO 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des villages de la Haute-Sanaga, 44 p. Août 1965 SH. No 50 (2' éd. 1969 1 ' Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des vtllages du Nyong-et-Mfoumou, 49 p. Oct'obre 1965 SH. NO 24 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire d,es villages du Nyon;-etspo 45 p. Novembre t965 SH. No 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionneire. des villages du Ntsm 102 p. WC. 1965. SH. NO46 (2' édition Juin 1969 1 d 1% Fasc. 7 ~ictionnair. der village; de la Mefou 100; P. Jahvier 1966 SH. NOk7 1 1 1 , Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des iillagei du Nyong-et-Ksllé, 5 1 p. Fév: 1b66 SH. 5712' éd. avril 1970 1 1 Fasc. 9 Dictionnsire ;des villages de la Lékié 7 1 p. Merr 1966~~.29. Fasc. 10 ~iction&re des villages de Kr*i 29 p. \ Man- 1965SH. Irp W (2' Bdit. octobre 1969 1 ' 5 ' , Fasc. I I Dictionnaire;diss vlllsg~sdu Mba.r(--60 p. %i 1966 Sç-! W 52 t2' édit. sept. 1969) 1 l Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire de* vfllqgbr de BQU~~~-N~O~O34 p. -

GE84/275 BR IFIC Nº 2893 Section Spéciale Special Section

Section spéciale Index BR IFIC Nº 2893 Special Section GE84/275 Sección especial Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Date/Fecha : 16.04.2019 Expiry date for comments / Fecha limite para comentarios / Date limite pour les commentaires : 25.07.2019 Description of Columns / Descripción de columnas / Description des colonnes Intent Purpose of the notification Propósito de la notificación Objet de la notification 1a Assigned frequency Frecuencia asignada Fréquence assignée 4a Name of the location of Tx station Nombre del emplazamiento de estación Tx Nom de l'emplacement de la station Tx B Administration Administración Administration 4b Geographical area Zona geográfica Zone géographique 4c Geographical coordinates Coordenadas geográficas Coordonnées géographiques 6a Class of station Clase de estación Classe de station 1b Vision / sound frequency Frecuencia de portadora imagen/sonido Fréquence image / son 1ea Frequency stability Estabilidad de frecuencia Stabilité de fréquence 1e carrier frequency offset Desplazamiento de la portadora Décalage de la porteuse 7c System and colour system Sistema de transmisión / color Système et système de couleur 9d Polarization Polarización Polarisation 13c Remarks Observaciones Remarques 9 Directivity Directividad -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DU CENTRE EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES N° Désignation des MO/MOD Nbre de Marchés Montant des Marchés N°Page 1 Services déconcentrés Régionaux 17 736 645 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine de Yaoundé 62 10 459 000 000 5 Département de la Haute Sanaga 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 2 24 000 000 10 4 Commune de Bibey 12 389 810 000 10 5 Commune de Lembe Yezoum 17 397 610 000 11 6 Commune de Mbandjock 12 214 000 000 12 7 Commune de Minta 8 184 500 000 12 8 Commune de Nanga Ebogo 21 372 860 000 13 9 Commune de Nkoteng 12 281 550 000 14 10 Commune de Nsem 5 158 050 000 15 TOTAL 89 2 022 380 000 Département de la Lekié 11 Services déconcentrés départementaux 9 427 000 000 16 12 Commune de Batchenga 8 194 000 000 17 13 Commune d'Ebebda 10 218 150 000 18 14 Commune d'Elig-Mfomo 8 174 000 000 19 15 Commune d'Evodoula 10 242 531 952 20 16 Commune de Lobo 11 512 809 000 21 17 Commune de Monatélé 12 288 500 000 22 18 commune d'Obala 11 147 000 000 23 19 commune d'Okola 14 363 657 000 24 20 commune de Sa'a 17 319 500 000 25 TOTAL 110 2 887 147 952 Département du Mbam et Inoubou 21 Services déconcentrés départementaux 6 144 385 000 27 22 Commune Bafia 13 213 500 000 27 23 Commune de Bokito 9 167 500 000 28 24 Commune de DEUK 17 379 500 000 29 25 Commune Kiiki 10 285 000 000 30 26 Commune Konyambeta 12 295 -

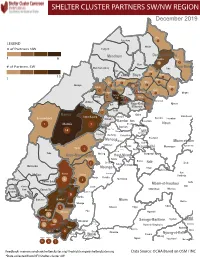

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Land Use and Land Cover Changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 18 February 2020 Land Use and Land Cover changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon Tchindjang Mesmin; Saha Frédéric, Voundi Eric, Mbevo Fendoung Philippes, Ngo Makak Rose, Issan Ismaël and Tchoumbou Frédéric Sédric * Correspondence: Tchindjang Mesmin, Lecturer, University of Yaoundé 1 and scientific Coordinator of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Saha Frédéric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and project manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Voundi Eric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and technical manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Mbevo Fendoung Philippes PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and internship at University of Liège Belgium; [email protected] Ngo Makak Rose, MSC, GIS and remote sensing specialist at Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring; [email protected] Issan Ismaël, MSC and GIS specialist, [email protected] Tchoumbou Kemeni Frédéric Sédric MSC, database specialist, [email protected] Abstract: Cameroon territory is experiencing significant land use and land cover (LULC) changes since its independence in 1960. But the main relevant impacts are recorded since 1990 due to intensification of agricultural activities and urbanization. LULC effects and dynamics vary from one region to another according to the type of vegetation cover and activities. Using remote sensing, GIS and subsidiary data, this paper attempted to model the land use and land cover (LULC) change in the Centre Region of Cameroon that host Yaoundé metropolis. The rapid expansion of the city of Yaoundé drives to the land conversion with farmland intensification and forest depletion accelerating the rate at which land use and land cover (LULC) transformations take place. -

Predicted Distribution and Burden of Podoconiosis in Cameroon

Predicted distribution and burden of podoconiosis in Cameroon. Supplementary file Text 1S. Formulation and validation of geostatistical model of podoconiosis prevalence Let Yi denote the number of positively tested podoconiosis cases at location xi out of ni sample individuals. We then assume that, conditionally on a zero-mean spatial Gaussian process S(x), the Yi are mutually independent Binomial variables with probability of testing positive p(xi) such that ( ) = + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) 1 ( ) � � 0 1 2 3 4 5 − + ( ) + ( ) 6 where the explanatory in the above equation are, in order, fraction of clay, distance (in meters) to stable light (DSTL), distance to water bodies (DSTW), elevation (E), precipitation(Prec) (in mm) and fraction of silt at location xi. We model the Gaussian process S(x) using an isotropic and stationary exponential covariance function given by { ( ), ( )} = { || ||/ } 2 ′ − − ′ Where || ||is the Euclidean distance between x and x’, is the variance of S(x) and 2 is a scale − pa′rameter that regulates how fast the spatial correlation decays to zero for increasing distance. To check the validity of the adopted exponential correlation function for the spatial random effects S(x), we carry out the following Monte Carlo algorithm. 1. Simulate a binomial geostatistical data-set at observed locations xi by plugging-in the maximum likelihood estimates from the fitted model. 2. Estimate the unstructured random effects Zi from a non-spatial binomial mixed model obtained by setting S(x) =0 for all locations x. 3. Use the estimates for Zi from the previous step to compute the empirical variogram. 4. Repeat steps 1 to 3 for 10,000 times. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages De La Lekié

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE ETTECHNIQUE OUTRE-MER Il REPUBLIQUE FEDERALE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DE LA lEKIE 1 SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIiIQUE REPUBLIQUE FEDERÀLE ET TECHNIQUE OUTRE-YiliR DU CAIjJ.EROUN -=-:-=-=-=-=- -=-=--=- CENTRE ORS T 0 IiI DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DE LA LEKIE -=-=-=-=-=-=-:-:- (2ème édition) MARS 1971 S.H. nO 75 Z7ABLE DL::> fdATIERES -:-=-=-:;::-=-=_.. =-=-=-=- Introduction .0. 0 0 0 Il 0 0 0 •• 000 0 Il 0 Il 0 0 Il • 0 • 0 ••• 0 0 a 0 0 • 0 0 0 •• 000 Note sur le rep8rage des villages •..••..•.....••.••..•. l et II Liste des abréviations •..••..••.••••.•••..•••...••.••.. III Divisions administratives ...•••••......•••.•..••••..•.• IV Tableau de la population du département •.•.....•••..... V et VI Liste des villages par groupements : Arrondissement de r·,Ionatélé ••......•..••.•.....•.•.•. VII Arrondissement d vEvodoula •.•...........•...•.•••...• VII et VIII Arrondissement d v Obala .••....•.........•.••..•••...• VIII et IX Arrondissement dVOkola •••••....•••.................. IX et X Arrondi s sernent de Saa •....•.........•.........•..... X et XI Dictionnaire des villages ...••.•..•................. 1 Carte du département de la Lékié ••............•••. (hors texte) * * * L7 N T R 0 DUC T ION Le recensement utilisé pour ce nouveau dictionnaire de la Lékié est celùi de 1966/57.La localisation des villages a été entièrement revue par les géographes de la section à à l'occasion de leurs travaux en cours sur la région. Nous avons ainsi pu dresser la carte hors-texte à l'échelle de 1/100.0008 beaucoup plus précise que précédemment. Les informations concernant les équipements économiques et sociaux ont été recueillies auprès des autorités administra tives locales avec la collaboration de Hubert Elingui aide géographe. Nous serions reconnaissant aux utilisateurs de nous signaler les éventuelles erreurs ou omissions qu'ils pourraient relever dans ce dictionnaire. -

CAMEROON Country Operational Plan COP 2017 Strategic Direction Summary April 17, 2017

CAMEROON Country Operational Plan COP 2017 Strategic Direction Summary April 17, 2017 1 | Page Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 2.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 2.2 Investment profile 2.3 Sustainability Profile 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 2.5 Stakeholder engagement 3.0 Geographic and population prioritization 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-up Locations and Populations 4.1 Targets for scale-up locations and populations 4.2 Priority population prevention 4.3 Voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) 4.4 Preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) 4.5 HIV testing and counseling (HTS) 4.6 Facility and community-based care and support 4.7 TB/HIV 4.8 Adult treatment 4.9 Pediatric Treatment 4.10 OVC 4.11 Addressing COP17 Technical Considerations 4.12 Commodities 4.13 Collaboration, Integration and Monitoring 5.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Attained and Sustained Locations and Populations 5.1 Targets for scale-up locations and populations 5.2 Priority population prevention 5.3 Voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) 5.4 Preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) 5.5 HIV testing and counseling (HTS) 5.6 Facility and community-based care and support 5.7 TB/HIV 5.8 Adult treatment 5.9 Pediatric Treatment 5.10 OVC 5.11 Establishing service packages to meet targets in attained and sustained districts 5.12 Commodities 5.13 Collaboration, Integration and Monitoring 2 | Page 6.0 Program -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

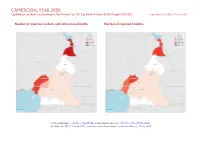

CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 March 2021

CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 572 313 669 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 386 198 818 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 2 Strategic developments 204 1 1 Protests 131 2 2 Methodology 3 Riots 63 28 38 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 43 14 62 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1399 556 1590 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 CAMEROON, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Rapport De Presentation Des Resultats Definitifs Resume

RAPPORT DE PRESENTATION DES RESULTATS DEFINITIFS RESUME Combien sommes-nous au Cameroun en novembre § catégorie 2 : les régions dont l’effectif de la population 2005, plus de 18 ans après notre 2e Recensement se situe entre 1 et 2 millions d’habitants. Ce sont Général de la Population et de l’Habitat effectué en avril dans l’ordre d’importance : les régions du Nord- 1987 ? Ouest (1 728 953 habitants), de l’Ouest (1 720 047 Dix-sept millions quatre cent soixante-trois mille habitants), du Nord (1 687 959 habitants) et du Sud- huit cent trente-six (17 463 836) Ouest (1 316 079 habitants) ; § catégorie 3 : les régions ayant chacune moins C’est là une tendance démographique qui confirme le d’un million d’habitants. Ce sont dans l’ordre : les maintien d’un fort potentiel humain dans notre pays, avec régions de l’Adamaoua (884 289 habitants), de l’Est un taux annuel moyen de croissance démographique (771 755 habitants) et du Sud (634 655 habitants). évalué à 2,8 % au cours de la période 1987-2005. Entre le premier recensement effectué en avril 1976, où le D’avril 1987 à novembre 2005, la densité de population Cameroun comptait 7 663 246 habitants et le troisième du Cameroun est passée de 22,6 habitants au kilomètre recensement réalisé en novembre 2005, la population du carré à 37,5. En 2005, cet indicateur connaît de grandes Cameroun a plus que doublé : son effectif a été multiplié variations géographiques : les régions les plus densément par 2,27 précisément. La persistance de ces tendances peuplées sont par ordre d’importance : le Littoral (124 2 2 démographiques fortes, si elles sont maintenues, situera habitants/km ) et l’Ouest (123,8 habitants/km ), tandis l’effectif de la population du Cameroun à 18,9 millions que celles qui le sont le moins, sont : l’Adamaoua 2 2 au 1er janvier 2009, 19,4 millions au 1er janvier 2010 et (13,9 habitants/km ), le Sud (13,4 habitants/km ) et l’Est 2 21,9 millions au 1er janvier 2015.