Chapter 32 FOREIGN BODIES of the HEAD, NECK, and SKULL BASE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework Ages Birth to Five

Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework Ages Birth to Five 2015 R U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Office of Head Start Office of Head Start | 8th Floor Portals Building, 1250 Maryland Ave, SW, Washington DC 20024 | eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov Dear Colleagues: The Office of Head Start is proud to provide you with the newly revisedHead Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages Birth to Five. Designed to represent the continuum of learning for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, this Framework replaces the Head Start Child Development and Early Learning Framework for 3–5 Year Olds, issued in 2010. This new Framework is grounded in a comprehensive body of research regarding what young children should know and be able to do during these formative years. Our intent is to assist programs in their efforts to create and impart stimulating and foundational learning experiences for all young children and prepare them to be school ready. New research has increased our understanding of early development and school readiness. We are grateful to many of the nation’s leading early childhood researchers, content experts, and practitioners for their contributions in developing the Framework. In addition, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Head Start Research and Evaluation and the National Centers of the Office of Head Start, especially the National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning (NCQTL) and the Early Head Start National Resource Center (EHSNRC), offered valuable input. The revised Framework represents the best thinking in the field of early childhood. The first five years of life is a time of wondrous and rapid development and learning.The Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages Birth to Five outlines and describes the skills, behaviors, and concepts that programs must foster in all children, including children who are dual language learners (DLLs) and children with disabilities. -

Introduction to Arthropod Groups What Is Entomology?

Entomology 340 Introduction to Arthropod Groups What is Entomology? The study of insects (and their near relatives). Species Diversity PLANTS INSECTS OTHER ANIMALS OTHER ARTHROPODS How many kinds of insects are there in the world? • 1,000,0001,000,000 speciesspecies knownknown Possibly 3,000,000 unidentified species Insects & Relatives 100,000 species in N America 1,000 in a typical backyard Mostly beneficial or harmless Pollination Food for birds and fish Produce honey, wax, shellac, silk Less than 3% are pests Destroy food crops, ornamentals Attack humans and pets Transmit disease Classification of Japanese Beetle Kingdom Animalia Phylum Arthropoda Class Insecta Order Coleoptera Family Scarabaeidae Genus Popillia Species japonica Arthropoda (jointed foot) Arachnida -Spiders, Ticks, Mites, Scorpions Xiphosura -Horseshoe crabs Crustacea -Sowbugs, Pillbugs, Crabs, Shrimp Diplopoda - Millipedes Chilopoda - Centipedes Symphyla - Symphylans Insecta - Insects Shared Characteristics of Phylum Arthropoda - Segmented bodies are arranged into regions, called tagmata (in insects = head, thorax, abdomen). - Paired appendages (e.g., legs, antennae) are jointed. - Posess chitinous exoskeletion that must be shed during growth. - Have bilateral symmetry. - Nervous system is ventral (belly) and the circulatory system is open and dorsal (back). Arthropod Groups Mouthpart characteristics are divided arthropods into two large groups •Chelicerates (Scissors-like) •Mandibulates (Pliers-like) Arthropod Groups Chelicerate Arachnida -Spiders, -

Medical Terminology Abbreviations Medical Terminology Abbreviations

34 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS The following list contains some of the most common abbreviations found in medical records. Please note that in medical terminology, the capitalization of letters bears significance as to the meaning of certain terms, and is often used to distinguish terms with similar acronyms. @—at A & P—anatomy and physiology ab—abortion abd—abdominal ABG—arterial blood gas a.c.—before meals ac & cl—acetest and clinitest ACLS—advanced cardiac life support AD—right ear ADL—activities of daily living ad lib—as desired adm—admission afeb—afebrile, no fever AFB—acid-fast bacillus AKA—above the knee alb—albumin alt dieb—alternate days (every other day) am—morning AMA—against medical advice amal—amalgam amb—ambulate, walk AMI—acute myocardial infarction amt—amount ANS—automatic nervous system ant—anterior AOx3—alert and oriented to person, time, and place Ap—apical AP—apical pulse approx—approximately aq—aqueous ARDS—acute respiratory distress syndrome AS—left ear ASA—aspirin asap (ASAP)—as soon as possible as tol—as tolerated ATD—admission, transfer, discharge AU—both ears Ax—axillary BE—barium enema bid—twice a day bil, bilateral—both sides BK—below knee BKA—below the knee amputation bl—blood bl wk—blood work BLS—basic life support BM—bowel movement BOW—bag of waters B/P—blood pressure bpm—beats per minute BR—bed rest MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS 35 BRP—bathroom privileges BS—breath sounds BSI—body substance isolation BSO—bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy BUN—blood, urea, nitrogen -

BIOSC 0805: the HUMAN BODY Department of Biological Sciences University of Pittsburgh

Syllabus: Biosc 0805, The Human Body BIOSC 0805: THE HUMAN BODY Department of Biological Sciences University of Pittsburgh Faculty Zuzana Swigonova, Ph.D. Office: 356 Langley Hall (Third floor, the bridge between Clapp and Langley halls) tel.: 412-624-3288; email: [email protected] Office hours Office hours: Mondays 10:00 – 11:30 AM, 356 Langley Hall Wednesdays 1:00 – 2:30 PM, 356 Langley Hall Office hours by appointment can be arranged by email. Lecture Time Tuesdays & Thursdays, 2:30 – 3:45 PM, 169 Crawford Hall Course objectives This is a course in human biology and physiology for students not majoring in biology. The goal is to provide students with an understanding of fundamental principles of life with an emphasis on the human body. We will start by covering basic biochemistry and cell biology and then move on to the structure and function of human organ systems. An essential part of the course is a discussion of health issues of general interest, such as infectious, autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases; asthma and allergy; nutrition and health; stem cells research and cloning; and methods of contraception and reproductive technologies. Textbook • Biology. A guide to the natural world, by David Krogh. Pearson, Benjamin Cummings Publishing Company. (ISBN#:0-558-65495-9). This is custom made textbook that includes only the parts of the original edition that are covered in the course. It is available in the Pitt bookstore. • You can also use the full 4th or 3rd edition, however, be aware that the chapters in earlier editions are rearranged in a different order and may be lacking some parts included in the later edition. -

The Development of a Whole-Head Human Finite- Element Model for Simulation of the Transmission of Bone-Conducted Sound

The development of a whole-head human finite- element model for simulation of the transmission of bone-conducted sound You Chang, Namkeun Kim and Stefan Stenfelt Journal Article N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: You Chang, Namkeun Kim and Stefan Stenfelt, The development of a whole-head human finite-element model for simulation of the transmission of bone-conducted sound, Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 2016. 140(3), pp.1635-1651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1121/1.4962443 Copyright: Acoustical Society of America / Nature Publishing Group http://acousticalsociety.org/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-133011 The development of a whole-head human finite-element model for simulation of the transmission of bone-conducted sound You Chang1), Namkeun Kim2), and Stefan Stenfelt1) 1) Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden 2) Division of Mechanical System Engineering, Incheon National University, Incheon, Korea Running title: whole-head finite-element model for bone conduction 1 Abstract A whole head finite element model for simulation of bone conducted (BC) sound transmission was developed. The geometry and structures were identified from cryosectional images of a female human head and 8 different components were included in the model: cerebrospinal fluid, brain, three layers of bone, soft tissue, eye and cartilage. The skull bone was modeled as a sandwich structure with an inner and outer layer of cortical bone and soft spongy bone (diploë) in between. The behavior of the finite element model was validated against experimental data of mechanical point impedance, vibration of the cochlear promontories, and transcranial BC sound transmission. -

Head and Neck

DEFINITION OF ANATOMIC SITES WITHIN THE HEAD AND NECK adapted from the Summary Staging Guide 1977 published by the SEER Program, and the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Fifth Edition published by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging. Note: Not all sites in the lip, oral cavity, pharynx and salivary glands are listed below. All sites to which a Summary Stage scheme applies are listed at the begining of the scheme. ORAL CAVITY AND ORAL PHARYNX (in ICD-O-3 sequence) The oral cavity extends from the skin-vermilion junction of the lips to the junction of the hard and soft palate above and to the line of circumvallate papillae below. The oral pharynx (oropharynx) is that portion of the continuity of the pharynx extending from the plane of the inferior surface of the soft palate to the plane of the superior surface of the hyoid bone (or floor of the vallecula) and includes the base of tongue, inferior surface of the soft palate and the uvula, the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars, the glossotonsillar sulci, the pharyngeal tonsils, and the lateral and posterior walls. The oral cavity and oral pharynx are divided into the following specific areas: LIPS (C00._; vermilion surface, mucosal lip, labial mucosa) upper and lower, form the upper and lower anterior wall of the oral cavity. They consist of an exposed surface of modified epider- mis beginning at the junction of the vermilion border with the skin and including only the vermilion surface or that portion of the lip that comes into contact with the opposing lip. -

Comparison of Cadaveric Human Head Mass Properties: Mechanical Measurement Vs

12 INJURY BIOMECHANICS RESEARCH Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Workshop Comparison of Cadaveric Human Head Mass Properties: Mechanical Measurement vs. Calculation from Medical Imaging C. Albery and J. J. Whitestone This paper has not been screened for accuracy nor refereed by any body of scientific peers and should not be referenced in the open literature. ABSTRACT In order to accurately simulate the dynamics of the head and neck in impact and acceleration environments, valid mass properties data for the human head must exist. The mechanical techniques used to measure the mass properties of segmented cadaveric and manikin heads cannot be used on live human subjects. Recent advancements in medical imaging allow for three-dimensional representation of all tissue components of the living and cadaveric human head that can be used to calculate mass properties. A comparison was conducted between the measured mass properties and those calculated from medical images for 15 human cadaveric heads in order to validate this new method. Specimens for this study included seven female and eight male, unembalmed human cadaveric heads (ages 16 to 97; mean = 59±22). Specimen weight, center of gravity (CG), and principal moments of inertia (MOI) were mechanically measured (Baughn et al., 1995, Self et al., 1992). These mass properties were also calculated from computerized tomography (CT) data. The CT scan data were segmented into three tissue types - brain, bone, and skin. Specific gravity was assigned to each tissue type based on values from the literature (Clauser et al., 1969). Through analysis of the binary volumetric data, the weight, CG, and MOIs were determined. -

1 Introduction to Cell Biology

1 Introduction to cell biology 1.1 Motivation Why is the understanding of cell mechancis important? cells need to move and interact with their environment ◦ cells have components that are highly dependent on mechanics, e.g., structural proteins ◦ cells need to reproduce / divide ◦ to improve the control/function of cells ◦ to improve cell growth/cell production ◦ medical appli- cations ◦ mechanical signals regulate cell metabolism ◦ treatment of certain diseases needs understanding of cell mechanics ◦ cells live in a mechanical environment ◦ it determines the mechanics of organisms that consist of cells ◦ directly applicable to single cell analysis research ◦ to understand how mechanical loading affects cells, e.g. stem cell differentation, cell morphology ◦ to understand how mechanically gated ion channels work ◦ an understanding of the loading in cells could aid in developing struc- tures to grow cells or organization of cells more efficiently ◦ can help us to understand macrostructured behavior better ◦ can help us to build machines/sensors similar to cells ◦ can help us understand the biology of the cell ◦ cell growth is affected by stress and mechanical properties of the substrate the cells are in ◦ understanding mechan- ics is important for knowing how cells move and for figuring out how to change cell motion ◦ when building/engineering tissues, the tissue must have the necessary me- chanical properties ◦ understand how cells is affected by and affects its environment ◦ understand how mechanical factors alter cell behavior (gene expression) -

Bruises- Wounds

Henry Shih OD, MD Medical Director Austin Emergency Center- Anderson Mill 13435 US Highway 183 North Suite 311 Austin, TX 78750 512-614-1200 BRUISES- http://austiner.com/ What are bruises? — Bruises happen when blood vessels under the skin break, but the skin isn’t cut. Blood leaks into the tissues under the skin. Bruises start off red in color, and then turn blue or purple. As they heal, bruises can turn green and yellow. Most bruises heal in 1 to 2 weeks, but some take longer. How are bruises treated? — A bruise will get better on its own. But to feel better and help your bruise heal, you can: o Put a cold gel pack, bag of ice, or bag of frozen vegetables on the injured area every 1 to 2 hours, for 15 minutes each time. Put a thin towel between the ice (or other cold object) and your skin. Use the ice (or other cold object) for at least 6 hours after your injury. Some people find it helpful to ice longer, even up to 2 days after their injury. o Raise the area, if possible – Raising the area above the level of your heart helps to reduce swelling. o Take medicine to reduce the pain and swelling – To treat pain, you can take Tylenol. To treat pain and swelling, you can take ibuprofen (sample brand names: Advil, Motrin). But people who have certain conditions or take certain medicines should not take ibuprofen. If you are unsure, ask your doctor or nurse if you can take ibuprofen. -

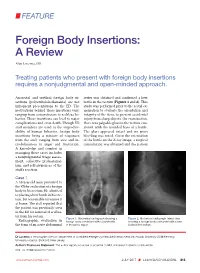

Foreign Body Insertions: a Review

FEATURE Foreign Body Insertions: A Review Alan Lucerna, DO Treating patients who present with foreign body insertions requires a nonjudgmental and open-minded approach. Anorectal and urethral foreign body in- series was obtained and confirmed a beer sertions (polyembolokoilamania) are not bottle in the rectum (Figures 1 and 2). This infrequent presentations to the ED. The study was performed prior to the rectal ex- motivations behind these insertions vary, amination to evaluate the orientation and ranging from autoeroticism to reckless be- integrity of the item, to prevent accidental havior. These insertions can lead to major injury from sharp objects. On examination, complications and even death. Though ED there was palpable glass in the rectum con- staff members are used to the unpredict- sistent with the rounded base of a bottle. ability of human behavior, foreign body The glass appeared intact and no gross insertions bring a mixture of responses bleeding was noted. Given the orientation from the staff, ranging from awe and in- of the bottle on the X-ray image, a surgical credulousness to anger and frustration. consultation was obtained and the patient A knowledge and comfort in managing these cases includes a nonjudgmental triage assess- ment, collective professional- ism, and self-awareness of the staff’s reaction. Case 1 A 58-year-old man presented to the ED for evaluation of a foreign body in his rectum. He admitted to placing a beer bottle in his rec- tum, but was unable to remove it at home. The staff reported that the patient was previously seen in the ED for removal of a vibra- tor from his rectum. -

Foreign Rectal Body – Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

REVIEW 61 Foreign rectal body – Systematic review and meta-analysis M. Ploner1, A. Gardetto2, F. Ploner3, M. Scharl4, S. Shoap5, H. C. Bäcker5 (1) Department of Anesthesiology and Intensiver Care, Cantonal Spital Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland ; (2) Department of Plastic Surgery, Hospital Sterzing, Sterzing, South Tirol, Italy ; (3) Department of Anesthesiology and Emergency Medicine, Hospital Sterzing, South Tirol, Italy ; (4) Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospital Zurich, University of Zurich, Swetzerland ; (5) Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, USA. Abstract instrumentation (7). The most common complication is a rectal injury, which can result from a variety of agents and Background : Self-inserted foreign rectal bodies are an objects (8). Often, nonsurgical removal of foreign bodies infrequent occurrence, however they present a serious dilemma to the surgeon, due to the variety of objects, and the difficulty of has been described to be successful – in 11% to 65% – extraction. The purpose of this study is to give a comprehensive (9), however, in many situations, a surgical treatment review of the literature regarding the epidemiology, diagnostic may be essential. There have been a variety of algorithms tools and therapeutic approaches of foreign rectal body insertion. Methods : A comprehensive systematic literature review on introduced for the management of extraction, however, Pubmed/ Medline and Google for ‘foreign bodies’ was performed because of the diversity of foreign bodies, improvisation, on January 14th 2018. A meta-analysis was carried out to evaluate as well creativity of the treating emergency physician the epidemiology, diagnostics and therapeutic techniques. 1,551 abstracts were identified, of which 54 articles were included. -

NEISS Coding Manual January 2018

NNEEIISSSS CCooddiinngg MMaannuuaall JJaannuuaarryy 22001188 NEISS – National Electronic Injury Surveillance System January 2018 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 General Instructions ................................................................................................................................... 1 General NEISS Reporting Rule .................................................................................................................. 1 Do Report .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Definitions .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Do Not Report ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Specific Coding Instructions ..................................................................................................................... 4 Medical Information Codes ........................................................................................................................ 4 Date of Treatment ..................................................................................................................................... 4 (8 spaces).................................................................................................................................................