Museology - Cultural Management”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliament Special Edition

October 2016 22nd Issue Special Edition Our Continent Africa is a periodical on the current 150 Years of Egypt’s Parliament political, economic, and cultural developments in Africa issued by In this issue ................................................... 1 Foreign Information Sector, State Information Service. Editorial by H. E. Ambassador Salah A. Elsadek, Chair- man of State Information Service .................... 2-3 Chairman Salah A. Elsadek Constitutional and Parliamentary Life in Egypt By Mohamed Anwar and Sherine Maher Editor-in-Chief Abd El-Moaty Abouzed History of Egyptian Constitutions .................. 4 Parliamentary Speakers since Inception till Deputy Editor-in-Chief Fatima El-Zahraa Mohamed Ali Current .......................................................... 11 Speaker of the House of Representatives Managing Editor Mohamed Ghreeb (Documentary Profile) ................................... 15 Pan-African Parliament By Mohamed Anwar Deputy Managing Editor Mohamed Anwar and Shaima Atwa Pan-African Parliament (PAP) Supporting As- Translation & Editing Nashwa Abdel Hamid pirations and Ambitions of African Nations 18 Layout Profile of Former Presidents of Pan-African Gamal Mahmoud Ali Parliament ...................................................... 27 Current PAP President Roger Nkodo Dang, a We make every effort to keep our Closer Look .................................................... 31 pages current and informative. Please let us know of any Women in Egyptian and African Parliaments, comments and suggestions you an endless march of accomplishments .......... 32 have for improving our magazine. [email protected] Editorial This special issue of “Our Continent Africa” Magazine coincides with Egypt’s celebrations marking the inception of parliamentary life 150 years ago (1688-2016) including numerous func- tions atop of which come the convening of ses- sions of both the Pan-African Parliament and the Arab Parliament in the infamous city of Sharm el-Sheikh. -

The Interface of Religious and Political Conflict in Egyptian Theatre

The Interface of Religious and Political Conflict in Egyptian Theatre Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amany Youssef Seleem, Stage Directing Diploma Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Advisor Nena Couch Beth Kattelman Copyright by Amany Seleem 2013 Abstract Using religion to achieve political power is a thematic subject used by a number of Egyptian playwrights. This dissertation documents and analyzes eleven plays by five prominent Egyptian playwrights: Tawfiq Al-Hakim (1898- 1987), Ali Ahmed Bakathir (1910- 1969), Samir Sarhan (1938- 2006), Mohamed Abul Ela Al-Salamouni (1941- ), and Mohamed Salmawi (1945- ). Through their plays they call attention to the dangers of blind obedience. The primary methodological approach will be a close literary analysis grounded in historical considerations underscored by a chronology of Egyptian leadership. Thus the interface of religious conflict and politics is linked to the four heads of government under which the playwrights wrote their works: the eras of King Farouk I (1920-1965), President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970), President Anwar Sadat (1918-1981), and President Hosni Mubarak (1928- ). While this study ends with Mubarak’s regime, it briefly considers the way in which such conflict ended in the recent reunion between religion and politics with the election of Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, as president following the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. This research also investigates how these scripts were written— particularly in terms of their adaptation from existing canonical work or historical events and the use of metaphor—and how they were staged. -

The Egyptian Museum Newsletter

L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ L@ THE EGYPTIAN MUSEUM NEWSLETTER In this issue A Word ISSUE NUMBER TWO MAY-AUGUST 2008 from the Director A Word from the Director Museums are now built around tian cultural heritage and history. seum and the Predynastic Depart‐ Between the educational programmes with a Children participate in workshops ment of the SCA and incorporated social role to teach members of to explore what they have seen in training sessions and exchange Past and the the society regardless of class or the Museum in a variety of media, between both museums, as well Present ethnicity. making them gain further knowl‐ as workshops. The museum edu‐ After my first publication edge through practical activities, cation Department arranged about children’s museums 1993, I which helps reinforce their mu‐ hands‐on training sessions for stu‐ Exhibitions made it my goal to make muse‐ seum experiences. dents in their fourth and fifth ums around the country aware of In collaboration with the years in the Faculty of Arts from the importance of museum educa‐ Ministry of Social Cooperation for Helwan University and Cairo Uni‐ tion, especially for today’s chil‐ the Care of Street Children, the versity. During these sessions, stu‐ Egyptian dren, who are tomorrow’s leaders. museum education department dents were given background top‐ Museum The Museum Education accompanies a group of street chil‐ ics on archaeology and history Basement Department at the Egyptian Mu‐ dren every week on a visit to the such as myths, writing, children, seum has successfully carried out museum that culminates with a educational games, jewellery and several workshops under the su‐ workshop. -

40 Jahre Städtepartnerschaft Stuttgart – Cairo

40 Jahre Städtepartnerschaft Stuttgart – Cairo Twinned for 40 years Kontakt Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart Referat Verwaltungskoordination, Kommunikation und Internationales Abteilung Außenbeziehungen (L/OB-Int) Rathaus, Marktplatz 1 70173 Stuttgart Telefon 0711 216-60734 Fax 0711 216-60744 E-Mail: [email protected] Herausgeberin: Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart, Abteilung Außenbeziehungen; Text: Nadia vom Scheidt, Dr. Frédéric Stephan; Theater Lokstoff (Seite 10), Jörg Armbruster (Seiten 12 bis 13), Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Deutsch-Ägyptisches Jahr der Wissenschaft und Forschung (Seiten 15 bis 16); Fotos: Nadia vom Scheidt (Seiten 2, 9, 15, 20, 24, 25), Stadt Stuttgart (Seite 4), Sven Matis (Seite 7), Raimond Stetter (Seite 10), Deutsche Botschaft Kairo (Seite 11), Robert Hammel (Seite 17), Michael Eisele (Seite 21) Oktober 2019 40 Jahre Städtepartnerschaft Kairo Inhalt Vorwort Oberbürgermeister Fritz Kuhn . 3 Stuttgart und Kairo – 40 Jahre Partnerschaft . 5 Kunst und Kultur über Grenzen hinweg . 8 Fotografie und Film . 8 Literatur . 9 Musik . 9 Mit Bildung und Sport Horizonte erweitern . 11 Schulaustausch . 11 Jugendprojekte . 11 Jugendmigrationsrat 2013 bis 2017 . 12 Sportbegegnungen . 13 Theaterprojekt „Revolutionskinder” . 13 Jörg Armbruster: Rückkehr aus Kairo . 14 Wissenstransfer fördert nachhaltige Entwicklung in Stadt, Land und Gesellschaft . 16 Gemeinsames Masterprogramm IUSD für nachhaltige Urbanisierung: Interview mit Prof. Dr. Astrid Ley, Universität Stuttgart . 18 SEKEM-Initiative, Freunde, Hochschule, Stiftung . 20 Sichtbarkeit der Partnerschaft . .21 Veranstaltungen im Jubiläumsjahr 2019 . .22 Impressionen . .24 Kontakte bei der Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart . .26 1 40 Jahre Städtepartnerschaft Kairo Der Jubiläums-Partnerschaftstisch beim Empfang der Deutschen Botschaft Kairo zum Tag der Deutschen Einheit 2019 2 40 Jahre Städtepartnerschaft Kairo Liebe Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, 1979 war ein weltpolitisch unruhiges und turbulentes Jahr. -

Images of the Rekhyt from Ancient Egypt

AE 38 cover.qxd 6/9/06 1:40 pm Page 1 AEPrelim36.qxd 13/02/1950 19:25 Page 2 AEPrelim38.qxd 13/02/1950 19:25 Page 3 CONTENTS features ANCIENT EGYPT www.ancientegyptmagazine.com October/November 2006 From our Egypt Correspondent VOLUME 7, NO 2: ISSUE NO. 38 9 Ayman Wahby Taher with the latest news from Egypt and details of a new museum at Saqqara. EDITOR: Robert B. Partridge, 6 Branden Drive Knutsford, Cheshire, WA16 8EJ, UK Friends of Nekhen News Tel. 01565 754450 Renée Friedman looks at the presence of Nubians Email [email protected] 19 in the city at Hierakonpolis, and their lives there, as revealed in the finds from their tombs. ASSISTANT EDITOR: Peter Phillips The New Tomb CONSULTANT EDITOR: Professor Rosalie David, OBE in the Valley of the Kings EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS: 26 The fourth update on the recent discovery and the final clearance of the small chamber. Victor Blunden, Peter Robinson, Hilary Wilson EGYPT CORRESPONDENT ANOTHER new tomb in the Valley Ayman Wahby Taher of the Kings? 31 Nicholas Reeves reveals the latest news on the PUBLISHED BY: possibility of another tomb in the Royal Valley. Empire Publications, 1 Newton Street, Manchester, M1 1HW, UK Royal Mummies on view in the Tel: 0161 872 3319 Egyptian Museum Fax: 0161 872 4721 35 A brief report on the opening of the second mummy room in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. ADVERTISEMENT MANAGER: Michael Massey Tel. 0161 928 2997 The Ancient Stones Speak Pam Scott, in the first of three major articles, gives a SUBSCRIPTIONS: 36 practical guide to enable AE readers to read and understand the ancient texts written on temple and Mike Hubbard tomb walls, statues and stelae. -

Middle East Studies

Middle East Studies New & Forthcoming Books Fall 2017 Letter from the Director It gives me great pleasure to present our new and forthcoming scholarly and general titles in Middle East Studies. Bringing rich ethnographic and field-based research to the AUC Press list are Gender Justice and Legal Reform in Egypt, which examines the interplay between legal reform and gender norms and practices in Egypt, and Gypsies in Contemporary Egypt, a study of Gypsies in modern-day Cairo and Alexandria. Economist Khalid Ikram’s A Political Economy of Reforms in Egypt (forthcoming) provides a fascinating and richly informed analysis of Egypt’s economic development since 1952. Ethiopia: The Living Churches of an Ancient Kingdom, by Mary Anne Fitzgerald with Philip Marsden, contains stunning color photographs of some of the world’s most extraordinary churches, including many never before seen in print. In his beautifully illustrated Orientalist Lives (forthcoming), James Parry asks what brought painters and photographers in the nineteenth century to Arab lands and looks at how they traveled, lived, worked, and fared. And in our History and Biography section, Marcus Simaika, by Samir Simaika and Nevine Henein, recounts the life and times of the extraordinary founder of the Coptic Museum, while lives in exile and dramatic histories are movingly narrated in Neslishah: The Last Ottoman Princess and Farewell Shiraz. Dr. Nigel Fletcher-Jones For Authors We welcome proposals for scholarly monographs and general books concerning the Middle East and North African regions on a broad variety of topics including, but not limited to, Egyptology, eastern Mediterranean archaeology, art history, medieval and modern history, ethnography, environmental studies, migration, urban studies, gender, art and architectural history, religion, Middle-Eastern politics, political economy, and Arabic language learning. -

Kansas City, Missouri Abstract Booklet Layout and Design by Kathleen Scott Printed in San Antonio on March 20, 2017

The 68th Annual Meeting of the American Research Center in Egypt April 21-23, 2017 Intercontinental at the Plaza Hotel Kansas City, Missouri Abstract Booklet layout and design by Kathleen Scott Printed in San Antonio on March 20, 2017 All inquiries to: ARCE US Office 8700 Crownhill Blvd., Suite 507 San Antonio, TX 78209 Telephone: 210 821 7000; Fax: 210 821 7007 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.arce.org ARCE Cairo Office 2 Midan Simon Bolivar Garden City, Cairo, Egypt Telephone: 20 2 2794 8239; Fax: 20 2 2795 3052 E-mail: [email protected] Photo Credits Cover: Head of Sen-useret III, Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty, ca. 1874-1855 B.C.E. Yellow quartzite, 17 3/4 x 13 1/2 x 17 inches. The Nelson- Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 62-11. Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo opposite: Relief of Mentu-em-hat and Anubis, Egyptian (Thebes), Late Period, late 25th to early 26th Dynasty, 665-650 B.C.E. Limestone with paint. 20 5/16 x 15 13/16 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 48-28/2. Photo spread pages 10-11: Wall painting inside TT 286, tomb of Niay. Taken dur- ing conservation work by ARCE in November 2016. Photo by Kathleen Scott. Abstracts title page: Statue of Metjetji, Egyptian (Sakkara), 2371-2350 B.C.E. Wood and gesso with paint, copper, alabaster, and obsidian, 31 5/8 x 6 3/8 x 15 5/16 inches. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners. a Copy Can Be Downlo

Shaalan, Khaled (2014) The political agency of Egypt’s upper middle class : neoliberalism, social status reproduction and the state. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20382 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. The Political Agency of Egypt’s Upper Middle Class: Neoliberalism, Social Status Reproduction and the State Khaled Shaalan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2014 Department of Politics and International Studies SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Middle East Studies New and Forthcoming Books 2019

Middle East Studies New and Forthcoming Books 2019 For Authors We welcome proposals for scholarly monographs and general books concerning the Middle East and North Africa regions on a broad variety of topics including, but not limited to, Egyptology, eastern Mediterranean archaeology, art history, medieval and modern history, ethnography, environmental studies, migration, urban studies, gender, art and architectural history, religion, politics, political economy, and Arabic language learning. Nadia Naqib Senior Commissioning Editor (Cairo) [email protected] Modern and medieval history Biography and autobiography Political science Architecture Arabic language learning Anne Routon Senior Acquisitions Editor (New York) [email protected] Anthropology Sociology Art history and cultural studies (including film, theater, and music) Nigel Fletcher-Jones Director [email protected] Egyptology Archaeology of the eastern Mediterranean Ancient history 2 ANTHROPOLOGY & SOCIOLOGY ANTHROPOLOGY & SOCIOLOGY Gypsies in Contemporary Egypt Manhood Is Not Easy On the Peripheries of Society Egyptian Masculinities through the Life of Musician Sayyid Henkish Alexandra Parrs Karin van Nieuwkerk Little is known about Egypt’s Gypsies, called In this in-depth ethnography, Karin van Nieu- Dom by scholars, but variously referred to wkerk takes the autobiographical narrative of by Egyptians as Ghagar, Nawar, Halebi, or Sayyid Henkish, a musician from a long family Hanagra. In this book, sociologist Alexan- tradition of wedding performers in Cairo, as a dra Parrs draws on two years of fieldwork to lens through which to explore changing notions explore how Dom identities are constructed, of masculinity in an Egyptian community over negotiated, and contested in the Egyptian the course of a lifetime. Situating his account national context. -

With the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and Its Effect on Civil Society and Human Rights

Soc (2014) 51:68–86 DOI 10.1007/s12115-013-9740-3 GLOBAL SOCIETY US “Partnership” with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and its Effect on Civil Society and Human Rights Anne R. Pierce Published online: 18 December 2013 # The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Looking at Egypt before, during and after the Arab With the world reeling from the fascist assault, and facing the Spring, this paper examines the intersection of Christian Copts, new threat of Soviet expansionism, America asserted influ- the Muslim Brotherhood, the Egyptian army, moderate Muslims ence as never before. While forming alliances and economic and secular groups. In turn, it examines the Obama administra- and strategic partnerships throughout the world, the United tion’s policies toward Egypt. It discloses the surprising finding States also actively promoted democratic principles and that the only consistent aspect of the administration’s policy sought to expand the number of representative democracies. toward Egypt has been outreach to and engagement with the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Reagan all insisted that Muslim Brotherhood. At no time before or after the our principles were what made our power important, and Brotherhood’s ascent to prominence in Egyptian politics and espoused those principles in their speeches and documents. society did the administration make support of the Brotherhood There were times when the United States sullied its own cause conditional. At no time did it use US leverage - given the massive and credibility by making its enemy’s enemy a friend. But, the amount of financial and military aid Egypt was depending on, overriding goal during the postwar years was the expansion of and given the new Egyptian government’s desire for prestige in the realm of political and economic freedom. -

Press Clippings Aggregate for Dr. Angelique Corthals As Consultant (Unrelated to Published Scienti;Ic Articles) 2009-February 20

Millsaps College Department of Sociology and Anthropology World Dispatch We’re building a bigger, better alumni community. E-mail your updates to Spring [email protected]. Include your name, graduation year and everything what 2009 you’ve been up to and you’ll be included in the next edition of the newsletter. Become a part of the alumni network (www.millsapssoan.ning.com) and connect directly In this issue: with your former classmates. Chocolate Moreton Lecture Moreton series brings Series in the Sci- mummies to life at Millsaps expert sweet- ences updates Early February held the last In her lecture, Corthals ex- ens history installment of Millsaps College’s plained how the discovery of Recent Millsaps Moreton Lecture Series in the Egyptian mummies has helped Sciences, Dr. Angélique Cor- forensic anthropologists, archae- grad wins Ful- thals of State University of New ologists, and Egyptologists dis- bright, spends York at Stony Brook presented cover previously unknown influ- time in Albania her lecture entitled, “Forensic ences such as disease, landscape, Anthropology: Gone, But Not and climate change on ancient Departed.” She focused on her Egyptian culture. Contributed photo Millsaps profes- involvement in an ongoing proj- Dr. Angélique Corthals is a fo- Dr. W. Jeffrey Hurst ect in which she excavated and rensic anthropologist, using his- The next installment sor to present at investigated Hatshepsut and torical, medical, anthropological, in the acclaimed More- SfAA conference other royal mummies in Egypt. forensic and genetic approaches ton Lecture Series at Mill- The project was featured both to reveal information about an- saps College, scheduled on the Discovery Channel and in cient biological remains. -

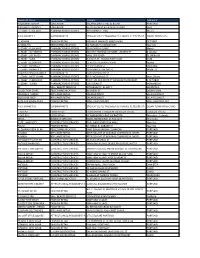

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM BUTCHERY EDUCATION SALAH ELDIN ST AND EL BAZAR PORTSAID BRILLIANCE SCHOOLS EDUCATION KILLO 26 CAIRO ALEX DESERT ROAD GIZA EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi ALFA MARKET 1 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST DOWN TOWN BLD., EL ADHAM FASHION RETAIL MEHWAR MARKAZY ABAZIA MALL OCTOBER ELHANA TEL TELECOMMUNICATION 12 HASSAN EL MAMOUN ST. Nasr city EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi EL EZABY - OCTOBER U PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 283 HAY 7 BEHIND OCTOBER UNIVERCITY 6 October EL EZABY - SKY PLAZA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES MALL SKY PLAZA EL SHEROUK EL EZABY - SUEZ PHARMACY/DRUG STORES ELGALAA ST, ASWAN INSTITUION SUEZ EL EZABY - ELDARAISA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 11 KILO15 ALEX-MATROUH Agamy EL EZABY- SHOBRA 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 113 SHOUBRA ST. SHOUBRA EL EZABY- ZAMALEK 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 6A ELMALEK ELAFDAL ST. ZAMALEK KHAYRAT ZAMAN MARKET SUPERMARKETS HATEM ROUSHDY ST EL EZABY - MEET GHAM PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 37 ELMOQAWQS ST Meet Ghamr EL EZABY - ELMEHWAR PHARMACY/DRUG STORES PIECE 101,3RD DISTRICT,MEHWAR ELMARKAZY 6 OCTOBER EL EZABY - SUDAN PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 166 SUDAN ST. MOHANDSIN EV SPA / BEAUTY SERVICES 278 HEGAZ ST. EL HAY 7 HELIOPOLIS COLLECTION STARS TELECOMMUNICATION 39 SHERIF ST. DOWNTOWN SAMSUNG ASWAN APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST GOLD LINE SHOP APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST ELITE FOR SHOES ASWA FASHION RETAIL MALL ASWAN PLAZA MALL ASWAN PLAZA ALFA MARKET S3 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST- DOWN TOWN-NEW CAIRO ELSHEIBY FOOD RETAIL 124 MASR WEL SUDAN ST.HADDayek El koba Haddayek El koba ELSHEIBY 2 FOOD RETAIL 67 SAKR KORICH BLD.SHERATTON Sheratton - Helipolis SIR KIL BUSINESS SERVICES 328 EL NARGES BLD.