H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 991 27 October 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif

“Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani To cite this version: Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani. “Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif.. Comparativ, Leipzig University, 2019, 29 (3), pp.41-64. hal-02954571 HAL Id: hal-02954571 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02954571 Submitted on 1 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo, 1890-1914. Debates about abolition of slavery have essentially focused on two interrelated questions: 1) whether nineteenth and early twentieth century abolitions were a major breakthrough compared to previous centuries (or even millennia) in the history of humankind during which bondage had been the dominant form of labour and human condition. 2) whether they express an action specific to western bourgeoisie and liberal civilization. It is true that the number of abolitionist acts and the people concerned throughout the extended nineteenth century (1780- 1914) had no equivalent in history: 30 million Russian peasants, half a million slaves in Saint- Domingue in 1790, four million slaves in the US in 1860, another million in the Caribbean (at the moment of the abolition of 1832-40), a further million in Brazil in 1885 and 250,000 in the Spanish colonies were freed during this period. -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

Independence and Trade: the Speci C E Ects of French Colonialism

Independence and trade: the specic eects of French colonialism Emmanuelle Lavallée¤ Julie Lochardy June 2012z Very preliminary. Please do note cite. Abstract Empirical evidence suggests that colonial rule and subsequent indepen- dence inuence past and current trade of former colonies. Independence ef- fects could dier substantially across former empires if they are related to the end of dierent preferential trade arrangements. Thanks to an original dataset including new data on pre-independence bilateral trade, this paper explores the impact of independence on former colonies' trade (imports and exports) for dierent empires on the period 1948-2007. We show that independence reduces trade (imports and exports) with the former metropole and that this eect is mainly driven by former French colonies. We also nd that, after independence, trade of all former colonies increase with third countries. A close inspection of the eects over time highlights that independence eects are gradual but tend to be more rapid and more intense in the case of exports. These results oer indirect evidence for the long-lasting inuence of colonial trade policies. Author Keywords: Trade; Decolonization; French Empire. JEL classication codes: F10; F54. ¤Université Paris-Dauphine, LEDa, UMR DIAL. Email: [email protected]. yErudite, University of Paris-Est Créteil. Email: [email protected]. zWe would like to thank participants at the IRD-DIAL Seminar and participants at the Con- ference on International Economics (CIE) 2012 for useful comments and suggestions. 1 1 Introduction Several studies highlight the consequences of colonial rule on bilateral trade. Mitchener and Wei- denmier (2008) assess the contemporaneous eects of empire on trade over the period 1870-1913. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

French Equatorial Africa

chapter 6 French Equatorial Africa 1 Introduction As in Britain, the imperialist wind blew through French politics and society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This renewed interest in overseas territories originated in a national trauma: the loss of most of the Alsace-Lorraine region to Germany in 1871. This event, a keenly felt humilia- tion, would determine French foreign policy until after World War i. French foreign and, by extension, colonial policy was directed at restoring its status among the other European powers: ‘France had to reforge her prestige in the community of European nations. This, according to Jules Ferry, would have to be done, not on the Rhine, but in Africa.’1 France mitigated its revanchist at- titude to Germany over time as it adjusted its national polities. Weighing the pros and cons of its colonial venture in Africa, France decided on an autono- mous colonial policy. Subordination, centralization, executive supremacy, uniformity and formality characterized French rule of its African territories. However, French criticism of informal empire, the system of rule used by Brit- ain and, to a lesser extent, Germany,2 diminished in the 1890s when France realized that direct rule of the overseas territories was impossible and that it necessarily had to deploy trading companies active on the ground. Despite its preference to acquire African territory by way of occupation, French control over Equatorial Africa originated in the establishment of pro- tectorates by concluding treaties with native rulers in the 1880s and 1890s.3 Once the French and African contracting parties had signed the treaty text, French law, administration and institutions were imported into the protector- ate. -

African Policemen in French Equatorial Africa, 1910S - 1930S

Between Colonizer and Colonized: African Policemen in French Equatorial Africa, 1910s - 1930s Hannah Levine Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Meredith McKittrick Honors Program Chairs: Professors Tommaso Astarita and Alison Games May 12, 2021 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Economics by Gunpoint 19 Chapter Two: Police, State, and Rebellion 44 Chapter Three: The Intermediary’s Quandary 67 Conclusion 87 Glossary 94 Appendix A: Photos of a Milicien and Two Tirailleurs 96 Appendix B: A.E.F.’s Civilian Administrative Structure 97 Bibliography 98 3 Acknowledgements Since pretty much everyone in my life—family, friends, housemates—had practically no choice but to be involved somehow in the writing of this thesis, I fortunately have a lot of people to feel grateful for at the completion of this work. Thank you all for putting up with me these last few months! All the same, there are a couple special people whom I need to recognize. First, I’d like to thank you, Professor Games, for your endless compassion and support as we navigated these challenging and isolating semesters online. You made this year worth it! A big thank you as well to my advisor, Professor McKittrick, for the wealth of knowledge that you shared with me. And of course, thank you to the other “Africanists” and all of my classmates in the thesis seminar. You all made this experience meaningful, collaborative, and fun, even on Zoom. I’d also like to thank two friends from home, Ana-Maria and Daphne, for being willing to go very much out of your way to get me the sources that I needed, even if the pandemic foiled some of our plans. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Reconstructing Empire in British and French Africa

Reconstructing Empire in British and French Africa Frederick Cooper Downloaded from It was indeed empire that European leaders at the end of World War II needed to reconstruct. They had come very close to losing a struggle with another form of empire, the Nazi Reich, and in South East Asia they had lost valued territories to a country that had dared to play the empire-game with them— Japan. At the same time, both British and French leaders felt, with some http://past.oxfordjournals.org/ reason, that they had been saved by their empires: by the resources in men and material contributed by the dominions and colonies of Great Britain and by the symbolic importance of French Equatorial Africa’s refusal to follow Vichy, followed by the contributions of North African territories and diverse African people to the reconquest of European France from the Mediterranean. Both post-war governments acknowledged the dilemma they faced: their physical and moral weakness at war’s end meant they had to find new bases to relegitimate empire, and their economic weakness meant at Virginia Tech on July 14, 2016 they needed the production of empire all the more. Both were acutely con- scious that another war might make them dependent on empire yet again. Leaders of political movements in the colonies were aware of exactly these points too. This chapter is a sketch—an attempt to lay out a way of thinking about the post-war era, a reflection on research by myself and others on a period that is only beginning to be explored. -

Writing African History in France During the Colonial Era Sophie Dulucq

Writing African History in France during the Colonial Era Sophie Dulucq To cite this version: Sophie Dulucq. Writing African History in France during the Colonial Era. Thomas Spear. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, 2018, 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.313. halshs- 01939221 HAL Id: halshs-01939221 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01939221 Submitted on 29 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Writing African History in France during the Colonial Era Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History Writing African History in France during the Colonial Era Sophie Dulucq Subject: Colonial Conquest and Rule, Historiography and Methods , Intellectual History Online Publication Date: Oct 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.313 Summary and Keywords In the second half of the 19th century, French imperial expansion in the south of the Sahara led to the control of numerous African territories. The colonial rule France imposed on a diverse range of cultural groups and political entities brought with it the development of equally diverse inquiry and research methodologies. A new form of scholarship, africanisme, emerged as administrators, the military, and amateur historians alike began to gather ethnographic, linguistic, judicial, and historical information from the colonies. -

General Agreement on 2K? Tariffs and Trade T£%Ûz'%£ Original: English

ACTION GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 2K? TARIFFS AND TRADE T£%ÛZ'%£ ORIGINAL: ENGLISH CONTRACTING PARTIES The Territorial Application of the General Agreement A PROVISIONAL LIST of Territories to which the Agreement is applied : ADDENDUM Document GATT/CP/l08 contains a comprehensive list of territories to which it is presumed the agreement is being applied by the contracting parties. The first addendum thereto contains corrected entries for Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, Indonesia, Italy, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. Since that addendum was issued the governments of the countries named below have also replied requesting that the entries concerning them should read as indicated. It will bo appreciated if other governments will notify the Secretariat of their approval of the relevant text - or submit alterations - in order that a revised list may be issued. PART A Territories in respect of which the application of the Agreement has been made effective AUSTRALIA (Customs Territory of Australia, that is the States of New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania and the Northern Territory). BELGIUM-LUXEMBOURG (Including districts of Eupen and Malmédy). BELGIAN CONGO RUANDA-URTJimi (Trust Territory). FRANCE (Including Corsica and Islands off the French Coast, the Soar and the principality of Monaco). ALGERIA (Northern Algeria, viz: Alger, Oran Constantine, and the Southern Territories, viz: Ain Sefra, Ghardaia, Touggourt, Saharan Oases). CAMEROONS (Trust Territory). FRENCH EQUATORIAL AFRICA (Territories of Gabon, Middle-Congo, Ubangi»-Shari, Chad.). FRENCH GUIANA (Department of Guiana, including territory of Inini and islands: St. Joseph, Ile Roya, Ile du Diablo). FRENCH INDIA (Pondicherry, Karikal, Yanaon, Mahb.) GATT/CP/l08/Add.2 Pago 2 FRANCE (Cont'd) FRENCH SETTLEMENTS IN OCEANIA (Consisting of Society; Islands, Leeward Islands, Marquozas Archipelago, Tuamotu Archipelago, Gambler Archipelago, Tubuaî Archipelago, Rapa and Clipporton Islands. -

Arnesen CV GWU Website June 2009

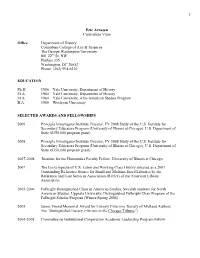

1 Eric Arnesen Curriculum Vitae Office Department of History Columbian College of Arts & Sciences The George Washington University 801 22nd St. NW Phillips 335 Washington, DC 20052 Phone: (202) 994-6230 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1986 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Department of History M.A. 1984 Yale University, Afro-American Studies Program B.A. 1980 Wesleyan University SELECTED AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2009 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2008 Principle Investigator/Institute Director, FY 2008 Study of the U.S. Institute for Secondary Educators Program (University of Illinois at Chicago), U.S. Department of State ($350,000 program grant) 2007-2008 Institute for the Humanities Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago 2007 The Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History selected as a 2007 Outstanding Reference Source for Small and Medium-Sized Libraries by the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) of the American Library Association. 2005-2006 Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Studies, Swedish Institute for North American Studies, Uppsala University, Distinguished Fulbright Chair Program of the Fulbright Scholar Program (Winter-Spring 2006) 2005 James Friend Memorial Award for Literary Criticism, Society of Midland Authors (for “distinguished literary criticism in the Chicago Tribune”) 2004-2005 Committee on Institutional -

Lessons from the History of the Congo Free State

BLOCHER &G ULATI IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 2/16/2020 7:11 PM Duke Law Journal VOLUME 69 MARCH 2020 NUMBER 6 TRANSFERABLE SOVEREIGNTY: LESSONS FROM THE HISTORY OF THE CONGO FREE STATE JOSEPH BLOCHER & MITU GULATI† ABSTRACT In November 1908, the international community tried to buy its way out of the century’s first recognized humanitarian crisis: King Leopold II’s exploitation and abuse of the Congo Free State. And although the oppression of Leopold’s reign is by now well recognized, little attention has been paid to the mechanism that ended it—a purchased transfer of sovereign control. Scholars have explored Leopold’s exploitative acquisition and ownership of the Congo and their implications for international law and practice. But it was also an economic transaction that brought the abuse to an end. The forced sale of the Congo Free State is our starting point for asking whether there is, or should be, an exception to the absolutist conception of territorial integrity that dominates traditional international law. In particular, we ask whether oppressed regions should have a right to exit—albeit perhaps at a price—before the relationship between the sovereign and the region deteriorates to the level of genocide. Copyright © 2020 Joseph Blocher & Mitu Gulati. † Faculty, Duke Law School. For helpful comments and criticism, we thank Tony Anghie, Stuart Benjamin, Jamie Boyle, Curt Bradley, George Christie, Walter Dellinger, Deborah DeMott, Laurence Helfer, Tim Lovelace, Ralf Michaels, Darrell Miller, Shitong Qiao, Steve Sachs, Alex Tsesis, and Michael Wolfe. Rina Plotkin provided invaluable research and linguistic support, Jennifer Behrens helped us track down innumerable difficult sources, and the editors of the Duke Law Journal delivered exemplary edits and suggestions.