(6-Month) (DG).Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Sky Area Sustainable Watershed Stewardship Plan

Big Sky Area Sustainable Watershed Stewardship Plan January 26, 2018 BIG SKY AREA SUSTAINABLE WATERSHED STEWARDSHIP PLAN Prepared by Jeff Dunn, Watershed Hydrologist Troy Benn, Water Resources Engineer Zac Collins, GIS Analyst And Karen Filipovich, Facilitator and Analyst Gary Ingman, Water Resources Scientist, Headwaters Hydrology Prepared for And Big Sky Sustainable Water Solutions Forum Big Sky, MT January 26, 2018 PO Box 160513 Big Sky, MT 59716 Over 2016-2017, the Gallatin River Task Force hosted a collaborative stakeholder driven effort to develop the Big Sky Area Sustainable Watershed Stewardship Plan. The Gallatin River Task Force (Task Force) is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Big Sky, with a focus on protecting and improving the health of the Upper Gallatin River and its tributaries. I would like to take this opportunity to thank the many entities and individuals involved in this effort. The main funders of plan development included the Big Sky Resort Area Tax District, and Gallatin and Madison Counties. Initial seed funding was provided by the Big Sky Water and Sewer District, Lone Mountain Land Company, and the Yellowstone Club. Thank you to the stakeholders and their representative organizations that contributed time, energy, and brain power to become educated in water issues in the Big Sky Community, roll up their sleeves and spend countless hours developing creative solutions to complex water issues. Thank you to the many member of the public who provided input by attending stakeholder and public meetings or taking our survey. Implementation of this plan will ensure that the ecological health of our treasured river systems are enhanced and protected as our community and region continue to grow in residential and visitor population. -

In Re Yellowstone Mountain Club: Equitable Subordination to Police Inequitable Conduct by Non-Insider Creditors Marina Montes

NORTH CAROLINA BANKING INSTITUTE Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 20 2010 In Re Yellowstone Mountain Club: Equitable Subordination to Police Inequitable Conduct by Non-Insider Creditors Marina Montes Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncbi Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Marina Montes, In Re Yellowstone Mountain Club: Equitable Subordination to Police Inequitable Conduct by Non-Insider Creditors, 14 N.C. Banking Inst. 495 (2010). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncbi/vol14/iss1/20 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Banking Institute by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In re Yellowstone Mountain Club: Equitable Subordination to Police Inequitable Conduct by Non-Insider Creditors I. INTRODUCTION [C]reditors who cause debtors' financial ruin should not be allowed to use the courts as their collection agents. The United States courts should not be enforcers for loan sharks. The Bankruptcy Code currently gives courts that power to equitably subordinate creditors who act improperly. But... it is applied inconsistently. Equitable subordination provides bankruptcy courts with the authority to place the first lien position of a self-enriching secured creditor in an inferior position to that of other secured or unsecured creditors.2 Historically, bankruptcy judges have been reluctant to use their power to subordinate3 a secured creditor's unjust claims in circumstances where they are not• • fiduciaries.5 For purposes of this Case Comment, a non-insider refers to any creditor that does not have fiduciary obligations. -

COVEY RISE Yellowstone Club

MOUNTAIN PARADISE A sportsman’s year-round playground set on about 14,000 acres, Montana’s Yellowstone Club redefines the club concept. STORY BY EVERETT POTTER PHOTOGRAPHY BY TERRY ALLEN AND THE YELLOWSTONE CLUB 46 COVEY RISE COVEY RISE 47 he drive from Bozeman, Montana, to the Yellowstone makes it larger than Deer Valley Resort in Utah or Sun Valley in Club takes about an hour, along a meandering road Idaho. The experience of gliding through powder with your best that follows the trophy trout waters of the Gallatin buddy, or carving the corduroy with your kids—accompanied TRiver. The river, the woodlands, and the snow-capped by just a couple dozen other skiers—and doing that all day long mountain peaks announce this as a sportsman’s dream landscape. and for days on end is the biggest selling point of the Yellow- Not long after the entrance to Big Sky Resort you reach the gates stone Club and why it’s been dubbed “Private Powder.” to the Yellowstone Club. The club’s 13,600 acres aren’t surround- Add access to the adjacent 6,000 acres of Big Sky and Moon- ed by fences, but they aren’t needed, given that the club’s security light Basin combined, and the deal sweetens considerably for force is staffed by former Secret Service agents. those who love snow and the outdoors. But as at so many West- Overkill? Not when you have a club whose members include ern resorts built on the concept of celebrating winter, there are some of the world’s wealthiest and highest-profile individuals. -

SW Construction Effective Permits by County (PDF)

Beaverhead NPDES ID Permittee Name Facility Name Location Address Effective Date MTR107358 SOUTHERN MT TELEPHONE CO INC WISDOM/JACKSON FIBER-TO-THE-PREMISE (FTTP) UPGRADE PROJECT 2018 IN AND AROUND THE TOWN OF JACKSON 6/27/18 MTR107551 WESTERN FEDERAL LANDS HIGHWAY DIVISION, FHW NORTH OF MOOSE CREEK NORTH MT DOT 569(3) MT 43 ON THE SOUTH AND MT 1 ON THE NORTH 10/17/18 MTR107665 Deere Creek Excavation, LLC STODDEN SLOUGH RESTORATION PROJECT 280 SILVER MAPLE LANE 1/11/19 MTR107964 JIM GILMAN EXCAVATING INC CLARK CANYON RES. - BARRETTS INTERSTATE 15, MILE POST 45.9 TO 54.5 7/10/19 MTR108259 SOUTHERN MT TELEPHONE CO INC SOUTHERN MONTANA TELEPHONE - 2020 JACKSON UPGRADE PROJECT 205 MAIN STREET 3/6/20 MTR108420 BARRETTS MINERALS INC BARRETS MINERALS REGAL MINE 15 MI EAST OF DILLON 6/19/20 MTR108783 SOUTHERN MT TELEPHONE CO INC SOUTHERN MONTANA TELEPHONE COMPANY - GRANT FTTP UPGRADE 2021 205 MAIN STREET 3/4/21 MTR108846 SCHELLINGER CONSTRUCTION CO WISDOM - WEST / TRAIL CREEK STRUCTURES MT 43 RP 7.5 TO RP 26.2 4/1/21 MTR108988 MUNGAS COMPANY INC 2021 DILLON - WATER SYSTEM IMPROVEMENTS IDAHO STREET 6/22/21 Big Horn NPDES ID Permittee Name Facility Name Location Address Effective Date MTR106659 ALTA VISTA OIL CORP SLAUGHTERVILLE-1H FROM DECKER NE ON HWY 314 2.8 MI. E ON OTTER/QUIET 1/1/18 MTR107081 ALTA VISTA OIL CORPORATION DOC HOLIDAY-1H FROM DECKER NE ON HWY 314 2.8 MI E ON OTTER/QUIETU 1/1/18 MTR107633 NAVAJO TRANSITIONAL ENERGY COMPANY LLC SPRING CREEK MINE WINDMILL DRIVE 12/13/18 MTR108475 MONTANA DEPT OF TRANSPORTATION PERITSA CREEK - 6 MILES -

The Yellowstone Club Big Sky, MONTANA BIG SKY 3.0

FEATURING The Yellowstone Club Big Sky, MONTANA BIG SKY 3.0 By Lee Roberts The community of Big Sky, Montana, once the ski-centric dream Fortunately, Byrne, the Yellowstone Club’s impresario, besides being From scholarships to improvements in the school lunch program, Byrne and its ability to stabilize the local economy. Specialty contracting of iconic newsman and Montana native Chet Huntley has a new a member, also has other ventures in the Gallatins sure to keep him describes the Yellowstone Club Community Foundation as integral to company Stoa Management’s Austin Rector says, “The kinetic energy of interpretation. Huntley’s plan to draw those seeking the respite of a near these places where he engages in perhaps his favorite pastime, the community’s growth and success. “[Big Sky is] the fastest growing Sam Byrne and his team is exactly what Southwest Montana’s economy mountain adventure has been quietly realized for decades. The new skiing. Though details remain private, a merger designed in part to school district in the state,” says Byrne. State of Montana numbers needs. Big Sky is attracting international interest and our firm is feeling relieve Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc. of its distressed assets, Byrne’s architect of Huntley’s plan, CrossHarbor Capital’s Sam Byrne, wants to confirm that Gallatin County has beaten the other 55 counties in growth the positive effects of this activity.” CrossHarbor and ski magnate Boyne Resorts have purchased two for several years. Big Sky School District Superintendent Jerry House raise the volume and increase the audience for this Montana story. -

Oct 2 5 1999

THE VIABILITY OF A PRIVATE FOUR-SEASON RESORT IN NORTHERN NEW ENGLAND by William D. Adams B.A., Political Science, 1987 Lehigh University & Shawn M. Hurley B.A., Architecture, 1994 Washington University Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 1999 © 1999 William D. Adams and Shawn M. Hurley. All rights reserved. The authors hereby grant to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: D rtmentof n uanng Signature of Author: "epartrneni%6f Urb aO ies n ing J , 1999 Certified by: Blake Eagle Chairman, Center for Real Estate Thesis Advisor Accepted by: William C. Wheaton FMASSACHUSETTS INSTITU Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development OF TECHINOLOGY OCT 2 5 1999 LIBRARI=.Q THE VIABILITY OF A PRIVATE FOUR-SEASON RESORT IN NORTHERN NEW ENGLAND by William D. Adams & Shawn M. Hurley Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on July 30, 1999 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development. at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ABSTRACT The avid New England skier is having increasing difficulty enjoying their sport. In the age of consolidation and rising costs, the New England ski industry is becoming overcrowded and less fun for the consumer. The ski industry throughout the country and particularly in New England has realized little growth over the past ten years. -

BIG SKY, MONTANA Shop/3Cstuffandthings

THURSDAY lonepeaklookout.com June 14, 2018 FREE Volume 1, Issue 28 BigBig Sky, Sky, LONELONE PEAKPEAK LOOKOUTLOOKOUT MontanaMontana The community housing That truck smell conversation is called to order Brand new newPierce fire engine arrives in Big Sky Big Sky starts to activate new action plan BY DAVID MADISON been here before. They’ve filled to be significant bumps in local [email protected] filing cabinets with successful rents, even compared to other plans for other alpine expensive ski towns. irst, there’s the destinations such as Aspen, “So it’s a little bit less remarkable cross Breckenridge, Mammoth Lakes affordable for rents in section of Big Sky and Whitefish. Big Sky than other resort Flocals who stepped up and Brian Guyer, with HRDC communities,” said Walker, bought into the notion that, and the Big Sky Community who explained how affordable “It takes a community to Housing Trust, said Sullivan “community housing” is build a community.” There and Walker, “Were really defined by 30 percent of are 21 names listed in the tasked with coming up with a income put toward rent or a acknowledgements section of homegrown solution for Big mortgage. the recently released “Big Sky S k y.” Next, Sullivan delved into Community Housing Action Like good friends pushing how Big Sky arrived at its Plan” and those folks (see list a pal to ski something they community housing problems. at lonepeaklookout.com) are wouldn’t otherwise consider— “Between 2012 and 2017, stand ins for the more than but will ultimately love—these you guys had phenomenal job 1,000 people who poured two unfolded a new trail map growth. -

A Man of Conviction | 1

A Man of Conviction | 1 A Man of Conviction By Kerry Pechter Wed, Apr 17, 2013 How did Matthew Hutcheson, once a poster boy for fiduciary rectitude, turn into the wanted-poster man for fiduciary misconduct? But his ill-fated deal for the Osprey Meadows golf course (pictured) in Idaho was just a subplot within a subplot of the 2008 real estate bust. Even as a federal jury in Boise, Idaho found him guilty Monday of wire fraud related to the misuse of million of dollars taken from the retirement plans he managed, Matthew Hutcheson claimed that he was innocent and was only trying to help the participants in the plans. Perhaps for that reason, there’s something about Hutcheson’s case that still feels unresolved—even though he now faces the possibility of spending several years in prison, probably in a minimum-security federal penitentiary. How and why did the earnest, fresh-faced man who had once been the poster boy for fiduciary rectitude, testifying on Capitol Hill, turn so quickly into the wanted-poster boy for fiduciary misconduct. How did he go from the guardian of retirement plan participants to the convicted exploiter of those participants? It’s possible that Hutcheson’s behavior didn’t actually change. His activities in Idaho are consistent with what some had noticed earlier as those of an ambitious self-promoter. His desire to do well seemed at least as strong as his desire to do good, and the former may have simply have had an opportunity to exceed the latter. Or maybe he was not able to see a clear line between the two. -

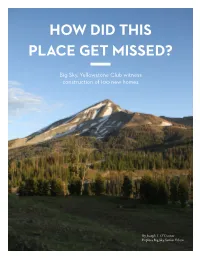

How Did This Place Get Missed?

HOW DID THIS PLACE GET MISSED? Big Sky, Yellowstone Club witness construction of 100 new homes By Joseph T. O’Connor Explore Big Sky Senior Editor BIG SKY – This is not Big Sky Country, where waist-tall branding them with a capital C. grass blows against an alpine backdrop and ranchers in chaps and Stetsons herd cattle. This is Big Sky, Montana, where As of this fall, Big Sky Resort, Moonlight Basin, the Club at media moguls, Hollywood superstars and dot-com investors Spanish Peaks and the Yellowstone Club now sit under one large own second and third homes in wealthy, private commu- umbrella stretching from Boston, Mass. to cover this unincorpo- nities. Ski resorts are their corrals and multi-million dollar rated town and its approximately 2,400 year-round residents. mansions their ranches. On Oct. 1, Boston-based CrossHarbor Capital Partners, LLC Tucked into the southwest corner of Montana, Big Sky is part and Boyne Resorts closed on the purchase of Moonlight of the elite corps of American ski towns that includes Aspen Basin, a 1,900-acre ski area adjacent to Big Sky Resort – which and Vail, Colo., and Jackson, Wyo. in terms of snowfall, ter- Boyne owns – with an additional 10,000 acres of developable rain and amenities. Just 11 miles from Yellowstone National land and a master plan for 400-plus residential units. The Park, it has three blue-ribbon fly fishing streams within purchase followed on the heels of the partnership’s July 19 casting distance. The nearby college town of Bozeman was acquisition of the assets in the previously bankrupt Club at ranked fifth in Outside Magazine’s Best Town’s list. -

12M Raised for Big Sky Community Center

April 26 - May 9 Volume 10 // Issue #9 Spring lands in Big Sky Growing pains: The West is booming BSSD’s New-trition Overcrowding on the Madison River $12M raised for Big Sky community center Wolves and the Nez Perce TABLE OF CONTENTS OPINION.....................................................................5 HEALTH.....................................................................31 OP NEWS....................................................................6 SPORTS.....................................................................29 LOCAL.........................................................................7 BUSINESS.................................................................41 MONTANA.................................................................15 DINING.....................................................................42 ENVIRONMENT.........................................................17 FUN...........................................................................43 OUTDOORS..............................................................20 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT........................................41 April 26 - May 9, 2019 Volume 10, Issue No. 9 Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana Growing pains: The West is booming PUBLISHER 8 Can Gallatin County sustain the waves of Americans abandoning major metropolitan markets for Eric Ladd | [email protected] quality of life the Intermountain West? EDITORIAL EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, VP MEDIA BSSD’s New-trition Joseph T. O’Connor | [email protected] 13 Lindsie -

The New Global Completion Centre

Bombardier Business Aircraft Magazine Issue 20 2013 THE NEW GLOBAL COMPLETION CENTRE NETJETS’ GLOBAL 6000 SIGNATURE SERIES AIRCRAFT KEITH URBAN’S SKY-HIGH GIG + SAIL THE WORLD + SKI YELLOWSTONE CLUB TRAVEL: MONTANA WELCOME TO THE CLUB Occupying a superlative slice of southwestern Montana, the Yellowstone Club aims to cater to its intrepid members’ every whim. BY NEAL McLENNAN anna cut through Warren Miller’s backyard?” grins my “ guide Steve, making a conspiratorial gesture at a glade of trees just below the sprawling stone-and-cedar moun- tainside home of the ski filmmaker. I’m halfway down theW hill at Montana’s Yellowstone Club and, from the looks of the largely untracked mid-afternoon snow, we appear to be the sole skiers on the mountain. Steve’s suggestion to trespass serves a 40-year-old’s need to feed the inner juvenile. So of course we do it. To be fair, it’s a harmless transgression. Miller, the Yellowstone Club’s honorary director of skiing, is more likely to invite trespassers like us into his home for tea than to shoo us off with a shotgun. Like the rest of the club’s approximately 400 members, he’s excessively content in the charms of this 13,600-acre private ski and golf retreat tucked into the Madison range of southwest Montana. A few turns later we’re at the main lodge, a 140,000-square-foot (13,006-square-meter) post-and-beam chalet on steroids. This ethos – big without the buffoonery – is the cornerstone of Yellowstone’s mystique. For years, whispers abounded of a private Montana ski club, home to a world-class golf course that was so sparingly played you could simply walk on whenever the mood struck. -

Application Review #1 Agenda 406.995.3234 June 7Th, 2021 | 5:30 Pm

Big Sky Resort Area District 11 Lone Peak Drive #204 PO Box 160661 Big Sky, MT 59716 www.Resorttax.org [email protected] Application Review #1 Agenda 406.995.3234 June 7th, 2021 | 5:30 pm I. Open Meeting -- 5:30 A. Public Comment B. Regular Agenda a. Intro & Chair Statement: Discussion b. FY22 Calendar: Action c. FY22 Reserves: Discussion d. Funds Available: Discussion e. Executive Recommendations: Discussion C. Application Review: Action a. 3-year Government Operations b. Projects over $100,000 c. Projects under $100,000 D. Public Comment BSRAD BOARD & STAFF: Kevin Germain, Chair | Sarah Blechta, Vice Chair | Steve Johnson, Secretary & Treasurer | | Ciara Wolfe, Director | Grace Young, Director | Daniel Bierschwale, Executive Director | Kristin Drain, Finance & Compliance Manager |Jenny Muscat, Operations Manager | Sara Huger, Administrative Assistant * All Board Meetings are recorded and live streamed. Please visit ResortTax.org for more information. Public Comment Overview (Public Comment received as of 06.04.21) Beehive Property Management, Troy Nedved & Liv Grubaugh, & Chris Torsleff shared general support for Big Sky Ski Education Foundation. Jessie Wiese shared a letter detailing the impact of traffic on Big Sky’s wildlife and support for the Center for Large Landscape Conservation’s Wildlife and Transportation Conflict Assessment project application. Patricia Doherty & Rene Kraus shared general support for the library. Liz Lodman, AIS Information Officer, Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks, shared support for Gallatin Invasive Species Alliance’s Education & Outreach project and their impact on Aquatic Invasive Species. Abigail King, on behalf of the Jack Creek Preserve Foundation’s Board of Directors, wrote in support of the Alliance’s Education and Outreach program.