INTRODUCTION Statement of the Problem Although News Media Has Been Part of Media Studies for Decades, It Has Recently Started To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

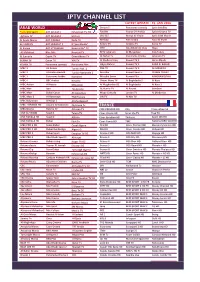

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

LES CHAÎNES TV by Dans Votre Offre Box Très Haut Débit Ou Box 4K De SFR

LES CHAÎNES TV BY Dans votre offre box Très Haut Débit ou box 4K de SFR TNT NATIONALE INFORMATION MUSIQUE EN LANGUE FRANÇAISE NOTRE SÉLÉCTION POUR VOUS TÉLÉ-ACHAT SPORT INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE MULTIPLEX SPORT & ÉCONOMIQUE EN VF CINÉMA ADULTE SÉRIES ET DIVERTISSEMENT DÉCOUVERTE & STYLE DE VIE RÉGIONALES ET LOCALES SERVICE JEUNESSE INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE CHAÎNES GÉNÉRALISTES NOUVELLE GÉNÉRATION MONDE 0 Mosaïque 34 SFR Sport 3 73 TV Breizh 1 TF1 35 SFR Sport 4K 74 TV5 Monde 2 France 2 36 SFR Sport 5 89 Canal info 3 France 3 37 BFM Sport 95 BFM TV 4 Canal+ en clair 38 BFM Paris 96 BFM Sport 5 France 5 39 Discovery Channel 97 BFM Business 6 M6 40 Discovery Science 98 BFM Paris 7 Arte 42 Discovery ID 99 CNews 8 C8 43 My Cuisine 100 LCI 9 W9 46 BFM Business 101 Franceinfo: 10 TMC 47 Euronews 102 LCP-AN 11 NT1 48 France 24 103 LCP- AN 24/24 12 NRJ12 49 i24 News 104 Public Senat 24/24 13 LCP-AN 50 13ème RUE 105 La chaîne météo 14 France 4 51 Syfy 110 SFR Sport 1 15 BFM TV 52 E! Entertainment 111 SFR Sport 2 16 CNews 53 Discovery ID 112 SFR Sport 3 17 CStar 55 My Cuisine 113 SFR Sport 4K 18 Gulli 56 MTV 114 SFR Sport 5 19 France Ô 57 MCM 115 beIN SPORTS 1 20 HD1 58 AB 1 116 beIN SPORTS 2 21 La chaîne L’Équipe 59 Série Club 117 beIN SPORTS 3 22 6ter 60 Game One 118 Canal+ Sport 23 Numéro 23 61 Game One +1 119 Equidia Live 24 RMC Découverte 62 Vivolta 120 Equidia Life 25 Chérie 25 63 J-One 121 OM TV 26 LCI 64 BET 122 OL TV 27 Franceinfo: 66 Netflix 123 Girondins TV 31 Altice Studio 70 Paris Première 124 Motorsport TV 32 SFR Sport 1 71 Téva 125 AB Moteurs 33 SFR Sport 2 72 RTL 9 126 Golf Channel 127 La chaîne L’Équipe 190 Luxe TV 264 TRACE TOCA 129 BFM Sport 191 Fashion TV 265 TRACE TROPICAL 130 Trace Sport Stars 192 Men’s Up 266 TRACE GOSPEL 139 Barker SFR Play VOD illim. -

Iptv Channel List Latest Update : 15

IPTV CHANNEL LIST LATEST UPDATE : 15. JAN 2016 ARAB WORLD Dream 2 Panorama comedy Syria Satellite *new Nile Sport ART AFLAM 1 Echourouk TV HD Fatafet France 24 Arabia Syrian Drama TV Aghapy TV ART AFLAM 2 Elsharq LBC SAT Rusiya Al-Yaum Syria 18th March Al Aoula Maroc ART CINEMA Kaifa TV Melody FOX arabia Nour El Sham AL HANEEN ART HEKAYAT 2 N*geo Abuda* Future TV Arabica TV Sama TV Al Karma ART H*ZAMANE Noorsat Sh* TV OTV Abu Dhabi AL Oula Heya Al Malakoot Blue Nile Noorsat TV MTV Lebanon Al Mayadeen Iraq Today Al Sumaria Coptic TV Orient News TV Al Nahar Tv Panorama Drama Lebanon TV BENNA TV Coran TV VIN TV Al Rasheed Iraq Kuwait TV 1 Hona Alquds YEMEN TV Panorama comedy Panorama Film Libya Alahrar Kuwait TV 2 SADA EL BALAD MBC 1 AL Arabia Tunisie Nat. 1 DW-TV Kuwait TV 3 AL MASRIYA MBC 2 Al Arabia Hadath Tunisie Nationale 2 Mazzika Kuwait Sport + YEMEN TODAY MBC 3 Euronews Arabia Hannibal Mazzika Zoom Kuwait Plus KAHERAWELNAS MBC 4 BBC Arabia Nessma Orient News TV Al Baghdadia 2 Al Kass MBC Action Al Resala Ettounisia Al Magharibia DZ Al Baghdadia Al Kass 2 MBC Max Iqra Tounessna AL Hurria TV Al Fourat SemSem MBC Masr Dubai Coran Al Janoubiya Moga Comedy Jordan TV Al Ekhbariya MBC Masr 2 Al Haramayn TNN Tunisia ON TV Al Nas TV MBC Bolywood Al Majd 3 Al Moutawasit MBC + DRAMA HD Assuna Annabaouia Zaytouna Tv FRANCE MBC Drama Rahma TV Al Insen TV CINE PREMIER HD City Trace urban hd OSN AL YAWM Saudi 1 Telvza TV Cine+ Classic HD Sci et Vie TV Trek TV OSN YAHALA HD Saudi 2 Attasia Cine+ Emotion HD Thalassa Sport 365 HD OSN YAHALA HD Dubai -

TV Channel Monitoring

TV Channel Monitoring The channels below are monitored in real- time, 24/7. United States 247 channels NATIONAL A&E Comedy Central Fuse ABC CW FX ABC Family Destination America GAC AHC Discovery Galavision (GALA) AMC Discovery Fit & Health Golf Channel Animal Planet Discovery ID GSN BBC America Disney Channel Hallmark Channel BET DIY HGTV Big Ten Network E! History Channel Biography Channel ESPN HLN Bloomberg News ESPN 2 HSN BRAVO ESPN Classic IFC Cartoon Network ESPN News ION CBS ESPN U Lifetime CBS Sports Food Network LOGO Cinemax East Fox 5 MLB CMT Fox Business MSG Network CNBC Fox News MSNBC CNBC World Fox Sports 1 MTV CNN Fox Sports 2 MTV2 My9 Science Channel Travel Channel National Geographic ShowTime East truTV NBA Spike TV TV1 NBC SyFy TV Guide NBC Sports (Versus) TBN TV Land NFL TBS Univision NHL TCM USA Nickelodeon Telemundo VH1 Nicktoons Tennis Channel VH1 Classic OLN The Cooking VICELAND Oprah Winfrey Net. Channel WE Ovation The Hub WGN America Oxygen Time Warner Cable WLIW QVC TLC YES REELZ TNT New York ABC (WABC) Fox (WNYW) Univision (WXTV) CBS (WCBS) MyNetworkTV (WWOR) CW (WPIX) NBC (WNBC) Los Angeles ABC (KABC) CW (KTLA) NBC (KNBC) CBS (KCBS) FOX (KTTV) Univision (KMEX) Baltimore ABC (WMAR-DT) Fox (WBFF-DT) NBC (WBAL-DT CBS (WJZ-DT) MyNetworkTV CW (WNUV-DT) (WUTB-DT) Chicago ABC (WLS-DT) Fox (WFLD-DT) Univision (WGBO- CBS (WBBM-DT) NBC (WMAQ-DT) DT) CW (WGN-DT) San Diego ABC (KGTV) FOX (KSWB) The CW (KFMB) CBS (KFMB) NBC (KNSD) Univision (KBNT) The United Kingdom 74 Channels 4Music Home Nick Toons 5 star Horror Channel -

|Fr|Hd| France ##### |Fr| Flix

##### |FR|HD| FRANCE ##### |FR| RTS UN HD |FR| CORONA VIRUS INFO |FR| RTS DEUX HD |FR| TF1 HD |FR| CSTAR HD |FR| FRANCE 2 HD |FR| LA CHAINE METEO HD |FR| FRANCE 3 HD |FR| MEZZO FR |FR| FRANCE 4 HD |FR| MUSEUM HD |FR| FRANCE 5 HD |FR| COMEDIE HD |FR| FRANCE 3 NOA HD |FR| COMEDY CENTRAL HD |FR| 6TER HD |FR| VIAGRANDPARIS |FR| M6 HD |FR| CANAL 31 |FR| TF1 SERIES FILMS HD |FR| CANAL 8 HD |FR| TFX HD |FR| CLIQUE TV HD |FR| RTL 9 HD |FR| EQUIPE 21 HD |FR| TEVA HD |FR| IDF 1 |FR| TMC HD |FR| OLYMPIA HD |FR| W9 HD |FR| KTO |FR| ARTE HD |FR| BOOSTER TV HD |FR| NON STOP PEOPLE HD |FR| LEMAN BLEU HD |FR| NOVELAS TV HD |FR| CANAL 9 HD |FR| ONE TV HD |FR| THE SWIZZ HD |FR| ROUGE TV HD |FR| OLTV ##### |FR|HD| CH. CANAL+ ##### |FR| FLIX MOVIES HISTORIQUE HD |FR| CANAL+ HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES DOCUMENTAIRE |FR| CANAL+ SPORT HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ANIMATION HD |FR| CANAL+ PREMIER LEAGUE HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JASON STATHAM |FR| CANAL+ SERIE HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ANGELINA JOLIE |FR| CANAL+ FAMILY HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES TOM CRUISE |FR| CANAL+ DECALE HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES MORGAN FREEMAN |FR| CANAL+ CINEMA HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JACKIE CHAN |FR| CANAL+ FORMULE1 HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES VAN DAMME |FR| CANAL+ MOTOGP HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JOHN TRAVOLTA |FR| CANAL+ TOP14 HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES NICOLAS CAGE ##### |FR|HD| CINEMA ##### |FR| FLIX MOVIES MEL GIBSON |FR| FLIX MOVIES HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ROBERT DE NIRO |FR| FLIX MOVIES ACTION HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JIM CARREY |FR| FLIX MOVIES DRAMA HD |FR| ACTION HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ROMANCE HD |FR| OCS MAX HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES COMEDY |FR| OCS CITY HD -

Azam Pure Tshs. 12,000 Azam Plus Tshs. 20,000

Azam Pure Tshs. 12,000 1 Azam Info Channel Tanzania 2 Azam One Tanzania 3 Azam Two Tanzania 4 Sinema Zetu Tanzania 5 TBC 1 Tanzania 6 CHANNEL 10 Tanzania 7 CLOUDS TV Tanzania 8 ITV Tanzania 9 EATV Tanzania 10 ZBC-2 Tanzania 11 Zanzibar TV Tanzania 12 Star TV Tanzania 13 KBC Kenya 14 CITIZEN Kenya 15 K24 Kenya 16 NTV Kenya 17 KTN Kenya 18 QTV Kenya 19 UBC Uganda 20 WBS Uganda 21 NTV Uganda Uganda 22 NBS TV Uganda 23 Bukedde TV - 1 Uganda 24 Bukedde TV - 2 Uganda 25 Urban TV Uganda 26 TV West Uganda 27 MBC - Malawi Tv Malawi Azam Plus Tshs. 20,000 1 Azam Info Channel Tanzania 2 Azam One Tanzania 3 Azam Two Tanzania 4 Sinema Zetu Tanzania 5 TBC 1 Tanzania 6 CHANNEL 10 Tanzania 7 CLOUDS TV Tanzania 8 ITV Tanzania 9 EATV Tanzania 10 ZBC-2 Tanzania 11 Zanzibar TV Tanzania 12 Star TV Tanzania 13 KBC Kenya 14 CITIZEN Kenya 15 K24 Kenya 16 NTV Kenya 17 KTN Kenya 18 QTV Kenya 19 UBC Uganda 20 WBS Uganda 21 NTV Uganda Uganda 22 NBS TV Uganda 23 Bukedde TV - 1 Uganda 24 Bukedde TV - 2 Uganda 25 Urban TV Uganda 26 TV West Uganda 27 MBC - Malawi Tv Malawi 28 ETV - SOUTH AFRICA ENTERTAINMENT 29 FOX SPORTS SPORTS 30 MSC SPORTS 31 KOMBAT SPORTS SPORTS 32 MBC 2 Movies - English Block Busters 33 MBC ACTION Movies - English Action 34 MBC Max Movies - English Block Busters 35 MBC Power Plus ENTERTAINMENT 36 African Movie Channel Movies - African Block Busters 37 MTV BASE Music 38 LANDSCAPE Music 39 Box Africa Music 40 FINE LIVING Life Style 41 OUT DOOR LIVING Life Style 42 NAT GEO GOLD Wild Life 43 Discovery Science Science 44 Discovery Investigation Investigation -

Liste Des Canaux HD +

Liste des Canaux HD + - Enregistrement & programmation des enregistrements de chaînes (non-fonctionnel sur boîte Android / Smart Tv) - Le seul iptv offrant la fonction marche arrière sur vos canaux préférés - Vidéo sur demande – Films – Séries – Spectacle – Documentaire (Français, Anglais et Espagnole) Liste des canaux FRANÇAIS QUEBEC • TVA • TVA WEST • V TELE • TELE QUEBEC • LCN • MOI & CIE • CANAL D • RADIO CANADA • RADIO CANADA FREE • RDI • RDI FREE • CANAL SAVOIR • AMI TELE • UNIS TV • CANAL VIE • CASA • MUSIQUE PLUS • ZESTE • CANAL INVESTIGATION • CANAL D • ADDICK TV • SERIE + • Z TELE • VRAK • RDS • TVA SPORT • TVA SPORT 2 • RDS 2 • MAX • HISTORIA • PRISE 2 • SUPER ECRAN 1 • SUPER ECRAN 2 • SUPER ECRAN 3 • SUPER ECRAN 4 • ARTV • ICI EXPLORA • CINE-POP • EVASION • YOOPA • TELETOON *** AJOUT DE CANAUX A CHAQUE MOIS *** HORS QUÉBEC • France • TF1 • TFI LOCAL TIME -6 • M6 • M6 LOCAL TIME -6 • FRANCE 2 • FRANCE 3 • FRANCE 3 LOCAL TIME -6 • FRANCE 4 • FRANCE O • FRANCE 5 • ARTE • LCI • TV5 • TV5 MONDE • EURONEWS • BFM • BFM BUSINESS • FRANCE INFO • FRANCE 24 • CNEWS • HD1 • 6TER • W9 • W9 LOCAL TIME -6 • C8 • C8 LOCAL TIME -6 • 13 EIME RUE • PARIS PREMIERE • TEVA • COMEDIE • E! • NUMERO 23 • AB1 • TV BREIZH • NON STOP PEOPLE • NT1 • TCM CINEMA • TMC • CANAL + • CANAL + LOCAL TIME -6 • CANEL + CINEMA • CANAL + SERIES • CANAL + FAMILY • CANAL + DECALE • CINE + PREMIER • CINE + FRISSON • CINE + EMOTION • CINE + CLUB • CINE + CLASSIC • CINE FAMIZ • CINE FX • C STAR • CINE POLAR • OCS CITY • OCS MAX • OCS CHOC • OCS GEANT • GAME ONE • ACTION -

Al Masar Ajial Kids MBC HD Al Mawseleya Al Danah Kids MBC

Name Al Masar Ajial Kids MBC HD Al Mawseleya Al Danah Kids MBC Drama HD Ishtar UNRWA MBC Drama + Nart TV Taha MBC Bollywood HD Al Masreyah 1 Kidzinia MBC 4 HD Al Masreyah 2 Karameesh MBC 2 HD Palestine Semsem MBC Max HD Palestine Live Toyor Al Iraq MBC Variety HD Prime TV Hodhod Tv MBC Action HD Al Aqsa Mody Kids MBC 3 HD Palestine Al Koky Kids Yawm MBC Al Kofyah Mickey Channel MBC Maser Awdeh Sat7 Kids MBC Maser 2 Ma3an TV Nour Kids MBC 2 Al Salam TV Koogi Kids MBC Max Al Falastiniah Berbere Jeunesse MBC Action NBC TV Pelistanik MBC Drama Palastinian TV Bein Sports HD MBC Bollywood Al Quds Bein Sports News MBC 4 Musawa TV Dubai sport 1 Rotana Aflam HD Al Kitab Sharqa Sports Rotana Cinema Al Araby Abu Dhabi Sports 1 Rotana Cinema Eygpt Al Araby 2 Abu Dhabi Sports 2 Rotana Masriya Al Jamahriah TV Abu Dhabi Sports 3 Rotana Classic Libya TV Abu Dhabi Sports 4 Rotana Khalija Libya Alrasmiah Abu Dhabi Sports 5 See VII First Libya One Abu Dhabi Sports 6 See VII Shamiyeh Libya Al Watan MBC Sport 1 See VII Beelink Tobactos TV MBC Sport 2 See VII Drama Al Naba Lybia MBC Sport 3 Bein Movies 1 Libya MBC Sport 4 Almustaqbal Bein Movies 2 Libyas Channel Saudi Sport Fox Movies Action Libya Alhrar Oman Sport FX HD Libya 218 Kuwait Sport Fox Family Movies Tunisia National Kuwait Sport 1 Plus ART Cinema Tunisia National Al Kas 1 2 ART Aflam 1 Tunisna Al Kas 2 ART Aflam 2 Al Janoubia DMC Sport ART Hikayat 1 Elhiwar Tounsi ON Sport ART Hikayat 2 M Tunisia Al Ahly TV DMC First TV Al Hadaaf DMC Drama Nessma Iraq Sport CBC Zitouna TV Jordan Sport CBC Drama -

Jordanian Children's Attitudes Toward Children's Satellite Channels

أ Jordanian Children's Attitudes Toward Children's Satellite Channels 2010 أ ب ج 53 د ِ 2 5 8 8 9 10 10 11 13 15 16 17 18 20 20 و 22 23 24 30 34 Mbc3 35 36 38 39 40 40 41 42 53 61 62 63 64 64 65 66 67 67 70 103 108 ص 62 669 1 67 2 669 70 3 669 72 4 669 73 5 669 74 669 6 75 7 76 8 77 9 669 78 10 669 79 11 669 79 12 80 13 669 81 14 669 ح 109 1 110 2 120 2009 3 ط 12 43603 669 2009 ي أعلى Mbc3 Mbc3 mtv Arabic 91 79 ك 8.7 98.5 ل "Trends of Jordanian children towards children's TV channels" Preparation (Mohammad Hafez) (Mohammad Jawad) Hafez Jaber Supervised by Prof. Dr. Tayseer Abu Arjah Abstract This study is being aimed for recognizing the tendencies of Jordanian children towards the children's Satellite TV channels, the habits, styles of watching and seeing of the favorite programs for the children displayed and shown through these channels. This study was based on a descriptive approach as a questionnaire was designed and distributed to a random sample of children in the schools of the capital Amman. The study community was constituted of all children who are included in the seventh grade, being of age 12 years. They are 43603 boys and girls in schools relating to the First, Second, Third and Fourth Directorate of Education of the capital Amman, in addition to the Directorate of the Central Desert and the Special Education from the second quarter of 2009, and the study was formed of 669 students as a sample. -

Mark Progress in 3 Murder Probes Mr

Weather Mr. MEBAM >,.^w I ky tftenma. Hifh ta torn- at the shore. Fair, quite winn and kuuH Red Bank Area J tasufht and Tuesday. (SM weatfc- Copyright-The Red Bank Register, lac 1966. il). MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOME NEWSPAPER FOR 87 YEARS DIAL 7414)010 InoM tattr. VMU* tfcnoch rtUmt. turm* Qua fMtst PAGE ONE VOL. 89, NO. 35 raid M 8*4 td «M *t AddWeaJ MSUM omw. MONDAY, AUGUST 15, 1966 7C PER COPY Demands Board Tenure for Keansburg Teacher Sept. 1 Prexy Resign KEANSBURG - Board of Education finance com<nit- See Currie Reinstated by State Order tee chairman John jr. Syan Friday angrily called for By JAMES M. NEILLAND 60 days notice to the teacher be- Questioned specifically on the employment is effective Sept. 1. this assertion, claiming tenure Is hundreds and hundreds of people the resignation of board TRENTON — Fired Keansburg fore the contract rescission be- meaning of "employment on the That is the date he obtains ten- obtained upon issuance of the who have fought for me. president Mri. Mar.jaiet teacher Robert T. Currie will be comes effective. first day of the fourth succes- re." contract for the fourth year and "I will be in my classroom on Boyle. back at his job — in Keansburg— With the July 8 date as the sive academic year," Mr. Glas- The other two methods of ob- completion of three years' em- schedule." Mr. Ryan declared: next month. start of the 60-day period, it pey declared: taining tenure concern teachers ployment. Questioned on board president "I am convinced that, un- He will obtain tenure Sept. -

Full Guide W Covers.Pdf

2019 NAVY men’s LACROSSE GENERAL INFORMATION The Naval Academy Table of Contents Location Annapolis, Md. The Record Book Founded October 10, 1845 2019 Outlook Navy’s 100-Point Scorers 57-58 Enrollment 4,400 Quick Facts 1 Career Leaders 59 Nickname Midshipmen or Mids 2019 Head Shots 2-3 Single-Season Leaders 60 Colors Navy Blue and Gold 2019 Rosters (Alphabetical / Numerical) 4 Single-Game Leaders 61-62 Conference Patriot League Miscellaneous Team & Individual Records 63 Superintendent Vice Adm. Ted Carter, USN Midshipmen Profiles Class Records 64 Director of Athletics Chet Gladchuk Midshipmen Profiles 5-22 Largest Margins - Victory/Defeat 65 Coaching Staff Rankings History 66-70 Navy Lacrosse Head Coach Rick Sowell 23-25 All-Time Season Openers 71 Home Field Associate Head Coach Ryan Wellner 26 Memorable Navy Lacrossse Games 72 Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium Assistant Coach Rob Camposa 27 Navy’s NCAA Tournament History 73-74 Surface (Capacity) FieldTurf (34,000) Volunteer Assistant Coach Spencer Parks 27 Navy’s NCAA Tournament Statistics 75-76 2018 Overall Record 9-5 Director of PE Operations Mark Goers 28 Navy’s NCAA Tournament Record Holders 77 Home: 4-1 • Away: 5-2 • Neutral: 0-2 2018 Patriot League Record 7-1 2019 Opponents Tradition Home: 3-1 • Away: 4-0 • Neutral: 0-0 All-Time Series Records 29 The History of Navy Lacrosse 78-81 Patriot League Finish T-First Army-Navy Rivalry 30 Navy’s National Championship Teams 82-84 Patriot League Tournament All-Time Series Records by Conference 41 Military Award Winners 85 • L, 9-8 OT, vs. -

ART Channels Arab Mini Package

ATN Arabic TV channels There are no translations available. ATN network - TV channels ART channels EN: Sold separately, suitable for all ATN IPTV boxes (XTV.106 en XTV.125). NL: Apart verkocht, geschikt voor alle ATN IPTV boxen (XTV.106 en XTV.125). Arab mini package EN: ATN network Arab mini TV package with 200 TV channels. If you wish more, than please go for the normal Arab TV package including other Middle East TV channels. Note: you can't upgrade an Arab mini TV package to a normal TV package, as you would need in this case a new ATN receiver. NL: ATN network Arab mini TV pakket met meer dan 200 TV kanalen. Indien u meer kanalen wenst, kies dan voor de normale Arab TV pakket die ook andere TV kanalen uit het Midden Oost bevat. Let op, u kunt dit pakket niet upgraden naar een normaal TV pakket. Hiervoor heeft u een nieuwe ATN ontvanger nodig. Arab medium package EN: ATN network Arab medium TV package met honderden TV kanalen. NL: ATN network Arab medium TV pakket met honderden TV kanalen. Aljazeera Misr Ebalad Althakafia Somalisat TRT 6 Alarabiya Misr Zeaya Bedaya Somali National Tv Tek Rumeli TV BBC Arabic TRT Arabia Zweina Baladna Kalsan tv Rojhelat Al-Mayadeen TRT Arabia TS Jordan Ifilm Arabic NTV Al Alam - WNN Teleliban Jordan Sport Ifilm English NTV Sport Russia Alyaum LBC Falestin Orient News Speeda Al-hurra Iraq LDC Lebanon Alola Abt Yemen TV Komala TV CNBC Arabia LDC Lebanon TS Al Mergab Yemen Shabab Halaba TV Sky New Arabia Future Al Magharibia Sheba TV Newroz TV France24 Arabic Future TS Maghreb 1 Aden Tv Super TV STAR Future