Reasonable Accommodation, Affirmative Action, Or Both?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disability Rights 17

Filing a Complaint 20. Can I file a complaint with OFCCP and the KNOW YOUR RIGHTS Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Disability Rights 17. What can I do if I believe my employer (EEOC)? discriminated against me because of my Yes, if you file with both OFCCP and EEOC, your disability? complaint will be investigated by the appropriate agency. In some instances, OFCCP and EEOC may employers doing business with the You can file a complaint with OFCCP. You do not decide to work together to investigate your complaint. OFCCP Protects Individuals with need to know with certainty that your employer is a Federal Government to discriminate Disabilities from Discrimination against job applicants and employees federal contractor or subcontractor in order to file a OFCCP generally keeps complaints filed against based on disability. This means that complaint. federal contractors that allege discrimination based 1. What is employment discrimination based these employers cannot discriminate on disability. OFCCP generally keeps complaints on a person’s disability? against you when making decisions 18. How do I file a complaint with OFCCP? filed against federal contractors where there appears on hiring, firing, pay, benefits, job to be a pattern of discrimination that affects a Employment discrimination based on a person’s assignments, promotions, layoffs, You may file a discrimination complaint by: group of employees or applicants, and those that disability generally occurs when an employer treats training, and other employment related allege discrimination based on a person’s sexual a qualified job applicant or employee unfavorably activities. • Completing and submitting a form online through orientation, gender identity, or protected veteran in any aspect of employment because the individual OFCCP’s Web site; or status. -

The Americans with Disabilities Act As Welfare Reform

William & Mary Law Review Volume 44 (2002-2003) Issue 3 Disability and Identity Conference Article 3 February 2003 The Americans with Disabilities Act as Welfare Reform Samuel R. Bagenstos Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Disability Law Commons Repository Citation Samuel R. Bagenstos, The Americans with Disabilities Act as Welfare Reform, 44 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 921 (2003), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol44/iss3/3 Copyright c 2003 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT AS WELFARE REFORM SAMUEL R. BAGENSTOS* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................... 923 I. THE CRITIQUE: BETRAYING THE PROMISES OF THE ADA? ... 930 A. The Definition of "Disability ..................... 930 B. JudicialEstoppel Cases ........................... 936 1. The Basic Problem ............................. 936 2. The Cleveland Decision ......................... 941 3. The Cleveland Aftermath ........................ 943 4. The Critique .................................. 948 C. ReasonableAccommodation Cases .................. 949 II. THE ADA AND THE WELFARE REFORM ARGUMENT ........ 953 A. The Welfare Reform Argument and the ADA .......... 957 1. Early Signs: The Commission on Civil Rights and National Council on the HandicappedReports... 958 2. The Welfare Reform Argument in the Congressional Hearings:Members of Congress Build the Case ...... 960 * Assistant Professor of Law, Harvard Law School. Betsy Bartholet, Matthew Diller, Christine Jolls, Gillian Metzger, Frank Michelman, Martha Minow, Richard Parker, Bill Stuntz, David Westfall, Lucie White, and, as always, Margo Schlanger, offered very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this Article. Thanks to Lizzie Berkowitz, Carrie Griffin, Scott Michelman, Nate Oman, and Lindsay Freeman Wiley for their excellent research assistance. -

Reasonable Accommodation Handbook Chpt 2 Statutory Requirements

Handbook 7855.1 Procedures for Providing Reasonable Accommodation for Individuals with Disabilities CHAPTER 2. STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS/ POLICY STATEMENT/MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITIES 2-1. STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS A. Section 501 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended, 1. Prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in Federal employment and requires the Federal Government to engage in Affirmative Employment for Individuals with Disabilities. 2. Requires Federal employers not to discriminate against qualified job applicants or employees with disabilities. Federal employers shall ensure that their policies do not unnecessarily exclude or limit individuals with disabilities because of a job's structure or because of architectural, transportation, communication, procedural, or attitudinal barriers. 3. Requires employers to make "reasonable accommodation" to the known physical or mental limitations of qualified applicants and employees with disabilities unless the agency can demonstrate that the accommodation would impose an undue hardship on the operation of its program. 4. Prohibits the use of selection criteria and standards which tend to screen out people with disabilities, unless such criteria have been determined through a job analysis to be job-related and consistent with business necessity, and an appropriate individualized assessment indicates that the job applicant cannot perform the essential functions of the job, with or without reasonable accommodation. B. Executive Order 13164 dated July 26, 2000, " Requiring Federal Agencies to Establish Procedures to Facilitate the Provision of Reasonable Accommodation", mandates Federal agencies, among other things, to establish effective written procedures to facilitate the provision of reasonable accommodation, and submit Agency Reasonable Accommodation procedures to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission by July 26, 2001. -

Invisible Disabilities and the ADA

EMPLOYMENT Legal Briefings Invisible Disabilities and the ADA By Equip for Equality1 When someone has an “invisible disability,” such as diabetes, epilepsy, mental health disabilities, traumatic brain injury, or HIV/AIDS, the “invisible” nature of the disability raises unique issues for both the employer and the employee. This legal brief will review the legal issues and court decisions when “invisible” disabilities are at issue. The focus of this legal brief will be on:2 1. Whether the condition constitutes a disability under the ADA as amended; 2. Medical inquiries, examinations, and disability disclosure; 3. Confidentiality; 4. Disabilities must be known by the employer to establish an ADA violation; and 5. Disability harassment. I. Does the Condition Constitute a Disability Under the ADA? The first question in any ADA case is whether the employee is a person with a disability under the ADA. This question is more liberally construed under the ADA Amendments Act of 2008 (ADAAA), which went into effect in 2009.3 The ADAAA provides greater protections for individuals with invisible disabilities due to several changes made in the law. These changes include: liberalizing the definition of disability, removing the requirement that mitigating measures be taken into account when assessing whether an individual has a substantial limitation, and adding additional major life activities including a separate category that includes “major bodily functions.” Congress’ primary focus in enacting the ADAAA was to make clear that the Supreme Court and lower courts had unduly narrowed the definition of disability and, as a result, many people with impairments that it had intended to be covered, had been deemed not to have an ADA disability.4 A. -

Religious Diversity and Reasonable Accommodation in the Workplace In

Article International Journal of Discrimination and the Law Religious diversity 1–29 ª The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permission: and reasonable sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1358229113493691 accommodation in jdi.sagepub.com the workplace in six European countries: An introduction Veit Bader1, Katayoun Alidadi2 and Floris Vermeulen1 Abstract After a period during which many in the West, especially Europe, expected religion to progressively fade away from public life, for various reasons religion has, over the last two decades, re-established itself as a phenomenon to be reckoned with in the globa- lized West. It has also become a favoured research topic for, amongst others, social scientists and legal scholars. While the European Union (EU) has a limited competency when it comes to matters of religion, in 2000 an important Directive was adopted, pro- hibiting discrimination on the basis of religion or belief in the area of employment. The EU’s interest, however, extends beyond the anti-discrimination framework, explaining why in 2010 it funded a three-year multidisciplinary project on religious diversity and secularism in Europe (RELIGARE). One of the areas of investigation, illustrating the various tensions that arise when religious claims are formulated in 21st-century Europe, concerned the area of employment and labour relations. This article provides an intro- duction – philosophical, legal and sociological – to a special issue with six contributions drawing from sociological data collected within the RELIGARE project. From a socio- logical perspective, these contributions illustrate the challenges and tensions raised by religion and belief both in secular workplaces (the individual religious freedom cluster)and 1University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium Corresponding author: Katayoun Alidadi, Institute for Human Rights and Critical Studies, Law Faculty, Catholic University of Leuven, Tiensestraat 41, Box 3416, Leuven 3000, Belgium. -

“Reasonable Accommodation” and “Accessibility”: Human Rights Instruments Relating to Inclusion and Exclusion in the Labor Market

societies Article “Reasonable Accommodation” and “Accessibility”: Human Rights Instruments Relating to Inclusion and Exclusion in the Labor Market Marianne Hirschberg * and Christian Papadopoulos Received: 28 August 2015; Accepted: 6 January 2016; Published: 16 January 2016 Academic Editor: Gregor Wolbring Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Applied Sciences Bremen, Neustadtswall 30, 28199 Bremen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-421-5905-2189; Fax: +49-421-5905-2753 Abstract: Ableism is a powerful social force that causes persons with disabilities to suffer exclusion. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is based on the human rights principles of equality and freedom for all people. This Convention contains two human rights instruments: the principle of accessibility and the means of reasonable accommodation, which can be used to protect the human rights of disabled persons. The extent to which they are used depends on whether the state implements the Convention adequately and whether companies accept their responsibility with respect to employing disabled persons and making workplaces available and designing them appropriately. Civil society can demand the adequate implementation of the human rights asserted in the CRPD and, thus, in national legislation, as well. A crucial point here is that only a state that has ratified the Convention is obliged to implement the Convention. Civil society has no obligation to do this, but has the right to participate in the implementation process (Art. 4 and Art. 33 CRPD). The Convention can play its part for disabled persons participating in the labor market without discrimination. -

PPM 3100-29, Reasonable Accommodations for Individuals

PPM 3100-29 Reasonable Accommodations for Section: Management Subject: Individuals With Disabilities To: All OCC Employees Purpose This issuance revises Policies and Procedures Manual (PPM) 3100-29, “Reasonable Accommodations for Individuals With Disabilities,” dated August 20, 2019. This PPM explains the policy and procedures for processing requests for reasonable accommodation and, when appropriate, for providing voluntary job modification or accommodation to Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) employees and job applicants with disabilities. The whistleblower statement in this PPM was updated in accordance with 5 USC 2302(b)(13) regarding whistleblower protection. References • 5 USC 2302, “Prohibited Personnel Practices” • Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (29 USC 791, et seq., as amended) • Executive Order 13164, “Requiring Federal Agencies to Establish Procedures to Facilitate the Provision of Reasonable Accommodation,” July 26, 2000 • Americans With Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 2008 (ADAAA), Pub. L. 110-325 ADAAA, effective 2009 • U.S. Department of the Treasury Transmittal TN-12-002, “Interim Voluntary Modification and Reasonable Accommodation Policy and Procedures,” November 15, 2011 • U.S. Department of the Treasury, Civil Rights & Diversity (CRD), CRD-008 Policy for Personal Assistance Services, dated July 20, 2018 • U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), “Policy Guidance on Executive Order 13164: Establishing Procedures to Facilitate the Provision of Reasonable Accommodation,” October 20, 2000 • EEOC, -

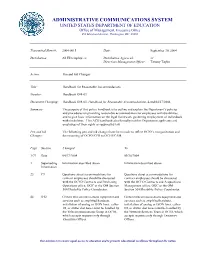

Handbook for Reasonable Accomodations

ADMINISTRATIVE COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEM UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Management, Executive Office 400 Maryland Avenue; Washington, DC 20202 Transmittal Sheet #: 2004-0015 Date: September 30, 2004 Distribution: All ED employees Distribution Approved: /s/ Directives Management Officer: Tammy Taylor Action: Pen and Ink Changes Title: Handbook for Reasonable Accommodations Number: Handbook OM-03 Document Changing: Handbook OM-03, Handbook for Reasonable Accommodations, dated 04/27/2004. Summary: The purpose of this policy handbook is to outline and explain the Department’s policies and procedures on providing reasonable accommodation for employees with disabilities, and to give basic information on the legal framework governing employment of individuals with disabilities. This ACS handbook also formally notifies Department applicants and employees of their rights as required by law. Pen and Ink The following pen and ink changes have been made to reflect OCIO’s reorganization and Changes: the renaming of OCFO/CPO to OCFO/CAM. Page Section Changed To 1-72 Date 04/27/2004 09/30/2004 1 Superseding Information described above Information described above Information 23 C9 Questions about accommodations for Questions about accommodations for contract employees should be discussed contract employees should be discussed with the OCFO Contracts and Purchasing with the OCFO Contracts and Acquisitions Operations office, OGC or the OM Section Management office, OGC or the OM 504/Disability Policy Coordinator. Section 504/Disability Policy Coordinator. 44 D12 Certain telecommunications equipment and Certain telecommunications equipment and services such as amplified handsets, services such as amplified handsets, installation of analog or ISDN lines, caller- installation of analog or ISDN lines, caller- ID, or stutter dial tones must be handled by ID, or stutter dial tones must be handled by the Telecommunications Group in OCIO, the Network Services Team in OCIO, which which accepts requests only through accepts requests only through Executive Executive Offices. -

Reasonable Accommodations in the Workplace

APSU’s Employer Obligations under Disability Rights Laws Sheila Bryant Director of Equal Opportunity & Affirmative Action Office of Equity, Access, and Inclusion [email protected] Legal Foundation Disability Laws/Policy • Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was the first piece of civil rights legislation to address the rights of people with disabilities. The Rehabilitation Act made it illegal for programs that receive federal funding (such as universities) to discriminate on the basis of a disability. • The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, as amended, is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination in employment, public services and accommodations, and telecommunications. It applies to employers with 15 or more employees. • APSU POLICY 6:004: Discrimination and Harassment Based on Protected Categories other than Sex 2 Policy Statement In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, as amended and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504, no qualified person will be denied access to, participation in, or the benefits of, any program or activity operated by Austin Peay State University (APSU) because of disability. APSU will not discriminate against qualified individuals with disabilities in employment practices and activities, including, but not limited to, application procedures, hiring, tenure, promotion, advancement, termination, training, compensation and benefits. Additionally, APSU will not discriminate against a qualified individual because of the known disability of another individual -

SEC Accommodation Procedures- 508 Friendly Edition

SEC Accommodation Procedures Office of Human Resources SEC Disability Accommodation Process Accommodations enable people with physical or mental disabilities to have access to employment opportunities and public programs equivalent to that of non-disabled people. Accommodations include equipment and services, modified work environments, locations and schedules and restructured jobs. Reassignment to a suitable vacant position is the accommodation of last resort, available only when no other accommodations will work. Federal Law Requires Employers to Provide Reasonable Accommodations to Qualified Persons with Disabilities The Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended by the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act, requires federal agencies to reasonably accommodate qualified individuals with covered disabilities. Reasonable accommodations do not include accommodations that would cause undue hardship to the employer. Individuals have covered disabilities if they have physical or mental conditions that substantially impair their ability to perform major life activities (such as seeing, hearing, walking and speaking). Individuals are not disabled if their conditions do not substantially impair their ability to perform major life activities when they are compared to most other people in the general population. Individuals are not disabled if their condition is likely to last less than three months regardless of how severely” it impacts their ability to perform major life activities. Individuals are “qualified when they meet the education, experience and licensing requirements of the position and can perform the essential functions of the position with--or without--reasonable accommodations. SEC’s Policy and Procedures Regarding Accommodations Requests SEC’s policy is to reasonably accommodate qualified persons with disabilities covered by the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 when they request accommodations and accommodations will not cause the SEC undue hardship. -

Ten Steps to Accessibility

Ten Steps to Accessibility Step 1: Know the Laws and How They Apply to Your Organization, Patrons and Audiences with Disabilities [link to Step 1] Step 2: Provide Individuals with Equal Employment Opportunities[link to Step 2] Step 3: Designate an Accessibility Coordinator for Your Organization [link to Step 3] Step 4: Create an Access Advisory Committee [link to Step 4] Step 5: Adopt a Policy Statement About Your Organization’s Commitment to Accessibility and Establish a Grievance Procedure [link to Step 5] Step 6: Evaluate Your Organization’s Accessibility: The Arts and Humanities Accessibility Checklist [link to Step 6] Step 7: Develop an Access Plan [link to Step 7] Step 8: Train Your Staff, Board, Panelists, Grantees and Constituents [link to Step 8] Step 9: Enforce 504/ADA Compliance within Your Organization [link to Step 9] Step 10: Promote and Market Your Accessibility [link to Step 10] 16 STEP 1: Know the Laws and How They Apply to Your Organization, Patrons and Audiences with Disabilities Guidance About Federal Law and Legal Requirements Section 504 Regulations and the Americans with Disabilities Act ADA Publications ADA and 504 Resource Directory Guidance About Federal Laws and Legal Requirements Section 504 and the ADA are standard legal requirements, which are intended to provide people with disabilities the same opportunity to be employed and enjoy your organization's programs, services and facilities as non-disabled people. By law, all programs should be accessible. The four major requirements of accessibility laws are: 1) Non-discrimination 2) Equal opportunity (and the provision of any reasonable modifications, auxiliary aids or services necessary to achieve it) 3) Basic standard of architectural access 4) Equal access to employment, programs, activities, goods and services Access efforts should not simply respond to legal requirements, but celebrate the positive benefits of full access to cultural activities, and the opportunity to serve and educate all segments of the public. -

Disability Law and the Disability Rights Movement for Transpeople

Disability Law and the Disability Rights Movement for Transpeople Zach Strassburgert ABSTRACT: Existing disability law is fairly successful at protecting transsexual people from legal discrimination, but the stigma and medicalization of disability prevent further efforts that could make disability a more useful frame for transgender activism. Furthermore, disability law is underinclusive in that genderqueers and others for whom a diagnosis of gender identity disorder (GID) is impractical cannot access current disability law protections. Still, the disability rights movement can offer possible legal change and can provide important narratives for reimagining differences and rethinking accommodations that will create less restrictive disability and other civil rights law to protect transgender and transsexual people in the long term. This Note imagines a new disability law, which defines disability socially, centers on self-identification, and changes the legal landscape of antidiscrimination protections for trans and gender-variant communities. I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 338 II. BENEFITS OF DISABILITY LAW FOR TRANSSEXUALS......... ........... 340 III. DISABILITY LAW FOR GENDER-VARIANT NONTRANSSEXUALS ........ 347 IV. CRITIQUES OF CURRENT EFFORTS TO USE DISABILITY LAW....................359 V. THE DISABILITY RIGHTS MOVEMENT'S LESSONS FOR FRAMING TRANSGENDER RIGHTS...............................365 VI. CONCLUSION ........................................... ...... 374 t J.D., Yale Law School, Class of 2012; Equal Justice Works Fellow at KidsVoice in Pittsburgh, PA. For comments on the draft, I owe thanks to Reva Siegel, Amy Kapczynski, Peter Heisler, and Kate Jenkins. Copyright 0 2012 by the Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 338 Yale Journal of Law and Feminism [Vol. 24:2 I. INTRODUCTION This Note argues that the use of disability law for transsexualsl should be continued despite the stigma and medicalization 2 of disability, and that disability as a framework should be expanded to include nontranssexuals as well.