The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School the College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil and Gas Industry Investments in the National Rifle Association and Safari Club International Reshaping American Energy, Land, and Wildlife Policy

JOE RIIS JOE Oil and Gas Industry Investments in the National Rifle Association and Safari Club International Reshaping American Energy, Land, and Wildlife Policy By Matt Lee-Ashley April 2014 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Oil and Gas Industry Investments in the National Rifle Association and Safari Club International Reshaping American Energy, Land, and Wildlife Policy By Matt Lee-Ashley April 2014 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 3 Oil and gas industry investments in three major sportsmen groups 5 Safari Club International 9 The National Rifle Association 11 Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation 13 Impact of influence: How the oil and gas industry’s investments are paying off 14 Threats to endangered and threatened wildlife in oil- and gas-producing regions 19 Threats to the backcountry 22 Threats to public access and ownership 25 Conclusion 27 About the author and acknowledgments 28 Endnotes Introduction and summary Two bedrock principles have guided the work and advocacy of American sports- men for more than a century. First, under the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, wildlife in the United States is considered a public good to be conserved for everyone and accessible to everyone, not a commodity that can be bought and owned by the highest bidder.1 Second, since President Theodore Roosevelt’s creation of the first wildlife refuges and national forests, sportsmen have fought to protect wildlife habitat from development and fragmentation to ensure healthy game supplies. These two principles, however, are coming under growing fire from an aggressive and coordinated campaign funded by the oil and gas industry. As part of a major effort since 2008 to bolster its lobbying and political power, the oil and gas industry has steadily expanded its contributions and influ- ence over several major conservative sportsmen’s organizations, including Safari Club International, or SCI, the National Rifle Association, or NRA, and the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation. -

A Ambientação De Personagens Negros Na Marvel Comics: Periferia, Vilania E Relações Inter-Raciais

A AMBIENTAÇÃO DE PERSONAGENS NEGROS NA MARVEL COMICS: PERIFERIA, VILANIA E RELAÇÕES INTER-RACIAIS Amaro Xavier Braga Junior1 RESUMO: O trabalho faz um levantamento, com base em uma análise de conteúdo, dos personagens negros nos quadrinhos de super-heróis da editora Marvel Comics. Analisa sua inserção nos ambientes socialmente descritos e identifica, através de padrões quali-quantitativos, a situações de ambientação periférica destes personagens, heroicos e coadjuvantes. Questiona, através das publicações entre as décadas, a relação entre super-heróis e vilões negros; conclui fazendo uma varredura sobre as relações inter-raciais sexuais e afetivas surgidas neste campo dos quadrinhos. Palavras-chave: Discriminação Racial. Estereótipos. Quadrinhos. ABSTRACT: The study is a survey based on a content analysis of the black characters in comics superhero of Marvel Comics. Analyzes its insertion in the environments described socially and identifies, through qualitative and quantitative standards, the ambiance peripheral situations these characters, heroic and adjuncts. Questions, through publications between the decades, the relationship between superheroes and villains blacks; concludes doing a scan on interracial sexual and affective relations encountered in this field of comics. Keywords: Racial Discrimination. stereotypes. Comics. INTRODUÇÃO Para compreendermos o papel da identidade negra nos quadrinhos, além de analisar nossas próprias representações históricas, quase que obrigatoriamente, precisamos seguir pela história da Editora Marvel. Esta necessidade advém do grande impacto que os materiais desta editora tiveram (e ainda têm) sobre o mercado de quadrinhos no Brasil e a mentalidade dos quadrinhistas e quadrinhófilos brasileiros. Seus personagens e revistas são muito mais facilmente reconhecidos no imaginário popular do nosso país que as investidas de outras editoras e as publicações de outros países. -

Book Reviews.6

Page 85 BOOK REVIEWS Tartarus Press Strange Tales, ed. Rosalie Parker (North Yorkshire: Tartarus, 2003) & Wormwood: Literature of the Fantastic, Supernatural & Decadent, 16, 20032006 Dara Downey the horror genre is extremely limber, extremely adaptable, extremely useful; the author or filmmaker can use it as a crowbar to lever open locked doors or a small, slim pick to tease the tumblers into giving. The genre can thus be used to open almost any lock on the fears which lie behind the door […]. (Stephen King, Danse Macabre (1982), 163) When King is at his best, he can be remarkably adept at cutting to the core of the genre of which he is the selfproclaimed “King”. Nevertheless, however astute such isolated observations as the above comment might be, it is always possible to find another, equally astute observation, that both contradicts what he is saying and undermines whatever favourable impression of his analytical skills we may have. Elsewhere in Danse Macabre, for example, King states confidently that Henry James’ “The Turn of the Screw, with its elegant drawingroom prose and its tightly woven psychological logic, has had very little influence on the American masscult” of mainstream horror (Danse Macabre, 66). What this suggests is that the flexibility which he sees as the defining characteristic of horror has (for him at any rate) a breaking point, a suggestion well in line with his nearhysterical insistence that aesthetic values and intellectual rigour are antithetical to the aims and effects of the genre. It is precisely this sort of inverted snobbery that Tartarus Press are striving to overthrow. -

The Boone and Crockett Club on Fair Chase 9/5/2016

THE BOONE AND CROCKETT CLUB ON FAIR CHASE 9/5/2016 Why a Discussion on Fair Chase? All significant human activities are conducted under a set of ethical principles that guide appropriate behavior. Depending on the activity, these principles are molded into laws when specific behavior is required. Without ethics and laws, most activities would become unsafe and unacceptable to both those who participate in them and those who do not. Hunting is no different. It, too, has principles and laws that guide ethical behavior. In modern, devel- oped societies, there exists a general expectation that hunting be conducted under appropriate conditions—animals are taken for legitimate purposes such as food, to attain wildlife agency management goals, and to mitigate property damage. It is also expected that the hunting is done sustainably and legally, and that hunters conduct themselves ethically by showing respect for the land and animals they hunt. In the broadest sense, hunters are guided by a conservation ethic, but the most common term used to describe the actual ethical pursuit of a big game animal is “fair chase.” The concept of fair chase has been widely promoted for over a century by the Boone and Crockett Club, an organi- zation founded by Theodore Roosevelt in 1887 to work towards saving what was left of dwindling North American wildlife populations. The Club defines fair chase as “the ethical, sportsmanlike, and lawful pursuit and taking of any free-ranging wild, native North American big game animal in a manner that does not give the hunter an improper advantage over such animals.” Fair chase has become a code of conduct for the American sportsman, helped shape the foundation of many of our game laws, and is taught to new hunters as they complete mandatory certification courses. -

1 Updated: 1/4/2019 2:21 PM

1 HISTORICAL FILES, Subject and Biographical A – Miscellaneous Abert, James Actors and Actresses Adair, John Adams Papers Adams, Daniel (Mrs.) Adkins, Betty Lawrence African American Genealogy African American History African Americans African Americans – Indiana African Americans – Kentucky African Americans – Louisville Ahrens, Theo (Jr.) Ainslie, Hew Alexander, Barton Stone Ali, Muhammad Allensworth, Allen Allison, John S. Allison, Young E. - Jr. & Sr. Almanacs Altsheller, Brent Alves, Bernard P. American Heritage American Letter Express Co. American Literary Manuscripts American Revolution American Revolution - Anecdotes American Revolution - Soldiers Amish - Indiana Anderson, Alex F. (Ship - Caroline) Anderson, James B. Anderson, Mary Anderson, Richard Clough Anderson, Robert Anderson, William Marshall Anderson, William P. Updated: 1/4/2019 2:21 PM 2 Andressohn, John C. Andrew's Raid (James J. Andrews) Antiques - Kentucky Antiquities - Kentucky Appalachia Applegate, Elisha Archaeology - Kentucky Architecture and Architects Architecture and Architects – McDonald Bros. Archival Symposium - Louisville (1970) Archivists and Archives Administration Ardery, Julia Spencer (Mrs. W. B.) Ark and Dove Arnold, Jeremiah Arthur Kling Center Asbury, Francis Ashby, Turner (Gen.) Ashland, KY Athletes Atkinson, Henry (Gen.) Audubon State Park (Henderson, KY) Augusta, KY Authors - KY Authors - KY - Allen, James Lane Authors - KY - Cawein, Madison Authors - KY - Creason, Joe Authors - KY - McClellan, G. M. Authors - KY - Merton, Thomas Authors - KY - Rice, Alice Authors - KY - Rice, Cale Authors - KY - Roberts, Elizabeth Madox Authors - KY - Sea, Sophie F. Authors - KY - Spears, W. Authors - KY - Still, James Authors - KY - Stober, George Authors - KY - Stuart, Jesse Authors - KY - Sulzer, Elmer G. Authors - KY - Warren, Robert Penn Authors - Louisville Auto License Automobiles Updated: 1/4/2019 2:21 PM 3 Awards B – Miscellaneous Bacon, Nathaniel Badin, Theodore (Rev.) Bakeless, John Baker, James G. -

6.0 Consultation and Coordination

Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Final EIS Chapter 6.0 – Consultation and Coordination 6-1 6.0 Consultation and Coordination This EIS was conducted in accordance with NEPA requirements, CEQ regulations, and the DOI and BLM policies and procedures implementing NEPA. NEPA and the associated laws, regulations, and policies require the BLM to seek public involvement early in, and throughout, the planning process to develop a reasonable range of alternatives to PCW’s Proposed Action and prepare environmental documents that disclose the potential impacts of alternatives considered. Public involvement and agency consultation and coordination, which have been at the heart of the process leading to this draft EIS, were achieved through FR notices, public and informal meetings, individual contacts, media releases, and the project website. From the initial proposal of the project, the public and agencies have been approached for input on the project scope and development, as discussed in Chapter 1.0. This chapter describes this public involvement process as well as other key consultation and coordination. 6.1 Agency Participation and Coordination Specific regulations require the BLM to coordinate and consult with federal, state, and local agencies about the potential of the project and alternatives to affect sensitive environmental and human resources. The BLM initiated these coordination and consultation activities through the scoping process and has maintained them through regular meetings regarding key topics (e.g., alternatives and impact analyses) -

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOSEVELT, THEODORE 1858-1919 Gift of Paul C. Richards, 1976-1990; 1993 Note: Items found in Richards-Roosevelt Room Case are identified as such with the notation ‘[Richards-Roosevelt Room]’. Boxes 1-12 I. Correspondence Correspondence is listed alphabetically but filed chronologically in Boxes 1-11 as noted below. Material filed in Box 12 is noted as such with the notation “(Box 12)”. Box 1 Undated materials and 1881-1893 Box 2 1894-1897 Box 3 1898-1900 Box 4 1901-1903 Box 5 1904-1905 Box 6 1906-1907 Box 7 1908-1909 Box 8 1910 Box 9 1911-1912 Box 10 1913-1915 Box 11 1916-1918 Box 12 TR’s Family’s Personal and Business Correspondence, and letters about TR post- January 6th, 1919 (TR’s death). A. From TR Abbott, Ernest H[amlin] TLS, Feb. 3, 1915 (New York), 1 p. Abbott, Lawrence F[raser] TLS, July 14, 1908 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. ALS, Dec. 2, 1909 (on safari), 4 p. TLS, May 4, 1916 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. TLS, March 15, 1917 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. Abbott, Rev. Dr. Lyman TLS, June 19, 1903 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Nov. 21, 1904 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Feb. 15, 1909 (Washington, D.C.), 2 p. Aberdeen, Lady ALS, Jan. 14, 1918 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. Ackerman, Ernest R. TLS, Nov. 1, 1907 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. Addison, James T[hayer] TLS, Dec. 7, 1915 (Oyster Bay), 1p. Adee, Alvey A[ugustus] TLS, Oct. -

The Boone and Crockett Club on Conservation and Preservation

THE BOONE AND CROCKETT CLUB ON CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION Why a Discussion of Conservation and Preservation More people are engaging in and having a greater influence on natural resource issues than ever before through voter initiatives, public forums, and social media. They want to do what is best, yet are not necessarily familiar with the two primary approaches by which natural resources are managed— conservation and preservation. Conservation and preservation are terms everyone has heard of, but for many people they remain loosely defined and not well understood. There is a growing belief that “letting nature take its course” with no human interference is the best philosophy for the treatment of natural resources. Many are mistakenly or intentionally calling this way of thinking conservation, though it is more closely aligned with preservation. These misconceptions are helping to shift the management of natural resources from a successful “hands-on” conservation approach to a “hands-off” preservation approach, which is proving to have serious negative implications. Conservation and preservation are both concerned with protection and betterment of the environment, but they are based on different philosophies that produce different results. Conservation focuses on using and managing natural resources to benefit people, but in keeping within the limits of supply, regrowth, and change, both natural and human-influenced. It is the most widely used and accepted model for the management of natural resources, including wildlife, in North America. Preservation is a philosophy that generally views people as a negative influence on nature, and seeks to keep natural resources in a pristine state by limiting use and excluding active management by people. -

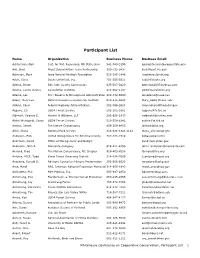

Participant List

Participant List Name Organization Business Phone Business Email Achterman, Gail Inst. for Nat. Resources, OR State Univ. 541-740-3190 [email protected] Ack, Brad Puget Sound Action Team Partnership 360-725-5437 [email protected] Ackelson, Mark Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation 515-288-1846 [email protected] Adair, Steve Ducks Unlimited, Inc. 701-355-3511 [email protected] Adams, Bruce San Juan County Commission 435-587-2820 [email protected] Adams, Laurie Davies Coevolution Institute 415-362-1137 [email protected] Adams, Les Ntn’l Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration 202-482-6090 [email protected] Addor, Mary Lou Natural Resources Leadership Institute 919-515-9602 [email protected] Adkins, Carol Federal Highway Administration 202-366-2024 [email protected] Agpaoa, Liz USDA Forest Service 202-205-1661 [email protected] Albrecht, Virginia S. Hunton & Williams, LLP 202-955-1943 [email protected] Alden Weingardt, Susan USDA Forest Service 510-559-6342 [email protected] Aldrich, James The Nature Conservancy 859-259-9655 [email protected] Allen, Diana National Park Service 314-436-1324 x112 [email protected] Anderson, Bob United Winegrowers for Sonoma County 707-433-7319 [email protected] Anderson, David Office of Management and Budget [email protected] Anderson, John R. Monsanto Company 919-821-9295 [email protected] Annand, Fred The Nature Conservancy, NC Chapter 919-403-8558 [email protected] Antoine, AICP, Todd Great Rivers Greenway District 314-436-7009 [email protected] Anzalone, Ronald D. Advisory Council on Historic Preservation 202-606-8523 [email protected] Arce, Mardi NPS, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial 314-655-1643 [email protected] Archuletta, Phil P&M Plastics, Inc. -

Technical Review 12-04 December 2012

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Technical Review 12-04 December 2012 1 The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation The Wildlife Society and The Boone and Crockett Club Technical Review 12-04 - December 2012 Citation Organ, J.F., V. Geist, S.P. Mahoney, S. Williams, P.R. Krausman, G.R. Batcheller, T.A. Decker, R. Carmichael, P. Nanjappa, R. Regan, R.A. Medellin, R. Cantu, R.E. McCabe, S. Craven, G.M. Vecellio, and D.J. Decker. 2012. The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 12-04. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Series Edited by Theodore A. Bookhout Copy Edit and Design Terra Rentz (AWB®), Managing Editor, The Wildlife Society Lisa Moore, Associate Editor, The Wildlife Society Maja Smith, Graphic Designer, MajaDesign, Inc. Cover Images Front cover, clockwise from upper left: 1) Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) kittens removed from den for marking and data collection as part of a long-term research study. Credit: John F. Organ; 2) A mixed flock of ducks and geese fly from a wetland area. Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS; 3) A researcher attaches a radio transmitter to a short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi) in Colorado’s Pawnee National Grassland. Credit: Laura Martin; 4) Rifle hunter Ron Jolly admires a mature white-tailed buck harvested by his wife on the family’s farm in Alabama. Credit: Tes Randle Jolly; 5) Caribou running along a northern peninsula of Newfoundland are part of a herd compositional survey. Credit: John F. Organ; 6) Wildlife veterinarian Lisa Wolfe assesses a captive mule deer during studies of density dependence in Colorado. -

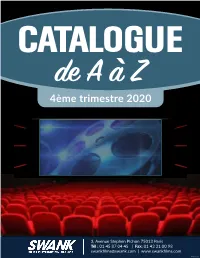

4Ème Trimestre 2020 Ccaattaalloogg

CATA L O G U E de A a Z uuee 4ème trimestre 2020 CCaattaalloogg 3, Avenue Stephen Pichon 75013 Paris Tél3, Avenue : 01 45Stephen 87 Pichon04 45 75013 | Paris Fax: 01 43 31 00 98 [email protected]él : 01 45 87 04 45 | Fax: 01 43 31 00 | 98 www.swankfilms.com [email protected] | www.swankfilms.com FRA96303 CATA L O G U E SWA N K de A a Z Titres Studio Année Titres Studio Année (500) jours ensemble The Walt Disney Company 2009 (S)ex List The Walt Disney Company 2011 # Pire soirée Sony 2017 007 Spectre MGM 2015 100, Les - Saison 1 Warner Bros. 2014 100, Les - Saison 2 Warner Bros. 2014 100, Les - Saison 3 Warner Bros. 2016 100, Les - Saison 4 Warner Bros. 2017 100, Les - Saison 5 Warner Bros. 2018 100, Les - Saison 6 Warner Bros. 2019 10 000 BC Warner Bros. 2008 1001 pattes The Walt Disney Company 1998 10 bonnes raisons de te larguer The Walt Disney Company 1999 10 Cloverfield Lane Paramount 2016 11'09''01: Onze minutes, neuf secondes, un cadre StudioCanal 2002 11 Commandements, Les Pathé Distribution 2003 11ème Heure, La Warner Bros. 2007 125 rue Montmartre Pathé Distribution 1959 127 heures Pathé Distribution 2010 12 chiens de Noël, Les First Factum LLC 2012 12 Rounds The Walt Disney Company 2009 13 Fantômes Sony 2001 13 fantômes de Scoobydou (Les) Warner Bros. 1985 13 hours Paramount 2016 15h17 pour Paris, Le (WB) Warner Bros. 2017 1900 Paramount 1976 1941 Sony 1979 1969 MGM 1988 1984 MGM 1984 20:30:40 Sony 2004 20 000 ans sous les verrous Warner Bros. -

Patriarchal-Industrial Anxiety and the Re- Turn of the Repressed (Eco-Critical) Simian Mon- Ster

PATRIARCHAL-INDUSTRIAL ANXIETY AND THE RE- TURN OF THE REPRESSED (ECO-CRITICAL) SIMIAN MON- STER David Christopher, University of Victoria Abstract Apocalyptic monkey monsters just keep coming back. Many of the stories have been subject to nu- merous remakes that date from the early-mid twentieth century, into the new millennium with myriad recurring visions of the simian monster, including Murders in the Rue Morgue (1917, 1932, 1986), King Kong (1933, 1976, 2005), Planet of the Apes (1968, 2001, 2011), and “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” (1963, 1983) to name just a few. And in the new millennium, Peter Jackson’s Kong (2005) participates in a rejuvenation of the giant mon- ster movie cycles. In Living in the End Times (2011), Slavoj Žižek states “one of the best ways to detect shifts in the ideological constellation is to compare consecutive remakes of the same story” (Žižek, End Times, 61). By doing so, and in conjunction with his articulation of the socio-psychological mechanics of fantasy, Žižek introduces an analytical framework through which to examine the intermittent return of the simian monster to popular cinema. As suggested here, the simian monster recurs not only because it is an effective uncanny receptacle for capitalist Othering, but also because it represents a larger patriarchal anxiety regarding the monstrous threat of nature and its conquest. Jackson’s Kong, for example, seems to have less to do with the atomic fear of the 1950s giant monster movie cycle with which it participates than with eco-disaster anxieties. Following the trajectory of both the films and their surrounding discourse, this article seeks to demonstrate that these films can be read as the evolution of nearly a century of eco-anxi- eties signified by cinematic simian monsters into increasingly explicit fantasies of redemption from the fear of ecological disaster that is embedded in the repressed contradictions of an aggressively industrial and patriarchal capitalist culture.