The Effectiveness of the Food and Beverage Industry's Self-Established

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Templar Newsletter

The Canadian Templar December 2015 Newsletter News and Report from our Grand Prior In this edition of the Canadian Templar you will find many articles and news items relating to recent world events. As an international Christian Order we all have been affected and will continue to be affected. Although it may appear to be a somber edition, the fact is that we can rejoice in our Faith, and know the Joy and the Truth, especially as we enter the Christmas season. Below is a message I sent to our Grand Commander Col Dr. Marcel de Picciotto, and Jean Pelegrin the Grand Prior of France, immediately following the horrible attacks in Paris. “Dear Grand Commander Marcel, Grand Prior Jean and all Brothers and Sisters in France, The Grand Priory of Canada and all the peoples of our nation send our sincere condolences for the senseless acts of cowardly barbarism that have taken place in Paris last night. No nation is immune from this horror. We must not be intimidated by terrorists and their inhumane actions. Canadians know this first hand and stand firmly Page 1 with our French Brothers and Sisters at this dark and difficult time. Our thoughts and Prayers are with you all.” As many of you know, on November 6 we lost a dear friend, a dedicated and faithful member of our Order, former Grand Commander Major General Robert Disney. Both Robert and his lovely wife Sheila have been to Canada many times. He was installed as Grand Commander at the Toronto international gathering and considered Canadians among his second family. -

A Big Screen Finish

The WEDNESDAY, APRIL 30, 2014 • VOL. 24, NO.24 $1.25 Congratulations SOVA Class of KLONDIKE 2013-2014! SUN A big screen finish Dawson's Kit Hepburn accepts the Made In The Yukon award from Dawson City International Short Film Festival director Dan Sokolowski. Read the festival wrap on page 10. Photo by Dan Davidson. in this Issue Spring's here 3 1,200 km 8 A lifetime award 7 Don’t forget, The Ice Bridge is officially closed. Caribou Legs is on the move. There is more to come from the Mother’s Day TH Heritage Department. is May 11th! What to see and do in Dawson! 2 Letters 5 We need your glasses! 8 Bookends 17 Letters 3 A reunion banquet 5 Rangers' report 9 Business Directory & Job Board 19 Uffish Thoughts 4 More Waste Water issues 6 TV Guide 13-16 City Notices 20 P2 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 30, 2014 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: SOVA SOVA STUDENT EXHIBITIONS: This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and At the SOVA Gallery & ODD Gallery, from April planning, so let us know in good time! To join this listing contact the office at 25 to May 14. SOVA Gallery will be open to the public for viewing from 9 to 1 p.m. [email protected]. ADMIN OFFICE HOURS Events Monday to Thursday or by appointment. DARK STRANGERS TOUR: JUSTIN RUTLEDGE, OH SUSANNA & KIM LIBRARY HOURS : Monday to Thursday, 8:30 a.m. -

St. Francis Desales TIL NOON TODAY! Everyone Annual St

UN Fabulous Finds Await St. Francis DeSales TIL NOON TODAY! Everyone Annual St. Francis DeSales Welcome! RUMMAGE SALE Catholic Church 345 Grand Avenue • Lebanon ONE DOLLAR LC RECORD SATURDAY AUGUST 24, 2019 VOL 2 ISSUE 23 LACLEDE COUNTY RECORD Local man drowns while ÀVKLQJDWULYHU KIRK PEARCE [email protected] A Lebanon man drowned while fishing at 12:55 p.m. Tuesday, a mile up the river from the Hull Ford Access on the Osage Fork of the Gasconade River. According to the Mis- souri State Highway Patrol, Benny G. Wilson, 62, was fishing from an elevated location, /&5SKRWR6WHYH6PLWK slipped and fell into U.S. Senator Roy Blunt, center, speaks at Lebanon’s Floyd W. Jones Airport Thursday surrounded by Ozarks Technical Community approximately 10 feet of *VSSLNLVMÄJPHSZ)S\U[[V\YLK[OLUL^6;*(]PH[PVUJSHZZMHJPSP[PLZH[[OLHPYWVY[ water and drowned. He was pronounced dead the scene by Laclede County Coroner Steve Murrell. Blunt tours OTC Aviation class 7KLVZDV7URRS,·V second drowning for STEVE SMITH Act was extended and they often dis- “We need to get more information to the month of August [email protected] cussed the shortage of aviation profes- people earlier about where jobs are and and the third for 2019. sionals, including pilots. try to connect people, even in high school, U.S. Senator Roy Blunt stopped by the “We need to think of new and innova- to something you’d like to do as early as Lebanon Airport Thursday to view the WLYHZD\VWRÀOOWKDWVKRUWDJHµKHVDLG´,W you can so you don’t have a lot of time OTC Lebanon Center Flight School. -

Sure Formula for Success Fremantlemedia's Tony Cohen

THE BUSINESS JOURNAL OF FILM, BROADCASTING, BROADBAND, PRODUCTION, DISTRIBUTION MARCH/APRIL 2011 VOL. 31 NO. 2 $9.75 In This Issue: MIP-Coming Serious Laughs L.A. Screenings ® NATPE’s Elevators www.videoage.org FremantleMedia’s Tony Cohen: Father & Daughter Teams: A Journalist With (Tele) Vision Sure Formula For Success BY BOB JENKINS BY DOM SERAFINI n a wide-ranging interview with VideoAge, FremantleMedia CEO Tony Cohen ranted, there are many more From France there were Gérard Oury reflected on his 32-year career, assessed what the future holds for the content father and son teams in the and Daniele Oury Thompson who industry and discussed how FremantleMedia has positioned itself to face what international entertainment collaborated on movies. Gérard died Cohen saw as a future that will be as exciting as it will be demanding. industry than there are father in 2006 at the age of 87, his daughter Cohen was appointed CEO when and daughter teams. Indeed, the London-based FremantleMedia we exhausted all (Continued on Page 36) was born in 2001. It was renamed after our resources IBritain’s Pearson Television sold its stakes just to come up with 24 of in RTL Group to Germany’s Bertelsmann. For Top Jobs In a Tough Mart Gsuch teams from 14 countries, A year earlier, Pearson Television had Execs Call On Top Job Finders merged with CLT-Ufa to create RTL and that was by including past Group. Pearson Television was created in players, such as Albert (Cubby) 1996, after the British media conglomerate and Barbara Broccoli. oward Lipson runs Lipson & Co. -

Canadian Humour

Canadian humour Canadian humour is an integral part of the Canadian Identity. There are several traditions in Canadian humour in both English and French. While these traditions are distinct and at times very different, there are common themes that relate to Canadians' shared history and geopolitical situation in North America and the world. Various trends can be noted in Canadian comedy. One thread is the portrayal of a "typical" Canadian family in an on-going radio or television series. Examples include La famille Plouffe, with its mix of drama, humour, politics and religion and sitcoms such as King of Kensington and La Petite Vie. Another major thread tends to be political and cultural satire: television shows such as CODCO, Royal Canadian Air Farce, La Fin du monde est à 7 heures and This Hour Has 22 Minutes, monologuists such as Yvon Deschamps and Rick Mercer and writers, including Michel Tremblay, Will Ferguson and Eric Nicol draw their inspiration from Canadian and Québécois society and politics. Another trend revels in absurdity, demonstrated by television series like The Kids in the Hall and The Frantics, and musician-comedians such as The Arrogant Worms, Three Dead Trolls in a Baggie and Bowser and Blue. Satire is arguably the primary characteristic of Canadian humour, evident in each of these threads, and uniting various genres and regional cultural differences. Humber College in Toronto and the École nationale de l'humour in Montreal offer post-secondary programmes in comedy writing and performance. Montreal is also home to the bilingual (English and French) Just For Laughs festival and to the Just for Laughs museum, a bilingual, international museum of comedy. -

Go Back in Time During Whitestone History Fair by SHELLEY HEFFERNAN 11 A.M.; Sunday, July 19, Linda Bennison Sarginison Will Lead in Worship at 9:30 A.M

16 - PARRY SOUND NORTH STAR • Wednesday, July 8, 2009 Go back in time during Whitestone history fair BY SHELLEY HEFFERNAN 11 a.m.; Sunday, July 19, Linda Bennison Sarginison will lead in worship at 9:30 a.m. Mike and Barb Biscaro and Kevin and News from in McKellar and 11 a.m. in Dunchurch; Ann (May) McMahon along with friends and Saturday, Aug. 1, there will be a yard sale/ family would like to say congratulations DUNCHURCH bake sale and barbecue at the Dunchurch to Melanie Biscaro and Tash May who United Church starting at 8 a.m. and running graduated from York University’s Bachelor of until noon. Nursing Program – both with honours! with lunch and prizes all for only $10. The Hagerman Ratepayers Association Everyone is very proud of them and Registration begins at 9:30 a.m. and play is holding its annual general meeting on they have both secured full-time nursing begins at 10 a.m. Saturday, July 11, at 10 a.m. at the United positions in the Barrie area. The next meat draw is Saturday, July 25, Church. The special guest speaker is Jai Melanie and Tash grew up together in at 4 p.m. followed by the legion’s famous Longhurst of the Aspen Valley Wildlife Dunchurch and Tash is engaged to young horse races. One of my favourite events Sanctuary. The next general meeting is Michael Biscaro (Melanie’s twin) and both is coming up: the legion’s annual fish fry Aug. 13 at the legion in Dunchurch, and have been a great support to each other is Saturday, Aug. -

Sweeping Changes Proposed for Immigration to Finland

ISSUE 18 (50) • 9 – 15 MAY 2008 • €3 • WWW.HELSINKITIMES.FI DOMESTIC NEWS BUSINESS LIFESTYLE CULTURE EAT&DRINK Focus Aviation Diplomats’ Ellen Thesleff It’s on waste harmed by life in in Retretti’s brunch prevention expensive fuel Finland summer time! page 4 page 12 page 18 page 21 page 22 LEHTIKUVA / HEIKKI SAUKKOMAA An aging employee needs work and rest in a suitable relation TERHI LEINIÖ – STT pervisors and continuous adminis- MICHAEL NAGLER – HT trative changes decreased the work satisfaction of the elderly. EVEN a few extra free days would Maija-Kaarina Saloranta, 73, help the elderly to cope with their has remained eager to work even work. Most of the respondents in a during retirement. “I work because recent survey by the Rehabilitation it’s fun. Working also provides you Foundation and the UKK Institute with a routine and brings vigour to do not necessarily want semi-re- your everyday life. Otherwise life tirement. Instead they want a slack- would be just reading Helsingin Sa- ening in work schedules. nomat,” she sums up. Rehabilitation Foundation senior Saloranta, who lives in Helsin- researcher Tiina Pensola’s proposed ki, retired at 65 from Yleisradio in age-related free time could be a pre- 2000 but she still participates in the ventive measure with which more publishing of an organisation mag- people could keep on working long- azine and her voice can be heard in er without fatigue and burnout. commercials and in the voice books “Age-related free time would be of the Finnish Federation of the Vis- more affordable for the employer, ually Impaired. -

Finland Mourns Hyvinkää Shooting Victims

ISSUE 22 (253) • 31 MAY – 6 JUNE 2012 • €3 • WWW.HELSINKITIMES.FI BUSINESS Hyvinkää, two of whom were killed and seven injured. Telia- Chairman of the Finnish Central Nokia news Association for Mental Health Pek- With the mobile phone giant re- ka Sauri points out that centralised portedly in dire straits, we an- storage of fi rearms would make alyse some of the rumours cur- Sonera acts such as that in Hyvinkää less rently circulating about its future. likely to occur.“The best way by far See page 8 to prevent these kinds of acts is to spying LEHTIKUVA / HEIKKI SAUKKOMAA limit the availability of fi rearms and to supervise their storage,” Sau- ri says. He believes the Hyvinkää FESTIVAL SPECIAL shooting proves that gun control scandal laws are still far from adequate. Minister of the Interior Päivi Members of the public leave tributes to those killed and injured in the Räsänen (Christian Democrats) says Finnish-Swedish commu- Hyvinkää shooting. there were very few signs in advance that the Hyvinkää shooting would nications company in hot take place. This would have made it water over surveillance very diffi cult to prevent. Räsänen also said on the television programme A- equipment. Finland mourns Studio that the risk of these kinds of events could be reduced if the distress of young people could be relieved. Festival fever DAVID DUNNE Public health administration ex- Whether you prefer metal or Mo- HELSINKI TIMES Hyvinkää pert at the University of Tampere zart, there will be plenty of op- Matti Rimpelä, who was also in- portunities to get your groove on TELEPHONE company and mobile terviewed on the programme, in this summer. -

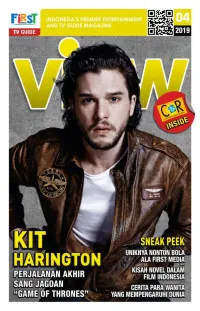

View 201904.Pdf

MY TOP 10 THE WILD CANADIAN YEAR ANIMAL PLANET Film dokumenter tentang satwa liar yang berada di Kanada yang hidup dalam cuaca ekstrim. Dalam MY kondisi tersebut, seorang fotografer mengambil momen penting tentang kehidupan satwa dan cara mereka berinteraksi dengan satwa TOP lainnya, serta bertahan hidup dari kondisi ekstrim. Hal itu menjadikan setiap shoot dari bidikan kamera fotografer begitu berharga. SINGLE PARENTS FOXLIFE Menceritakan beberapa orang tua tunggal yang saling membantu satu sama lain dalam membesarkan anak- anak mereka yang 10FAVORITE berusia 7 tahun. Namun terjadi hubungan pribadi PROGRAMS antara orang tua mereka. LADY CHADalrae’s LOVER ANT-MAN AND THE WASP ONE FOX MOVIES Menceritakan Saat Ant Man tentang tiga wanita berusaha berjuang paruh baya, Cha Jin untuk kembali dengan Ok (Ha Hee Ra), Oh kehidupannya, Dal Sook (Ahn Sun dengan tanggung Young) dan Nam jawabnya sebagai Mi Rae (Go Eun orang tua, dia Mi). Mereka adalah berhadapan kembali teman sekolah dengan Hope menengah yang van Dyne dan Dr. percaya bahwa Hank Pym yang mereka menjalani mendesaknya dengan misi baru. Scott kembali hidup bahagia, tetapi mereka menghadapi bertarung di samping The Wasp. Mereka pun akan krisis dalam hidup mereka. bekerja sama dalam misi baru tersebut. 4 MY TOP 10 HOTEL SOUL GOOD BLOWING UP HISTORY CELESTIAL MOVIES DISCOVERY CHANNEL Katie (Chrissie Mengungkap Chau) adalah rahasia bangunan eksekutif senior bersejarah ataupun di hotel bintang yang menjadi lima. Tetapi suatu landmark di daerah hari, sahabatnya tersebut. Mulai dari mengkhianatinya ukuran, skala, umur, dan mencuri dan lokasi serta pekerjaan serta keajaiban kuno pacarnya. Lebih seperti Piramida buruk lagi, Katie di Mesir hingga terkena pecahan keajaiban modern di Manhattan seperti Empire hujan meteor dan setelah sadar kembali, ia State Building. -

Canadian Claimants Group (CCG)

WRITTEN DIRECT TESTIMONY OF JANICE DE FREITAS (CBC - RIGHTS ADMINISTRATION) 2004—2005 Cable Royalty Distribution Proceeding Docket No. 2007-03 CRB CD 2004-2005 1. Introduction I am Manager of Rights Administration for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation/Radio-Canada (CBC/Radio-Canada) at the Head Office in Ottawa. I have worked for the CBC since 1980. For the last 15 years, I have served as Chairman of the Canadian Claimants Group (CCG). Before assuming my current position, I spent nine years in CBC’s television program distribution department eventually managing the Educational Sales unit. Those responsibilities called for me to be familiar with the English television network’s programming, and rights administration. CBC/Radio-Canada is Canada’s national public broadcaster, and one of its largest and most important cultural institutions. It was created by an Act of Parliament in 1936, beginning with Radio. Bilingual television services were launched in 1952. CBC/Radio-Canada is licensed and regulated by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC)1. CBC/Radio-Canada employs approximately 9,930 Canadians in 27 regional offices across the country. CBC programming is provided on multiple platforms: television (both traditional over-the-air and cable networks), radio, the Internet, satellite radio, digital audio and a recording label. Through this array of activities, CBC/Radio-Canada delivers content in English, French, and eight aboriginal languages. In addition to this, programming is available in seven other languages including Spanish, Russian and Mandarin on both Radio Canada International, and Web-based www.rciviva.ca, a radio service for recent and aspiring immigrants to Canada. -

Muhammad Afzal Upal Moderate Fundamentalists

Muhammad Afzal Upal Moderate Fundamentalists Muhammad Afzal Upal Moderate Max Mustermann FundamentalistsFunktion der Darstellung The Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama’at in the Lens of Cognitive Science of Religion Unterscheidung als Hilfs- und Orientierungsbegriff zur Dekodierung ManagingHerausgegeben Editor: von Katarzyna Tempczyk Max Mustermann Associate Editor: Rasa Pranskevičiūtė Language Editor: Wayne Smith Journal xyz 2017; 1 (2): 122–135 The First Decade (1964-1972) Research Article Max Musterman, Paul Placeholder What Is So Different About Neuroenhancement? Was ist so anders am Neuroenhancement? Pharmacological and Mental Self-transformation in Ethic Comparison Pharmakologische und mentale Selbstveränderung im ethischen Vergleich https://doi.org/10.1515/xyz-2017-0010 received February 9, 2013; accepted March 25, 2013; published online July 12, 2014 Abstract: In the concept of the aesthetic formation of knowledge and its as soon as possible and success-oriented application, insights and profits without the reference to the arguments developed around 1900. The main investigation also includes the period between the entry into force and the presentation in its current version. Their function as part of the literary portrayal and narrative technique. Keywords: Function, transmission, investigation, principal, period Dedicated to Paul Placeholder 1 Studies and Investigations The main investigation also includes the period between the entry into force and the presentation in its current version. Their function as part of the literary por- trayal and narrative technique. *Max Musterman: Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, 2 Pei-Ning Road Keelung 20224, Taiwan (R.O.C), e-mail: [email protected] Paul Placeholder: Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, 2 Pei-Ning ISBN: 978-3-11-055648-3 Road Keelung 20224, Taiwan (R.O.C), e-mail: [email protected] e-ISBN: 978-3-11-055664-3 Open Access. -

Annexe 3 Émissions D'intérêt National Aux Heures De

ANNEXE 3 ÉMISSIONS D’INTÉRÊT NATIONAL AUX HEURES DE GRANDE ÉCOUTE ANNEXE 3 - ÉMISSIONS D'INTÉRÊT NATIONAL (EIN) EN HEURE DE GRANDE ÉCOUTE Condition de licence 25(a) - Année de diffusioin 2019-2020 CBC ENGLISH TELEVISION Langue de Production Titre de l'émission Catégorie d'émmission Heures Producteur/Adresse Indép. ou interne Régions production CLOSM 9/11 Kids 02B-Documentaires de longue durée Anglais 2.0 Saloon Media Inc. 411 Richmond Street East Suite #100 Toronto, ON M5A 3S5 Indépendante Ontario Non Absolutely Canadian - Leslie McCurdy Story: On the Money 02B-Documentaires de longue durée Anglais 1.0 CANADIAN ARTS PRODUCTIONS 819 Windermere Road Windsor Ontario N8Y 3E3 Indépendante Ontario Non Absolutely Toronto - 2018/19 - 2019 Toronto Docs (2019). 02B-Documentaires de longue durée Anglais 1.0 CBC Network Interne Multi Non 07C-Émissions spéciales, mini-séries et Across the Line (Feature Film) Anglais 1.0 DHX-Cole Harbour Productions Inc. 1478 Queen Street Halifax Nonva Scotia B3J 2H7 Indépendante Atlantique Non longs métrages pour la télévision A Kandahar Away 02B-Documentaires de longue durée Anglais 2.0 Kitab Productions Inc. 4-1146 College Street Toronto, Ontario Canada M6H 1B6 Indépendante Ontario Non A Merry Murdoch Christmas (2015) 07A-Séries dramatiques en cours Anglais 2.0 Shaftesbury Murdoch IX Inc. 163 Queen Street East, Suite 100 Toronto Ontario M5A 1S1 Indépendante Ontario Non Anne with an E - 2-08 - Struggling Against the Perception of Facts 07A-Séries dramatiques en cours Anglais 1.0 Nonrthwood Anne Duo Inc. 74 Langley Avenue Toronto Ontario M4K 1B5 Indépendante Ontario Non Anne with an E - 2-09 - What We Have Been Makes Us What We Are 07A-Séries dramatiques en cours Anglais 1.0 Nonrthwood Anne Duo Inc.