By Tom Ilifje, Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France)

diversity Article The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France) Arnaud Faille 1,* and Louis Deharveng 2 1 Department of Entomology, State Museum of Natural History, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany 2 Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), UMR7205, CNRS, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 75005 Paris, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Located in Northern Pyrenees, in the Arbas massif, France, the system of the Coume Ouarnède, also known as Réseau Félix Trombe—Henne Morte, is the longest and the most complex cave system of France. The system, developed in massive Mesozoic limestone, has two distinct resur- gences. Despite relatively limited sampling, its subterranean fauna is rich, composed of a number of local endemics, terrestrial as well as aquatic, including two remarkable relictual species, Arbasus cae- cus (Simon, 1911) and Tritomurus falcifer Cassagnau, 1958. With 38 stygobiotic and troglobiotic species recorded so far, the Coume Ouarnède system is the second richest subterranean hotspot in France and the first one in Pyrenees. This species richness is, however, expected to increase because several taxonomic groups, like Ostracoda, as well as important subterranean habitats, like MSS (“Milieu Souterrain Superficiel”), have not been considered so far in inventories. Similar levels of subterranean biodiversity are expected to occur in less-sampled karsts of central and western Pyrenees. Keywords: troglobionts; stygobionts; cave fauna Citation: Faille, A.; Deharveng, L. The Coume Ouarnède System, a Hotspot of Subterranean Biodiversity in Pyrenees (France). Diversity 2021, 1. Introduction 13 , 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ Stretching at the border between France and Spain, the Pyrenees are known as one d13090419 of the subterranean hotspots of the world [1]. -

Underwater Speleology Journal of the Cave Diving Section of the National Speleological Society

Underwater Speleology Journal of the Cave Diving Section of the National Speleological Society INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Possible Explanations For The Lack Of Formations In Underwater Caves In FLA The Challenge At Challenge Cave Diving Science Visit with A Cave: Cannonball Cow Springs Clean Up Volume 41 Number 1 January/February/March 2014 Underwater Speleology NSS-CDS Volume 41 Number 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS January/February/March 2014 CHAIRMAN contents Joe Citelli (954) 646-5446 [email protected] Featured Articles VICE CHAIRMAN Tony Flaris (904) 210-4550 Possible Explanations For The Lack Of Formations In Underwater Caves In FLA [email protected] By Dr. Jason Gulley and Dr. Jason Polk............................................................................6 TREASURER The Challenge At Challenge Terri Simpson By Jim Wyatt.................................................................................................................8 (954) 275-9787 [email protected] Cave Diving Science SECRETARY By Peter Buzzacott..........................................................................................................10 TJ Muller Visit With A Cave: Cannonball [email protected] By Doug Rorex.................................................................................................................16 PROGRAM DIRECTORS Book Review: Classic Darksite Diving: Cave Diving Sites of Britain and Europe David Jones By Bill Mixon..............................................................................................................24 -

Modern-Day Explorers

UT] O B A THINK O MODERN-DAY EXPLORERS Who are the men and women who are conquering the unthinkable? They walk among us, seemingly normal, but undertake feats of extreme adventure and live to tell the tale… METHING T SO Alex Honnold famous free soloist [ LEWIS PUGH RHYMES with “whew” “...he couldn’t feel his fingertips for CROSSROADS four months!” The funniest line in Lewis Pugh’s recently-released memoir, 21 Yaks and a Speedo: How to achieve your impossible (Jonathan Ball Publishers) is when he says, “I’m not a rule-breaker by nature.” The British-South African SAS reservist and endurance swimmer is a regular in the icy waters of the Arctic and Antarctic ALEX HONNOLD oceans. He’s swum long-distance in every ocean in the world and GIVES ROCKS By Margot Bertelsmann holds several world records, perhaps most notably the record of being the first person to swim 500 metres freestyle in the Finnish World Winter Swimming Championships (the usual distance is 25 “...if you fall, you’ll likely die (and metres breaststroke) – wearing only a Speedo. He also swam a near-unimaginable 1000 metres in -1.7°C waters near the North many free soloists have).” Pole, after which he couldn’t feel his fingertips for four months! When he’s not breaking endurance records, Lewis tours the When your appetite for the thrill of danger is as large as globe speaking about his passion: conserving our oceans and 27-year-old Alex Honnold’s, you’d better find a 600 metres- water, climate change and global warming. -

Karst Development Mechanism and Characteristics Based on Comprehensive Exploration Along Jinan Metro, China

sustainability Article Karst Development Mechanism and Characteristics Based on Comprehensive Exploration along Jinan Metro, China Shangqu Sun 1,2, Liping Li 1,2,*, Jing Wang 1,2, Shaoshuai Shi 1,2 , Shuguang Song 3, Zhongdong Fang 1,2, Xingzhi Ba 1,2 and Hao Jin 1,2 1 Research Center of Geotechnical and Structural Engineering, Shandong University, Jinan 250061, China; [email protected] (S.Sun); [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (S.Shi); [email protected] (Z.F.); [email protected] (X.B.); [email protected] (H.J.) 2 School of Qilu Transportation, Shandong University, Jinan 250061, China 3 School of Transportation Engineering, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan 250101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 August 2018; Accepted: 19 September 2018; Published: 21 September 2018 Abstract: Jinan is the capital of Shandong Province and is famous for its spring water. Water conservation has become the consensus of Jinan citizens and the government and the community. The construction of metro engineering in Jinan has lagged behind other cities of the same scale for a long time. The key issue is the protection of spring water. When metro lines are constructed in Jinan karst area, the water-inrushing, quicksand, and piping hazards can easily occur, which can change the groundwater seepage environment and reduce spring discharge. Therefore, we try to reveal the development conditions, mechanism, and mode of karst area in Jinan. In addition, we propose the comprehensive optimizing method of “shallow-deep” and “region-target” suitable for exploration of karst areas along Jinan metro, and systematically study the development characteristics of the karst areas along Jinan metro, thus providing the basis for the shield tunnel to go through karst areas safely and protecting the springs in Jinan. -

DRAFT 8/8/2013 Updates at Chapter 40 -- Karstology

Chapter 40 -- Karstology Characterizing the mechanism of cavern accretion as "force" tends to suggest catastrophic attack, not a process of subtle persistence. Publicity for Ohio's Olentangy Indian Caverns illustrates the misconception. Formed millions of years ago by the tremendous force of an underground river cutting through solid limestone rock, the Olentangy Indian Caverns. There was no tremendous event millions of years ago; it's been dissolution at a rate barely discernable, century to century. Another rendition of karst stages, this time in elevation, as opposed to cross-section. Juvenile Youthful Mature Complex Extreme 594 DRAFT 8/8/2013 Updates at http://www.unm.edu/~rheggen/UndergroundRivers.html Chapter 40 -- Karstology It may not be the water, per se, but its withdrawal that initiates catastrophic change in conduit cross-section. The figure illustrates stress lines around natural cavities in limestone. Left: Distribution around water-filled void below water table Right: Distribution around air-filled void after lowering water table. Natural Bridges and Tunnels Natural bridges begin as subterranean conduits, but subsequent collapse has left only a remnant of the original roof. "Men have risked their lives trying to locate the meanderings of this stream, but have been unsuccessful." Virginia's Natural Bridge, 65 meters above today's creek bed. George Washington is said to have surveyed Natural Bridge, though he made no mention it in his journals. More certain is that Thomas Jefferson purchased "the most sublime of nature's works," in his words, from King George III. Herman Melville alluded to the formation in describing Moby Dick, But soon the fore part of him slowly rose from the water; for an instant his whole marbleized body formed a high arch, like Virginia's Natural Bridge. -

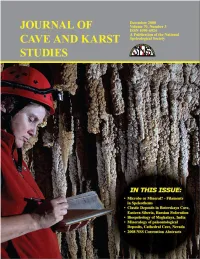

Complete Issue

EDITORIAL EDITORIAL Indexing the Journal of Cave and Karst Studies: The beginning, the ending, and the digital era IRA D. SASOWSKY Dept. of Geology and Environmental Science, University of Akron, Akron, OH 44325-4101, tel: (330) 972-5389, email: [email protected] In 1984 I was a new graduate student in geology at Penn NSS. The effort took about 2,000 hours, and was State. I had been a caver and an NSS member for years, published in 1986 by the NSS. and I wanted to study karst. The only cave geology course I With the encouragement of Editor Andrew Flurkey I had taken was a 1-week event taught by Art Palmer at regularly compiled an annual index that was included in Mammoth Cave. I knew that I had to familiarize myself the final issue for each volume starting in 1987. The with the literature in order to do my thesis, and that the Bulletin went through name changes, and is currently the NSS Bulletin was the major outlet for cave and karst Journal of Cave and Karst Studies (Table 1). In 1988 I related papers (Table 1). So, in order to ‘‘get up to speed’’ I began using a custom-designed entry program called SDI- undertook to read every issue of the NSS Bulletin, from the Soft, written by Keith Wheeland, which later became his personal library of my advisor, Will White, starting with comprehensive software package KWIX. A 5-year compi- volume 1 (1940). When I got through volume 3, I realized lation index (volumes 46–50) was issued by the NSS in that, although I was absorbing a lot of the material, it 1991. -

Self-Driving Cars Deep-Sea Diving Mosquito Control Visionaries

SUMMER 2020 ve ions CVisionariesreat navigating theDire intersectioni of art and commercect PLUS Self-Driving Cars Deep-Sea Diving Mosquito Control On June 11, President Rhonda Lenton sent the communication • Deepening the integration of critical race theory and anti-racism forms of discrimination. I also know that these actions cannot be SPECIAL MESSAGE below to students, faculty and staff, announcing a series of steps that the University is taking as part of York’s shared responsibility training into our curriculum through, for example, requirements top-down. York needs to listen carefully to those living with anti- FROM THE PRESIDENT to build a more inclusive, diverse and just community. in student learning outcomes, and the potential creation of a new Black racism to shape programs that respond to their needs and to micro-credential in anti-racism and anti-bias training available identify new initiatives that will ensure that every member of our community is supported as they pursue their personal visions of OLLOWING the global WHAT WE ARE DOING NOW to all members of the York community using digital badging. educational, research and career success. outpouring of grief, More recently, York has been working to increase the represen- • Working with Black students, faculty and staff to refine our com- To that end, we will be engaging in a series of consultations with anger and demands for tation of Black faculty and ensure diverse applicant pools in our munity safety model. F Black students, faculty and staff over the coming weeks. We are change following the complement searches. I am pleased to highlight that York has hired We hope that these actions represent a substantive first step in finalizing the details of this consultation process, and I hope to brutal death of George Floyd in 14 new Black faculty members over the past two years, under- fulfilling our responsibility to address anti-Black racism and all provide the community with more information soon. -

Chasing Dreams, Near Far – Wherever They Are… Renata Rojas and Her Quest for Her Titanic!

Chasing Dreams, Near Far – Wherever They Are… Renata Rojas and Her Quest for Her Titanic! Gary Lehman Renata Rojas is the former president of NYC’s venerable scuba dive club The New York City Sea Gypsies™, and banking executive, as well as member of NYC’s Explorers Club. She is also one of the mission specialists aboard submersible research vessel Titan, which will be diving on and documenting RMS Titanic in July 2018. Titan was built by Oceangate, a company based in Everett, Washington. Oceangate builds submersibles for undersea industrial, scientific, environmental, military and historical/exploration missions. Oceangate’s objective in diving their submersible to Titanic is to create an accurate and immensely-detailed 2018 baseline engineering model of the current structure of Titanic, using state-of-the-art photoprogrammetry and laser beam measurement capabilities. Titanic has been on the bottom in 12,500 feet since it sank in April 1912, about 300 miles southeast of Newfoundland. RMS Titanic Today The wreck was located in 1985 by a joint American–French Expedition led by oceanographers Dr. Bob Ballard (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute) and Jean-Louis Michel (L’Institut Français de Recherche pour l ‘Exploitation de la Mer) in collaboration with the US Navy. The wreck has been inspected and photographed many times by personnel aboard submersibles and by remote-operated vehicles (ROV’s) since the wreck’s location. There is damage on the wreck, resulting from submersible landings on it. Artifacts have been removed from the site. The structure is degrading due to corrosion and biological processes, which are deteriorating the ship’s iron. -

2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Puerto-Princesa Subterranean River National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2017 (archived) Finalised on 09 November 2017 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Puerto-Princesa Subterranean River National Park. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Puerto-Princesa Subterranean River National Park SITE INFORMATION Country: Philippines Inscribed in: 1999 Criteria: (vii) (x) Site description: This park features a spectacular limestone karst landscape with an underground river. One of the river's distinguishing features is that it emerges directly into the sea, and its lower portion is subject to tidal influences. The area also represents a significant habitat for biodiversity conservation. The site contains a full 'mountain- to-sea' ecosystem and has some of the most important forests in Asia. © UNESCO IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Puerto-Princesa Subterranean River National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) SUMMARY 2017 Conservation Outlook Good with some concerns The spectacular cave system of the site and the natural phenomena of the interface between the sea and the underground river are well preserved although experiencing increasing impacts from the increase in visitors and tourism developments. Some degradation of the site’s biodiversity values by exploitation by the local community is recognized but the extent of the impacts of these threats is unknown given the lack of monitoring data and research. The protection and effective management of the property is hampered by a complex legal framework and some confusion as to what is actually the World Heritage property, and the donation of land areas within its boundaries to accommodate the residents. -

Living in a Cave

o c e a n Bermuda Deepwater Caves: Dive of Discovery Expl ration & Research Living in a Cave Focus Life in anchialine and marine caves Grade Level 7-8 (Biology,English/Language Arts [Technical Reading]) Focus Question What kinds of habitats are found in anchialine caves, and what adaptations are seen in organisms that live in these habitats? Learning Objectives n Students will compare and contrast anchialine and marine caves. n Students will describe the biological significance of animals that live in anchialine and marine caves. n Students will explain why it is important to protect individual caves from destruction or pollution. n Students will describe some of the precautions that scientists must take when studying these caves. Materials q Copies of Save the Cave! Student Guide, one copy for each student group Audio-Visual Materials q (Optional) Interactive white board, computer projector or other equipment for showing images of underwater caves Teaching Time One or two 45-minute class periods Seating Arrangement Groups of two to four students Maximum Number of Students Image captions/credits on Page 2. 32 1 www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov Bermuda Deepwater Caves 2011: Dive of Discovery Grades 7-8 (Biology/English Language Arts [Technical Reading]) Key Words Anchialine Cave Stygobite Conservation Multibeam sonar Background Information NOTE: Explanations and procedures in this lesson are written at a level appropriate to professional educators. In presenting and discussing this material with students, educators may need to adapt the language and instructional approach to styles that are best suited to specific student groups. Anchialine caves are partially or totally submerged caves that are located within a few kilometers inland from coastal areas. -

Kavieng • Papua New Guinea Evolution CCR Rebreather Piracy

Kavieng • Papua New Guinea Evolution CCR Rebreather Piracy • Dominican Republic The Ghosts of Sunda Strait • Java Sea Blue Holes of Abaco • Bahamas Operation Hailstorm • Chuuk Lingcod • Pacific Northwest Selah Chamberlain • Lake Michigan Diving Northern Sulawesi • Indonesia Photography by Thaddius Bedford UNEXSO • Grand Bahama Customized CCR Systems The only multi-mission, multi-tasking CCR in the world. Features: • Customized electronics and decompression systems • Custom CO2 scrubber assemblies • Custom breathing loop and counterlung systems • Modularized sub systems • Highly suitable for travel • Suitable for Science, commercial, and recreational diving www.customrebreathers.com Ph: 360-330-9018 [email protected] When only the highest quality counts… Double Cylinder Bands Stage Cylinder Bands Technical Harness Hardware Accessory Dive Hardware ADDMM Features ISSUE 23 8 Where Currents Collide 8 KAVIENG Papua New Guinea Text and Photography by Peter Pinnock 14 Evolution CCR 8 Text by Cass Lawson 31 31 19 Dominican Republic Rebreather Piracy Silent Attack to Land and Sea Text by Curt Bowen • Photography by Jill Heinerth and Curt Bowen 14 26 The Ghosts of Sunda Strait The Wrecks of USS Houston and HMAS Perth Text and Photography by Kevin Denlay Exploring the 31 Blue Holes of Abaco 19 with the Bahamas Underground Text and Photography by Curt Bowen 39 Operation Hailstorm CCR Invasion • Truk Lagoon 75 Text and Photography by Curt Bowen 55 LINGCOD Queen of Northwest Predators 65 Text and Photography by John Rawlings 19 59 Wreck of the -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Matthew Doyle (530) 238-2341

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Matthew Doyle (530) 238-2341 LAKE SHASTA CAVERNS TO CELEBRATE INTERNATIONAL DAY OF CAVES AND SUBTERRANEAN WORLD ON 6 JUNE. Cave Enthusiasts Across the Globe Bring Attention to the Importance of our Subterranean World. LAKEHEAD, CA USA (6 June 2019) — Lake Shasta Caverns National Natural Landmark, a member of the International Show Caves Association, joins cave enthusiasts around the world to increase awareness about the importance of caves and karst landscapes by celebrating International Day of Caves & the Subterranean World. “Caves and karst landscapes are places of wonder and majestic beauty. We see the recognition of the importance of our subterranean world increasing worldwide,” said Brad Wuest, president of the International Show Caves Association, and president, owner and operator of Natural Bridge Caverns, Texas, USA. “Show caves worldwide are embracing their role of protecting and preserving caves and providing a place for people to learn about these special natural, cultural and historical resources. Show caves also play an important role in nature tourism and sustainable development, providing jobs and helping the economy of their regions. Approximately 150 million people visit show caves each year, learning about our subterranean world” said Wuest. Caves and karst make landscapes diverse, fascinating, and rich in resources, including the largest springs and most productive groundwater on Earth, not to mention at least 175 different minerals, a few of which have only been found in caves. These landscapes provide a unique subsurface habitat for both common and rare animals and preserve fragile archaeological and paleontological materials for future generations. “Everyone is touched by caves and karst.