Metrics to Avoid – the Journal Impact Factor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Relation Between the Wos Impact Factor, the Eigenfactor, the Scimago Journal Rank, the Article Influence Score and the Journal H-Index

1 On the relation between the WoS impact factor, the Eigenfactor, the SCImago Journal Rank, the Article Influence Score and the journal h-index Ronald ROUSSEAU 1 and the STIMULATE 8 GROUP 2 1 KHBO, Dept. Industrial Sciences and Technology, Oostende, Belgium [email protected] 2Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Brussels, Belgium The STIMULATE 8 Group consists of: Anne Sylvia ACHOM (Uganda), Helen Hagos BERHE (Ethiopia), Sangeeta Namdev DHAMDHERE (India), Alicia ESGUERRA (The Philippines), Nguyen Thi Ngoc HOAN (Vietnam), John KIYAGA (Uganda), Sheldon Miti MAPONGA (Zimbabwe), Yohannis MARTÍ- LAHERA (Cuba), Kelefa Tende MWANTIMWA (Tanzania), Marlon G. OMPOC (The Philippines), A.I.M. Jakaria RAHMAN (Bangladesh), Bahiru Shifaw YIMER (Ethiopia). Abstract Four alternatives to the journal Impact Factor (IF) indicator are compared to find out their similarities. Together with the IF, the SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), the EigenfactorTM score, the Article InfluenceTM score and the journal h- index of 77 journals from more than ten fields were collected. Results show that although those indicators are calculated with different methods and even use different databases, they are strongly correlated with the WoS IF and among each other. These findings corroborate results published by several colleagues and show the feasibility of using free alternatives to the Web of Science for evaluating scientific journals. Keywords: WoS impact factor, Eigenfactor, SCImago Journal Rank (SJR), Article Influence Score, journal h-index, correlations Introduction STIMULATE stands for Scientific and Technological Information Management in Universities and Libraries: an Active Training Environment. It is an international training programme in information management, supported by the Flemish Interuniversity Council (VLIR), aiming at young scientists and professionals from 2 developing countries. -

Amplifying the Impact of Open Access: Wikipedia and the Diffusion of Science

(forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology) Amplifying the Impact of Open Access: Wikipedia and the Diffusion of Science Misha Teplitskiy Grace Lu Eamon Duede Dept. of Sociology and KnowledgeLab Computation Institute and KnowledgeLab University of Chicago KnowledgeLab University of Chicago [email protected] University of Chicago [email protected] (773) 834-4787 [email protected] (773) 834-4787 5735 South Ellis Avenue (773) 834-4787 5735 South Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 5735 South Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Chicago, Illinois 60637 Abstract With the rise of Wikipedia as a first-stop source for scientific knowledge, it is important to compare its representation of that knowledge to that of the academic literature. Here we identify the 250 most heavi- ly used journals in each of 26 research fields (4,721 journals, 19.4M articles in total) indexed by the Scopus database, and test whether topic, academic status, and accessibility make articles from these journals more or less likely to be referenced on Wikipedia. We find that a journal’s academic status (im- pact factor) and accessibility (open access policy) both strongly increase the probability of its being ref- erenced on Wikipedia. Controlling for field and impact factor, the odds that an open access journal is referenced on the English Wikipedia are 47% higher compared to paywall journals. One of the implica- tions of this study is that a major consequence of open access policies is to significantly amplify the dif- fusion of science, through an intermediary like Wikipedia, to a broad audience. Word count: 7894 Introduction Wikipedia, one of the most visited websites in the world1, has become a destination for information of all kinds, including information about science (Heilman & West, 2015; Laurent & Vickers, 2009; Okoli, Mehdi, Mesgari, Nielsen, & Lanamäki, 2014; Spoerri, 2007). -

Ranking Forestry Journals Using the H-Index

Ranking forestry journals using the h-index Journal of Informetrics, in press Jerome K Vanclay Southern Cross University PO Box 157, Lismore NSW 2480, Australia [email protected] Abstract An expert ranking of forestry journals was compared with journal impact factors and h -indices computed from the ISI Web of Science and internet-based data. Citations reported by Google Scholar offer an efficient way to rank all journals objectively, in a manner consistent with other indicators. This h-index exhibited a high correlation with the journal impact factor (r=0.92), but is not confined to journals selected by any particular commercial provider. A ranking of 180 forestry journals is presented, on the basis of this index. Keywords : Hirsch index, Research quality framework, Journal impact factor, journal ranking, forestry Introduction The Thomson Scientific (TS) Journal Impact Factor (JIF; Garfield, 1955) has been the dominant measure of journal impact, and is often used to rank journals and gauge relative importance, despite several recognised limitations (Hecht et al., 1998; Moed et al., 1999; van Leeuwen et al., 1999; Saha et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2005; Moed, 2005; Dellavalle et al., 2007). Other providers offer alternative journal rankings (e.g., Lim et al., 2007), but most deal with a small subset of the literature in any discipline. Hirsch’s h-index (Hirsch, 2005; van Raan, 2006; Bornmann & Daniel, 2007a) has been suggested as an alternative that is reliable, robust and easily computed (Braun et al., 2006; Chapron and Husté, 2006; Olden, 2007; Rousseau, 2007; Schubert and Glänzel, 2007; Vanclay, 2007; 2008). -

Impact Factors Can Mislead Was 'Valid' Or Not

going to determine whether one's research Impact factors can mislead was 'valid' or not. Research productivity is now evaluated by a National Committee SIR - Impact factors (IFs) for scientific purchased from ISL In each category we selected by the Spanish Science and journals, developed by the Institute for compared the ranking of journals by IF as Education Ministry, which simply rates Scientific Information (ISi) and published printed in the JCR to the one based on our one's research according to the number of in the section "Journals per category, correct IF, by calculating the number of SCI publications accumulated over a six ranked by Impact Factor" of the Journal journals moving at least 1, 3, 5 or 10 posi year period. Citation Reports (JCR), are frequently used tions. The table shows the five categories This may work in some fields, but it fails to evaluate the status of scientific journals affected most severely, measured through in botany, geology and zoology, for exam or even the publication output of scientists. the percentage of journals moving at least ple, because these disciplines do not gener The IF of a journal in year T is defined as one position in the ranking. The categories ate as many articles or citations as, say, the number of citations in year T to docu- listed relate not only to the medical sciences biotechnology or genetics. The combination ments published in that journal in years but also to chemistry and engineering of less frequent citations and a publishing T - 1 and T- 2 , divided by the number of sciences. -

Introduction to Bibliometrics

Introduction to Bibliometrics Bibliometrics A new service of the university library to support academic research Carolin Ahnert and Martin Bauschmann This work is licensed under: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Chemnitz ∙ 16.05.17 ∙ Carolin Ahnert, Martin Bauschmann www.tu-chemnitz.de Introduction to Bibliometrics What is bibliometrics? – short definition „Bibliometrics is the statistical analysis of bibliographic data, commonly focusing on citation analysis of research outputs and publications, i.e. how many times research outputs and publications are being cited“ (University of Leeds, 2014) Quantitative analysis and visualisation of scientific research output based on publication and citation data Chemnitz ∙ 16.05.17 ∙ Carolin Ahnert, Martin Bauschmann www.tu-chemnitz.de Introduction to Bibliometrics What is bibliometrics? – a general classification descriptive bibliometrics evaluative bibliometrics Identification of relevant research topics Evaluation of research performance cognition or thematic trends (groups of researchers, institutes, Identification of key actors universities, countries) interests Exploration of cooperation patterns and Assessment of publication venues communication structures (especially journals) Interdisciplinarity Productivity → visibility → impact → Internationality quality? examined Topical cluster constructs Research fronts/ knowledge bases Social network analysis: co-author, co- Indicators: number of articles, citation methods/ citation, co-word-networks etc. rate, h-Index, -

Appropriate Use of Bibliometric Indicators for the Assessment Of

Appropriate Use of Bibliometric Indicators for the Assessment of Journals, Research Proposals, and Individuals (Adopted by the IEEE Board of Directors 9 September 2013) Bibliometric indicators provide numerical scales that are intended to quantitatively determine the value of scientific research and the scholarly publication in which that research is published. Since scientific performance cannot, of course, be directly “measured”, citations acquired by each published paper are assumed as a proxy for quality, without prejudging the reasons for the citations. The application of bibliometrics to quantify the significance of individual journals dates back several decades [1] and the field has now reached a sufficiently high level of maturity to recognize that the scientific impact of journals as evaluated by bibliometrics is a complex, multi-dimensional construct and therefore more than one indicator is needed for such evaluation [2]-[4]. Nearly all commonly used bibliometric indices [1],[5]-[7] can be classified fundamentally as measuring either popularity or prestige, two concepts for which citation behaviors are valued in different and complementary ways. These indices also offer differing consideration of self-citations and have various levels of susceptibility to potential manipulation. As such, use of a single bibliometric index to rank, evaluate, and value journals is inappropriate. Rather, the use of multiple metrics with complementary features provides a more comprehensive view of journals and their relative placements in their fields. Recently, citation counts and proxies thereof have risen in importance as fundamental elements in the determination of the scientific impact of entire departments or universities and research centers [8], funding evaluations of research proposals and the assessment of individual scientists for tenure and promotion [9], salary raises [10], or even to predict future career success [11]. -

Understanding Research Metrics INTRODUCTION Discover How to Monitor Your Journal’S Performance Through a Range of Research Metrics

Understanding research metrics INTRODUCTION Discover how to monitor your journal’s performance through a range of research metrics. This page will take you through the “basket of metrics”, from Impact Factor to usage, and help you identify the right research metrics for your journal. Contents UNDERSTANDING RESEACH METRICS 2 What are research metrics? What are research metrics? Research metrics are the fundamental tools used across the publishing industry to measure performance, both at journal- and author-level. For a long time, the only tool for assessing journal performance was the Impact Factor – more on that in a moment. Now there are a range of different research metrics available. This “basket of metrics” is growing every day, from the traditional Impact Factor to Altmetrics, h-index, and beyond. But what do they all mean? How is each metric calculated? Which research metrics are the most relevant to your journal? And how can you use these tools to monitor your journal’s performance? For a quick overview, download our simple guide to research metrics. Or keep reading for a more in-depth look at what’s in the “basket of metrics” and how to interpret it. UNDERSTANDING RESEACH METRICS 3 Citation-based metrics Citation-based metrics IMPACT FACTOR What is the Impact Factor? The Impact Factor is probably the most well-known metric for assessing journal performance. Designed to help librarians with collection management in the 1960s, it has since become a common proxy for journal quality. The Impact Factor is a simple research metric: it’s the average number of citations received by articles in a journal within a two-year window. -

Westjem's Impact Factor, H-Index, and I10-Index

WESTJEM SECTION WestJEM’s Impact Factor, h-index, and i10-index: Where We Stand Calvin Tan, BS* * WestJEM Editorial Director Calvin He, BS† † WestJEM Publishing Manager Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH‡ ‡ WestJEM Managing Associate Editor As the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: versus review articles versus case reports etc.) to Integrating Emergency Care with Population name a few concerns.2,3 However, the JIF numbers Health (WestJEM) continues to grow, it is important calculated each year produce journal rankings that to remain aware of where we stand relative to mirror the common consensus of those in each our peers. During all stages WestJEM’s growth respective field placing the more well-known and and maturation as a journal we have strived to revered journals at the top. become and remain a relevant force in the world of While WestJEM will not have an official, academic publications. published impact factor until it is referenced in the Medline index, the current calculated 2012 JIF is The Journal Impact Factor 1.234. (374 citations in 2012 to articles published in The journal impact factor (JIF) is one way to 2011 and 2010 divided by 303 articles published in assess a journal’s status, and helps to weight the 2011 and 2010). difference between journals. The impact factor is a ratio that was initially started in 1975 to indicate the The h-index average reach and importance of articles published The h-index is short for the Hirsch index, which by a journal; it has since been additionally applied to was suggested by Dr. Jorge E. -

IEEE Open Access Solutions: Open.Ieee.Org

The Trusted Solution for Open Access Publishing Now Offering More Options for Authors and Institutions Resources on IEEE Publishing and Open Access Programs: For more information on IEEE open access solutions: open.ieee.org Open access is one part of the larger open science movement, helping to make scientific research and data For more information on IEEE Access: accessible to all, while speeding up the entire process—from lab discovery to the application of the research. ieeeaccess.ieee.org Heightened visibility, consistent quality, and industry credibility make IEEE publications trusted sources for researchers around the world. Visit the IEEE Xplore Digital Library: ieee.org/ieeexplore IEEE is working to enable these developments by creating more tools, services, and publication opportunities for authors and researchers. At the same time, IEEE strives to support the work and needs of all authors globally— IEEE Author Center: those who prefer to publish in traditional subscription journals or those who prefer or are required to publish via Featuring multiple tools to help authors get articles ready for submission quickly and easily, open access. including a publication recommender, article templates, graphics analyzer, PDF checker, and more. ieeeauthorcenter.ieee.org A Growing Collection of Open Access Options To help authors gain maximum exposure for their groundbreaking research and application-oriented articles, IEEE offers three options for open access (OA) publishing, all designed to meet the varying needs of authors throughout -

Impact Factor, H-Index, I10-Index and I20-Index of Webology

Webology, Volume 13, Number 1, June, 2016 Home Table of Contents Titles & Subject Index Authors Index Impact Factor, h-index, i10-index and i20-index of Webology Alireza Noruzi Editor-in-Chief of Webology; Assistant Professor, Department of Knowledge and Information Science, Faculty of Management, University of Tehran, Iran. E-mail: noruzi (at) ut.ac.ir Abstract The purpose of this editorial note was to conduct a citation analysis of the Webology journal in order to show the journal impact factor, h-index, i10-index, i20-index, and patent citations. This note indicates to what extent the Webology journal is used and cited by the international scientific community. The results show that the total number of citations to Webology papers on Google Scholar was 2423 and the total number of citations received by i20 papers (i.e., 24 papers with at least 20 citations) was 1693. This reveals that i20 papers received 70 percent of all citations to Webology. Keywords Citation analysis, Impact factor; H-index; i10-index; i20-index; Webology Introduction The publication of Webology was first started in August 2004 as an open access journal. It is an international peer-reviewed journal in English devoted to the field of the World Wide Web and serves as a forum for discussion and experimentation. It serves as a forum for new research in information dissemination and communication processes in general, and in the context of the World Wide Web in particular. There is a strong emphasis on the World Wide Web and new information and communication technologies. As the Webology journal continues to grow, it is important to remain aware of where we stand relative to our peers. -

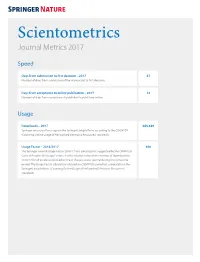

Scientometrics Journal Metrics 2017

Scientometrics Journal Metrics 2017 Speed Days from submission to first decision – 2017 47 Number of days from submission of the manuscript to first decision. Days from acceptance to online publication – 2017 13 Number of days from acceptance at publisher to published online. Usage Downloads – 2017 688,649 Springer measures the usage on the SpringerLink platform according to the COUNTER (Counting Online Usage of NeTworked Electronic Resources) standards. Usage Factor – 2016/2017 406 The Springer Journal Usage Factor 2016/17 was calculated as suggested by the COUNTER Code of Practice for Usage Factors. It is the median value of the number of downloads in 2016/17 for all articles published online in that particular journal during the same time period. The Usage Factor calculation is based on COUNTER-compliant usage data on the SpringerLink platform. (Counting Online Usage of NeTworked Electronic Resources) standards. Journal Metrics Impact Impact Factor – 2016 2.147 Journal Impact Factors are published each summer by Thomson Reuters via Journal Citation Reports®. Impact Factors and ranking data are presented for the preceding calendar year. 5 Year Impact Factor – 2016 2.346 The 5-year journal Impact Factor is the average number of times articles from the journal published in the past five years that have been cited in the JCR year. It is calculated by dividing the number of citations in the JCR year by the total number of articles published in the five previous years. SNIP – 2016 1.319 Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP) measures contextual citation impact by weighting citations based on the total number of citations in a subject field. -

Open Access and New Standards in Scientific Publishing

Open Access and New Standards in Scientific Publishing The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery DISCLOSURE INFORMATION Ernest E. Moore, MD – Nothing to disclose. Jennifer Crebs – Nothing to disclose. How did we get here? Timeline THE BEGINNING 15th century: Gutenberg‟s press spreads across Europe. ~1620s: The „Invisible College‟ era (Robert Boyle and friends). Books published. 1660s: Founding of the Royal Society (1660) and the French Academy of Sciences (1666). January 1665: First scholarly journal (Journal des sçavans) launches. March 1965: First scientific journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Scientific communication wed to print. PROGRESSION 1700s: The „Republic of Letters‟ – explosive growth and development of science. Letters written in duplicate, published (social networking, 18 th-century style) 1800s: The rise of specialties. Medical journals arrive on the scene, e.g. NEJM (1812), The Lancet (1823), JAMA (1883), Annals of Surgery (1885). Science as a profession supported by publication. MODERN ERA 1880s-1900s: Printing technology proliferates, but expensive. Publishers fill role of disseminating research. Focus on monographs. “The Watson and Crick paper 1960s: Adoption of peer review by was not peer-reviewed by some journals. Nature… the paper could not have been refereed: its 1965: The first citation index, correctness is self-evident. No practical birth of impact factor. referee working in the field could have kept his mouth 1970s: Journal articles start to adopt shut once he saw the specific format