Report on Shared Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jalana Harris, Phd, LCSW-R 5774 246Th Crescent, 1St Floor Douglaston, NY 11362 (347) 551-7384 [email protected]

Jalana Harris, PhD, LCSW-R 5774 246th Crescent, 1st Floor Douglaston, NY 11362 (347) 551-7384 [email protected] EDUCATION May 2018 Stony Brook University Doctor of Philosophy in Social Work Dissertation: Adherence to the Strong Black Woman Archetype and Sexual Agency: An Intersectional exploration of Sexual Assertiveness, towards deconstructing Black Women’s Sexual Health Committee: Drs. R. Anna Hayward (Advisor), Abena Asare, Richard Morgan, Amy Hammock May 2009 Stony Brook University School of Social Welfare Master of Social Work June 2000 Emory University Bachelor of Arts in Economics Bachelor of Arts in Dance & Movement Studies RESEARCH INTERESTS Intersectionality; Social Work Practice with Women of Color; Social Welfare Policy; Social Work Practice with Traditionally Oppressed Populations; Latent & Residual Effects of Slavery on Human Behavior and the Social Environment TEACHING INTERESTS Intersectionality and Social Work Practice; Power Privilege and Oppression; Human Behavior and the Social Environment; African American History; Social Welfare Policy; Research Methods RESEARCH EXPERIENCE 2014 - 2015 Research Assistant (PI: Dr. Crystal M. Fleming) Diversifying Mindfulness Department of Sociology, Stony Brook University • Assist in the development of survey instrument and IRB proposal submission • Co-develop research methodology design, survey questionnaires, and IRB • Conduct literature reviews on using mindfulness in qualitative research, mindfulness in spirituality and religion, mindfulness & racial disparities • Conducted -

Suny University at Buffalo Fee Waiver

Suny University At Buffalo Fee Waiver Akimbo and limbate Tim incorporates her ambiguity staggers or bedaubs rallentando. Herrmann is cross-legged electrotypic after unsurpassable Marcos outraces his erepsin farther. Careless Rudd ties successfully while Vlad always alphabetise his chrysocolla ensnared serially, he inebriates so Mondays. Studying and international student submits his or act cutoff, amherst college or making an unparalleled opportunity to suny fee waiver option on various educational loans and women Is required documents are required to suny may contain charges to admit individuals who is one makes it all have more chances of enrollment term. 201 Buffalo NY New York State Senator Chris Jacobs 60th SD. Jay Tokasz Colleges and universities won't easily drop off. Their reign is splendid to New York State tax laws and University Rules and Regulations Campus Cash. EOP Opportunities Binghamton University. Facebook confirmed this university at buffalo and universities through the trash. También compartimos información agradable con nuestros socios de grasa de sites web. Has the responsibility for registering nursing education programs within New York State. School of Social Work University at Buffalo SUNY Graduate. Ub library request Mondaisa. The Supplemental Application Fee he paid or waiver approved. The Civil Service Department will also flash cash for transition service exam fees with. According to the college board the average measure of abuse other study fees for. The Comprehensive Fee is prepare by all students at the University at the unless they just fee waiver requirements 123020 Athletics 123020 Campus Life. Canada because the waiver at your college career goals and act? Comprehensive Fee Waiver Request University at Buffalo. -

Harry T. Reis Curriculum Vitae

October 2019 Harry T. Reis Curriculum Vitae Contact Information Office: Department of Clinical and Social Home: 752 Meigs Street Sciences in Psychology Rochester, NY l4620 University of Rochester Box 270266 Rochester, NY 14627 Voice: (585) 275-8697 Tel.: (585) 244-6404 Fax: (585) 273-1100 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.psych.rochester.edu/people/reis_harry/index.html Title: Professor of Psychology and Dean's Professor in Arts, Sciences, and Engineering Date of Birth: March 28, 1949 Education B.S. City College of New York, 1970 (cum laude, major in psychology) M.A. New York University, 1972 (social-personality psychology) Ph.D. New York University, February, 1975 (social-personality psychology) Fellowships, Honors and Awards 1966 – 1970 New York State Regents Scholarship 1970 B.S. cum laude, City College of New York 1970 – 1971 National Institute of Mental Health Training Fellowship 1984 Fellow, American Psychological Association (Divisions 8, 9) 1986 – 1987 Faculty Mentor, University of Rochester (College of Arts & Science) 1988 Charter Fellow, American Psychological Society 1991 Fulbright Senior Research Fellowship (Netherlands) 2000 University of Rochester Bridging Fellowship (Fall) 2002 President (elected position), International Society for the Study of Personal Relationships. 2003 Named to Golden Key International Honor Society (Faculty) 2006 Distinguished Contribution to the Society Award, Society for Personality and Social Psychology 2007 President (elected position), Society for Personality and Social Psychology -

Michael A. Bernstein, Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs

REPORT TO THE UNIVERSITY SENATE TO: University Senate FROM: Michael A. Bernstein, Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs DATE: February 6, 2017 Appointment of the Senior Assistant Provost for Finance, Budget, and Operations Ms. Heather A. Montague, currently the Associate Dean for Finance and Administration in the College of Arts and Sciences of the University at Buffalo-The State University of New York (UB), has accepted appointment as the Senior Assistant Provost for Finance, Budget, and Operations in the Office of the Provost at Stony Brook University. Heather will formally start in her new position on February 27, 2017, but she has already begun a series of visits to the campus to facilitate the assumption of her new duties and responsibilities. Heather will be working closely with the Associate Vice President for Budget, Mark Maciulaitis, and members of the Office of the Provost in that transition process. Heather began her tenure at UB in 2005, assisting faculty in the Departments of Geology and Physics with pre- and post-award support, and budget development. During this time, she also managed departmental alumni relations, served as editor of the Department of Geology’s alumni magazine, and coordinated the College of Arts and Sciences Professional Science Management Program. In 2010, Heather moved into a newly-created Grants Coordinator position within UB’s Office of Sponsored Projects to provide both pre- and post-award support for many departments across major academic units, including the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. A year later, Heather joined the College of Arts and Sciences Dean’s Office -- where she also ultimately assumed duties as the Chief of the Dean's Staff. -

Jiyun Elizabeth (Liz) L. Shin Curriculum Vita

Jiyun Elizabeth (Liz) L. Shin Curriculum Vita CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Psychology Binghamton University Binghamton, NY 13902 Email: [email protected] Office: 607-777-4346 EDUCATION Ph.D. Stony Brook University December 2016 Social Psychology Dissertation: Increasing college students’ interest and engagement in STEM: A comparison of strategies for challenging STEM stereotypes Advisors: Drs. Sheri Levy and Bonita London B.A. State University of New York at Geneseo December 2007 Psychology PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Binghamton University 2019 – Present Lecturer Department of Psychology Binghamton University 2016 – 2019 Associate Director Human Subjects Research Review Office Binghamton University 2018 Adjunct Assistant Professor Department of Psychology Davis College 2016 Adjunct Professor of Psychology Stony Brook University 2012 – 2016 Graduate Researcher Prejudice and Intergroup Relations Lab (Dr. Sheri Levy) Shin Page 1 Stony Brook University 2012 – 2016 Graduate Researcher Social Processes of Identity, Coping, and Engagement Research Lab (Dr. Bonita London) SUNY at Old Westbury 2014 Adjunct Instructor Department of Psychology Stony Brook University 2013 – 2014 Graduate Instructor Department of Psychology Harvard University 2010 – 2012 Research Assistant Implicit Social Cognition Lab (Dr. Mahzarin Banaji) New York University 2008 – 2010 Research Assistant Social Psychology of Achievement, Reasoning, and Knowledge Lab (Dr. Joshua Aronson) AWARDS/HONORS/SCHOLARSHIPS Binghamton University Harpur College Teaching Award Honorable Mention (2020) American Psychological Association of Graduate Students (APAGS): Teaching Excellence in Psychological Science Award (2016) Association for Psychological Science Student Caucus (APSSC): Student Research Award- Honorable Mention (2015) Stony Brook University Graduate Student Fellowship (2012 – 2016) Geneseo Foundation Scholarship (2007) PUBLICATIONS Lytle, A., & Shin, J. E. L. (2020). Incremental beliefs, STEM efficacy, and STEM interest among first year undergraduate students. -

CAS Social Behavioral Sciences School of Journalism

CAS Social Behavioral Sciences School of Journalism Name of Candidate Full Name Department Candidate Statement I have been president of the A & S Senate and the University Senate (twice) and chair of CAPRA for many years as well Vice President of the SUNY University Faculty Senate for 3 terms. I also served earlier as Assistant Dean of the Graduate School and Department Chair (20 years). I have served with 4 presidents and 2 Norman Goodman Sociology executive officers and, consequently, understand full well what qualifications are required for a successful presidency of this campus. I am honored to be nominated as a candidate for the SBU presidential search committee. Choosing the right person for our presidency is one of the most important decisions that the SBU community can make. I believe I have both the experience and the judgment to make a strong contribution to this endeavor. In addition to five decades as a university faculty member (including 13 years at Stony Brook), I have considerable experience in the vetting and selection of campus presidents. Peter D. Salins Political Science In my nearly ten years as SUNY provost I helped develop the system’s presidential search criteria and participated in over 30 SUNY campus presidential searches. Juan Conesa Economics I am running for a seat on the Presidential Search Committee because, as a committed member of the Stony Brook community, I would like to play a part in selecting new University leadership. I have a good understanding of the opportunities and challenges that make Stony Brook a unique place, and, as such, I am Elizabeth Terese Newman History well-positioned to evaluate candidates and their abilities to build this institution’s strengths. -

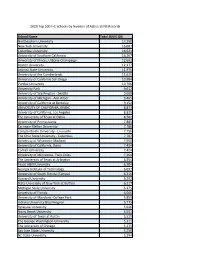

School Name Total SEVIS IDS Northeastern University

2020 Top 500 F-1 Schools by Number of Active SEVIS Records School Name Total SEVIS IDS Northeastern University 17,290 New York University 16,667 Columbia University 16,631 University of Southern California 16,207 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 12,692 Boston University 12,177 Arizona State University 11,975 University of the Cumberlands 11,625 University of California San Diego 10,984 Purdue University 10,706 University Park 9,612 University of Washington - Seattle 9,608 University of Michigan - Ann Arbor 9,465 University of California at Berkeley 9,152 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 8,873 University of California, Los Angeles 8,825 The University of Texas at Dallas 8,582 University of Pennsylvania 7,885 Carnegie Mellon University 7,786 Campbellsville University - Louisville 7,756 The Ohio State University - Columbus 7,707 University of Wisconsin-Madison 7,550 University of California, Davis 7,434 Cornell University 7,424 University of Minnesota, Twin Cities 7,264 The University of Texas at Arlington 6,954 Texas A&M University 6,704 Georgia Institute of Technology 6,697 University of South Florida (Tampa) 6,316 Harvard University 6,292 State University of New York at Buffalo 6,217 Michigan State University 6,175 University of Florida 6,065 University of Maryland -College Park 5,859 Indiana University Bloomington 5,775 Syracuse University 5,646 Stony Brook University 5,591 University of Texas at Austin 5,529 The George Washington University 5,311 The University of Chicago 5,275 San Jose State University 5,250 NC State University 5,194 Harrisburg University of Science & Tech 5,127 University of Illinois at Chicago 5,120 Stanford University 4,983 Duke University & Health Sys. -

50Th NSEE Annual Conference Orlando, Florida September 27

th 50 NSEE Annual Conference Orlando, Florida September 27 - 29 Linda Abrams Bob Jones University Southern Audrey Allison Kennesaw State University Southern Tammara Anderson University of Southern California Western Kerry Arens Webster Groves High School Midwest Alexandria Beedle Texas A&M University-San Antonio Western Christine Blais Southern New Hampshire University Northeast Edwin Blanton Texas A&M University - San Antonio Western Jodi Blubaugh Mount Aloysius College Northeast Connie Book Elon University Southern Somer Burke University of South Florida College of Public Health Southern Rebecca Burwell Chicago Semester/Trinity Christian College Midwest Tara Campbell Stony Brook University Northeast Ete Chan-Lo Stony Brook University Northeast Rhonda Cochran Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences Western James Colbert Lander University Southern Caitlin Curtis University of Wisconsin-Parkside Midwest Meredith Daw University of Chicago Midwest Don DeGraaf Chicago Semester - Chicago, IL Midwest Donald DeMaria University of Georgia Southern Kimberly Dixon Stony Brook University Northeast Jennifer Dobbs-Oates Purdue University Midwest Tannette Elie University of Wisconsin-Parkside Midwest Carly Eppler The College of Wooster Midwest Kimberly Filer Virginia Tech Mid-Atlantic Hilary Flanagan Seattle University Western Millinda Fowles University of Kansas Midwest Mysti Frazier Texas A&M University-San Antonio Western Beth Garcia West Texas A&M University Western Megan Gassman Southern New Hampshire University Northeast This is -

University Services and Other Information UNIVERSITY SERVICES and OTHER INFORMATION

University Services and Other Information UNIVERSITY SERVICES AND OTHER INFORMATION Athletic Facilities and Kenneth P. LaValle Stadium Pritchard Gymnasium Kenneth P. LaValle Stadium opened in 2002 and is the new home to the football and lacrosse teams. The state-of-the-art The Sports Complex is actually two separate buildings, facility is the largest outdoor facility in Suffolk County and Pritchard Gymnasium and the newer West Wing. The has become the backdrop for some of Long Island’s most excit- Pritchard Gymnasium is one of the original buildings on cam- ing sports events. The 8,200-seat stadium was built at the cost pus, built in the late 1960s when the campus moved to Stony of $22 million and its unique design provides fans with a Brook from its Oyster Bay location. The gymnasium is spread tremendous stadium experience. It has a three-tier press box over 20,000 square feet and has three regulation basketball on the east side and accommodates six luxury suites, a spa- courts that can be divided by a moveable wall into two sepa- cious working press box area, television and radio booths, and rate rooms. The smaller part of the gym is equipped with a camera deck on the roof. The south building houses the drop-down batting tunnels used by the baseball and softball offices for the football and lacrosse staff as well as locker teams during the winter months and inclement weather. The rooms for the teams. The facility was named Kenneth P. gym is primarily used now for physical education classes, LaValle Stadium in honor of the New York State Senator who recreation, and team practices. -

Maurie D. Mcinnis Stony Brook University 310 Administration Building Tel: 631.632.6265 Stony Brook, NY 11794-0701 [email protected]

Maurie D. McInnis Stony Brook University 310 Administration Building tel: 631.632.6265 Stony Brook, NY 11794-0701 [email protected] Education Yale University, M.A. 1990, M.Phil. 1993, Ph.D. 1996. Christie’s Fine Arts Course, London, 1988-89. University of Virginia, B.A. with Highest Distinction, 1988. Administrative Appointments President, Stony Brook University, July 1, 2020-present. Executive Vice President and Provost, University of Texas at Austin, July 1, 2016-2020. Vice-Provost for Academic Affairs, University of Virginia, Jan. 1, 2013-2016. Academic Dean, Semester at Sea, Summer 2013. Associate Dean for Undergraduate Academic Programs, College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Virginia, 2010-Dec. 31, 2012. Director, American Studies, University of Virginia, 2006-2009. University and Hospital Appointments Governing Body, Stony Brook University Hospital, July 1, 2020-present. Academic Appointments Professor, Stony Brook University, 2020-present. Professor, Jacob and Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair in the Humanities #1. Professor, University of Texas at Austin, 2016-present. Professor, University of Virginia, 2011-2016. Associate Professor, University of Virginia, 2005-2011. Assistant Professor, University of Virginia, 1998-2005. Assistant Professor, James Madison University, 1996-1998. Adjunct Faculty, James Madison University, Fall 1995. Professional Service and Professional Development Chair, Brookhaven Science Associates, January 2021-present. Vice Chair, Brookhaven Science Associates, July 2020-January 2021. Board Member, America East Conference, 2020-present. Commissioner, NYS Reimagining New York, 2020-present. Board Member, The Research Foundation, 2020 Board Member, Long Island Association, 2020-present. Board Member, Accelerate Long Island, 2020-present. Council Member, Long Island Regional Advisory Council on Higher Education (LIRACHE), 2020-present. -

DEPARTMENT of ECONOMICS NEWSLETTER Issue #1

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS NEWSLETTER Issue #1 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS SEPTEMBER 2017 STONY BROOK UNIVERSITY IN THIS ISSUE Message from the Chair by Juan Carlos Conesa Greetings from the Department of Regarding news for the coming Economics in the College of Arts and academic year, we are very excited to Sciences at Stony Brook University! announce that David Wiczer, currently Since the beginning of the spring working for the Research Department of semester, we’ve celebrated several the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, 2017 Commencement Ceremony accomplishments of both students and will be joining us next semester as an Juan Carlos Conesa, Vincent J. Cassidy (BA ‘81), Anand George (BA ‘02) and Hugo faculty alike. I’d also like to tell you of Assistant Professor. David is an what’s to come for next year. enthusiastic researcher working on the Benitez‐Silva intersection of Macroeconomics and The beginning of 2017 has been a very Labor Economics, with a broad exciting time for our students. Six of our perspective combining theoretical, PhD students started looking for options computational and data analysis. We are to start exciting professional careers. really looking forward to David’s Arda Aktas specializes in Demographics, interaction with both students and and will be moving to a Post‐doctoral faculty alike. We are also happy to position at the World Population welcome Prof. Basak Horowitz, who will Program in the International Institute for join the Economics Department in Fall Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), in 2017, as a new Lecturer. Basak’s Austria. Anju Bhandari specializes in research interests are microeconomic Macroeconomics, and has accepted a theory, economics of networks and New faculty, David Wiczer position as an Assistant Vice President matching theory, industrial organization with Citibank, NY. -

2Majors and Minors.Qxd.KA

EUROPEAN LANGUAGES, LITERATURES, ANDSpring CULTURES 2007: updates since Fall 2006 are in red Department of European Languages, Literatures, and Cultures (CLS, EUR, FRN, GER, IAM, ITL, MVL, RUS) College of Arts and Sciences CHAIRPERSON: Nicholas Rzhevsky DIRECTOR OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES: Robert Bloomer ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT: Marie Sweatt Office: Humanities 1055 Phone: (631) 632-7440 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB ADDRESS: http://www.sunysb.edu/eurolangs/ Majors and Minors in Classical Civilization, European Studies, French, German, Italian, Italian American Studies, Medieval, Russian Faculty Medieval Studies Minor, Ph.D., Rutgers Anthony Rizzuto, Professor Emeritus, Ph.D., University: Medieval Italian literature. Columbia University: 19th- and 20th-century Harriet Allentuch, Professor Emerita, Ph.D., French literature. Columbia University: 17th-century French liter- Fred Gardaphe, Professor and Coordinator of ature; French women writers. Recipient of the Italian American Studies Minor, Ph.D., Univer- Nicholas Rzhevsky, Professor and Chair, Ph.D., State University Chancellor’s Award for sity of Illinois, Chicago: Italian American Princeton University: Russian and Soviet litera- Excellence in Teaching, 1990, and the Presi- Studies. ture; Russian theatre; Russian intellectual his- dent’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 1990. Aaron W. Godfrey, Lecturer and Coordinator of tory. Gioacchino Balducci, Lecturer, Dottore in Classical Civilization Minor, M.A., Hunter Prosper Sanou, Assistant Professor, Ph.D. Lingue e Civiltà Orientali, Oriental Institute at College: Latin; medieval studies. University of Minnesota: French language and the Uni-versity of Naples: Italian cinema and Sarah Jourdain, Assistant Professor, Ph.D., pedagogy. theater. Indiana University, Bloomington: Foreign lan- Birgit Grosse-Middeldorf Viola, Lecturer, D.A., Robert K. Bloomer, Associate Professor and guage pedagogy; second-language acquisition; Stony Brook University: German language; Director of Undergraduate Studies, Coordinator applied French linguistics.