Saratoga National Historical Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somalia's Mighty Shilling

Somalia’s mighty shilling The Economist March 31, 2012 1 / 12 Hard to kill • A currency issued in the name of a central bank that no longer exists 2 / 12 An expression of faith • Use of a paper currency is normally taken to be an expression of faith in the government that issues it • Once the solvency of the issuer is in doubt, anyone holding its notes will quickly try to trade them in for dollars, jewellery or, failing that, some commodity with enduring value 3 / 12 An exception • When the rouble collapsed in 1998 some factory workers in Russia were paid in pickles • The Somali shilling, now entering its second decade with no real government or monetary authority to speak of, is a splendid exception to this rule 4 / 12 A central bank • Somalia’s long civil war has ripped apart what institutions it once had • In 2011 the country acquired a notional central bank under the remit (authority) of the Transitional Federal Government • But the government’s authority does not extend far beyond the capital, Mogadishu. 5 / 12 Backed by no reserves • Why are Somali shillings, issued in the name of a government that ceased to exist long ago and backed by no reserves of any kind, still in use? 6 / 12 Supply xed • One reason may be that the supply of shillings has remained fairly xed • The lack of an ocial printing press able to expand the money supply has the pre-1992 shilling a certain cachet (prestige) 7 / 12 Fakes • What about fakes? • Abdirashid Duale, boss of the largest network of banks in Somalia, says that his sta are trained to distinguish good fakes from the real thing before exchanging them for dollars 8 / 12 Money is useful • A second reason for the shilling’s longevity is that it is too useful to do away with • Large transactions, such as the purchase of a house, a car, or even livestock are dollarised. -

Dollarization in Tanzania

Working paper Dollarization in Tanzania Empirical Evidence and Cross-Country Experience Panteleo Kessy April 2011 Dollarization in Tanzania: Empirical Evidence and Cross-Country Experience Abstract The use of U.S dollar as unit of account, medium of exchange and store of value in Tanzania has raised concerns among policy makers and the general public. This paper attempts to shed some light on the key stylized facts of dollarization in Tanzania and the EAC region. We show that compared to other EAC countries, financial dollarization in Tanzania is high, but steadily declining. We also present some evidence of creeping transaction dollarization particularly in the education sector, apartment rentals in some parts of major cities and a few imported consumer goods such as laptops and pay TV services. An empirical analysis of the determinants of financial dollarization is provided for the period 2001 to 2009. Based on the findings and drawing from the experience of other countries around the world, we propose some policy measures to deal with prevalence of dollarization in the country. Acknowledgment: I am thankful to the IGC and the Bank of Tanzania for facilitating work on this paper. I am particularly grateful to Christopher Adam and Steve O’Connell for valuable discussions and comments on the first draft of this paper. However, the views expressed in this paper are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect the official views of any institution with which I’m affiliated. 2 Dollarization in Tanzania: Empirical Evidence and Cross-Country Experience 1. Introduction One of the most notable effects of the recent financial sector liberalization in Tanzania is the increased use of foreign currency (notably the U.S dollar) as a way of holding wealth and a means of transaction for goods and services by the domestic residents. -

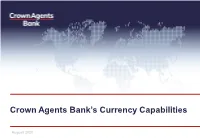

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

Gold, Silver and the Double-Florin

GOLD, SILVER AND THE DOUBLE-FLORIN G.P. DYER 'THERE can be no more perplexing coin than the 4s. piece . .'. It is difficult, perhaps, not to feel sympathy for the disgruntled Member of Parliament who in July 1891 expressed his unhappiness with the double-florin.1 Not only had it been an unprecedented addition to the range of silver currency when it made its appearance among the Jubilee coins in the summer of 1887, but its introduction had also coincided with the revival after an interval of some forty years of the historic crown piece. With the two coins being inconveniently close in size, weight and value (Figure 1), confusion and collision were inevitable and cries of disbelief greeted the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Goschen, when he claimed in the House of Commons that 'there can hardly be said to be any similarity between the double florin and the crown'.2 Complaints were widespread and minting of the double-florin ceased in August 1890 after scarcely more than three years. Its fate was effectively sealed shortly afterwards when an official committee on the design of coins, appointed by Goschen, agreed at its first meeting in February 1891 that it was undesirable to retain in circulation two large coins so nearly similar in size and value and decided unanimously to recommend the withdrawal of the double- florin.3 Its demise passed without regret, The Daily Telegraph recalling a year or two later that it had been universally disliked, blessing neither him who gave nor him who took.4 As for the Fig. -

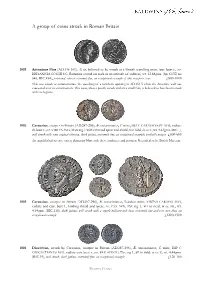

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

A REVIE\I\T of the COINAGE of CHARLE II

A REVIE\i\T OF THE COINAGE OF CHARLE II. By LIEUT.-COLONEL H. W. MORRIESON, F.s.A. PART I.--THE HAMMERED COINAGE . HARLES II ascended the throne on Maj 29th, I660, although his regnal years are reckoned from the death of • his father on January 30th, r648-9. On June 27th, r660, an' order was issued for the preparation of dies, puncheons, etc., for the making of gold and" silver coins, and on July 20th an indenture was entered into with Sir Ralph Freeman, Master of the Mint, which provided for the coinage of the same pieces and of the same value as those which had been coined in the time of his father. 1 The mint authorities were slow in getting to work, and on August roth an order was sent to the vVardens of the Mint directing the engraver, Thomas Simon, to prepare the dies. The King was in a hurry to get the money bearing his effigy issued, and reminders were sent to the Wardens on August r8th and September 2rst directing them to hasten the issue. This must have taken place before the end of the year, because the mint returns between July 20th and December 31st, r660,2 showed that 543 lbs. of silver, £r683 6s. in value, had been coined. These coins were considered by many to be amongst the finest of the English series. They fittingly represent the swan song of the Hammered Coinage, as the hammer was finally superseded by the mill and screw a short two years later. The denominations coined were the unite of twenty shillings, the double crown of ten shillings, and the crown of five shillings, in gold; and the half-crown, shilling, sixpence, half-groat, penny, 1 Ruding, II, p" 2. -

An Observance for Commonwealth Day 2012

AN OBSERVANCE FOR COMMONWEALTH DAY 2012 In the presence of Her Majesty The Queen, His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales and Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall Monday 12th March 2012 at 3.15pm Founded in 1868, today the Royal Commonwealth Society (RCS) is a modern charity working to promote international understanding. Its programmes range from creative writing, film and photography competitions to an innovative international youth leadership programme. Headquartered at London’s Commonwealth Club, the RCS has some 4,000 members in the UK and a presence in over 40 Commonwealth countries through a network of branches and Commonwealth societies. The RCS organises the Observance on behalf of the Council of Commonwealth Societies (CCS), and in consultation with the Dean of Westminster. www.thercs.org. To find out more, visit www.commonwealththeme.org Photographs from this event are available from www.picturepartnership.co.uk/events It is my great pleasure, as Chairman of the Council of Commonwealth Societies, to welcome you to this very special event. Each year, on the second Monday in March, the Council and the Royal Commonwealth Society are responsible for this occasion. The Observance marks Commonwealth Day, when people across the world celebrate the special partnership of nations, peoples, and ideals which constitutes the modern Commonwealth. The Observance is the UK’s largest annual multi-faith gathering, and today we are honoured by the presence of Head of the Commonwealth Her Majesty The Queen, His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales, Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall, the High Commissioners, and faith leaders of each major religion. -

The Coinage of Edward Vi in His Own Name

THE COINAGE OF EDWARD VI IN HIS OWN NAME W. J. W. POTTER PART I. SECOND PERIOD: JANUARY 1549 TO OCTOBER 1551 INTRODUCTION THE first period of Edward's coinage, from his accession in January 1547 to near the end of January 1549, was merely a continuation of the last period of his father's reign, and in fact the two indentures of April 1547 and February 1548, making up the first and second issues or coinages, provided merely for the continued striking of the current 20-ct. gold sovereigns and halves and the 4-oz. silver testoons, groats, and smaller money. Thus not only were the standards and denominations unaltered, but the only change in the great majority of coins was to be found on the half-sovereigns, where a youthful figure replaced that of the old king on the throne, though still with Henry's name. Only a very few half-sovereigns are known of this type actually bearing Edward's name. On the silver, where no change at all occurred, the coins of the two reigns are conveniently divided by the substitution of Roman letters for the old Lombardic lettering which occurred about this time, at first sometimes on one side only. The coinage of this first period has already been described and discussed in this Journal by Mr. C. A. Whitton in his articles entitled ' The Coinages of Henry VIII and Edward VI in Henry's Name' (vol. xxvi, 1949). These actually include the half-sovereigns in Edward's name mentioned above and also the rare groats with his name and profile portrait which were undoubtedly struck during this first period. -

5. UGANDA Rujumba George Williams

5. UGANDA Rujumba George Williams 5.1 Introduction Uganda, popularly referred to as ‘The Pearl of Africa’ is a small landlocked country covering a total area of 242,554 square kilometers, 17 percent of which is under water and marshland and 31.1 percent under forest cover. It is located in East Africa astride the equator and approximately between: 30 degrees and 35 degrees east of Greenwich and 4 degrees North and 1 degree, 30 minutes South of the equator. This is the region commonly referred to as the Great Lakes region due to the numerous lakes that characterizes it. Much of Uganda is a plateau 1000m to 3000m above sea level. There are numerous hills, valleys and extensive savannah plains and high mountains. Most of the eastern and northern regions are characterised by vast plains with occasional hills raising above these plains. The massive Mt. Elgon (Masaba) at 4321m along the border with Kenya creates the difference breaking the monotony of the plains. The central regions on the other hand, are dominated by L. Victoria (the second largest fresh water lake in the world) and the River Nile basin with numerous hills and swamps, especially papyrus swamps. In huge contrast, in the western and mid-western parts of the country are found beautiful volcanic highlands and rolling hills. There are also many small lakes and various volcanic features. The region is however dominated by the western rift valley-part of the Great Rift Valley system and Mt. Rwenzori ranges (popularly called the Mountains of the Moon) with its snow-capped peaks, which raises to 5176 m above sea level. -

February 2012 Invoice Charged Fee Be of $5Will Ifpayment Is Not and May at Doso No Charge Our When Lunches Are Held at Tower the Club

BAR NEWS February 2012 MONTHLY CLE LUNCH Law Enforcement Metropolitan Bar Sales Tax Speaker: Dan Patterson Greene County Prosecuting Attorney Wednesday, March 21, 2012 11:45 AM The Tower Club SPRINGFIELD Starlight Room, 22nd floor 901 E. St. Louis Street REGISTRATION In advance: $20.00 members, $25.00 non-members At the door: $25.00 members, $30.00 non-members Invoice fee of $5 will be charged if payment is not received on the date of the lunch. All full time judges are always welcome to attend and may do so at no charge when our lunches are 2012 SMBA President held at the Tower Club. At alternate locations the member discounted fee will apply. TERESA GRANTHAM Please note: non-members may only attend as • • • guests of SMBA members. Reservations accepted by phone, fax, mail or e-mail. Features This Month Register online! www.smba.cc SMBA President Teresa Grantham: Installation Speech Installation Banquet Photo Album 2 : FEBRUARY 2012 by Teresa Grantham 2012 SMBA President In response to numerous requests by members, Going back just a smidge further than Justice this month’s President’s message is a printing of Teresa Cardozo, Shakespeare taught a little legal procedure Grantham’s President’s Remarks at the 2012 SMBA in The Merchant of Venice. Shylock has a breach of Installation Banquet: contract case. He refuses the merchant’s offer of treble damages in lieu of the pound of flesh that Every year, one of the main priorities of the board judgment on the contract would demand. Portia is how best to maintain and increase collegiality finds a loophole. -

The Bank of England and Earlier Proposals for a Decimal ,Coinage

The Bank of England and earlier proposals for a decimal ,coinage The introduction of a decimal system of currency in Febru ary 1971 makes it timely to recall earlier proposals for decimalisation with which the Bank were concerned. The establishment of a decimal coinage has long had its advocates in this country.As early as 1682 Sir William Petty was arguing in favour of a system which would make it possible to "keep all Accompts in a way of Decimal Arith metick".1 But the possibility of making the change did not become a matter of practical politics until a decade later, when the depreciated state of the silver currency made it necessary to undertake a wholesale renewal of the coinage. The advocates of decimalisation, including Sir Christopher Wren - a man who had to keep many 'accompts' - saw in the forthcoming renewal an opportunity for putting the coin age on a decimal basis.2 But the opportunity was not taken. In 1696 - two years after the foundation of the Bank - the expensive and difficult process of recoinage was carried through, but the new milled coins were issued in the tra ditional denominations. Although France and the United States, for different reasons, adopted the decimal system in the 18th century, Britain did not see fit to follow their example. The report of a Royal Commission issued in 1819 considered that the existing scale for weights and measures was "far more con venient for practical purpose,s than the Decimal scale".3 The climate of public opinion was, however, changing and in 1849 the florin was introduced in response to Parliamentary pressure as an experimental first step towards a decimal ised coinage. -

Depreciation of the Ugandan Shilling: Implications for the National Economy

DEPRECIATION59th Session OF of theTHE State of UGANDANthe Nation Platform SHILLING: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE NATIONAL ECONOMY 59TH SESSION OF THE STATE OF THE NATION PLATFORM REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS 7TH AUGUST, 2015 AT PROTEA HOTEL KAMPALA Barbara Ntambirweki and Emma Jones STON Infosheet 59-Series 36, 2016 Abstract Over the course of 2014/15 fiscal year, State of the Nation (STON) Platform the Ugandan shilling depreciated to bring together key stakeholders against the US dollar by over 20%. for discussions on the likely impact Uganda, like many other economies, of the falling value of the Ugandan was struggling with the falling value shilling. Titled the “Depreciation of of its’ currency against the dollar the Ugandan Shilling: Implications for which was attributed to the fall in the National Economy”, three main export commodity prices, heavily recommendations emerged; chief impacted by export markets. This among them was the need to prioritise depreciation made mobilizing capital investment in the agricultural sector. from international markets difficult. Second was the need to pursue import Given the circumstances and the substitution and export promotion, and depreciation of the Ugandan shilling, thirdly the Government of Uganda long-term ramifications for the (GoU) was advised to prioritise the economy were likely. It was against adoption of an updated national this background that the Advocates monetary policy that reflected current Coalition for Development and economic needs. Environment (ACODE) held the 59th 1 DEPRECIATION OF THE UGANDAN SHILLING: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE NATIONAL ECONOMY Introduction Background The 59th STON Platform focused The 59th STON Platform was called at on understanding the implications a time when the value of the Ugandan of the depreciating value of the shilling had reached a record low of Ugandan shilling for the economy.