The Katakarajavamsavali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q U Alificatio N C O Lleg E U N Iversity Year D Esig N Atio N D Ep Artmen T N Ame O F Th E in Stitu Tio N F Ro M D D /MM/Y Y

Faculty Profile, MKCG Medical College & Hospital, Berhampur Details of teaching experience (designations / Promotions / Transfers / Qualification Resignations / Joining) Name Sl. No. Sl. As ……… As year Department College University Institution Department Name of theof Name Designation Qualification Present DesignationPresent Present DesignationPresent Date of Joiningofthe in Date Joiningofthe in Date ToDD/MM/YYY FromDD/MM/YYY Present institution ………institution Present yearsand months Totalexperience in Name of the Department : ANAESTHESIOLOGY SCB MC, SCB MC, Utkal Anaesthesi Cuttack 14.12.1995 26.10.1998 M.B.B.S. 1987 Tutor / Lecturer 7 Years Cuttack University ology SVPPGIP, 27.10.1998 27.08.2002 Cuttack SCB MC, Cuttack 28.08.2002 04.06.2004 SCB MC, Utkal Assistant Anaesthesi M.D. / M.S. ( ) 1993 VSS MC, 08.09.2004 10.10.2006 6 Years Cuttack University Professor ology Burla Anaesthesi 28.12.2016 as 11.10.2006 24.07.2008 1 Dr. Laxmidhar Dash Professor 14.12.2012 SCB MC, ology Professor Cuttack Associate Anaesthesi SCB MC, D.M / M.Ch 25.07.2008 13.12.2012 4 Years Professor ology Cuttack VSS MC, Burla 14.12.2012 10.07.2015 Anaesthesi 5 Years 7 Professor SCB MC, 11.07.2015 25.02.2016 ology Months Cuttack 28.12.2016 Continuing MKCG MC, Bam VSS MC, Burla 21.12.1995 12.01.1999 SCB MC, Utkal Anaesthesi 7 Years 3 M.B.B.S. 1989 Tutor / Lecturer SCB MC, 19.01.1999 16.09.2002 Cuttack University ology Months Cuttack 17.09.2002 22.06.2005 SVPPGIP, Cuttack Anaesthesi 11.11.2016 as SCB MC, Utkal Assistant Anaesthesi SCB MC, 6 Years 3 2 Dr. -

Global Journal of Human Social Science the Engagement Patters (Such As Listening)

OnlineISSN:2249-460X PrintISSN:0975-587X DOI:10.17406/GJHSS AnalysisofIslamicSermon PortrayalofRohingyaWomen NabakalebaraofLordJagannath TheRe-EmbodimentoftheDivine VOLUME20ISSUE7VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Global Journal of Human-Social Science: C Sociology & Culture Volume 2 0 I ssue 7 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Social Sciences. 2020. Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals ® Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO 945th Concord Streets, 6FLHQFHV´ Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ Global Journals Incorporated VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, SHUPLVVLRQ Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom 7KHRSLQLRQVDQGVWDWHPHQWVPDGHLQWKLV ERRNDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRUVFRQFHUQHG 8OWUDFXOWXUHKDVQRWYHULILHGDQGQHLWKHU -

INTEGRATED DISTRICT LEVEL MANAGEMENT of IRRIGATION and AGRICULTURE in Odisha

Operational Plan and New Command Plan for INTEGRATED DISTRICT LEVEL MANAGEMENT OF IRRIGATION AND AGRICULTURE in Odisha 1 Operational Plan and New Command Plan for Integrated District level Management of Irrigation and Agriculture in Odisha i Disclaimer ACT (Action on Climate Today) is an initiative funded with UK aid from the UK government and managed by Oxford Policy Management. ACT brings together two UK Department for International Development programmes: The Climate Proofing Growth and Development (CPGD) programme and the Climate Change Innovation Programme (CCIP). The views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. Operational Plan and New Command Plan for Integrated District level Plan for Integrated Plan and New Command Operational in Odisha and Agriculture of Irrigation management ii Contents Executive Summary vi Chapter 1 1 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Vulnerability of Odisha to climate change and drought 2 1.2 Impacts of Recent Droughts in Odisha 3 1.3 Rational for district integrated irrigation and agriculture plan 3 1.4 Objectives 4 1.5 Approach and Methodology 4 1.6 Limitations 4 Chapter 2 5 2. Operation Plan 5 2.1. Background Information 5 2.1.1 Potential created from different sources 6 2.2. Mapping System and Services for Canal Operation Techniques (MASSCOTE) 7 2.2.1. Presentation of the methodology 7 2.3 Coverage of irrigation in different blocks in pilot districts 8 2.4 Assessment of gap between irrigation potential and actual utilization in a district 10 2.5 Bridging the gap 10 2.6. DIAP planning in brief 11 2.6.1. -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

Palm Leaf Manuscripts Inheritance of Odisha: a Historical Survey

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2019; 5(4): 77-82 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2019; 5(4): 77-82 Palm leaf manuscripts inheritance of Odisha: A © 2019 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com historical survey Received: 16-05-2019 Accepted: 18-06-2019 Dr. Jharana Rani Tripathy Dr. Jharana Rani Tripathy PDF Scholar Dept.of Sanskrit Pondicherry University, Introduction Pondicherry, India Odisha was well-known as Kalinga, Kosala, Odra and Utkala during ancient days. Altogether these independent regions came under one administrative control which was known as Utkala and subsequently Orissa. The name of Utkala has been mentioned in Mahabharata, Ramayana and Puranas. The existence of Utkala as a kingdom is found in Kalidas's Raghuvamsa. It is stated that king Raghu after having crossed the river Kapisa reached the Utkala country and finally went to Kalinga. The earliest epigraphic evidence to Utakaladesa is found from the Midnapur plate of Somdatta which includes Dandabhukti within its jurisdiction1. The plates record that while Sasanka was ruling the earth, his feudatory Maharaja Somadatta was governing the province of Dandabhukti adjoining the Utkala-desa. The Kelga plate 8 indicate s that Udyotakesari's son and successors of Yayati ruled about the 3rd quarter of eleventh century, made over Kosala to prince named Abhimanyu and was himself ruling over Utkala After the down-fall of the Matharas in Kalinga, the Gangas held the reines of administration in or about 626-7 A, D. They ruled for a long period of about five hundred years, when, at last,they extended their power as far as the Gafiga by sujugating Utkala in or about 1112 A. -

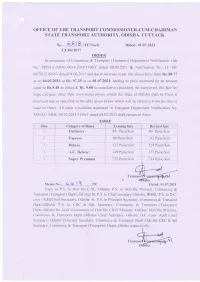

Order No 6618 (Revised Bus Fare W.E.F. 01.07.2021)

O F' I.' I C t.] O F' 1' I I E'T II.AN S PO R't CO M N{ I S S I O N I.] II-C TJ M-C H A I I{. M A N S'I'A'I-II ]' TIA NS I'OR]' A I.J'I' I IOIII'I'Y, O DI SH A. C [JT]'AC K. No... .Q.h.|.ft,..r'r' cn I)aterl: 01.07 .2021 ",t t.x-06t2{'lt7 ORDER In pursuarrce o1'Commerce & Transport ('fransport) De partment Notiflcation vidc 'l'ltN-t.C-MIS('-0011-20l4lll96l'1' No: dated 08.02.2021 & Notillcatiorr No: l.C-'ftt- 6tt/20151365411' clated 0.1.06.2015 and duc to incrcasc in per litrc dicsel pricc fiom Rs.88.77 as on 04.03.2021 to lts. 97.25 as on 01.07.2021" leading to price increased by an amount ccpral to Rs.8.,ltl irr direct & Rs.9.08 in cumulative (including the carryover). the larc fbr stailc carriages other than torr,rr buses plyirrg r,r,ithin thc Statc of Odisha shall bc llxccl ar incrcased rate as spccitied in thc tahlc given bclor,v rvhich will be ellective fiorn tlre c'latc of -fransport issue ot'Order. All othcr conclitions stipLrlate'd in Departrnent Notitlcation No: 1'RN-l.C-MISC-0014-2Ol4ll lt)61'l- ilated 08.01.2021 shall renrain in force. TABLE Category ol'Buses Ilxisting fare Revisecl fnrer Ortlinrll'1' 85 I'}aise/Krn 89 Paisc/l(rn Il x p rcss 89 Paise/Km 93 Paise/Krn f Z9 Paisel(," 157 Paisc/Krn SuJrcr Premium 2i2 I'}aisciKrn 244 I)aisc/Km lprrxti$qe.2l Mcnr,No: LG l9 l)atctl: 01.07.202I Copl'to P.S. -

PURI DISTRICT, ORISSA South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar

Govt. of India MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD PURI DISTRICT, ORISSA South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar March, 2013 1 PURI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl ITEMS Statistics No 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) 3479 ii. Administrative Divisions as on 31.03.2011 Number of Tehsil / Block 7 Tehsils, 11 Blocks Number of Panchayat / Villages 230 Panchayats 1715 Villages iii Population (As on 2011 Census) 16,97,983 iv Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1449.1 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Very gently sloping plain and saline marshy tract along the coast, the undulating hard rock areas with lateritic capping and isolated hillocks in the west Major Drainages Daya, Devi, Kushabhadra, Bhargavi, and Prachi 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest Area 90.57 b) Net Sown Area 1310.93 c) Cultivable Area 1887.45 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Alfisols, Aridsols, Entisols and Ultisols 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS Paddy 171172 Ha, (As on 31.03.2011) 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and Number of Structures) Dugwells, Tube wells / Borewells DW 560Ha(Kharif), 508Ha(Rabi), Major/Medium Irrigation Projects 66460Ha (Kharif), 48265Ha(Rabi), Minor Irrigation Projects 127 Ha (Kharif), Minor Irrigation Projects(Lift) 9621Ha (Kharif), 9080Ha (Rabi), Other sources 9892Ha(Kharif), 13736Ha (Rabi), Net irrigated area 105106Ha (Total irrigated area.) Gross irrigated area 158249 Ha 7. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB ( As on 31-3-2011) No of Dugwells 57 No of Piezometers 12 10. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Alluvium, laterite in patches FORMATIONS 11. HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water bearing formation 0.16 mbgl to 5.96 mbgl Pre-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 2 Sl ITEMS Statistics No Post-monsoon Depth to water level during 0.08 mbgl to 5.13 mbgl 2011 Long term water level trend in 10 yrs (2001- Pre-monsoon: 0.001 to 0.303m/yr (Rise) 0.0 to 2011) in m/yr 0.554 m/yr (Fall). -

Draft District Survey Report (Dsr) of Jagatsinghpur District, Odisha for River Sand

DRAFT DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) OF JAGATSINGHPUR DISTRICT, ODISHA FOR RIVER SAND (FOR PLANNING & EXPLOITING OF MINOR MINERAL RESOURCES) ODISHA As per Notification No. S.O. 3611(E) New Delhi, 25th July, 2018 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE (MoEF & CC) COLLECTORATE, JAGATSINGHPUR CONTENT SL NO DESCRIPTION PAGE NO 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OVERVIEW OF MINING ACTIVITIES IN THE DISTRICT 2 3 LIST OF LEASES WITH LOCATION, AREA AND PERIOD OF 2 VALIDITY 4 DETAILS OF ROYALTY COLLECTED 2 5 DETAILS OF PRODUCTION OF SAND 3 6 PROCESS OF DEPOSIT OF SEDIMENTS IN THE RIVERS 3 7 GENERAL PROFILE 4 8 LAND UTILISATION PATTERN 5 9 PHYSIOGRAPHY 6 10 RAINFALL 6 11 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL WALTH 7 LIST OF PLATES DESCRIPTION PLATE NO INDEX MAP OF THE DISTRICT 1 MAP SHOWING TAHASILS 2 ROAD MAP OF THE DISTRICT 3 MINERAL MAP OF THE DISTRICT 4 LEASE/POTENTIAL AREA MAP OF THE DISTRICT 5 1 | Page PLATE NO- 1 INDEX MAP ODISHA PLATE NO- 2 MAP SHOWING THE TAHASILS OF JAGATSINGHPUR DISTRICT Cul ••• k L-. , •....~ .-.-.. ••... --. \~f ..•., lGte»d..) ( --,'-....• ~) (v~-~.... Bay of ( H'e:ngal 1< it B.., , . PLATE NO- 3 MAP SHOWING THE MAJOR ROADS OF JAGATSINGHPUR DISTRICT \... JAGADSINGHPU R KENDRAPARA \1\ DISTRICT ~ -,---. ----- ••.• "'1. ~ "<, --..... --...... --_ .. ----_ .... ---~.•.....•:-. "''"'\. W~~~~~·~ ~~~~;:;;:2---/=----- ...------...--, ~~-- . ,, , ~.....••.... ,. -'.__J-"'" L[GEND , = Majar Roaod /""r •.•.- •.... ~....-·i Railway -- ------ DisAJict '&IWldEIIY PURl - --- stale Baumlallji' River Map noI to Sl::a-,~ @ D~triGlHQ CopyTig:hI@2012w_mapso,fin.dia_oo:m • OlllerTi:nim (Updated on 17th iNll~el'llber 2012) MajorTcown PREFACE In compliance to the notification issued by the Ministry of Environment and Forest and Climate Change Notification no. -

Sacred Space on Earth : (Spaces Built by Societal Facts)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 4 Issue 8 || August. 2015 || PP.31-35 Sacred Space On Earth : (Spaces Built By Societal Facts) Dr Jhikmik Kar Rani Dhanya Kumari College, Jiaganj, Murshidabad. Kalyani University. ABSTRACT: To the Hindus the whole world is sacred as it is believed to spring from the very body of God. Hindus call these sacred spaces to be “tirthas” which is the doorway between heaven and earth. These tirthas(sacred spaces) highlights the great act of gods and goddesses as well as encompasses the mythic events surrounding them. It signifies a living sacred geographical space, a place where everything is blessed pure and auspicious. One of such sacred crossings is Shrikshetra Purosottam Shetra or Puri in Orissa.(one of the four abodes of lord Vishnu in the east). This avenue collects a vast array of numerous mythic events related to Lord Jagannatha, which over the centuries attracted numerous pilgrims from different corners of the world and stand in a place empowered by the whole of India’s sacred geography. This sacred tirtha created a sacred ceremonial/circumbulatory path with the main temple in the core and the secondary shrines on the periphery. The mythical/ritual traditions are explained by redefining separate ritual (sacred) spaces. The present study is an attempt to understand their various features of these ritual spaces and their manifestations in reality at modern Puri, a temple town in Orissa, Eastern India. KEYWORDS: sacred geography, space, Jagannatha Temple I. Introduction Puri is one of the most important and famous sacred spaces (TirthaKhetra) of the Hindus. -

History of the Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie

History Of The Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie THE HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES. ORIGIN. THE CLAN MACKENZIE at one time formed one of the most powerful families in the Highlands. It is still one of the most numerous and influential, and justly claims a very ancient descent. But there has always been a difference of opinion regarding its original progenitor. It has long been maintained and generally accepted that the Mackenzies are descended from an Irishman named Colin or Cailean Fitzgerald, who is alleged but not proved to have been descended from a certain Otho, who accompanied William the Conqueror to England, fought with that warrior at the battle of Hastings, and was by him created Baron and Castellan of Windsor for his services on that occasion. THE REPUTED FITZGERALD DESCENT. According to the supporters of the Fitzgerald-Irish origin of the clan, Otho had a son Fitz-Otho, who is on record as his father's successor as Castellan of Windsor in 1078. Fitz-Otho is said to have had three sons. Gerald, the eldest, under the name of Fitz- Walter, is said to have married, in 1112, Nesta, daughter of a Prince of South Wales, by whom he also had three sons. Fitz-Walter's eldest son, Maurice, succeeded his father, and accompanied Richard Strongbow to Ireland in 1170. He was afterwards created Baron of Wicklow and Naas Offelim of the territory of the Macleans for distinguished services rendered in the subjugation of that country, by Henry II., who on his return to England in 1172 left Maurice in the joint Government. -

Professor Horace Hayman Wilson, Ma, Frs

PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN: PROFESSOR HORACE HAYMAN WILSON, MA, FRS “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project People of A Week and Walden HDT WHAT? INDEX PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN: HORACE HAYMAN WILSON A WEEK: A Hindoo sage said, “As a dancer, having exhibited herself PEOPLE OF to the spectator, desists from the dance, so does Nature desist, A WEEK having manifested herself to soul —. Nothing, in my opinion, is more gentle than Nature; once aware of having been seen, she does not again expose herself to the gaze of soul.” HORACE HAYMAN WILSON HENRY THOMAS COLEBROOK WALDEN: Children, who play life, discern its true law and PEOPLE OF relations more clearly than men, who fail to live it worthily, WALDEN but who think that they are wiser by experience, that is, by failure. I have read in a Hindoo book, that “there was a king’s son, who, being expelled in infancy from his native city, was brought up by a forester, and, growing up to maturity in that state imagined himself to belong to the barbarous race with which he lived. One of his father’s ministers having discovered him, revealed to him what he was, and the misconception of his character was removed, and he knew himself to be a prince. So soul,” continues the Hindoo philosopher, “from the circumstances in which it is placed, mistakes its own character, until the truth is revealed to it by some holy teacher, and then it knows itself to be Brahme.” I perceive that we inhabitants of New England live this mean life that we do because our vision does not penetrate the surface of things. -

Exposure Visit at CIFA During - 2015

Exposure Visit at CIFA during - 2015 Date From where come Visitor Category Total Male Female SC ST Other 06.01.15 PD Watershed, Rayagada district 35 25 10 35 07.01.15 College of Fisheries, OUAT, Rangeilunda, Ganjam 18 24 42 09.01.15 Tata Steel Gopalpur Project-EDII 19 19 EDII, Bhubaneswar 12.01.15 College of Fisheries, Kawardha, Kabirdham, 20 7 27 Chhatisgarh 12.01.15 B.F.Sc. Students of College of Fisheries, Guru 04 15 19 Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, Punjab 20.01.15 B-Tech Students from Gandhi Institute for 142 29 171 Technology, Bhubaneswar 21.01.15 Farmers from Bamara, Sambalpur, Odisha 22 22 23.01.15 Dept. of Zoology, B.S.N.V.P.G. College, Lucknow, 7 17 24 UP 28.01.15 Farmers of FTI, Balugaon 31 31 30.01.15 Farmers from Remuna, Balugaon, Odisha 17 17 07.02.15 Farmers, ATMA, Chhatrapur, Ganjam, Odisha 16 16 13.02.15 Students from Khalikote College, Berhampur, 04 16 20 Ganjam 16.02.15 Students from Raja N.L. Women’s College, Pachim 02 26 5 6 21 28 Medinipur, WB 18.02.15 Farmers from Jharkhand Training Institute, Ranchi, 32 5 6 21 32 Jharkhand 21.02.15 Farmers from Bolangir, IWMP-V, Odisha 11 05 5 5 6 16 26.02.15 Farmers from North Garo Hills district of Meghalaya 10 10 10 26.02.15 Farmers from Durg district of Chhatisgarh 13 1 11 1 13 28.02.15 Farmers from K. Singhpur, Rayagada, Odisha 03 10 11 2 13 04.03.15 Farmers from Rayagada, Odisha 14 02 16 09.03.15 Farmers from Balikuda, Jagatsinghpur, Odisha 29 2 27 29 11.03.15 Farmers from Tirtol & Raghunathpur, Jagatsinghpur, 25 25 25 Odisha 16.03.15 Farmers from Sohagpur, Shahdol, M.P.