Quantifying the Value of Real-Time Geodetic Constraints on Earthquake Early Warning Using a Global Seismic and Geodetic Dataset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Stake in the Shake: Earthquake Early Warning

A STAKE IN THE SHAKE: EARTHQUAKE EARLY WARNING When an earthquake happens, ShakeAlert STEM Classroom seismic waves travel outward in Discussion: all directions. Primary (P) waves travel faster than How would each of the situations secondary (S) waves and below be made more safe if people S waves do the most and automatic systems were alerted damage. But electronic that they were about to experience information can be sent faster than either wave. earthquake shaking? The ShakeAlert Earth- 1. A surgeon performing an operation. ave you ever felt an earthquake? quake Early Warning System can detect HWhat was it like? Where were you? an earthquake very quickly and send an 2. A chemistry teacher and students What did you do? How are people injured alert of imminent ground motion before working in a lab. during an earthquake? More than 143 mil- strong shaking arrives. 3. A warehouse or construction lion people are exposed to potentially worker. damaging shaking in the United States. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) along with universities and state 4. An amusement park with lots of agencies in Washington, Oregon, fast rides. MATERIALS: Nevada, and California are developing What other places could be made Computer with internet access the ShakeAlert Earthquake Early Warn- ing (EEW) System for the West Coast of safer with earthquake early warning? RESOURCES: the US. Several countries including What can you do to keep yourself ShakeAlert Factsheet (USGS) Japan, Mexico, Taiwan, and China already safe during an earthquake? https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/ -

An Earthquake Early Warning System for the West Coast of the United States

Technical Implementation Plan for the ShakeAlert Production System—An Earthquake Early Warning System for the West Coast of the United States Open-File Report 2014–1097 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey COVER IMAGE: Map generated from the ShakeAlert earthquake early warning system showing the initial 10 seconds of an M7.8 scenario earthquake on the southern San Andreas Fault. Expected warning times for the scenario earthquake are shown by red dashed lines with warning time labeled. Faults (solid dark-gray lines), length of the scenario rupture (dotted black line), and major cities (black dot with city name labeled) are shown. Purple, red, and yellow colors show instantaneous surface velocity of the earthquake, and this data is modified from the TeraShake simulation (www.scec.org/terashake). Technical Implementation Plan for the ShakeAlert Production System—An Earthquake Early Warning System for the West Coast of the United States By D.D. Given, E.S. Cochran, T. Heaton, E. Hauksson, R. Allen, P. Hellweg, J. Vidale, and P. Bodin Open-File Report 2014–1097 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2014 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Given, D.D., Cochran, E.S., Heaton, T., Hauksson, E., Allen, R., Hellweg, P., Vidale, J., and Bodin, P., 2014, Technical implementation plan for the ShakeAlert production system—An Earthquake Early Warning system for the West Coast of the United States: U.S. -

Exploring Perceptions of Shakealert During the 2019 Ridgecrest Earthquake Sequence

Failure to alert? Exploring perceptions of ShakeAlert during the 2019 Ridgecrest Earthquake Sequence Sara K. McBride, Ph.D. Social Science Research Coordinator – ShakeAlert Project Earthquake Science Center U.S. Geological Survey Jeannette Sutton2, Michele Marie Wood3, Lori Peek4, Robert M de Groot5, Andrea L Llenos6, Grace Alexandra Parker7, Danielle F Sumy8, Douglas D Given9, Pascal Schuback10, Ryan Arba11, Rachel Sierer- Co-Authors Wooden11, Emily Holland11, Holly Porter12, Candice Hadley12, Darius Fattahipour12, Alex Bell13 and Gabe Kearney14 1)U.S. Geological Survey, Earthquake Science Center, Kennewick, SPECIAL THANKS TO JASON United States, (2)University of Kentucky, Department of BAUMGARTNER, PUSHSHIFT Communication, Lexington, KY, United States, (3)California State University Fullerton, Fullerton, CA, United States, (4)University of Colorado Boulder, Sociology and Natural Hazards Center, Boulder, CO, United States, (5)United States Geological Survey - Earthquake Science Center, ShakeAlert Project, Pasadena, CA, United States, (6)USGS California Water Science Center Menlo Park, Menlo Park, CA, United States, (7)University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, (8)University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, (9)USGS, Pasadena, CA, United States, (10)Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup, Seattle, United States, (11)California Office of Emergency Services, Sacramento, United States, (12)San Diego Office of Emergency Services, San Diego, United States, (13)San Diego Office of Emergency Services, -

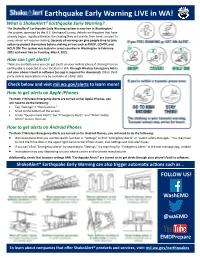

Earthquake Early Warning LIVE In

Earthquake Early Warning LIVE in WA! What is ShakeAlert® Earthquake Early Warning? The ShakeAlert® Earthquake Early Warning system is now live in Washington! The system, operated by the U.S. Geological Survey, detects earthquakes that have already begun, rapidly estimates the shaking they will create, then sends an alert to areas which will receive shaking. Seconds of warning can give people time to take action to protect themselves before shaking arrives such as DROP, COVER, and HOLD ON! The system was tested in select counties in Washington in February 2021 and went live on Tuesday, May 4, 2021. How can I get alerts? There are multiple ways you can get alerts on your mobile phone if shaking from an earthquake is expected at your location in WA: through Wireless Emergency Alerts and your phone’s built-in software (no app is required for download). Other third- party mobile applications may be available at a later date. Check below and visit mil.wa.gov/alerts to learn more! How to get alerts on Apple iPhones To check if Wireless Emergency Alerts are turned on for Apple iPhones, you will need to do the following: • Tap “Settings” > “Notifications.” • Scroll to the bottom of the screen. • Under “Government Alerts” tap “Emergency Alerts” and “Public Safety Alerts” to turn them on. How to get alerts on Android Phones To check if Wireless Emergency Alerts are turned on for Android Phones, you will need to do the following: • We recommend that you use the search function in “Settings” to find “Emergency Alerts” or “public safety messages." You may have to click the three dots in the upper right-hand corner of the screen, click settings and click alert types. -

The Community Seismic Network and Quake-Catcher Network: Enabling Structural Health Monitoring Through Instrumentation by Community Participants Monica D

The Community Seismic Network and Quake-Catcher Network: enabling structural health monitoring through instrumentation by community participants Monica D. Kohler*a, Thomas H. Heatona, Ming-Hei Chenga aDepartment of Mechanical and Civil Engineering; California Institute of Technology; Pasadena, CA 91125 ABSTRACT A new type of seismic network is in development that takes advantage of community volunteers to install low-cost ac- celerometers in houses and buildings. The Community Seismic Network and Quake-Catcher Network are examples of this, in which observational-based structural monitoring is carried out using records from one to tens of stations in a sin- gle building. We have deployed about one hundred accelerometers in a number of buildings ranging between five and 23 stories in the Los Angeles region. In addition to a USB-connected device which connects to the host’s computer, we have developed a stand-alone sensor-plug-computer device that directly connects to the internet via Ethernet or wifi. In the case of the Community Seismic Network, the sensors report both continuous data and anomalies in local acceleration to a cloud computing service consisting of data centers geographically distributed across the continent. Visualization models of the instrumented buildings’ dynamic linear response have been constructed using Google SketchUp and an associated plug-in to matlab with recorded shaking data. When data are available from only one to a very limited number of accelerometers in high rises, the buildings are represented as simple shear beam or prismatic Timoshenko beam mod- els with soil-structure interaction. Small-magnitude earthquake records are used to identify the first set of horizontal vi- brational frequencies. -

Failure to Alert? Exploring Perceptions of Shakealert During the 2019 Ridgecrest Earthquake Sequenceshow Affiliations

EGU21-13565 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-13565 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Failure to alert? Exploring perceptions of ShakeAlert during the 2019 Ridgecrest Earthquake SequenceShow affiliations Sara Mcbride1, Robert de Groot2, Tao Ruan3, Qin Lv4, and Qingkai Kong5 1U.S. Geological Survey, United States of America ([email protected]) 2U.S. Geological Survey, United States of America ([email protected]) 3University of Colorado- Boulder 4University of Colorado- Boulder 5University of California - Berkeley On July 4, 2019, a M6.4 earthquake struck Ridgecrest, California. The next evening, on July 5, an even larger M7.1 rattled the region. The ShakeAlert Earthquake Early Warning System for the West Coast of the United States detected and issued ShakeAlert Messages for both earthquakes to pilot users of the system. Several ShakeAlert technical partners, including the Caltech UserDisplay demonstration console, also delivered alerts to their users. However, the Los Angeles City application (app), powered by ShakeAlert, developed and being tested by the City of Los Angeles did not deliver ShakeAlerts to approximately 700,000 test users in Los Angeles County. This is because the alerting threshold of the estimated shaking (above Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) IV, potentially damaging shaking) was not met for either event in Los Angeles County. While the minimum magnitude threshold of M5.0 for both earthquakes was met, the shaking estimated by the ShakeAlert system indicated that no part of Los Angeles County would experience levels of shaking that would be damaging. Although the ShakeAlert System performed as designed—in both the Ridgecrest area as well as in Los Angeles—various media outlets and initial feedback from LA City app users suggest that the public perceived that the system did not work. -

Determination of Earthquake Early Warning Parameters, Τc and Pd, for Southern California

May 4, 2007 14:16 GeophysicalJournalInternational gji˙3430 Geophys. J. Int. (2007) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03430.x Determination of earthquake early warning parameters, τ c and Pd, for southern California Yih-Min Wu,1 Hiroo Kanamori,2 Richard M. Allen3 and Egill Hauksson2 1Department of Geosciences, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sec. 4th, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei 106, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected] 2Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 3Seismological Laboratory, Earth & Planetary Science, UC Berkeley, CA, USA Accepted 2007 February 28. Received 2007 February 28; in original form 2006 August 10 SUMMARY We explore a practical approach to earthquake early warning in southern California by deter- mining a ground-motion period parameter τc and a high-pass filtered displacement amplitude parameter Pd from the initial 3 s of the P waveforms recorded at the Southern California Seis- mic Network stations for earthquakes with M > 4.0. At a given site, we estimate the magnitude of an event from τc and the peak ground-motion velocity (PGV) from Pd. The incoming three- component signals are recursively converted to ground acceleration, velocity and displacement. The displacements are recursively filtered with a one-way Butterworth high-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 0.075 Hz, and a P-wave trigger is constantly monitored. When a trigger occurs, τc and Pd are computed. We found the relationship between τc and magnitude (M) for southern California, and between Pd and PGV for both southern California and Taiwan. These two relationships can be used to detect the occurrence of a major earthquake and provide onsite warning in the area around the station where onset of strong ground motion is expected within seconds after the arrival of the P wave. -

Disaster Recovery Reform Act and Earthquake Early Warning Systems

FEMA FACT SHEET Disaster Recovery Reform Act and Earthquake Early Warning Systems Fact sheet to explain how Section 1233 of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 is implemented under the Hazard Mitigation Assistance grant programs. Additional Hazard Mitigation Assistance grant programs information can be found in the HMA Guidance.1 Background On October 5, 2018, the President signed into law the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (DRRA) of 2018 as part of the Federal Aviation Administration Reauthorization Act of 2018. DRRA Section 1233 amends Section 404 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act), which authorizes funding for earthquake risk reduction activities under the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) and Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities Program (BRIC).2 Specifically, DRRA Section 1233 revised the Stafford Act by adding a new Section 404(g) to allow recipients of hazard mitigation assistance to leverage such funding to support building capability for earthquake early warning (EEW) systems. EEW systems use seismic instrumentation to monitor seismic activity in real time to detect significant earthquakes near the source and transmit those signals to a seismic monitoring network that can quickly send out a warning to alert people within the region before shaking arrives. Section 404(g) lists three categories of activities that support building capability for EEW: 1) regional seismic networks; 2) geodetic networks; and 3) seismometers, Global Positioning System receivers, and associated infrastructure.3 Activities Available for Hazard Mitigation Assistance Funding At this time, FEMA will consider proposals to fund the purchase and installation of seismometers, Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers, and the associated infrastructure (i.e., telemetry and signal processing) as needed to build additional capability for existing EEW systems designed as part of the Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS) under both HMGP and BRIC (Figure 1). -

SURVEY NOTES Volume 47, Number 3 September 2015

UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SURVEY NOTES Volume 47, Number 3 September 2015 A small step for Utahraptor, ONE BIG FOSSIL BLOCK FOR UGS PALEONTOLOGISTS Contents UGS Paleontolgists Collect Dinosaur Megablock ............................1 Deep Nitrate in an Alluvial Valley: Potential Mechanisms for Transport ....4 THE DIRECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE Energy News .............................................6 Teacher's Corner .......................................7 Glad You Asked ........................................8 Although the Utah Geo- ite at a depth of 5000 to GeoSights ................................................10 logical Survey (UGS) has 10,000 feet, easy all-year Survey News ............................................12 been struggling with a access, supportive land New Publications ....................................13 large decrease in exter- owners (Murphy Brown, nal funding, we are part LLC and Utah School and Design | Nikki Simon of a team that recently Institutional Trust Lands Cover | A track hoe pulls a nine-ton field jacket received an award for Administration), and mini- containing hundreds of bones of Utahraptor and iguanodont dinosaurs from the Stikes Quarry in eastern geothermal research. mal environmental issues. Utah. INSET PHOTO A reconstruction of the Stikes The Geothermal Tech- The UGS has already dinosaur death trap. Adult and juvenile Utahraptor dinosaurs attack an iquanodont dinosaur trapped in nology Office of the acquired the water rights quicksand. By Julius Costonyi. federal Department of by Richard G. Allis necessary -

Testimony of John Vidale, Ph.D. Professor, Dept of Earth and Space

Testimony of John Vidale, Ph.D. Professor, Dept of Earth and Space Sciences, Univ of Washington Director, Pacific Northwest Seismic Network Washington State Seismologist Hearing on: United States Geological Survey Oversight Before the US Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources April 7th, 2016 Good morning Chair Murkowski, Ranking Member Cantwell and members of the committee. Thank you for the opportunity to testify about the FY 2017 budget and ongoing efforts of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). I’m John Vidale, a Professor at the University of Washington. As director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network and the Washington State seismologist, I’m privileged to work closely with the USGS to protect the public from earthquake and volcano hazards. The USGS performs yeoman service assessing and mitigating hazards from earthquakes, landslides and volcanic activity. The combination of universities and the USGS working together, exemplified by the seismic networks covering much of the country, which blend bleeding-edge research, operations, and deep outreach, have been supremely successful. For another example, in my home state of Washington, scientists use airborne laser mapping (also known as LiDAR) to find the locations of previously unknown active faults, slopes prone to destructive landslides, and downstream deposits of past eruptions of Cascade volcanoes. LiDAR mapping is critical to our understanding of natural hazards in the Pacific Northwest and across the Nation. I’ll focus here on new methods to reduce the risk from large earthquakes. A recent article in The New Yorker captured public attention with a nightmare scenario of an impending magnitude-9 earthquake on the Pacific Northwest coast, which has worried people across the entire Nation. -

Shakealert® Messaging Toolkit

For Emergency Managers and other Earthquake Preparedness Practitioners ShakeAlert® Messaging Toolkit December 2020 MESSAGING TOOLKIT TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Overview ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Core Messages ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Organization ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 How to Use the Messaging Toolkit ............................................................................................................................. 3 Icons as Visual Signposts ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Tools At-A-Glance ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Consistent Use of Materials and Messaging .............................................................................................................. 4 Tools At-a-Glance by Stakeholder Group .................................................................................................................. -

Quickstart Guide for Prospective Technical Partners (FINAL)

ShakeAlert Earthquake Early Warning System Technical Engagement Program California – Oregon – Washington Quickstart Guide for Prospective Technical Partners Last modified 4/01/21 Purpose of this Guide This Quickstart Guide is designed to inform prospective technical partners about the ShakeAlert® Earthquake Early Warning system as they decide whether to pursue a Technical Partnership with the USGS. This guide provides basic details about the flow of information from the USGS to technical partners, the contents of ShakeAlert Messages, and a list of considerations to help assess technical needs and requirements. Information Flow from the USGS to the Technical Partner USGS Role: The USGS and its university partners monitor ground shaking using an array of seismic sensors, and use this data to detect earthquakes and issue a variety of ShakeAlert Messages in XML, a structured plain text format. Technical Partner Role: Develop alert delivery and automated control solutions based on the ShakeAlert messages. As a Technical partner you will subscribe to USGS message brokers (“Alert Layer” ActiveMQ brokers) and listen continuously for ShakeAlert Messages. When you receive messages, you will use the ShakeAlert published shaking estimates to protect your clients or assets, by alerting people and/or initiating automated controls. Revised: 4/01/21 What is a ShakeAlert® Message? The USGS ShakeAlert system publishes ShakeAlert Messages in XML format on its alert servers. Messages contain estimated earthquake magnitude, location, and, for some message types, the areal distribution of expected shaking intensity levels. The first message of any type is labeled with a message-type of “new,” and updates (labeled with a message-type of “update”) follow rapidly as more information is processed and the earthquake grows.