Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prey Delivered to Roseate and Common Tern Chicks; Composition and Temporal Variability Carl Safina, Richard H

J. Field Ornithol., 61(3):331-338 PREY DELIVERED TO ROSEATE AND COMMON TERN CHICKS; COMPOSITION AND TEMPORAL VARIABILITY CARL SAFINA, RICHARD H. WAGNER1, DAVID A. WITTING 2, AND KELLYJ. SMITH2 National Audubon Society 306 South Bay Ave Islip, New York 11751 USA Abstract.--We observedprey deliveriesto Roseate(Sterna dougallii) and Common (S. hi- rundo)tern chicks.Roseate Terns were highly specializedand fed their chicksmostly sandeels (Ammodytesamericanus), whereas Common Terns delivered a diversity of prey. Species compositionof deliveredprey varied annually and weekly. Of four major prey species,the proportionof deliveriescontaining anchovies, juvenile bluefish, and herring varied with the time of morning, whereasthe proportionmade up of sandeelsremained generally constant. ENTREGA DE ALIMENTO A POLLUELOS DE STERNA DOUGALLH Y S. HIRUNDO: COMPOSICION Y VARIABILIDAD TEMPORAL Sinopsis.--Obscrvamosla cntregade alimentoa polluelosde Sternadougallii y S. hirundo. Los adultosdc S. dougalliialimcntaron a suspolluclos muy particularmentecon individuos dc Ammodytesamericanus, micntras quc la otra cspccicdc gaviotaalimcnt6 a suspichoncs con una gran divcrsidaddc prcsas.La composici6ndcl alimcntocntrcgado a los pichoncs, result6variable a travis de1cstudio. Dc las cuatrocspccics dc pcccsutilizadas principalmcntc comoalimcnto para lospichoncs, la proporci6ncntrcgada quc contcnlaanchoas, pcz azulado y arcncavari6 a travfisdc lashoras dc la mafiana,micntras quc la quc contcnlaA. americanus pcrmancci6gcncralmcntc constantc. Ever since Volterra (1931) -

The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding C.1625-1637

THE GOOD OLD WAY REVISITED: The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding c.1625-1637 Kate E. Riley, BA (Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia, School of Humanities, Discipline of History, 2007. ABSTRACT The Good Old Way Revisited: The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding c.1625-1637 The Ferrars are remembered as exemplars of Anglican piety. The London merchant family quit the city in 1625 and moved to the isolated manor of Little Gidding in Huntingdonshire. There they pursued a life of corporate devotion, supervised by the head of the household, Nicholas Ferrar, until he died in December 1637. To date, the life of the pious deacon Nicholas Ferrar has been the focus of histories of Little Gidding, which are conventionally hagiographical and give little consideration to the experiences of other members of the family, not least the many women in the household. Further, customary representations of the Ferrars have tended to remove them from their seventeenth-century context. Countering the biographical trend that has obscured many details of their communal life, this thesis provides a new, critical reading of the family’s years at Little Gidding while Nicholas Ferrar was alive. It examines the Ferrars in terms of their own time, as far as possible using contemporary documents instead of later accounts and confessional mythology. It shows that, while certain aspects of life at Little Gidding were unusual, on the whole the family was less exceptional than traditional histories have implied; certainly the family was not so unified and unworldly as the idealised images have suggested. -

Seabirds in Southeastern Hawaiian Waters

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 30, Number 1, 1999 SEABIRDS IN SOUTHEASTERN HAWAIIAN WATERS LARRY B. SPEAR and DAVID G. AINLEY, H. T. Harvey & Associates,P.O. Box 1180, Alviso, California 95002 PETER PYLE, Point Reyes Bird Observatory,4990 Shoreline Highway, Stinson Beach, California 94970 Waters within 200 nautical miles (370 km) of North America and the Hawaiian Archipelago(the exclusiveeconomic zone) are consideredas withinNorth Americanboundaries by birdrecords committees (e.g., Erickson and Terrill 1996). Seabirdswithin 370 km of the southern Hawaiian Islands (hereafterreferred to as Hawaiian waters)were studiedintensively by the PacificOcean BiologicalSurvey Program (POBSP) during 15 monthsin 1964 and 1965 (King 1970). Theseresearchers replicated a tracklineeach month and providedconsiderable information on the seasonaloccurrence and distributionof seabirds in these waters. The data were primarily qualitative,however, because the POBSP surveyswere not basedon a strip of defined width nor were raw counts corrected for bird movement relative to that of the ship(see Analyses). As a result,estimation of density(birds per unit area) was not possible. From 1984 to 1991, using a more rigoroussurvey protocol, we re- surveyedseabirds in the southeasternpart of the region (Figure1). In this paper we providenew informationon the occurrence,distribution, effect of oceanographicfactors, and behaviorof seabirdsin southeasternHawai- ian waters, includingdensity estimatesof abundant species. We also document the occurrenceof six speciesunrecorded or unconfirmed in thesewaters, the ParasiticJaeger (Stercorarius parasiticus), South Polar Skua (Catharacta maccormicki), Tahiti Petrel (Pterodroma rostrata), Herald Petrel (P. heraldica), Stejneger's Petrel (P. Iongirostris), and Pycroft'sPetrel (P. pycrofti). STUDY AREA AND SURVEY PROTOCOL Our studywas a piggybackproject conducted aboard vessels studying the physicaloceanography of the easterntropical Pacific. -

Tracking a Small Seabird: First Records of Foraging Movements in the Sooty Tern Onychoprion Fuscatus

Soanes et al.: Sooty Tern foraging movements 235 TRACKING A SMALL SEABIRD: FIRST RECORDS OF FORAGING MOVEMENTS IN THE SOOTY TERN ONYCHOPRION FUSCATUS LOUISE M. SOANES1,2,, JENNIFER A. BRIGHT3, GARY BRODIN4, FARAH MUKHIDA5 & JONATHAN A. GREEN1 1School of Environmental Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3GP, UK 2Department of Life Sciences, University of Roehampton, London SW15 4JD, UK ([email protected]) 3RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, The Lodge, Sandy SG19 2DL, UK 4Pathtrack Ltd., Otley, West Yorkshire LS21 3PB, UK 5Anguilla National Trust, The Valley, Anguilla, British West Indies Received 23 April 2015, accepted 10 August 2015 SUMMARY Soanes, L.M., BRIGHT, J.A., Brodin, G., mukhida, F. & GREEN, J.A. 2015. Tracking a small seabird: First records of foraging behaviour in the Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus. Marine Ornithology 43: 235–239. Over the last 12 years, the use of global positioning system (GPS) technology to track the movements of seabirds has revealed important information on their behaviour and ecology that has greatly aided in their conservation. To date, the main limiting factor in the tracking of seabirds has been the size of loggers, restricting their use to medium-sized or larger seabird species only. This study reports on the GPS tracking of a small seabird, the Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus, from the globally important population breeding on Dog Island, Anguilla. The eight Sooty Terns tracked in this preliminary study foraged a mean maximum distance of 94 (SE 12) km from the breeding colony, with a mean trip duration of 12 h 35 min, and mean travel speed of 14.8 (SE 1.2) km/h. -

A Record of Sooty Tern Onychoprion Fuscatus from Gujarat, India M

22 Indian BIRDS VOL. 10 NO. 1 (PUBL. 30 APRIL 2015) A record of Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus from Gujarat, India M. U. Jat & B. M. Parasharya Jat, M.U., & Parasharya, B. M., 2015. A record of Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus in Gujarat, India. Indian BIRDS 10 (1): 22-23. M. U. Jat, 3, Anand Colony, Poultry Farm Road, First Gate, Atul, Valsad, Gujarat, India. Email: [email protected] [MUJ] B. M. Parasharya, AINP on Agricultural Ornithology, Anand Agricultural University, Anand 388110, Gujarat, India. Email: [email protected] [BMP] Manuscript received on 18 March 2014. he Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus is a seabird of been rescued by Punit Patel at Khadki Village, near Pardi Town the tropical oceans that breeds on islands throughout (20.517°N, 72.933°E), Valsad District, in Gujarat. Khadki is seven Tthe equatorial zone. Within limits of the Indian kilometers east of the coast. The tern was feeble and unable Subcontinent, its race O. f. nubilosa is known to breed in to fly, though it would spread its wings when disturbed [18]. Lakshadweep on the Cherbaniani Reef, and the Pitti Islands, the The bird was photographed and its plumage described. It was Vengurla Rocks off the western coast of the Indian Peninsula, weighed and sexed the next day, when it died. Its morphometric north-western Sri Lanka, and, reportedly, in the Maldives (Ali & measurements (after Dhindsa & Sandhu 1984; Reynolds et al. Ripley 1981; Pande et al. 2007; Rasmussen & Anderton 2012). 2008) were taken using ruled scale, divider, and digital vernier Storm blown vagrants have occurred far inland (Ali & Ripley calipers to the nearest 0.1 mm. -

Environmental Impacts on the Success of Bermuda's Inhabitants Alyssa V

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2016 Environmental Impacts on the Success of Bermuda's Inhabitants Alyssa V. Pietraszek University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Recommended Citation Pietraszek, Alyssa V., "Environmental Impacts on the Success of Bermuda's Inhabitants" (2016). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 493. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/493http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/493 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Page 1 Introduction. Since the discovery of the island in 1505, the lifestyle of the inhabitants of Bermuda has been influenced by the island’s isolated geographic location and distinctive geological setting. This influence is visible in nearly every aspect of Bermudian society, from the adoption of small- scale adjustments, such as the collection of rainwater as a source of freshwater and the utilization of fishing wells, to large-scale modifications, such as the development of a maritime economy and the reliance on tourism and international finances. These accommodations are the direct consequences of Bermuda’s environmental and geographic setting and are necessary for Bermudians to survive and prosper on the island. Geographic, Climatic, and Geological Setting. Bermuda is located in the North Atlantic Ocean at 32º 20’ N, 64º 45’ W, northwest of the Sargasso Sea and around 1000 kilometers southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Vacher & Rowe, 1997). -

Bridled Tern Breeding Record in the United States

SCIENCE areamore closely, and quickly locat- ed a downy Bridled Tern chick crouched under one of the rocks which was usedas a perchby the BRIDLEDTERN adult. We have accumulated addi- tionalrecords of nestingat thissite in subsequentyears. BREEDING BridledTerns breed throughout the Bahamas and the Greater and LesserAntilles, and occur commonly offshoreFlorida and regularlyoff RECORDIN THE other southeasternstates, but this is thefirst evidence of breedingreport- edfor NorthAmerica north of Quin- UNITEDSTATES tana Roo on the Yucatan Peninsula (Howell et al. i99o). In this note we describe the islet, the Roseate Tern colony,and the BridledTern nest byPyne Hoffman, site,and compare the nesting habitat of these terns to that used in the Ba- AlexanderSprunt IV, hamas. The FloridaKeys are flankedto PeterKalla, and Mark Robson the eastand south by a line of coral reefsparalleling the main keysat a distance of 6 to i2 kilometers. The best-developed(and some of the On themorning of July •5, •987, two Terns(Sterna anaethetus) flying low shallowest)reefs occur along the reef of us(Sprunt and Hoffman) visited a overthe colony.One of theseterns margin,adjacent to thedeep water of RoseateTern (Sterna dougallih colony sat for extendedperiods on coral the FloridaStraits. The tern colony on a small coral rubble islet on Peli- rocksin the northeasternpart of the occupiesan isletof approximately canShoal, south of BocaChica Key, isletand circled, calling softly when one-fourthhectare composed of coral MonroeCounty, Florida. During in- we approached.We returnedto the rubble and sand located on a shallow spectionwe observedfour Bridled island that afternoon to examine the sectionof the fringingreef called Bridled Tern on Pelican Shoal. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Copyrighted Material

16_962244 bindex.qxp 8/1/06 3:44 PM Page 232 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX resort hotels, 72–73, 76 Annapolis-Bermuda Race, 159 small hotels, 81–82 Antiques, City of Hamilton, 200 surfing for, 37 Apartments, 70, 92 AARP, 36 types of, 69–70 Archie Brown (City of Above and Beyond Tours, 35 Warwick Parish Hamilton), 207 Access-Able Travel Source, 34 guesthouse, 99–100 Architectural highlights, Access America, 31 housekeeping units, 161–162 Accessible Journeys, 34 91–92, 93–94 Architecture, 226–227 Accommodations, 69–100. See what’s new in, 2 Art, 229–230 also Accommodations Index Addresses, finding, 53 Art and Architecture Walk, 166 best bargains, 16 Admiralty House Park (Pem- Art galleries best places to stay with the broke Parish), 173 Bermuda Arts Centre (Sandys kids, 15–16 African American Association of Parish), 168–169 best resorts for lovers and Innkeepers International, 37 City of Hamilton, 200 honeymooners, 14–15 African-American travelers, Paget Parish, 209 dining at your hotel, 71 36–37 Southampton Parish, 208 family-friendly, 89 African Diaspora Heritage A. S. Cooper & Sons (City of guesthouses, 96–100 Trail, 175 Hamilton), 202 Hamilton Parish, resort hotels, After Hours (Paget Parish), 210 Aston & Gunn (City of 79–81 Afternoon tea, 102 Hamilton), 202 landing the best room, 72 Agriculture Exhibit (Paget), 28 Astwood Cove (Warwick Paget Parish AirAmbulanceCard.com, 35 Parish), 4, 140–141 cottage colony, 87 Air Canada, 40 Astwood Dickinson (City guesthouses, 97, 98 Airfares of Hamilton), -

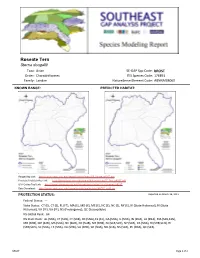

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Brost Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae Natureserve Element Code: ABNNM08060

Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bROST Order: Charadriiformes ITIS Species Code: 176891 Family: Laridae NatureServe Element Code: ABNNM08060 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bROST.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bROST.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bROST Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bROST_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (E), CT (E), FL (FT), MA (E), MD (X), ME (E), NC (E), NC (E), NY (E), RI (State Historical), RI (State Historical), VA (LE), VA (LE), NS (Endangered), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G4 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), CT (S1B), CT (S1B), DE (SNA), FL (S1), GA (SNA), IL (SNA), IN (SNA), LA (SNA), MA (S2B,S3N), MD (SHB), ME (S2B), MS (SNA), NC (SUB), NC (SUB), NH (SHB), NJ (S1B,S1N), NY (S1B), PA (SNA), RI (SHB,S1N), RI (SHB,S1N), SC (SNA), TX (SNA), VA (SHB), VA (SHB), WI (SNA), NB (S1B), NS (S1B), PE (SNA), QC (S1B) bROST Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 1,143.7 16 0.0 0 0.0 0 291.4 4 US Dept. -

SOOTY-TERN-SAP-Edited

Photo: D. Fox SUMMARY Taxonomy: Kingdom: Animalia; Phylum: Chordata; Class: Aves; Order: Charadriiformes; Family: Laridae; Species: Onychoprion fuscatus Native, breeding Nativeness: Description: Medium-sized, highly pelagic seabird with contrasting black and white plumage and a distinctive ‘wideawake’ call. Extremely sociable, forming very large nesting colonies on open ground. Diet consists predominantly of small fish and squid picked from the surface of ocean. Almost always feeds in association with sub-surface predators such as tuna and dolphins which drive prey within reach. IUCN Red List status: Least concern Local trend: Stable Threats: The major threats to sooty terns are overfishing of tuna and invasive alien species; secondary threats include climate change-induced habitat alteration. Citation: Ascension Island Government (2015) Sooty tern species action plan. In: The Ascension Island Biodiversity Action Plan. Ascension Island Government Conservation Department, Georgetown, Ascension Island Ascension Island BAP: Onychoprion fuscatas 2 Distribution Global Sooty terns are widespread, pan-tropical seabirds ranging across much of the tropical and sub-tropical Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. They typically nest on isolated, oceanic islands. Major Atlantic nesting colonies (>50,000 pairs) include Atol das Rocas (Brazil) (approx. 70,000 pairs [1]), the Tinhosas Islands (Sao Tome & Principe) (approx. 100,000-160,000 pairs; [2,3]), the Dominican Republic (approx. 80,000 pairs;[4]), Anguilla (UK) ([5]) and Ascension Island (approx. 200,000 pairs; [6]). Local Nesting: The vast majority of sooty tern nesting currently occurs on the coastal plain at the south- west corner of the Island, known locally as the “Wideawake Fairs”. Two main sub-colonies can be distinguished, one at Mars Bay and the other at Waterside Fairs, although their footprints vary among breeding seasons (Figure 1; [6]). -

Key Administrative Decisions in the History of the Seventh-Day Adventist Education in Bermuda

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 1998 Key Administrative Decisions in the History of the Seventh-day Adventist Education in Bermuda Leslie C. Holder Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Holder, Leslie C., "Key Administrative Decisions in the History of the Seventh-day Adventist Education in Bermuda" (1998). Dissertations. 445. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/445 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted.