Review: He's the Shit by Ben Davis Artnet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piero Manzoni ‘Materials of His Time’ and ‘Lines’

Press Release Piero Manzoni ‘Materials of His Time’ and ‘Lines’ Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street 25 April – 26 July 2019 Opening reception: Thursday 25 April, 6 – 8 pm New York... Hauser & Wirth is pleased to present two concurrent exhibitions devoted to Piero Manzoni, a seminal figure of postwar Italian Art and progenitor of Conceptualism. During a brief but influential career that ended upon his untimely death in 1963, Manzoni evolved from a self-taught abstract painter into an artistic disruptor. Curated by Rosalia Pasqualino di Marineo, director of the Piero Manzoni Foundation in Milan, the exhibitions ‘Piero Manzoni. Materials of His Time’ and ‘Piero Manzoni. Lines’ unfold over two floors and focus on Manzoni’s most significant bodies of work: his Achromes (paintings without color) and Linee (Lines) series. On view in the second floor gallery, ‘Materials of His Time’ features more than 70 of Manzoni’s radical Achromes and surveys the artist’s revolutionary approach to unconventional materials, such as sewn cloth, cotton balls, fiberglass, bread rolls, synthetic and natural fur, straw, cobalt chloride, polystyrene, stones, and more. Travelling from Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, the exhibition situates Manzoni as a peer of such artists as Lucio Fontana and Yves Klein, whose experiments continue to influence contemporary art-making today. ‘Materials of His Time’ also presents, for the first time in New York, the items on a wish list Manzoni outlined in a 1961 letter to his friend Henk Peeters: a room all in white fur, and another coated in fluorescent paint, totally immersing the visitor in white light. -

Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera Turin, 31 October 2017 – 20 January 2018

works by Pier Paolo Calzolari, Joseph Kosuth, Mario Merz, Emilio Prini Text by Cornelia Lauf Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera Turin, 31 October 2017 – 20 January 2018 Colour in Contextual Play An Installation by Joseph Kosuth Works by Enrico Castellani, Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, Joseph Kosuth, Piero Manzoni Curated by Cornelia Lauf Neon in Contextual Play Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera Works by Pier Paolo Calzolari, Joseph Kosuth, Mario Merz, Emilio Prini Text by Cornelia Lauf 31 October 2017 – 20 January 2018 Private View: 30 October 2017, 6 – 8 pm MAZZOLENI TURIN is proud to present a double project with American conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945), opening in October at its exhibition space in Piazza Solferino. Colour in Contextual Play. An Installation by Joseph Kosuth, curated by Cornelia Lauf, exhibited last Spring in the London premises of the gallery to international acclaim, includes works by Enrico Castellani (b. 1930), Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), Yves Klein (1928–1963), Piero Manzoni (1933– 1963), and Kosuth himself. This project, installed in the historic piano nobile rooms of Mazzoleni Turin, runs concurrently with a new exhibition, Neon in Contextual Play: Joseph Kosuth and Arte Povera devised especially for Mazzoleni Turin and installed in the groundfloor space, is focused on the use of Neon in the work of Joseph Kosuth and selected Arte Povera artists Mario Merz (1925-2003), Pier Paolo Calzolari (b. 1943) and Emilio Prini (1943-2016). Colour in Contextual Play juxtaposes monochrome works by Castellani, Fontana, Klein and Manzoni with works from Kosuth’s 1968 series ‘Art as Idea as Idea’. -

Download Press Release

THE MAYOR GALLERY 21 Cork Street, First Floor, London W1S 3LZ T +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 www.mayorgallery.com JOSIP VANIŠTA (1924 – 2018 Croatia) The Horizontal Line 30 October – 29 November 2019 White Line on a Black Surface 1968, oil and acrylic on canvas, 100 x 130 cm At the beginning of the 1960s, a group of renowned artists was formed in Zagreb under the name Gorgona and its manifesto was published in 1961. Active from 1959 to 1966 Gorgona’s members were the painters Josip Vaništa, Julije Knifer, Marijan Jevšovar and Duro Seder, the sculptor Ivan Kožarić and the architect Miljenko Horvat, as well as the art historians and critics Radoslav Putar, Matko Meštrović and Dimitrije Bašičević. Gorgona strived towards further subversive action on all artistic fronts. Throughout the group’s work, which was not primarily focused on painting, but on ‘art as a sum of possible interpretations’, there is an evident Dadaist genesis of ideas and theoretical principles, with the aim of infiltrating art into all aspects of the socialist society of the period in the manner of Fluxus. They continuously worked towards achieving ‘a space of exercised freedom’ (Mira Gattin) by using humour, the grotesque, irony, wit and paradox, as well as by embracing the philosophy of absurdism. Of all the painting innovations introduced by the group members in the 1960s, Josip Vaništa’s concept of a single horizontal line flowing through the middle of a monochrome canvas represents the most radical summation of Gorgona’s activities and aims. According to the theorist Mira Gattin, whose work focused on the group, the concept struggles ‘with the fact that the art has been brought to the edge of existence and silence, but still contains a trace of romanticist nostalgia that brings it back from nothingness, in the context of anticipatory aesthetic categories.’ Between 1963 and 1965, Vaništa created a series of paintings consisting of a straight line crossing a monochrome surface. -

Ebook Download Piero Manzoni : When Bodies Became Art Kindle

PIERO MANZONI : WHEN BODIES BECAME ART PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Engler | 264 pages | 31 Oct 2013 | Kerber Verlag | 9783866788749 | English | Bielefeld, Germany Piero Manzoni : When Bodies Became Art PDF Book The shredded canvas was itself a copy of an image spray-painted on a London wall. To some extent, this is indeed an event that continues to unfold until this day, as a recurring question, as the catalyst of a discussion between the object, the community of artists, and the public. In April , in Rome, in a manifestation at the Galleria La Tartaruga, Piero Manzoni began to sign people nude models or visitors changing them into works of art. New Hardcover Quantity available: 1. As an artwork, the interaction between people is where the art lies, rather than in an object. Save as PDF. Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? Manzoni metaphorically transformed the basest — excrements- into gold; not through any transmutation but through the art market, by succeeding to inject the aura of an unrepeatable event into an object. Piero Manzoni , , p. Photo: Antonio Maniscalco. Buy New Learn more about this copy. Original title Merda d'artista. Updated and modified regularly [Accessed ] Copy to clipboard. Site web. A red stamp certified that the subject was a whole work of art for life. This would however be superficial, if left at that. But this is not certain until tested. Cite article. View all copies of this ISBN edition:. Condition: new. Few artists have combined conceptual ingenuity with devastating critique as deftly and wittily as Piero Manzoni — Glory, epics, the greatest narratives of human history, made present at least to some degree. -

La Libertá O Morte Freedom Or Death

Herning Museum of Contemporary Art: ‘La liberta o morte’, 2009 la libertá o morte freedom or death By Jannis Kounellis HEART Herning Museum of Contemporary Art opens its doors for the first time to present a retrospective exhibition of the works of the Italian artist Jannis Kounellis (B. 1936). This is the first major presentation of Kounelli’s works in Scandinavia, and the artist will create a number of new works for the exhibition. HEART owns the world’s largest collection of works by the Italian artist Piero Manzoni. In his early works from © AL the 1950s and 1960s Kounellis may well have been the D EN D one young artist whose sensibilities and choice of YL materials came closest to those of Manzoni. G TEEN : S : OTO F Untitled, 1993. Old seals and ropes. Variable dimensions HEART / HERNING MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART / JANNIS KOUNELLIS la libertá o morte freedom or death Freedom or death The HEART exhibition of Jannis Kounellis’ work derives its With its text, Untitled 1969 refers to the French Revolution and title from a piece created in 1969. Strictly speaking, the to two of the strongest champions of the Revolution. Marat title of the object is not even La Liberta o Morte. Like most and Robespierre both fell victim to their own fanaticism, but of Kounelli’s work the piece in question has no title, but the during their brief careers they also laid down the foundations statement or exclamation is the very essence of the work. of the ideals of freedom inherent within Western European Untitled, 1969 consists of a sheet of iron with dimensions democracy. -

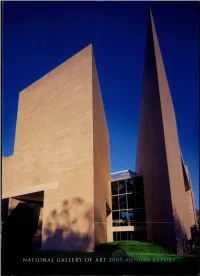

Annual Report 2005

NATIONAL GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES (as of 30 September 2005) Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine Chairman Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Robert F. Erburu Heidi L. Berry John C. Fontaine W. Russell G. Byers, Jr. Sharon P. Rockefeller Melvin S. Cohen John Wilmerding Edwin L. Cox Robert W. Duemling James T. Dyke Victoria P. Sant Barney A. Ebsworth Chairman Mark D. Ein John W. Snow Gregory W. Fazakerley Secretary of the Treasury Doris Fisher Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Robert F. Erburu Aaron I. Fleischman Chairman President John C. Fontaine Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller John Freidenrich John Wilmerding Marina K. French Morton Funger Lenore Greenberg Robert F. Erburu Rose Ellen Meyerhoff Greene Chairman Richard C. Hedreen John W. Snow Eric H. Holder, Jr. Secretary of the Treasury Victoria P. Sant Robert J. Hurst Alberto Ibarguen John C. Fontaine Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Linda H. Kaufman John Wilmerding James V. Kimsey Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Ruth Carter Stevenson Leonard A. Lauder Alexander M. Laughlin Alexander M. Laughlin Robert H. Smith LaSalle D. Leffall Julian Ganz, Jr. Joyce Menschel David O. Maxwell Harvey S. Shipley Miller Diane A. Nixon John Wilmerding John G. Roberts, Jr. John G. Pappajohn Chief Justice of the Victoria P. Sant United States President Sally Engelhard Pingree Earl A. Powell III Diana Prince Director Mitchell P. Rales Alan Shestack Catherine B. Reynolds Deputy Director David M. Rubenstein Elizabeth Cropper RogerW. Sant Dean, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts B. Francis Saul II Darrell R. Willson Thomas A. -

Alberto Burri: the Art of the Matter

Alberto Burri: The Art of the Matter Judith Rozner A thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Volume I – Text Volume II - Illustration March 2015 School of Culture and Communication. The University of Melbourne. Produced on archival quality paper i VOLUME I ii For Avraham and Malka Ur iii iv ABSTRACT "Alberto Burri, an Italian artist of the immediate post WWII period, introduced common, everyday materials into his art. In so doing material became both the subject of his work as well as the object out of which the work was made. This thesis argues that the primary purpose of Burri's work throughout his career was to provoke a tactile, sensuous response in the viewer, a response which can best be understood through the lens of phenomenology." v vi DECLARATION This is to certify that: I. The thesis comprises only my original work. II. Due acknowledgment has been made in the text to all other material used. III. The thesis is less than 100.000 words in length exclusive of tables, maps, bibliography and appendices. Judith Rozner vii viii Preface In 1999, following an introduction by a mutual friend, I was invited by Minsa Craig- Burri, the widow of the artist Alberto Burri, to help her compile a biography of her life with her husband.1 I stayed and worked on the manuscript at their home at 59, Blvd. Eduard VII, in Beaulieu-sur-Mar, in the South of France for about six weeks. I had not seen the artist’s work before my arrival, and on my first encounter with it I just shrugged my shoulders and raised my eyebrows at the high prices it commanded in the market. -

Carte Italiane, Vol

Italian Art circa 1968: Continuities and Generational Shifts^ Adrian R. Diinin Mciìipliis Coìh'iic o/Art Nineteen sixty-eight has long beei) heralded as a, it not tlic, pivotal moment of the post-World War II decades. Following the assassina- tions of Malcolm X and both Kennedys, the erection of the Beriin Wall, the war in Vietnam, the first manned space flights, the Second Viitican Council and the invasion of technology throughout Europe, that single year was perhaps the most powerful and tectonic paradigm shift of the many that the decade already had witnessed. The student uprisings in Paris, the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the invasion of Prague by Wirsaw Pact troops ali exacerbated what had been a markedly violent period, quelling the optimism that had markcd much of the decade and setting the tone for the coming malaise ot the 1970s. Italy, too, was participant in these epochal events, albeit in a sonie- what different nianner. Its students' uprisings began slightly earlier than those of France; the occupation of the University ofTrento took place in the autumn ot l*-'67. These were followed by workers' protests, with massive strikes in the first half of the year. However, the national elec- tions ot 1968 diverted much attention, and uniquely peculiar events, including the June 10''' European Championship victory overYugoslavia (2-0) and the declaration of the Republic of Rose Island off of the coast ot Rimini, made for a varied experience. Artistically, 1968 saw Italy peering across new, unexplored ter- rain. Over the course ot the prcvious few years, a group of exhibitions throughout the country began introducing those who would soon he known as (irte povcni.- The nomenclature itself was debuted at the September 1967 "Arte povera - Im spazio" exhibition held at Genoa s La Bertesca gallery, though its protagonists held noteworthy shows atTurin's Sperone gallery and Rome's L'Attico in the years preceding. -

Marshall Plan Modernism Italian Postwar

MARSHALL PLAN MODERNISM ITALIAN POSTWAR ABSTRACTION AND THE BEGINNINGS OF AUTONOMIA JALEH MANSOOR JALEH MANSOOR MARSHALL PLAN MODERNISM ITALIAN POSTWAR ABSTRACTION AND THE BEGINNINGS OF AUTONOMIA Duke University Press Durham and London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Interior design by Mindy Basinger Hill; cover design by Heather Hensley Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Mansoor, Jaleh, [date] author. Title: Marshall Plan modernism : Italian postwar abstraction and the beginnings of autonomia / Jaleh Mansoor. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2016019790 (print) | lccn 2016018394 (ebook) isbn 9780822362456 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362609 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373681 (e-book) Subjects: lcsh: Art, Italian—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—Italy. | Art, Abstract—Italy. Classification: lcc n6918 (print) | lcc n6918 .m288 2016 (ebook) | ddc 700.94509/04—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019790 Cover Art: Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attese, © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ars), New York / siae, Rome This book was made possible by a collaborative grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii INTRODUCTION Labor, (Workers’) Autonomy, -

The Making of Manzoni

The making of Manzoni The playful and provocative Italian artist Piero Manzoni, a pioneer of conceptualism, created some of his most significant work in Denmark, where a local shirt-factory owner used art to put the town of Herning on the map – and left an extraordinary museum as his legacy By Harry Pearson. Photographs by Jan Søndergaard The Steven Holl-designed building that is home to HEART Herning Museum of Modern Art [ 000 ] [ 000 ] [ SECTIONS ] Left, Piero Manzoni Manzoni in the archives with one of his ‘living at HEART: three of sculptures’, a seamstress his Achrome works from the Black Factory. executed in 1961; and a Opposite, works by painting, Impronte, 1961 It didn’t end there. In the Angli factory the rapid rattle of sewing machines was drowned out by the sound of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and other giants of modern jazz, whose dissonant improvisations pumped from the speakers throughout the working day. Despite appearances, Angli was not a fashion house. Its wares were sold in department stores. There was nothing cutting-edge or avant-garde about the designs. Aage Damgaard was no Walter Van Beirendonck or Dries Van Noten. This was not a swinging Yves Saint Laurent hanging out with Andy Warhol and his Factory cohorts on the Left Bank. No, the shirtmaker’s association with Gadegaard, the relationship that brought Manzoni, and later Enrico Castellani, to this unsung corner of Scandinavia was something far more singular and surprising. ‘The 1950s were a time of sweeping social change in Denmark,’ explains Holger Reenberg, director of HEART, the Herning Museum of Contemporary Art. -

From the Roll to the Infinite Painting 191

188 Claire Smith 11 Print, Picture and Sequence (London: Bloomsbury, 2010), p. 164. 21. See Tom Gunning, Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity (London: BFI, 2000) 22. Tomasovic, ‘The Hollywood Cobweb’, p. 311. 23. Tomasovic, ‘The Hollywood Cobweb’, p. 311. 24. Janice Norwood, ‘Visual Culture and the Repertoire of a Popular East-End Theatre’, in A. Heinrich, K. Newey, and J Richards (eds), Ruskin, the Theatre and Victorian Visual Culture (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), p. 135. 25. Norwood, ‘A Popular East-End Theatre’, p. 135. 26. Laurent Guido, ‘Rhythmic Bodies/Movies: Dance as Attraction in Early Film Culture’, in Strauven, Cinema of Attractions, p. 139. 27. Guido, ‘Rhythmic Bodies/Movies’, p.143. With roots in the magical colours, mechanical trickery and dance-like movements of the feerie plays of the nineteenth century, these films often display their theatrical provenance through the lively choreography of sets, costumes and the human form. See for example The Frog (1908), The Spring Fairy (1902), The King- dom of the Fairies (1903), Modern Sculptors (1908). 28. Guido, ‘Rhythmic Bodies/Movies’, p.143. 29. Although not possible to discuss in detail within the parameters of this chapter, blockbusters exploiting dance as spectacle enjoyed significant box office success in this decade, Piero Manzoni’s from Fame (1980) to Footloose (1984), Flashdance (1983) to Dirty Dancing (1987), arguably signaling a return to exhibitio- nist practices around the choreography of the human form. 30. For an overview of the transformational role of the Ballet Russes see Jane Pritchard, Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–29 (London: V&A, 2011). -

Mazzoleni at Art Basel Piero Manzoni: Achromes / Linee 15 – 18 June 2017 Booth C8

Press Release Mazzoleni at Art Basel Piero Manzoni: Achromes / Linee 15 – 18 June 2017 Booth C8 Mazzoleni is pleased to announce its participation in Art Basel’s European edition for the first time this June with a solo presentation of Piero Manzoni (1933–1963) in the Feature sector of the fair. Manzoni is widely considered one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Known for his ironic and playful methodology, he radically transformed the artistic language of European art and developed a lasting reputation for prefiguring the Conceptual Art movement, among others. This exhibition will show examples from two of the artist’s most well known series of works, the Achromes (1955–1963) and the Linee (1959–1963). It follows the gallery’s acclaimed 2016 exhibition of the artist at its London space, ‘PIERO MANZONI Achromes: Linea Infinita’, which was the first exhibition to focus uniquely on the relationship between these two bodies of work. Bringing Achromes and Linee works into dialogue once more at Art Basel will allow Mazzoleni to continue the conversation around Manzoni’s fascination with the ‘infinite’, an idea conceptually explored by both series. From 1959 Manzoni focused entirely on attempting to manifest the infinite in his work, saying in his 1960 text Free Dimension that, ‘this indefinite surface, uniquely alive, even if in its material contingency cannot be infinite is, however, infinitable, infinitely repeatable, without a resolution to its continuity.’ The Linee were the first three-dimensional works Manzoni produced and therefore his first escape from the two-dimensional medium of painting he and his contemporaries found so restrictive and outmoded.