'Belisama and Her Daughters'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspinall Arms Walks with Taste

THE ASPINALL ARMS AND THE RIBBLE VALLEY WALKS with in Ribble Valley Grid Reference SD 7168638516 Livestock will be grazing in most of the fields, so keep Distance: 3 miles/4.8 km Time: 1½ hours Moderate: steep climbs and steps. THE ASPINALL ARMS The Aspinall Arms is a 19th Century coaching Inn, that sits on the banks of the River Ribble, overlooking the All Hallows’ Medieval Church and Great Mitton Hall on a raised blu½ opposite. Open fires, wooden floors, old style furniture and traditional rugs, the Aspinall Arms pub is brimming with character, warmth and most importantly, a great atmosphere. In such a welcoming environment with many friendly faces, you will certainly be made to feel entirely at home here and will get the urge to head back again and again. The Aspinall is the perfect place to relax and unwind, whether that is by the roaring fire on a large cosy chair, or in the substantial light-filled garden room, enjoying the wonderful views that overlook the terraced and landscaped riverside gardens. With plenty of space outdoors, this is another perfect spot to relax and enjoy the wonderful fresh country air, whilst enjoying a spot of lunch and a refreshing drink! Sitting at the heart of the building is the central bar, which has six cask ales on tap, a back shelf crammed with malts, a great selection of gins and wines, an open fire and a stone flagged floor, so that walkers, cyclists and dogs will be made to feel at home. Mitton Rd, Mitton, Clitheroe, Lancashire BB7 9PQ Tel: 01254 826 555 | www.aspinallarmspub.co.uk In order to avoid disappointment, when planning to enjoy this walk with taste experience, it is recommended that you check opening times and availability of the venue in advance. -

Construction Traffic Management Plan

Haweswater Aqueduct Resilience Programme Construction Traffic Management Plan Proposed Marl Hill and Bowland Sections Access to Bonstone, Braddup and Newton-in-Bowland compounds Option 1 - Use of the Existing Ribble Crossings Project No: 80061155 Projectwise Ref: 80061155-01-UU-TR4-XX-RP-C-00012 Planning Ref: RVBC-MH-APP-007_01 Version Purpose / summary of Date Written By Checked By Approved By changes 0.1 02.02.21 TR - - P01 07.04.21 TR WB ON 0.2 For planning submission 14.06.21 AS WB ON Copyright © United Utilities Water Limited 2020 1 Haweswater Aqueduct Resilience Programme Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1.1 The Haweswater Aqueduct ......................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 The Bowland Section .................................................................................................. 4 1.1.3 The Marl Hill Section................................................................................................... 4 1.1.4 Shared access ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Purpose of the Document .................................................................................................. 4 2. Sequencing of proposed works and anticipated -

North West Water Authority

South Lancashire Fisheries Advisory Committee 30th June, 1976. Item Type monograph Publisher North West Water Authority Download date 29/09/2021 05:33:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/27037 North W est Water Authority Dawson House, Great Sankey Warrington WA5 3LW Telephone Penketh 4321 23rd June, 1976. TO: Members of the South Lancashire Fisheries Advisory Committee. (Messrs. R.D. Houghton (Chairman); T.A.F. Barnes; T.A. Blackledge; R. Farrington; J. Johnson; R.H. Wiseman; Dr. R.B. Broughton; Professor W.E. Kershaw; and the Chairman of the Authority (P.J. Liddell); The Vice-Chairman of the Authority (J.A. Foster); and the Chairman of the Regional Fisheries Advisory Committee (J.R.S. Watson)(ex officio). Dear Sir, A meeting of the SOUTH LANCASHIRE FISHERIES ADVISORY COMMITTEE will be held at 2.30 p.m. on WEDNESDAY 30TH JUNE, 1976, at the LANCASHIRE AREA OFFICE OF THE RIVERS DIVISION, 48 WEST CLIFF, PRESTON for the consideration of the following business. Yours faithfully, G.W. SHAW, Director of Administration. AGENDA 1. Apologies for absence. 2. Minutes of the last meeting (previously circulated). 3. Mitton Fishery. 4. Fisheries in the ownership of the Authority. 5. Report by Area Fisheries Officer on Fisheries Activities. 6. Pollution of Trawden Water and Colne Water - Bairdtex Ltd. 7. Seminar on water conditions dangerous to fish life. 8. Calendar of meetings 1976/77. 9. Any other business. 3 NORTH WEST WATER AUTHORITY SOUTH LANCASHIRE FISHERIES ADVISORY COMMITTEE 30TH JUNE, 1976 MITTON FISHERY 1. At the last meeting of the Regional Committee on 3rd May, a report was submitted regarding the claim of the Trustees of Stonyhurst College to the ownership of the whole of the bed of the Rivers Hodder find Ribble, insofar as the same are co- extensive with the former Manor of Aighton. -

Conservation Area Appraisals

Ribble Valley Borough Council - Chatburn Conservation Area Appraisal 1 _____________________________________________________________________ CHATBURN CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL This document has been written and produced by The Conservation Studio, 1 Querns Lane, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 1RL Final revision 25.10.05/ photos added 18.12.06 The Conservation Studio 2005 Ribble Valley Borough Council - Chatburn Conservation Area Appraisal 2 _____________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Introduction Purpose of the appraisal Summary of special interest The planning policy context Local planning policy Location and setting Location and context General character and plan form Landscape setting Topography, geology, relationship of the conservation area to its surroundings Historic development and archaeology Origins and historic development Spatial analysis Key views and vistas The character of spaces within the area Definition of the special interest of the conservation area Activities/uses Plan form and building types Architectural qualities Listed buildings Buildings of Townscape Merit Local details Green spaces, trees and other natural elements Issues Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities Threats Recommendations Conservation Area boundary review Article 4 Direction Monitoring and review Bibliography The Conservation Studio 2005 Ribble Valley Borough Council - Chatburn Conservation Area Appraisal 3 _____________________________________________________________________ CHATBURN CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Introduction Purpose of the appraisal This appraisal seeks to record and analyse the various features that give the Chatburn Conservation Area its special architectural and historic interest. The area’s buildings and spaces are noted and described, and marked on the Townscape Appraisal Map along with significant trees, surviving historic paving, and important views into and out of the conservation area. There is a presumption that all of these features should be “preserved or enhanced”, as required by the legislation. -

Winckley Square Around Here’ the Geography Is Key to the History Walton

Replica of the ceremonial Roman cavalry helmet (c100 A.D.) The last battle fought on English soil was the battle of Preston in unchallenged across the bridge and began to surround Preston discovered at Ribchester in 1796: photo Steve Harrison 1715. Jacobites (the word comes from the Latin for James- town centre. The battle that followed resulted in far more Jacobus) were the supporters of James, the Old Pretender; son Government deaths than of Jacobites but led ultimately to the of the deposed James II. They wanted to see the Stuart line surrender of the supporters of James. It was recorded at the time ‘Not much history restored in place of the Protestant George I. that the Jacobite Gentlemen Ocers, having declared James the King in Preston Market Square, spent the next few days The Jacobites occupied Preston in November 1715. Meanwhile celebrating and drinking; enchanted by the beauty of the the Government forces marched from the south and east to women of Preston. Having married a beautiful woman I met in a By Steve Harrison: Preston. The Jacobites made no attempt to block the bridge at Preston pub, not far from the same market square, I know the Friend of Winckley Square around here’ The Geography is key to the History Walton. The Government forces of George I marched feeling. The Ribble Valley acts both as a route and as a barrier. St What is apparent to the Friends of Winckley Square (FoWS) is that every aspect of the Leonard’s is built on top of the millstone grit hill which stands between the Rivers Ribble and Darwen. -

Central Lancashire Open Space Assessment Report

CENTRAL LANCASHIRE OPEN SPACE ASSESSMENT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019 Knight, Kavanagh & Page Ltd Company No: 9145032 (England) MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Registered Office: 1 -2 Frecheville Court, off Knowsley Street, Bury BL9 0UF T: 0161 764 7040 E: [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk Quality assurance Name Date Report origination AL / CD July 2018 Quality control CMF July 2018 Client comments Various Sept/Oct/Nov/Dec 2018 Revised version KKP February 2019 Agreed sign off April 2019 Contents PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Report structure ...................................................................................................... 2 1.2 National context ...................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Local context ........................................................................................................... 3 PART 2: METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Analysis area and population .................................................................................. 4 2.2 Auditing local provision (supply) .............................................................................. 6 2.3 Quality and value .................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Quality and value thresholds .................................................................................. -

Summary of Fisheries Statistics 1985

DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING & ENGINEERING. SUMMARY OF FISHERIES STATISTICS 1985. ISSN 0144-9141 SUMMARY OF FISHERIES STATISTICS, 1985 CONTENTS 1. Catch Statistics 1.1 Rod and line catches (from licence returns) 1.1.1 Salmon 1.1.2 Migratory Trout 1.2 Commercial catches 1.2.1 Salmon 1.2.2 Migratory Trout 2. Fish Culture and Hatchery Operations 2.1 Brood fish collection 2.2 Hatchery operations and salmon and sea trout stocking 2.2.1 Holmwrangle Hatchery 2.2.1.1 Numbers of ova laid down 2.2.1.2 Salmon and sea trout planting 2.2.2 Middleton Hatchery 2.2.2.1 Numbers of ova laid down 2.2.2.2 Salmon, and sea trout planting 2.2.3 Langcliffe Hatchery 2.2.3.1 Numbers of ova laid down 2.2.3.2 Salmon and sea trout planting - 1 - 3. Restocking with Trout and Freshwater Fish 3.1 Non-migratory trout 3.1.1 Stocking by Angling Associations etc., and Fish Farms 3.1.2 Stocking by NWWA 3.1.2.1 North Cumbria 3.1.2.2 South Cumbria/North Lancashire 3.1.2.3 South Lancashire 3.1.2.4 Mersey and Weaver 3.2 Freshwater Fish 3.2.1 Stocking by Angling Associations, etc 3.2.2 Fish transfers carried out by N.W.W.A. 3.2.2.1 Northern Area 3.2.2.2 Southern Area - South Lancashire 3.2.2.3 Southern Area - Mersey and Weaver 4. Fish Movement Recorded at Authority Fish Counters 4.1 River Lune 4.2 River Kent 4.3 River Leven 4.4 River Duddon 4.5 River Ribble Catchment 4.6 River Wyre 4.7 River Derwent 5. -

Bishopgate Gardens a New Way of Living in the Heart of Preston Welcome to the Heaton Group

Bishopgate Gardens A new way of living in the heart of Preston Welcome to The Heaton Group Founded in Manchester, The Heaton Group creates unique property investment opportuniti es for serious property investors. Starti ng out four generati ons ago procuring property, land and development projects, The Heaton Group has over 50 years of experience, off ering a personal approach to the property investment lifecycle by focusing on quality, effi ciency and rental yield. We pride ourselves in developing high quality opportuniti es in half of the ti me of the average UK property developer. This is only possible thanks to our development team, our dedicated in house planning team and our strong partnerships within the local community which gives us the capacity to bring to market up to 18 projects every 8 weeks. Last year alone, The Heaton Group developed and delivered over 230 build-to-rent properti es in and around the Greater Manchester area. We are proud to be a big part of the evoluti on of Preston going forward. As a major part of the Northern regenerati on scheme, Preston is being viewed as a beacon to other developing areas in the UK of how to regenerate correctly; providing a bett er lifestyle to residents both new and existi ng. “ We know affordable properties in key commuter locations across the North West are in demand; that’s why we carefully select buildings in city centres close to transport links and fi nish them to an exceptional standard, ensuring appeal to both the rental and owner occupier markets.” John Heaton, 2019 2 THE HEATON GROUP | BISHOPGATE GARDENS, PRESTON THE HEATON GROUP | BISHOPGATE GARDENS, PRESTON 3 Introduction: Preston: Investment into Preston What you need to know Recommendati ons made as early Preston is on the up, supported by a bold Masterplan from the council as 2011 resulted in Preston City and private investment. -

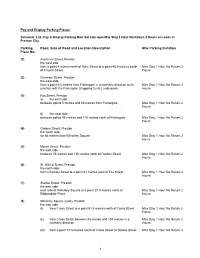

Schedule 1.02: Pay & Display Parking Mon-Sat 8Am-6Pm Max Stay 1 Hour

Pay and Display Parking Places Schedule 1.02: Pay & Display Parking Mon-Sat 8am-6pm Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Hours on roads in Preston City Parking Road, Side of Road and Location Description Max Parking Duration Place No. (1) Avenham Street, Preston the west side from a point 4 metres north of Syke Street to a point 46.5 metres south Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 of Church Street Hours (2) Charnley Street, Preston the west side from a point 6.5 metres from Fishergate in a northerly direction to its Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 junction with the Fishergate Shopping Centre underpass Hours (3) Fox Street, Preston a) the east side between points 5 metres and 26 metres from Fishergate Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Hours b) the west side between points 96 metres and 116 metres north of Fishergate Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Hours (4) Garden Street, Preston the south side for 46 metres from Winckley Square Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Hours (5) Mount Street, Preston the east side between 35 metres and 136 metres north of Garden Street Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Hours (6) St. Wilfrid Street, Preston the north side from Charnley Street to a point 31 metres west of Fox Street Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Hours (7) Starkie Street, Preston the east side east side of Winckley Square to a point 37.5 metres north of Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Ribblesdale Place Hours (8) Winckley Square (east), Preston the east side (i) from Cross Street to a point 51.5 metres north of Cross Street Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 Hours (ii) from Cross Street between 58 metres and 107 metres in a Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 northerly direction Hours (iii) from a point 10.5 metres south of Cross Street to Starkie Street Max Stay 1 Hour No Return 2 1 Parking Road, Side of Road and Location Description Max Parking Duration Place No. -

Mormon Baptismal Site in Chatburn, England

Carol Wilkinson: Baptismal Site in Chatburn, England 83 Mormon Baptismal Site in Chatburn, England Carol Wilkinson The location of a baptismal site in the village of Chatburn, England, used by Mormon missionaries in the 1830s and 1840s has been identified. This village, along with the neighboring community of Downham, was the location of a large number of Mormon conversions when the message of the restored gospel was first preached to the inhabitants during this time period. The first Mormon missionaries to England arrived in Liverpool in July 1837. These seven men (Heber C. Kimball, Orson Hyde, Willard Richards, Joseph Fielding, Isaac Russell, John Goodson, and John Snyder), quickly moved to Preston where they were successful in receiving converts and orga- nized a branch of the Church in that city. After organizing the Preston Branch they decided to separate and carry their message to other parts of the surround- ing country. Heber C. Kimball, Orson Hyde, and Joseph Fielding stayed in the Preston area and continued to proselytize and organize branches. Kimball and Fielding also began to venture into the upper reaches of the river Ribble Val- ley, teaching in Walkerford and Ribchester, where they experienced further success and organized additional branches of the Church.1 Further upstream from these villages lay the small communities of Chat- burn and Downham, just south of the river Ribble and north of towering Pen- dle Hill. Some of the most spiritual experiences of the missionary effort in the upper Ribble Valley occurred in these two villages. When Heber expressed a desire to visit the villages he noted receiving a negative response from some of his companions: “Having mentioned my determination of going to Chat- burn to several of my brethren, they endeavored to dissuade me from going, CAROL WILKINSON ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Exercise Sciences, Brigham Young University, and an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Church History and Doctrine, BYU. -

DISCOVER BOWLAND Contents Welcome

DISCOVER BOWLAND Contents Welcome The view from Whins Brow Welcome 3 Birds 18 Welcome to the Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Look out for the icons next Natural Beauty (AONB) and to a unique and captivating to our publications, means Discovery Map 4 Fishing 20 you can download it from our part of the countryside. Expanses of sky above dramatic website, and means you Landscape and Heritage 6 Flying 21 sweeps of open moorland, gentle and tidy lowlands, criss- can obtain it from one of the Tourist Information centres crossed with dry stone walls and dotted with picturesque Sustainable Tourism 8 Local Produce 22 listed on page 28 farms and villages - all waiting to be explored! Bus Services 10 Arts & Crafts 24 There is no better way of escaping from the hustle and bustle of everyday life and partaking in some the most peaceful and remote walking, riding and cycling in the Public Transport 11 Heritage 25 country. Explore some of the many unique villages steeped in history. While away your time observing some of the rare and enigmatic birds and wildlife, or simply Walking 12 Festival Bowland 26 indulge in sampling some of the very best local produce the area has to offer. Cycling 14 Accommodation 28 To make the most of your visit, why not stay a while? Bowland has a wide range of quality accommodation to suit all tastes. Horse Riding 16 Accommodation Listings 30 Access for All 17 Make Bowland your discovery! 2 www.fwww.forestofbowland.comorestofbowland.com 3 1 Discovery Map Situated in North West England, covering 803 square kilometres (300 sq miles) of rural Lancashire and North Yorkshire, the Forest of Bowland AONB is in two parts. -

Derby House, Preston

For sale On behalf of Joint Administrators Derby House 12 Winckley Square Preston PR1 3JJ January 2018 08449 02 03 04 gva.co.uk/13825 12 Winckley Square, Preston Summary ─ 1,378.76 sq m (14,841 sq ft) (IPMS) ─ Modern good quality City Centre office accommodation ─ Current passing rent £76,752 pa, rising to £97,374 pa by May 2019 ─ ERV circa £125,000 pa ─ Valuable parking provision / lobby and lift access ─ Potential for long term residential redevelopment ─ Offers invited for the Freehold interest 12 Winckley Square, Preston Location Description The property is prominently located on the The property comprises a detached four desirable Winckley Square within the heart storey office block extending to circa 15,000 of Preston City Centre. Centered around sq ft (net). Internally the accommodation attractive open gardens, the square is has recently been refurbished and dominated by Georgian architecture which comprises a central lobby area with was once an exclusive residential area. In stairwell / lift access running to each level of more recent times the area has become a the building. There are two suites on each prominent office location, housing many floor with the exception of the lower ground regional and national professional / financial floor, with the remainder of the occupiers. The square has received accommodation comprising ancillary significant funding in recent years to space. improve and regenerate the area. It is The property is currently 80% occupied, positioned within yards of Preston’s main comprising 5 tenants, being a mix of retail offering, with all local amenities within national and local occupiers.