Herding Behavior in the Pakistan Stock Exchange: Some New Insights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stock Market in Pakistan: an Overview

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Stock Market in Pakistan: An Overview Iqbal, Javed Monash University July 2008 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/11868/ MPRA Paper No. 11868, posted 04 Dec 2008 06:14 UTC Stock Market in Pakistan: An Overview Stock Market in Pakistan: An Overview By Javed Iqbal Department of Econometrics and Business Statistics, Monash University Australia and Department of Statistics, University of Karachi, Pakistan Postal Address: Department of Statistics, Karachi University, Karachi 75270, Pakistan Email: [email protected] 1 Stock Market in Pakistan: An Overview Stock Market in Pakistan: An Overview ABSTRACT This paper reviews the main features of the Stock market in Pakistan focussing on post- liberalization period. The aspects of the market investigated include liberalization of the market, integration the market with the world markets, trading and settlement mechanism, and corporate governance issues. Finally salient features of the market are compared to a selected set of emerging and developed markets. Pakistan’s stock market is smaller in size but is significantly more active than the markets of this size. In recent years the market has provided very high returns to investors. In 2002 the market was declared as the best performing stock market globally. 2 Stock Market in Pakistan: An Overview Stock Market in Pakistan: An Overview 1. NTRODUCTION The Karachi Stock Excahnge (KSE) is Pakistan’s first and one of the oldest stock exchanges in emerging markets. KSE was established in 18 September 1947 just two months after Pakistan became an independent state. The other exchanges in Pakistan, the Lahore Stock Exchange (LSE) and the Islamabad Stock Exchange (ISE), were estbalished in 1974 and 1997 respectively. -

Analyzing the Stock Markets Role As a Source of Capital Formation in Pakistan

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kanasro, Hakim Ali; Junejo, Mumtaz Ali; Junejo, Mansoor Ahmed Article Analyzing the stock markets role as a source of capital formation in Pakistan Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences (PJCSS) Provided in Cooperation with: Johar Education Society, Pakistan (JESPK) Suggested Citation: Kanasro, Hakim Ali; Junejo, Mumtaz Ali; Junejo, Mansoor Ahmed (2011) : Analyzing the stock markets role as a source of capital formation in Pakistan, Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences (PJCSS), ISSN 2309-8619, Johar Education Society, Pakistan (JESPK), Lahore, Vol. 5, Iss. 2, pp. 273-282 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/188030 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

The Effect of Uncertainty on Stock Returns and Risk-Returns (Volatility) Relationship Across Military and Democratic Regimes in Pakistan

Marketing and Branding Research 7(2020) 24-46 Marketing and Branding Research WWW.CIKD.CA The Effect of Uncertainty on Stock Returns and Risk-returns (Volatility) Relationship Across Military and Democratic Regimes in Pakistan Zareen Zafar1*, Danish Ahmed Siddiqui2 1, 2Karachi University Business School, University of Karachi, Pakistan ABSTRACT Keywords: This research includes empirical results in making a consistent understanding of investor Pakistan Stock Market, Stock sagacity, investment returns, and behavioral stock market performance in the behavioral Returns, Risk Returns, finance trend theoretical context. The data were collected using a long range of Returns data Military Regieme, Pakistan's stock market Since June 1994 to December 2018 on the two economic segments Democratic Regieme, known as the Military Period (1999-2008 and 2009-2018). Quantile Regression (QR) and Ordinary Least Square, Ordinary Least Square (OLS) carried out on future returns and risk-returns (volatility) where Quantile Regression, the independent variables Consumer Price Index (CPI), Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Uncertainty index Money Market Rate (MMR), Discount Rate (DR) and Pakistan's Uncertainty Index were taken at annual data base. The findings indicated that DR and past returns significantly impact future Received returns. Other factors such as GDP, inflations, MMR and conditions of instability, however, 14 October 2020 had no major impact on returns. With regard to the military process, all variables such as past Received in revised form returns, GDP, discount and cash market levels, as well as volatility, had a major return impact. 26 October 2020 Whereas in the process of democracy, no macroeconomic factor affected those returns. With regard to volatility, CPI appeared to be the only factor that positively impacted the volatility Accepted of share prices, as well as each of the two phases while all other factors had no significant 26 October 2020 effect overall. -

Shareholders Without CNIC.PDF

Gharibwal Cement Limited DETAIL OF WITHOUT CNIC SHAREHOLDERS S.No. Folio Name Address Current Net Dividend shareholding (Net of Zakat and Balance tax) 1 1 HAJI AMIR UMAR C/O.HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR COTTON MERCHANT,3RD FLOOR COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG, MCLEOD ROAD, P.O.BOX.NO.4124 586 KARACHI 578 2 3 MR.MAHBOOB AHMAD MOTI MANSION, MCLEOD ROAD, LAHORE. 11 11 3 11 MRS.FAUZIA MUGHIS 25-TIPU SULTAN ROAD MULTAN CANTT 1,287 1,271 4 19 MALIK MOHAMMAD TARIQ C/O.MALIK KHUDA BUX SECRETARY AGRICULTURE (WEST PAKISTAN), LAHORE. 110 108 5 20 MR. NABI AHMED CHAUDHRI, C/O, MODERN MOTORS LTD, VOLKSWAGEN HOUSE, P.O.BOX NO.8505, BEAUMONT ROAD, KARACHI.4. 2,193 2,166 6 24 BEGUM INAYAT NASIR AHMED 134 C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 67 66 7 26 MRS. AMTUR RAUF AHMED, 14/11 STREET 20, KHAYABAN-E-TAUHEED, PHASE V,DEFENCE, KARACHI. 474 468 8 27 MRS.AMTUL QAYYUM AHMED 134-C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 26 25 9 31 MR.ANEES AHMED C/O.DR.GHULAM RASUL CHEEMA BHAWANA BAZAR, FAISALABAD 649 642 10 36 MST.RAFIA KHANUM C/O.MIAN MAQSOOD A.SHEIKH M/S.MAQBOOL CO.LTD ILAMA IQBAL ROAD, LAHORE. 1,789 1,767 11 37 MST.ABIDA BEGUM C/O HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR 3RD FLOOR. COTTON EXCHANGE BUILDING, 1.1.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD, KARACHI. 2,572 2,540 12 39 MST.SAKINA BEGUM F-105 BLOCK-F ALLAMA RASHID TURABI ROAD NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2,657 2,625 13 42 MST.RAZIA BEGUM C/O M/S SADIQ SIDDIQUE CO., 32-COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG., I.I.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI. -

Analyzing the Stock Markets Role As a Source of Capital Formation in Pakistan

Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2011 Vol. 5 (2), 273-282 Analyzing the Stock Markets Role as a Source of Capital Formation in Pakistan Hakim Ali Kanasro (Corresponding Author) Associate Professor, Institute of Commerce, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Mumtaz Ali Junejo Professor, Department of Commerce, Shah AbdulLatif University, Khairpur, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Mansoor Ahmed Junejo Lecturer, Sukkur Institute of Business Administration, Sukkur, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper is to examine the stock markets role in the capital formation in Pakistan from the period 1st January 2001 to 31st December 2008. This analytical study is based on the data collected from the secondary sources such as State Bank of Pakistan and three stock exchanges; Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad Stock exchanges. The stock market size of capital, number of listed companies and liquidity positions has been examined in the study. The study reveals that Karachi Stock exchange is the oldest and biggest Stock exchange of Pakistan and it is the first mover to adapt institutional developments, new policies and procedures in the business of securities exchange and shares a big role in the capital formation in Pakistan. In recent years all stock exchanges have implemented the advanced technology and fully automated trading systems. This has changed the stock markets role in the capital formation as great boom has been observed during the study period. Keywords: Stock Exchange, Investment, Capitalization, Economic growth, Financial Institutions. 1. Introduction Stock markets are crucial in mobilizing domestic and foreign capital resources and channeling that capital efficiently to the most productive usage for a country. -

FINANCIAL MARKET DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY Launch

FINANCIAL MARKET DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY Launch of an SME Board by the Pakistan Stock Exchange 11 February 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development by Financial Market Development (FMD) Activity, Pakistan LAUNCH OF AN SME BOARD BY THE PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE (PSX) – FEBRUARY 11, 2017 REPORT COVERING 2 DEC 2016 – 11 FEB 2017 USAID FINANCIAL MARKET DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY, PAKISTAN 11 FEBRUARY 2017 PREPARED BY: CHRISTIAN C. JOHNSON, CONSULTANT CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................... 4 2. BACKGROUND & OVERVIEW ............................................ 5 3. TOR DELIVERABLES - DECEMBER 31, 2016 .................... 10 4. TOR DELIVERABLES - FEBRUARY 11, 2017 ..................... 10 5. SHORT LIST OF SME LAUNCH CANDIDATES .............. 13 6. SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS & NEXT STEPS ........ 16 APPENDIX 1 – FMD REPORT ON PSX SME BOARD – 2017- 2020 BUSINESS PLAN ......................................................... 20 APPENDIX 2 – STAKEHOLDER MEETINGS & FEEDBACK SESSIONS ............................................................................. 21 3 USAID’s Financial Market Development Activity, Pakistan 11 February 2017 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FMD was engaged by SECP/PSX to provide its technical/expert recommendations to accelerate the establishment of an SME Platform at PSX. Specific assistance to increase the pace and number of SME listings was a primary need. Based on FMD’s market assessment, and the study of developments related to the launch of SME Market in Pakistan, the following recommendations are being hereby provided: Rebrand the SME Platform: In line with the global trend of global stock exchanges to brand their second-tier markets with distinct names, FMD recommends that PSX should also rebrand its proposed SME Board to focus on growth enterprises vs. SME enterprises. For example, the SME Board could be rebranded as “GEM” (which would (referring to “Growth Enterprise Market”). -

Pakistan Stock Exchange Merger: a Prudent Move Or an Imprudent Impulse

International Journal of Education and Human Developments Vol. 3 No. 3; May 2017 Pakistan Stock Exchange Merger: A Prudent Move or an Imprudent Impulse Fazeelat Masood Bahria University, Karachi Campus Pakistan Abstract For more than two decades, demutualization has been forcing the way for the concept of stock exchange merger in the global financial markets. In Pakistan, demutualization fostered one-of- its-kind merger that took place with the amalgamation of three domestic exchanges into PSX. It allowed Pakistani exchanges to transfer from member owned to investor owned organizations. With an exploratory approach, the research has assessed PSX merger and its consequences on stock market of Pakistan. To a certain extent, PSX merger has led to effects identical to global mergers; however, its long term consequences are yet to be witnessed. Analysis showed that PSX merger is apparently a good move for Pakistani market as it has promised significant investments that are essential to upgrade and mobilize the market while keeping exchanges’ activities under direct surveillance. With key motives to attract private investments to upgrade the exchanges’ infrastructure and to mobilize exchange trading activities, PSX is found to have pros and cons that may substantiate in the long run. It is plausible to state that like every decision, PSX move has its foreseeable positive and negative effects that can be well apprehended with a wise approach to managing the demutualization process and it’s after effects. To state the fact, PSX decision is turning out to be a sagacious effort until now and if the authorities keep a hawk eye on both sides of the decree then this coin may turn over a new leaf in the history of Pakistani stock exchange. -

06-Capital Markets

CHAPTER 06 Capital Markets Capital markets are a broad category of markets banks and institutions in Europe and Asia held facilitating the buying and selling of financial trillions of dollars of these securities. instruments. In particular, there are two categories of financial instruments in which markets are The capital market structure in Pakistan consists involved. These are equity securities, which are of an apex regulator of the markets, the Securities often known as stocks, and debt securities, which and Exchange Commission Pakistan (SECP), are often known as bonds. Capital markets involve Pakistan Stock Exchange (emerged as a result of the issuing of stocks and bonds for medium-term merging three stock exchanges during current and long-term durations, generally terms of one year), Mercantile Exchanges, Central Depository year or more. Company (CDC) and a Clearing and Settlement Company. The structure further includes Other than the distinction between equity and intermediaries or market participants such as debt, capital markets are also generally divided brokers which handle the transaction of shares in into two categories of markets, the first of which the capital markets on behalf of investors. being primary markets. In primary markets, stocks and bonds are issued directly from companies to Capital markets in Pakistan play a crucial role in investors, businesses and other institutions, often mobilizing domestic resources and channeling through underwriting. Primary markets allow them efficiently to productive uses, thus raising companies to raise capital without or before national productivity. The level of capital market holding an initial public offering so as to make as development is an important determinant of level much direct profit as possible. -

List of Distribution Offices

LIST OF DISTRIBUTION OFFICES AKD Investment Management Limited Head Office 2nd Floor, Continental Trade Center Block-8, Clifton Karachi, Pakistan 92-21-111-AKDIML (111-253-465) 92-21-5373217 The following locations will be distribution points for the fund: AKD Securities (Private) Limited • Karachi Office -- Head Office Suite # 214, 2nd Floor Continental Trade Centre Block 8, Clifton Karachi - Pakistan UAN: 111-253-253 Fax: (92-21) 583-6517 • Islamabad Office M-4, Islamabad Stock Exchange Building, 101-E, Fazal-e-Haq Road, Blue Area, Islamabad - Pakistan UAN: 111-253-253 Fax: (92-51) 227-6621 • Lahore Office 512, 513, 5th Floor, Lahore Stock Exchange Building, 19, Khayaban-e- Aiwan-e-Iqbal Road, Lahore - Pakistan UAN: 111-253-253 Branch UAN: 111-253-111 Fax: (92-42) 628-0745 First International Investment Bank (Inter Bank) • Karachi Office 7th Floor, Shaheen Commercial Complex, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi-74200. E-mail: [email protected] • Lahore Office Ground Floor, 5 F.C.C, Syed Maratib Ali Road, Gulberg, Lahore. E-mail: [email protected] • Islamabad Office Mezzanine Floor, Razia Sharif Plaza, 90 - Blue Area, G-7, Islamabad. E-mail: [email protected] UNIVERSAL ACCESS NUMBERS Telephone: 111-234-234 Fax: 111-567-567 Bank of Punjab • Lahore Office Main Branch Lahore Telephone: 042-9200419, 9200383 Fax #: 042-9200351 Model Town Lahore Telephone: 042-9230254, 9230451 Fax #: 042-9230927 LCCHS Lahore Telephone 042-5741792, 5722885 Fax #: 042-5724365 • Sialkot Office Railway Road Sialkot Telephone: 052-9250097, 9250098 Fax #: 052-9250096 • Multan Office Quaid-e-Azam Road Multan Cantt. -

A Case Study of Karachi Stock Exchange

NUML International Journal of Business & Management ISSN 2410-5392 (Print), ISSN 2521-473X (Online) Vol. 12, No: 2. December, 2017 Relationship between Stock Prices and Macroeconomic Variables: A Case Study of Karachi Stock Exchange Zahid Mehmood Akhtar Muhammad Sohail Muhammad Haroon1, 2, 3 Abstract This study investigates the relationship between the stock prices and macroeconomic variables in Pakistan. The study uses monthly data from January 2001 to May 2012. This study used those variables which have not been previously evaluated. This study incorporated the effect of market crash 2008 and its implications for Karachi Stock Exchange. This study used Johansen Co-integration test, Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) to capture the association among the variables. The study found the long-run relationship between macroeconomics variables and stock prices. Impulse response and variance decomposition analysis have also been carried out for further verification of the result. Exports, Exchange Rate and Money Supply showed a positive and substantial relationship with stock prices while inflation and discount rate negatively affect stock prices. Index of industrial production had a positive but insignificant relationship with stock prices. Market crash had a negative relationship with stock prices and prolonged crises affected the stock prices significantly. The error correction term from VECM is significant and indicated short term adjustments towards the equilibrium path. Impulse response and variance decomposition exhibits pattern in conformance with the already obtained results. Keywords: Exchange Rate, Money Supply, Stock Exchange, Inflation Introduction The financial system of a country is comprised of the banking sector, financial institutions like insurance companies, pension funds, bond markets and stock exchange markets. -

To Download UBL Branch List

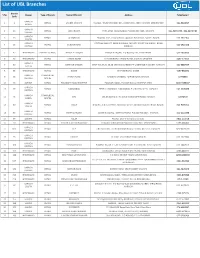

List of UBL Branches Branch S No Region Type of Branch Name Of Branch Address Telephone # Code KARACHI 1 2 RETAIL LANDHI KARACHI H-G/9-D, TRUST CERAMIC IND., LANDHI IND. AREA KARACHI (EPZ) EXPORT 021-5018697 NORTH KARACHI 2 19 RETAIL JODIA BAZAR PARA LANE, JODIA BAZAR, P.O.BOX NO.4627, KARACHI. 021-32434679 , 021-32439484 CENTRAL KARACHI 3 23 RETAIL AL-HAROON Shop No. 39/1, Ground Floor, Opposite BVS School, Sadder, Karachi 021-2727106 SOUTH KARACHI CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, OPP CITY COURT,MA JINNAH ROAD 4 25 RETAIL BUNDER ROAD 021-2623128 CENTRAL KARACHI. 5 47 HYDERABAD AMEEN - ISLAMIC PRINCE ALLY ROAD PRINCE ALI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.131, HYDERABAD. 022-2633606 6 46 HYDERABAD RETAIL TANDO ADAM STATION ROAD TANDO ADAM, DISTRICT SANGHAR. 0235-574313 KARACHI 7 52 RETAIL DEFENCE GARDEN SHOP NO.29,30, 35,36 DEFENCE GARDEN PH-1 DEFENCE H.SOCIETY KARACHI 021-5888434 SOUTH 8 55 HYDERABAD RETAIL BADIN STATION ROAD, BADIN. 0297-861871 KARACHI COMMERCIAL 9 65 NAPIER ROAD KASSIM CHAMBERS, NAPIER ROAD,KARACHI. 32775993 CENTRAL CENTRE 10 66 SUKKUR RETAIL FOUJDARY ROAD KHAIRPUR FOAJDARI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.14, KHAIRPUR MIRS. 0243-9280047 KARACHI 11 69 RETAIL NAZIMABAD FIRST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD, P.O.BOX NO.2135, KARACHI. 021-6608288 CENTRAL KARACHI COMMERCIAL 12 71 SITE UBL BUILDING S.I.T.E.AREA MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI 32570719 NORTH CENTRE KARACHI 13 80 RETAIL VAULT Shop No. 2, Ground Floor, Nonwhite Center Abdullah Harpoon Road, Karachi. 021-9205312 SOUTH KARACHI 14 85 RETAIL MARRIOT ROAD GILANI BUILDING, MARRIOT ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.5037, KARACHI. -

The Case of Pakistan Stock Exchange

International Journal of Experiential Learning & Case Studies 3 : 1 ( June 2018) pp. 01-08 From Mutualized Exchange to Investor-Owned Demutualized Entity: The Case of Pakistan Stock Exchange Saqib Sharif * Abstract This study provides an overview of the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) journey from not-for-profit mutually owned company to the for-profit demutualized entity. The wave of demutualization and public listing of stock markets around the globe is being witnessed for the last three decades. This study focuses on three main areas. First, in 2012, the stock market stood corporatized and demutual- ized as a public company limited by shares. Prior to 2012, the PSX (formerly called Karachi stock exchange) was a broker-owned company. The three nation- al stock exchanges of Pakistan merged together to form PSX in January 2016. Moreover, the 40% strategic ownership of PSX is transferred to the Chinese investors. The Pakistan stock market is listed on its own exchange from June 29, 2017 (self-listing) following the IPO process. Second, this study discusses the reasons for demutualization, such as investment in technology and global compe- tition; and regulatory implications of for-profit demutualized exchange. Lastly, selected market efficiency indicators are compared before and after integration to assess the benefit of demutualization. On a positive note, so far, the market wit- nessed higher liquidity, less excessive volatility, and better returns for investors in the post-merger period compared to pre-merger period. Keywords: Pakistan Stock Exchange, Demutualization, Self-listing, Market efficiency, Regulation INTRODUCTION On June 30, 2017, a get-together was arranged by the management of Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) in the trading hall of PSX at Karachi.