Pluralism with Syncretism: a Perspective from Latin American Religious Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enrique Iglesias' “Duele El Corazon” Reaches Over 1 Billion Cumulative Streams and Over 2 Million Downloads Sold Worldwide

ENRIQUE IGLESIAS’ “DUELE EL CORAZON” REACHES OVER 1 BILLION CUMULATIVE STREAMS AND OVER 2 MILLION DOWNLOADS SOLD WORLDWIDE RECEIVES AMERICAN MUSIC AWARD FOR BEST LATIN ARTIST (New York, New York) – This past Sunday, global superstar Enrique Iglesias wins the American Music Award for Favorite Latin Artist – the eighth in his career and the most by any artist in this category. The award comes on the heels of a whirlwind year for Enrique. His latest single, “DUELE EL CORAZON” has shattered records across the globe. The track (click here to listen) spent 14 weeks at #1 on the Hot Latin Songs chart, held the #1 spot on the Latin Pop Songs chart for 10 weeks and has over 1 billion cumulative streams and over 2 million tracks sold worldwide. The track also marks Enrique’s 14th #1 on the Dance Club Play chart, the most by any male artist. He also holds the record for the most #1 debuts on Billboard’s Latin Airplay chart. In addition to his recent AMA win, Enrique also took home 5 awards at this year’s Latin American Music Awards for Artist of the Year, Favorite Male Pop/Rock Artist and Favorite Song of the Year, Favorite Song Pop/Rock and Favorite Collaboration for “DUELE EL CORAZON” ft. Wisin. Earlier this month, Enrique went to France to receive the NRJ Award of Honor. For the past two years, Enrique has been touring the world on his SEX AND LOVE Tour which will culminate in Prague, Czech Republic on December 18th. Remaining 2016 Tour Dates Nov. -

Spanish NACH INTERPRET

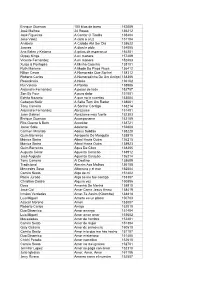

Enrique Guzman 100 kilos de barro 152009 José Malhoa 24 Rosas 136212 José Figueiras A Cantar O Tirolês 138404 Jose Velez A cara o cruz 151104 Anabela A Cidade Até Ser Dia 138622 Juanes A dios le pido 154005 Ana Belen y Ketama A gritos de esperanza 154201 Gypsy Kings A mi manera 157409 Vicente Fernandez A mi manera 152403 Xutos & Pontapés A Minha Casinha 138101 Ruth Marlene A Moda Do Pisca Pisca 136412 Nilton Cesar A Namorada Que Sonhei 138312 Roberto Carlos A Namoradinha De Um Amigo M138306 Resistência A Noite 136102 Rui Veloso A Paixão 138906 Alejandro Fernandez A pesar de todo 152707 Son By Four A puro dolor 151001 Ednita Nazario A que no le cuentas 153004 Cabeças NoAr A Seita Tem Um Radar 138601 Tony Carreira A Sonhar Contigo 138214 Alejandro Fernandez Abrazame 151401 Juan Gabriel Abrazame muy fuerte 152303 Enrique Guzman Acompaname 152109 Rita Guerra & Beto Acreditar 138721 Javier Solis Adelante 152808 Carmen Miranda Adeus Solidão 138220 Quim Barreiros Aeroporto De Mosquito 138510 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 136215 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 138923 Quim Barreiros Água De Côco 138205 Augusto César Aguenta Coração 138912 José Augusto Aguenta Coração 136214 Tony Carreira Ai Destino 138609 Tradicional Alecrim Aos Molhos 136108 Mercedes Sosa Alfonsina y el mar 152504 Camilo Sesto Algo de mi 151402 Rocio Jurado Algo se me fue contigo 153307 Christian Castro Alguna vez 150806 Doce Amanhã De Manhã 138910 José Cid Amar Como Jesus Amou 138419 Irmãos Verdades Amar-Te Assim (Kizomba) 138818 Luis Miguel Amarte es un placer 150703 Azucar -

Jewish Teenagers' Syncretism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2010 Jewish Teenagers’ Syncretism Philip Schwadel University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Sociology Commons Schwadel, Philip, "Jewish Teenagers’ Syncretism" (2010). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 174. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Review of Religious Research (2010) 51(3): 324-332. Copyright 2010, Springer. Used by permission. Jewish Teenagers’ Syncretism Philip Schwadel, Department of Sociology, University of Nebraska- Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA; [email protected] With the rapid rise of Jewish interfaith marriage and the migration of Jews away from traditional Jewish neighborhoods, many Jewish teenagers in the U.S. have little interaction with other Jews and little exposure to the Jewish religion. Here I use National Study of Youth and Religion survey data to examine Jewish teenagers’ syncretism or acceptance of different religious forms. The results show that Jewish teens are more syncretic than oth- er teens, and that variations in religious activity, an emphasis on personal religiosity, and living in an interfaith home explain some of the difference in syncretism between Jew- ish and non-Jewish teens. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Accord

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON TARIFFS AND TRADE MIN(86)/INF/3 ACCORD GENERAL SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ET LE COMMERCE 17 September 1986 ACUERDO GENERAL SOBRE ARANCELES ADUANEROS Y COMERCIO Limited Distribution CONTRACTING PARTIES PARTIES CONTRACTANTES PARTES CONTRATANTIS Session at Ministerial Session à l'échelon Periodo de sesiones a nivel Level ministériel ministerial 15-19 September 1986 15-19 septembre 1986 15-19 setiembre 1986 LIST OF REPRESENTATIVES LISTE DES REPRESENTANTS LISTA DE REPRESENTANTES Chairman: S.E. Sr. Enrique Iglesias Président; Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores Présidente; de la Republica Oriental del Uruguay ARGENTINA Représentantes Lie. Dante Caputo Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto » Dr. Juan V. Sourrouille Ministro de Economia Dr. Roberto Lavagna Secretario de Industria y Comercio Exterior Ing. Lucio Reca Secretario de Agricultura, Ganaderïa y Pesca Dr. Bernardo Grinspun Secretario de Planificaciôn Dr. Adolfo Canitrot Secretario de Coordinaciôn Econômica 86-1560 MIN(86)/INF/3 Page 2 ARGENTINA (cont) Représentantes (cont) S.E. Sr. Jorge Romero Embajador Subsecretario de Relaciones Internacionales Econômicas Lie. Guillermo Campbell Subsecretario de Intercambio Comercial Dr. Marcelo Kiguel Vicepresidente del Banco Central de la Republica Argentina S.E. Leopoldo Tettamanti Embaj ador Représentante Permanante ante la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas en Ginebra S.E. Carlos H. Perette Embajador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la Republica Oriental del Uruguay S.E. Ricardo Campero Embaj ador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la ALADI Sr. Pablo Quiroga Secretario Ejecutivo del Comité de Politicas de Exportaciones Dr. Jorge Cort Présidente de la Junta Nacional de Granos Sr. Emilio Ramôn Pardo Ministro Plenipotenciario Director de Relaciones Econômicas Multilatérales del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto Sr. -

Biblical Faith and Other Religions: an Evangelical Assessment

Scholars Crossing SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 2007 Review: Biblical Faith and Other Religions: An Evangelical Assessment Michael S. Jones Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Epistemology Commons, Esthetics Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Philosophy Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Michael S., "Review: Biblical Faith and Other Religions: An Evangelical Assessment" (2007). SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations. 170. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/170 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS 479 discussion of the "big questions," and publication of the second edition of this important work reminds us again of Hick's enonnous influence upon religious studies and philosophy of religion. One need not be persuaded by his pluralistic hypothesis to appreciate his impact in shaping the discussions over religious diversity. REVIEWED BY HAROLD N ULAND TRINITY EVANGELICAL DIVINITY SCHOOL Biblical Faith and Other Religions: An Evangelical Assessment. Edited by David W. Baker. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2004. 176 pages. $12.99. Biblical Faith and Other Religions is, as the subtitle states, an evangeli cal consideration of what is often called "the problem of religions pluralism." It is a multi author work, the contents of which are a result ofthe annual meet ing of the Evangelical Theological Society in Toronto in 2002. -

Evangelical Responses to the Question of Religious Pluralism By

Evangelical Responses to the Question of Religious Pluralism By Cecily May Worsfold A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2011 ABSTRACT The relatively recent rise of religious pluralism has significantly affected the evangelical movement, the roots of which are traceable to the sixteenth century Reformation. In particular, the theological implications of religious pluralism have led to debate concerning the nature of core beliefs of evangelicalism and how these should be interpreted in the contemporary world. While evangelicals continue to articulate a genuine undergirding desire to “honour the authority of Scripture”, differing frameworks and ideals have led to a certain level of fracturing between schools of evangelical thought. This research focuses on the work of three evangelical theologians – Harold Netland, John Sanders and Clark Pinnock – and their responses to the question of religious pluralism. In assessing the ideas put forward in their major work relevant to religious pluralism this thesis reveals something of the contestation and diversity within the evangelical tradition. The authors' respective theological opinions demonstrate that there is basic agreement on some doctrines. Others are being revisited, however, in the search for answers to the tension between two notions that evangelicals commonly affirm: the eternal destiny of the unevangelised; and the will of God that all humankind should obtain salvation. Evangelicals are deeply divided on this matter, and the problem of containing seemingly incompatible views within the confines of “evangelical belief” remains. This ongoing division highlights the difficulty of defining evangelicalism in purely theological terms. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO PUBLIC CATHOLICISM AND RELIGIOUS PLURALISM IN AMERICA: THE ADAPTATION OF A RELIGIOUS CULTURE TO THE CIRCUMSTANCE OF DIVERSITY, AND ITS IMPLICATIONS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Michael J. Agliardo, SJ Committee in charge: Professor Richard Madsen, Chair Professor John H. Evans Professor David Pellow Professor Joel Robbins Professor Gershon Shafir 2008 Copyright Michael J. Agliardo, SJ, 2008 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Michael Joseph Agliardo is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ......................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents......................................................................................................................iv List Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................................................................vi List of Graphs ......................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................. viii Vita.............................................................................................................................................x -

The Social Context of Religion and Spirituality in the United States

C HA P TER 2 THE SOciaL CONTEXT OF ReLIGION AND SpiRITUALITY IN THE UNITED STATes Christopher G. Ellison and Michael J. McFarland Since the dissemination of the classic theoretical religion and in which religious groups compete for treatises of Marx, Durkheim, and Weber, sociologists— members and other resources (Warner, 1993). and many other social scientists—have widely Although some scholars employed such concepts assumed that the forces of modernity would erode loosely, others drew more heavily on economic the social power of religion. In the prevailing secu- approaches, notably “rational choice” perspectives larization narrative, processes such as social differ- (Stark & Finke, 2001). entiation and rationalization would prompt a retreat In the 21st century, contrary to the expectations of religion from the public sphere, resulting in reli- of some variants of secularization theory, the gious privatism and eventual decline (Tschannen, United States is regarded as one of the most reli- 1991). Such ideas dominated the sociological land- gious societies in the industrial West. Although eco- scape for most of the 20th century, and seculariza- nomic development and national wealth are tion theory continues to have its defenders (e.g., inversely related to religiousness throughout much Chaves, 1994), especially among many European of the world, the United States remains a stubborn sociologists (e.g., Bruce, 2002). Beginning in the late outlier (Norris & Inglehart, 2004). In contrast to 1980s, however, notions of secularization came widespread popular and scholarly understandings under harsh scrutiny by a growing number of U.S. of the nation’s founding, it is now believed that sociologists who were increasingly skeptical about much of the United States was relatively irreligious the relevance of this perspective to the U.S. -

Choose the Method for Aggregating Religious Identities That Is Most Appropriate for Your Research Conrad Hackett University of Maryland, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2018 Choose the Method for Aggregating Religious Identities that Is Most Appropriate for Your Research Conrad Hackett University of Maryland, [email protected] Philip Schwadel University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Gregory A. Smith Pew Research Center Elizabeth Podrebarac Sciupac Pew Research Center Claire Gecewicz Pew Research Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hackett, Conrad; Schwadel, Philip; Smith, Gregory A.; Sciupac, Elizabeth Podrebarac; and Gecewicz, Claire, "Choose the Method for Aggregating Religious Identities that Is Most Appropriate for Your Research" (2018). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 661. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/661 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. digitalcommons.unl.edu Choose the Method for Aggregating Religious Identities that Is Most Appropriate for Your Research Conrad Hackett,1,2 Philip Schwadel,1,3 Gregory A. Smith,1 Elizabeth Podrebarac Sciupac,1 and Claire Gecewicz 1 1 Pew Research Center 2 University of Maryland 3 University of Nebraska–Lincoln Corresponding author — Conrad Hackett, Pew Research Center, 1615 L Street NW, Suite 800, Washington, DC 20036–5621, USA. -

Religion and Politics in Ancient Egypt

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES ISSN Print: 2156-1540, ISSN Online: 2151-1559, doi:10.5251/ajsms.2012.3.3.93.98 © 2012, ScienceHuβ, http://www.scihub.org/AJSMS Religion and politics in ancient Egypt Etim E. Okon Ph.D. Department of Religious and Cultural Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to examine the pervasive influence of religion on politics in a monarchical ancient African kingdom. After a critical reflection on the mythology and cultus of the Sun-God, the apotheosis of the Pharaoh and the cult of the dead in ancient Egyptian society, it was found that religion was indispensable in ancient Egypt. Religion and politics in ancient Egyptian society were inseparable. Ancient Egyptians were incurably religious. Social and political life was a religious phenomenon. The king of Egypt, Pharaoh was not only despotic, but comprehensively authoritarian. Ancient Egyptian society was a monarchy. The idea of democracy was unknown in ancient Egypt. Key words: Religion and Politics in Ancient Egypt; Egypt and the Sun-God; Egyptian Mythology; INTRODUCTION differences. It is also evident that even though the god – Ra, was known by seventy-five different Religion was the dominant social force in ancient names, very few of the hundreds of deities were Egypt. Religious influence was pervasive affecting worshiped nationally. The most influential pantheon almost everything. Egyptian religion developed from was made up of the trinity – Osiris, Isis (his wife), and simple polytheism to philosophic monotheism, with Horus (his son). Egyptians also worshiped the every community having a guardian deity which “cosmic” gods under the leadership of Ra, the sun- personified the powers of nature. -

Syncretism, Revitalization and Conversion

RELIGIOUS SYNTHESIS AND CHANGE IN THE NEW WORLD: SYNCRETISM, REVITALIZATION AND CONVERSION by Stephen L. Selka, Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Schmidt College of Arts and Humanities in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 1997 ABSTRACT Author: Stephen L. Selka. Jr. Title: Religious Synthesis and Change in the New World: Syncretism, Revitalization and Conversion Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Gerald Weiss, Ph.D. Degree: Master of Arts Year: 1997 Cases of syncretism from the New World and other areas, with a concentration on Latin America and the Caribbean, are reviewed in order to investigate the hypothesis that structural and symbolic homologies between interacting religions are preconditions for religious syncretism. In addition, definitions and models of, as well as frameworks for, syncretism are discussed in light of the ethnographic evidence. Syncretism is also discussed with respect to both revitalization movements and the recent rise of conversion to Protestantism in Latin America and the Caribbean. The discussion of syncretism and other kinds of religious change is related to va~ious theoretical perspectives, particularly those concerning the relationship of cosmologies to the existential conditions of social life and the connection between religion and world view, attitudes, and norms. 11 RELIGIOUS SYNTHESIS AND CHANGE lN THE NEW WORLD: SYNCRETISM. REVITALIZATION AND CONVERSION by Stephen L. Selka. Jr. This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor. Dr. Gerald Weiss. Department of Anthropology, and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee.