Dame Edna Définitif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mongrel Media Presents a Film by Adam Elliot

Mongrel Media Presents A Film by Adam Elliot (92 min., Australia, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Synopsis The opening night selection of the 2009 Sundance Film Festival and in competition at the 2009 Berlin Generation 14plus, MARY AND MAX is a clayography feature film from Academy Award® winning writer/director Adam Elliot and producer Melanie Coombs, featuring the voice talents of Toni Collette, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Barry Humphries and Eric Bana. Spanning 20 years and 2 continents, MARY AND MAX tells of a pen-pal relationship between two very different people: Mary Dinkle (Collette), a chubby, lonely 8-year-old living in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia; and Max Horovitz (Hoffman), a severely obese, 44-year-old Jewish man with Asperger’s Syndrome living in the chaos of New York City. As MARY AND MAX chronicles Mary’s trip from adolescence to adulthood, and Max’s passage from middle to old age, it explores a bond that survives much more than the average friendship’s ups-and-downs. Like Elliot and Coombs’ Oscar® winning animated short HARVIE KRUMPET, MARY AND MAX is both hilarious and poignant as it takes us on a journey that explores friendship, autism, taxidermy, psychiatry, alcoholism, where babies come from, obesity, kleptomania, sexual differences, trust, copulating dogs, religious differences, agoraphobia and many more of life’s surprises. -

Friends Newsletter

FRIENDS OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA INC. WINTER 2016 Meet the Volunteer MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR Dear Friends Thank you to the many Friends who responded with sustained support to the sad news that June 2016 sees the final print issue of the National Library of Australia Magazine. Your decision to remain Friends is both heartening and encouraging. We continue to support the Library as it maintains its essential contribution to the vitality of Australian culture and heritage under increasingly Roger, how long have you been a volunteer at the Library? tight fiscal constraints. I joined the Library as a volunteer 15 years ago, beginning I was recently in the Treasures Gallery and fell into when the blockbuster exhibition, Treasures from the World’s conversation with a gentleman who had travelled from Great Libraries, was launched. Canada just to see items in the collection. He was more Tell us about your career prior to joining the Library’s than excited to be there; although he uses Trove and other Volunteer Program. NLA digital records back in Nova Scotia, the opportunity Part of my early career was spent in Tanzania, with the Australian to see the tangible historical documents was inspiring for Volunteers Abroad scheme. I taught economics and also him. Australians cherish their trips to foreign museums and assisted with adult education. When I moved to Canberra in galleries, and this conversation reminded me that we have 1970, I soon joined the newly created Department of Aboriginal much of inestimable cultural and historical value right here Affairs. For much of the two decades that followed, I was a policy at the NLA. -

Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections

University of Wollongong Research Online Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections 11-1977 Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Robert Page Editor Lucy Wagner Editor Bruce Knappett Associate Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia Recommended Citation Page, Robert; Wagner, Lucy; and Knappett, Bruce, (1977), Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977, Theatre Publications Ltd., New Lambton Heights, 66p. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia/14 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Description Contents: Departments 2 Comments 4 Quotes and Queries 5 Letters 6 Whispers, Rumours and Facts 62 Guide, Theatre, Opera, Dance 3 Spotlight Peter Hemmings Features 7 Tracks and Ways - Robin Ramsay talks to Theatre Australia 16 The Edgleys: A Theatre Family Raymond Stanley 22 Sydney’s Theatre - the Theatre Royal Ross Thorne 14 The Role of the Critic - Frances Kelly and Robert Page Playscript 41 Jack by Jim O’Neill Studyguide 10 Louis Esson Jess Wilkins Regional Theatre 12 The Armidale Experience Ray Omodei and Diana Sharpe Opera 53 Sydney Comes Second best David Gyger 18 The Two Macbeths David Gyger Ballet 58 Two Conservative Managements William Shoubridge Theatre Reviews 25 Western Australia King Edward the Second Long Day’s Journey into Night Of Mice and Men 28 South Australia Annie Get Your Gun HMS Pinafore City Sugar 31 A.C.T. -

Collection Name

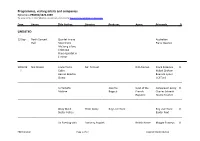

Programmes, visiting artists and companies Ephemera PR8492/1870-1899 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Title Author Director Producer Agent Principals D UNDATED 23 Sep Perth Concert Quartet in one Australian Hall Movement Piano Quartet My Song is love Unknown Piano Quartet in C minor 1890-95 Not Stated Uncle Tom's Mr. Trimnel N.D.Aikman Frank Bateman 0 ? Cabin. Mabel Graham Harriet Beecher Beatrice Lyster Stowe J.Clifford ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Le Tartuffe Jean De Govt of the Genevieve Leomy 0 Moliere Regault French Charles Schmitt Republic Giselle Tourtet ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Betty Blokk- Peter Batey Reg Livermore Reg Livermore 0 Buster Follies Baxter Funt ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ An Evening with Anthony Asquith British Home Margot Fonteyn 0 PR8492/UND Page 1 of 19 Copyright SLWA ©2011 Programmes, visiting artists and companies Ephemera PR8492/1870-1899 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Title Author Director Producer Agent Principals D the Royal Ballet Entertainment Rudolf Nureyev Ltd ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Fabian Lee Gordon Lee Gordon -

On STAGE WA MARITIME MUSEUM FREMANTLE 16.02.2019—09.06.2019 CONTENTS

LEARNING RESOURCE KIT WA MARITIME MUSEUM presents A TOURING EXHIBITION BY ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE AND THE AUSTRALIAN MUSIC VAULT on STAGE WA MARITIME MUSEUM FREMANTLE 16.02.2019—09.06.2019 CONTENTS: Welcome How to use this Resource Section 1 - What is an Exhibition? 1.1. Activity Introduction 1.2. Prezi – What is an Exhibition? 1.3. Types of Exhibition Spaces 1.4. The ACM Collection 1.5. Acquiring Artefacts and Artworks 1.6. Conservation of Artworks and Artefacts 1.7. ACM on Display 1.8. Activity – Who works in the team? 1.9. The Collections Team 1.10. Activity – The Exhibition of Me Section 2 – All Things Kylie 2.1. Introduction 2.2. Prezi – Kylie Career Overview 2.3. Video – Kylie – the curator’s insight 2.4. Activity – Visiting the Kylie on Stage Exhibition live or online Section 3 – Designing an Icon 3.1. What makes an Icon? 3.2. Interpreting a Song 3.3. Activity – Interpreting a Song 3.4. Garment Design Elements and Principles 3.5. Activity – Design Elements and Principles 3.6. Activity – Design Analysis Activity 3.7. Activity – Mood Board Activity 3.8. Activity – Designing a Costume 3.9. Activity – Making a Costume Appendix A – Offer of Donation Form Appendix B – Condition Report - Kylie Costume Appendix C – ACM Exhibitions Appendix D – Catalogue Worksheet Appendix E – Condition Report – Blank Appendix F – Elements and Principles Template Novice Appendix G – Elements and Principles Template Advanced Appendix H – Croquis Templates Curriculum Links Credits WELCOME Thank-you for downloading the Kylie on Stage Learning Resources. We hope you and your students enjoy learning about collections, exhibitions, music and costumes and of course Kylie Minogue as much as us! Kylie on Stage is a major free exhibition celebrating magical moments from Kylie’s highly successful concert tours around Australia. -

Barry Humphries

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID BARRY HUMPHRIES PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAMS AND EPHEMERA (PROMPT) PRINTED AUSTRALIANA JANUARY 2015 Barry Humphries was born in Melbourne on the 17th of February 1934. He is a multi-talented actor, satirist, artist and author. He began his stage career in 1952 in Call Me Madman. As actor he has invented many satiric Australian characters such as Sandy Stone, Lance Boyle, Debbie Thwaite, Neil Singleton and Barry (‘Bazza’) McKenzie - but his most famous creations are Dame Edna Everage who debuted in 1955 and Sir Leslie (‘Les’) Colin Patterson in 1974. Dame Edna, Sir Les and Bazza between them have made several sound recordings, written books and appeared in films and television and have been the subject of exhibitions. Since the 1960s Humphries’ career has alternated between England, Australia and the United States of America with his material becoming more international. Barry Humphries’ autobiography More Please (London; New York : Viking, 1992) won him the J.R. Ackerley Prize in 1993. He has won various awards for theatre, comedy and as a television personality. In 1994 he was accorded an honorary doctorate from Griffith University, Queensland and in 2003 received an Honorary Doctorate of Law from the University of Melbourne. He was awarded an Order of Australia in 1982; a Centenary Medal in 2001 for “service to Australian society through acting and writing”; and made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for "services to entertainment" in 2007 (Queen's Birthday Honours, UK List). Humphries was named 2012 Australian of the Year in the UK. The Barry Humphries PROMPT collection includes programs, ephemera and newspaper cuttings which document Barry Humphries and his alter egos on stage in Australia and overseas from the beginning of his career in the 1950s into the 21st Century. -

Uncovering the Essence of Humphries

UNCOVERINGTHE ESSENCE OF HUMPHRIES It's not certain if he found them under his bed, as priceless artefacts are supposed to be found, but Melbourne's Rabbi John Levi can claim the credit for uncovering a cache of the earliest known recordings by Barry Humphries, Australia's finest post war comic talent . Not that he will though . Unlike his more famous participant in the Melbourne Univer sity 'Dada' group of the early 1950s, the good rabbi keeps a low public profile these days, having forsaken the grim, satirical, anarchic and often cruel cavortings of his surreal soulmates for a life of service and no small amount of reflection. · For more than forty years, Levi thoughtfully preserved a number of one-off discs, which he recently handed over, at Humphries urging, to the specialist Melbourne independent Raven Records label for rehabilitation and eventual public issue as part of the Moonee Ponds Muse series of CDs. Among the highlights of this exhumed treasure trove is a short 'Memorial Paper' reading called Cinderella, at the end of which the young Humphries, three years or more before the 1955 debut performance of Edna Everage, rails angrily against the 'perversions' of men disguised as women. They should, he warned, 'be watched with care'. Harsh, affronting and almost seditious, even in the nineties, it is impossible to imagine the monologues, sketches, improvisations and discordant musical meanderings on the discs being accepted or even understood by anyone outside a close circle of co-conspirators in the early fifties. 'Nearly all our sketches of the period,' Barry recalls, 'describe people exchanging identities, going mad or degenerating into a kind of baleful infantilism.' Right: Barry Humphries as Edna Everage Centre: Edna Everage, 1955, Opposite page below: First known photograph of Edna Everage, 1957-58 All of which was part and parcel of customised Dadaism as Humphries conceived it. -

“Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens's

“Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens’s Novels Marc Napolitano A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by Advisor: Allan Life Reader: Laurie Langbauer Reader: Tom Reinert Reader: Beverly Taylor Reader: Tim Carter © 2009 Marc Napolitano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Marc Napolitano: “Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens’s Novels (Under the direction of Allan Life) This project presents an analysis of various musical adaptations of the works of Charles Dickens. Transforming novels into musicals usually entails significant complications due to the divergent narrative techniques employed by novelists and composers or librettists. In spite of these difficulties, Dickens’s novels have continually been utilized as sources for stage and film musicals. This dissertation initially explores the elements of the author’s novels which render his works more suitable sources for musicalization than the texts of virtually any other canonical novelist. Subsequently, the project examines some of the larger and more complex issues associated with the adaptation of Dickens’s works into musicals, specifically, the question of preserving the overt Englishness of one of the most conspicuously British authors in literary history while simultaneously incorporating him into a genre that is closely connected with the techniques, talents, and tendencies of the American stage. A comprehensive overview of Lionel Bart’s Oliver! (1960), the most influential Dickensian musical of all time, serves to introduce the predominant theoretical concerns regarding the modification of Dickens’s texts for the musical stage and screen. -

COMIC AUSTRALIAN AUTOBIOGRAPHY David Mccooey

MY LIFE AS A JOKE: COMIC AUSTRALIAN AUTOBIOGRAPHY David McCooey - Deakin Un iversity In the television guide earlier this year I found the following description of a film: 'An unhappily married couple try to kill each other. 1987 comedy'. Obviously content is no criterion for judging what is comic. Nevertheless, at first squint comic autobiography may seem oxymoronic. Life, unlike comedy, does not end in marriage (despite what some wits might say) but, like tragedy, it does end in death. Comedy may also seem antipathetic to autobiography, since it is peopled by knaves, fools, gulls, dupes, rogues, tricksters, cuckolds, dandies, transvestites, indistinguishable twins and the two-dimensional. All this, we think wistfully, is not life. This is why I'm interested in comic autobiography. Recent theories of autobiography have generally been anti-realist in stance. This stems from, in the main, a suspicion of narrative. Narrative and daily life, it is believed, are inimical. Adding the mode of comedy only seems to make it all the more suspect. Or, as a character in the comic autobiography of the Welsh writer Gwyn Thomas puts it, 'Anybody preoccupied with the thought of laughter is bound to end up as a corrupt sort of bastard' (129). This problem of anti-realism lurks behind many theories of comedy, such as that of Jonathan Miller (an ex-comedian) which proposes that comedy 'involves the rehearsal of alternative categories and classifications of the world' (1 1 ), that it is a 'sabbatical let out ...to put things up for grabs' (12). If this is so, it would seem that autobiography would be hard pressed to be thematically comic. -

Barry Humphries, Satirist of Suburbia • Tim Bowden Barry Humphries, Satirist of Suburbia • Tim Bowden

IN THIS ISSUE: • TIM BOWDEN ON BARRY HUMPHRIES • CATHERINE HORNE DISCUSSES THE LANGUAGE OF NEW IDEA • BERNADETTE HINCE EXAMINES THE CLARET ASH PUBLISHED TWICE A YEAR • APRIL 2017 • VOLUME 26 • NO. 1 EDITORIAL BARRY HUMPHRIES, In this edition, writer Tim Bowden SATIRIST OF SUBURBIA shares with us his reflections on Barry Humphries in an entertaining article TIM BOWDEN that reminds us of how important Growing up in Hobart in the 1950s at the height of Prime Minister Robert Menzies’ long Humphries has been in adding reign can be described as comfortable enough, but not very exciting. Despite Menzies’ expressions to the rich lexicon of exhortation that we were ‘British to the bootstraps’, we knew we weren’t. Australian English. Immediate relief was provided by the advent of a young Barry Humphries’ tilts at English. in Australian Hills hoist at the iconic looks blog Our latest Melbourne’s staid and stultifying suburbia (‘where the cream brick veneers stay hygienic We also have two contributions to for years’) which came to us in Taswegia in the form of two small, long-playing vinyl very different aspects of language in records, played at 33 ¹/³ rpm on our parents’ turntables. I still have them. Titled ‘Wild Australia. Bernadette Hince writes Life in Suburbia’, these prized discs introduced us to Edna Everage and the moribund @ozworders @ozworders about the claret ash, a common monotone of Sandy Stone. The back cover blurb, written by Robin Boyd (noted Australian architect and author of The Great Australian Ugliness), describes the audio feature of the Australian landscape, treasures awaiting: ANDC and Catherine Horne, a PhD candidate Barry Humphries is one of the funniest men you could find this side of hysteria. -

For Your Consideration

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION Dear Industry Colleague, For your consideration, Warner Bros. Pictures has arranged screenings in several cities for you and a guest. THE LOS ANGELES RealD Theater Harmony Gold Malibu Twin Cinema DARK KNIGHT 100 North Crescent Preview House 3822 Cross Creek Road RISES Beverly Hills 7655 Sunset Blvd. Malibu Los Angeles Directors Guild of America Rave 18 (IMAX) 7920 Sunset Blvd. IMAX 6081 Center Drive, LA Los Angeles 3003 Exposition Blvd. Santa Monica Warner Bros. Studio ARGO 4000 Warner Blvd., Burbank Gate #4 / Hollywood Way NEW YORK Directors Guild of America Tribeca Screening Room Warner Bros. 110 West 57th Street, New York 375 Greenwich St. Screening Room CLOUD (Between Franklin and Moore) 1325 Avenue of the Americas ATLAS Dolby 88 New York New York 1325 Avenue of the Americas New York THE SAN FRANCISCO Delancey Screening Room Premier Theatre (ILM) Variety Club HOBBIT: 600 The Embarcadero Letterman Digital Arts Center Preview Room AN UNEXPECTED San Francisco 1 Letterman Drive, #B 582 Market Street JOURNEY San Francisco San Francisco Dolby Screening Room 100 Potrero Avenue Saul Zaentz Media Center San Francisco 2600 10th Street Berkeley MAGIC LONDON MIKE Covent Garden Hotel Soho Hotel Soho Screening Rooms Lower Ground Floor 4 Richmond Mews (Mr. Young’s) 10 Monmouth Street (Off Dean St.) 14 D’Arblay Street London London London Screenings may be monitored for unauthorized recording. By attending, you agree not to bring any audio or video recording device into the theatre. Any attempted use of such devices will result in immediate removal from the theatre, forfeiture of the device and may subject you to criminal and civil liability. -

2007 - 2008 Annual R

Live Performance Australia Annual Report 2007 - 08 Contents President’s Report ······································································································································· Page 3 Chief Executive Report ································································································································ Page 4 Workplace Relations ···································································································································· Page 5 Award Modernisation, Proposed Changes to the Migration Regulations Workplace Relations ···································································································································· Page 6 Payment for Archival Recordings, OH&S Update, Priorities for 2009 Policy and Strategy ······································································································································ Page 8 Code of Practice for the Ticketing of Live Entertainment in Australia, Ticket Attendance and Revenue Survey, Emerging Producers’ Program, Industry Case Study Project, Australia 2020 Summit Policy and Strategy ······································································································································ Page 9 Contemporary Music Working Group, Arts Access, Child Employment Policy and Strategy ······································································································································