American University Thesis and Dissertation Template for PC 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

Comes to Life in ELLA, a Highly-Acclaimed Musical Starring Tina Fabrique Limited Engagement

February 23, 2011 Jazz’s “First Lady of Song” comes to life in ELLA, a highly-acclaimed musical starring Tina Fabrique Limited engagement – March 22 – 27, 2011 Show features two dozen of the famed songstresses’ greatest hits (Philadelphia, February 23, 2011) — Celebrate the “First Lady of Song” Ella Fitzgerald when ELLA, the highly-acclaimed musical about legendary singer Ella Fitzgerald, comes to Philadelphia for a limited engagement, March 22-27, 2011, at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. Featuring more than two-dozen hit songs, ELLA combines myth, memory and music into a stylish and sophisticated journey through the life of one of the greatest jazz singers of the 20th century. Broadway veteran Tina Fabrique, under the direction of Rob Ruggiero (Broadway: Looped starring Valerie Harper, upcoming High starring Kathleen Turner), captures the spirit and exuberance of the famed singer, performing such memorable tunes as “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” “That Old Black Magic,” “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” and “It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).” ELLA marks the first time the Annenberg Center has presented a musical as part of its theatre series. Said Annenberg Center Managing Director Michael J. Rose, “ELLA will speak to a wide variety of audiences including Fitzgerald loyalists, musical theatre enthusiasts and jazz novices. We are pleased to have the opportunity to present this truly unique production featuring the incredible vocals of Tina Fabrique to Philadelphia audiences.” Performances of ELLA take place on Tuesday, March 22 at 7:30 PM; Thursday, March 24 at 7:30 PM; Friday, March 25 at 8:00 PM; Saturday, March 26 at 2:00 PM & 8:00 PM; and Sunday, March 27 at 2:00 PM. -

One Night with Fanny Brice

The American Century Theater presents About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional presents nonprofit theater company dedicated to presenting great, important, and worthy American plays of the twentieth century—what Henry Luce called “the American Century.” A Robert M. McElwaine American Reflections Project production of The company’s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past playwrights, nor can we afford to surrender the moorings to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all Americans, of all ages, origins, and points of view. In particular, we strive to create theatrical experiences that entire families can watch, enjoy, and discuss long afterward. The Robert M. McElwaine American Reflections Project with Esther Covington as Fanny One Night with Fanny Brice Honorary Producers November 5–27, 2010 Andrew Scott McElwaine Ann Marie Plubell Rosslyn Spectrum Theatre Harry and Lucille Stanford 1611 North Kent Street, Arlington VA Anonymous Director Musical Director Producers Ellen Dempsey Tom Fuller Rip Claassen About the Robert M. McElwaine American Reflections Project Rhonda Hill “Reflections” is an American Century Theater initiative designed to inspire and produce new and original stage works that compliment the company’s Stage Manager Scenic Design Lighting Design repertoire of important American plays and musicals from the 20th century. Arthur Rodger Patrick Lord Steven L. -

The Speaker's

Sekou Andrews: The Speaker’s Bio Sekou Andrews is inspiring the business world one poem at a time with The Sekou Effect. As the world’s leading Poetic Voice, Sekou creates personalized poetic presentations that give voice to the messages and missions of organizations and help them tell their most powerful stories. He is the creator of this cutting-edge speaking category that combines strategic storytelling, inspirational speaking, spoken word poetry, and the power of theater and comedy to make events into experiences, and transform audiences of informed receivers into enrolled responders. Sekou does more than inspire us with his story; he inspires us with our story. An elementary schoolteacher turned actor, musician, national poetry slam champion, entrepreneur, and now award-winning Poetic Voice, any given day may now find Sekou presenting an original talk for international marketing executives, giving a keynote speech at a leadership conference, or performing pieces for Barack Obama in Oprah’s backyard and Hillary Clinton in Quincy Jones’ living room. His work has been featured on such diverse national media outlets as ABC World News, MSNBC, HBO, Good Morning America, Showtime, MTV and BET, and he has performed privately for such prominent individuals as Maya Angelou, Larry King, Norman Lear, Sean “P-Diddy” Combs, and Coretta Scott King and family. Companies and organizations that have experienced “The Sekou Effect” include Kraft, Nike, Time Warner, Global Green, Banana Republic, eBay, Microsoft, Google, LinkedIn, Express, Paypal, General Mills, TEDx, Wieden+Kennedy, NBA, NCAA, Chopra Center, Experient, Singularity University and the Million Dollar Roundtable to name but a few. -

"When Hollywood Went to WAR

P ROGRAM SOURCE INTERNATIONAL "When Hollywood Went to WAR When Hollywood Went to War is the real life story of nearly 90 celebrities who served in the United State Military during World War II. In our research, we collected hundreds of photographs, films and several interviews of men and women from the entertainment world. These 1940’s celebrities, young and some older, took time out in their successful careers to protect and preserve our freedom. This presentation will explain where they went to serve and what battlefields and/or naval battles they experienced. The most challenging facet of the project was finding photographs of these celebrities in uniform and in various theaters of the war. Most of the men served in the Army Air Corp. The Navy was the second most chosen service. As part of our research we found out what aircraft they were flying and if they were in the Navy, the ships they were on. Kirk Douglas was on a Sub-Chaser. Jimmy Stewart piloted the B-24 Liberator. Jonathan Winters was an Anti-aircraft gunner on the U.S.S. Wisconsin in the Battle of Okinawa. Henry Fonda served on a destroyer, the U.S.S. Satterlee. Mickey Rooney served in the Army under General Patton and earned a Bronze Star. Tyrone Power was a Marine Corp pilot flying missions at the Battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Audie Murphy, the most decorated American soldier. Art Carney and Charles Durning were both wounded during the D-Day landing at Normandy, you will see that landing. Bea Arthur was a U.S. -

Powerful Theatre

Steven Connell is an acclaimed actor and renowned playwright, with work hailed by critics as “Powerful Theatre”, “Hilarious”, and “Brilliant”, but considering he is a Hollywood Slam Champion, a Los Angeles Slam Champion, a two-time HBO Def Poet and a National Poetry Champion (twice), he is perhaps best known for his work as a poet. Featured on ABC World News, Good Morning America, HBO Def Poetry and others, he has created work for such prestigious organizations as Global Green, TEDMED, Xprize Foundation, NIKE, Sony/Universal, Pioneer Electronics, American Cancer Society, Farmers Insurance, GAP, Banana Republic and Amnesty International, to name a few. Private highlights include performing at Oprah Winfrey’s celebration of Maya Angelou, the Quincy Jones Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Marion Anderson Gala (honoring Maya Angelou/Norman Lear); as well as special events for Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, (special request: Quincy Jones), and President Obama, (special request: Oprah Winfrey). In addition to being a poet, he served as creative director for the national spoken word tour and documentary, The Underground Poets Railroad, and as the artistic director for the Los Angeles Poetry Festival (Celebrate the Word). After that he was hired as poet and creative director for Norman Lear’s Declare Yourself. His work with Declare Yourself, and his partnership with Norman Lear, not only registered over a million voters it brought focus to the political facet of his work. This resulted in partnerships with Rock the Vote, Vote or Die, the ACLU, and the Pen Foundation, to name a few and led to his being published in the acclaimed anthology “Why Freedom Matters”. -

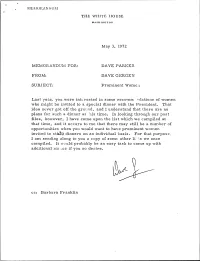

Dave Gergen to Dave Parker Re

MEf\IOR/\NIHJM THE WHITE HOUSE WASIIINGTON May 3, 1972 MEMORANDUM FOR: DAVE PARKER FROM: DAVE GERGEN SUBJECT: Prominent Wome~l Last year, you were int( rested in some recomrrj "c1ations of women who might be invited to a special dinner with the President. That idea never got off the ground, and I understand that there are no plans for such a dinner at :lis time. In looking through our past files, however, I have come upon the list which we compiled at that time, and it occurs to me that there Inay still be a number of opportunities when you would want to have prominent wom.en invited to st~~ dinners on an individual basis. For that purpose: I am sending along to you a copy of some other li i~S we once compiled. It would probably be an easy task to come up with additional nm, ~cs if you so desire. cc: Barbara Franklin r-------------------------------------------------------------- Acaflemic Hanna Arendt - Politic'al Scientist/Historian Ar iel Durant - Histor ian Gertrude Leighton - Due to pub lish a sem.ina 1 work on psychiatry and law, Bryn Mawr Katherine McBride - Retired Bryn Mawr President Business Buff Chandler - Business executive and arts patron Sylvia Porter - Syndicated financial colun1.nist Entertainment Mar ian And ",r son l Jacqueline I.. upre - British cellist Joan Gan? Cooney - President, Children1s Television Workshop; Ex(,cutive Producer of Sesaxne St., recently awarded honorary degre' fron'l Oberlin Agnes DeMille - Dance Ella Fitzgerald Margot Fonteyn - Ballerina Martha Graham. - Dance Melissa Hayden - Ballerina Helen Hayes Katherine Hepburn Jv1ahilia Jackson Mary Martin 11ary Tyler Moore Leontyne Price Martha Raye B(~verley Sills - Has appeared at "\V1-I G overnmcnt /Politics ,'. -

The American Pops Orchestra Family!

LOOKINGTO GET INVOLVED WITHTHE APO? The APO’s Don’t Rain On My Parade (Photo by Daniel Schwartz) Become Part of The American Pops Orchestra Family! Your donation will support: • 80+ musicians annually • Producing our mainstage concerts • APO’s monthly community concert series • Providing free and reduced tickets to veterans, seniors, students and others • Fulfi lling the APO’s Mission: to inspire new audiences to discover the wealth of material in the Great American Songbook in dynamic ways For more information about donating to the APO, please visit theamericanpops.org/donate Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater Fichandler Stage - May 19, 2018, 8:00 pm The American Pops Orchestra Presents Let's Misbehave: Cole Porter After Dark Starring Betty Who Featuring Liz Callaway Ali Ewoldt Luke Hawkins Bobby Smith Vishal Vaidya Luke S. Frazier, Music Director Directed by Kelly Crandall d'Amboise Media Sponsor: - 1 - SONG LIST Selections to include: Begin the Beguine Everytime We Say Goodbye Experiment Friendship From This Moment On I Happen to Like New York I’m a Gigolo Ignore Me/Why Can't You Behave In the Still of the Night It's De-Lovely Let’s Misbehave Love For Sale Night and Day So in Love/I Love You Somebody Loves You/You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To Too Darn Hot Why Shouldn’t I You Do Something to Me - 2 - WELCOME We’re all alone, no chaperone can get our number, the world’s in slumber... LET’S MISBEHAVE! Cole Porter’s lyrics aren’t the only things getting raucous this evening- we are thrilled you’ve joined us for an evening that’s sure to be delightful, delirious and delovely! Cole Porter’s music, made famous through the decades by such iconic vocalists as Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Dionne Warwick, Sheryl Crow, Natalie Cole and so many more, has inspired artists from every genre who have found the joy, beauty and fun in Porter's brilliant, timeless music. -

Florence ',Nightingale

-.. ~ .~. HEROINE , OUT OF ,,; FOCus: media images of . '. Florence ',Nightingale :::~r:-T II: RADIO, ~ lIl.V\JLvU\TIZA nONS BEATRICE J, KAUSCH and PHIUP A, KAUSCH ilm, radio, and television dramatizations of Florence myth. This process is the· result of both conscious FNightingale's life are particularly important in pro design on the part of actors, directors, and producers jecting a leading nurse's image to the public because and their unconscious integration and rep roduction of they dramatize her actions within he r social world and cultural paradigms. Through representations of Miss provide a role modeling effect that can be very useful in Nightingale, these productions have conveyed implicit acquiring support fo r the nursing profession. Such pro theories, beliefs, criticisms, and legitimations of the ductions do not "mirror" reality, but create an impres nursing profession's founder. Ideas about Nightingale sion of reality. like other forms of artistic and cultural arising in one generation are thus transformed and, in expression, they blend fact and fiction, history and turn, exert an influence on public perceptions within a changed historical setting. These forms of cultural ex pression provide resources of meaning about nursing Beatrice J. Kalisch. RN, EdD, FAAN, is Titus Professor of nursing and chairpe~n. parent·child nursing: Philip A. KlIlisch, PhD, is professor of that should be reinterpreted and adapted to new cir h;51ory, politics. lind economics of nursing. both at the University of cumstances. Michigan, Ann Arbor. This study was supPOrtlld by a research grllnt Florence Nightingale has inspired three feature fil m from the U.S. -

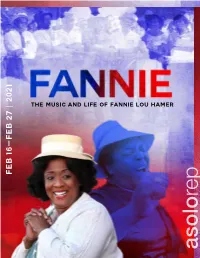

PDF Available Here

Feb 16—Feb 27 | 2021 the music and life of fannie lou hamer lou of fannie life and music the rep asolo Asolo Repertory Theatre presents in association with Goodman Theatre and Seattle Rep A Rolling World Premiere Production of CAST FANNIE: The Music and Life of E. FAYE BUTLER*..........................................................................Fannie Lou Hamer * Members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors Fannie Lou Hamer and Stage Managers in the United States. By CHERYL L. WEST MUSICIANS in alphabetical order Directed by HENRY DOMINIC GODINEZ FELTON OFFARD............................................................................Conductor/Guitar Music Direction and Arrangements by FELTON OFFARD AARON WASHINGTON............................................................................Percussion VIVIAN WELCH............................................................................................Keyboard Costume Design MICHAEL ALAN STEIN Lighting Design ETHAN VAIL Fannie will be performed without an intermission. Sound Design MATTHEW PARKER Projection Design AARON RHYNE Wig Design for Fannie MR. BERNARD Dramaturg CHRISTINE SUMPTION MUSICAL NUMBERS Song #1: I’m On My Way To Freedom (Instrumental) Scenic Consultant ADAM C. SPENCER Resident Hair & Make-up Design MICHELLE HART Song #2: Oh Freedom Production Stage Manager NIA SCIARRETTA* Song #3: I Love Everybody Song #4: This Little Light Of Mine Costume Coordinator DAVID COVACH Song #5: I Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round Assistant Stage Manager JACQUELINE SINGLETON* Projection Programmer KEVAN LONEY Song #6: We Shall Not Be Moved Script Coordinator JAMES MONAGHAN Song #7: I Love Everybody (Reprise) Song #8: Woke Up This Morning/Mind On Freedom Fannie is produced by special arrangement with Bruce Ostler/Kate Bussert, Song #9: Oh Lord You Know Just How I Feel BRET ADAMS, LTD., 448 West 44th Street, New York, NY 10036. -

Women Subjects on U.S. Postage Stamps

Women Subjects on United States Postage Stamps Queen Isabella of Spain appeared on seven stamps in the Columbian Exposition issue of 1893 — the first commemorative U.S. postage stamps. The first U.S. postage stamp to honor an American woman was the eight-cent Martha Washington stamp of 1902. The many stamps issued in honor of women since then are listed below. Martha Washington was the first American woman honored on a U.S. postage stamp. Subject Denomination Date Issued Columbian Exposition: Columbus Soliciting Aid from Queen Isabella 5¢ January 1893 Columbus Restored to Favor 8¢ January 1893 Columbus Presenting Natives 10¢ January 1893 Columbus Announcing His Discovery 15¢ January 1893 Queen Isabella Pledging Her Jewels $1 January 1893 Columbus Describing His Third Voyage $3 January 1893 Queen Isabella and Columbus $4 January 1893 Martha Washington 8¢ December 1902 Pocahontas 5¢ April 26, 1907 Martha Washington 4¢ January 15, 1923 “The Greatest Mother” 2¢ May 21, 1931 Mothers of America: Portrait of his Mother, by 3¢ May 2, 1934 James A. McNeil Whistler Susan B. Anthony 3¢ August 26, 1936 Virginia Dare 5¢ August 18, 1937 Martha Washington 1½¢ May 5, 1938 Louisa May Alcott 5¢ February 5, 1940 Frances E. Willard 5¢ March 28, 1940 Jane Addams 10¢ April 26, 1940 Progress of Women 3¢ July 19, 1948 Clara Barton 3¢ September 7, 1948 Gold Star Mothers 3¢ September 21, 1948 Juliette Gordon Low 3¢ October 29, 1948 Moina Michael 3¢ November 9, 1948 Betsy Ross 3¢ January 2, 1952 Service Women 3¢ September 11, 1952 Susan B. Anthony 50¢ August 25,