Harmonic Function in the Late Nineteenth-Century Chromatic Tonality of Wagner and Strauss: a Study of Extensions to Classical Prolongational Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riemann's Functional Framework for Extended Jazz Harmony James

Riemann’s Functional Framework for Extended Jazz Harmony James McGowan The I or tonic chord is the only chord which gives the feeling of complete rest or relaxation. Since the I chord acts as the point of rest there is generated in the other chords a feeling of tension or restlessness. The other chords therefore must 1 eventually return to the tonic chord if a feeling of relaxation is desired. Invoking several musical metaphors, Ricigliano’s comment could apply equally well to the tension and release of any tonal music, not only jazz. Indeed, such metaphors serve as essential points of departure for some extended treatises in music theory.2 Andrew Jaffe further associates “tonic,” “stability,” and “consonance,” when he states: “Two terms used to refer to the extremes of harmonic stability and instability within an individual chord or a chord progression are dissonance and consonance.”3 One should acknowledge, however, that to the non-jazz reader, reference to “tonic chord” implicitly means triad. This is not the case for Ricigliano, Jaffe, or numerous other writers of pedagogical jazz theory.4 Rather, in complete indifference to, ignorance of, or reaction against the common-practice principle that only triads or 1 Ricigliano 1967, 21. 2 A prime example, Berry applies the metaphor of “motion” to explore “Formal processes and element-actions of growth and decline” within different musical domains, in diverse stylistic contexts. Berry 1976, 6 (also see 111–2). An important precedent for Berry’s work in the metaphoric dynamism of harmony and other parameters is found in the writings of Kurth – particularly in his conceptions of “sensuous” and “energetic” harmony. -

Leihmaterial Bote & Bock

Leihmaterial Bote & Bock - Stand: November 2015 - Komponist / Titel Instrumentation Komp. / Dauer Aa, Michel van der 2 After Life B 2S,M,A,2Ba; 2005-06/ 95' Oper nach dem Film von Hirokazu Kore-Eda 0.1.1.BKl.0-0.1.0.1-Org(=Cemb)-Str(3.3.3.2.2); 2009 elektr Soundtrack; Videoprojektionen 1 The Book of DisquietB 1.0.1.1-0.1.0.0-Perc(1): 2008 75' Musiktheater für Schauspieler, Ensemble und Film Vib/Glsp/3Metallstücke/Cabasa/Maracas/Egg Shaker/ 4Chin.Tomt/grTr/Bambusglocken/Ratsche/Peitsche(mi)/ HlzBl(ti)/2Logdrum/Tri(ho)/2hgBe-4Vl.3Va.2Vc.Kb- Soundtrack(Laptop,1Spieler)-Film(2Bildschirme) 0 Here [enclosed] B 0.0.1.1-0.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(6.6.6.4.2)- 2003 17' für Kammerorchester und Soundtrack Soundtrack(Laptop, 1Spieler); Theaterobjekt K Here [in circles] B Kl.BKl.Trp-Perc(1)-Str(1.1.1.1.1); 2002 15' für Sopran und Ensemble kl Kassetten-Rekorder (z.B. Sony TCM-939) 0 Here [to be found]B 0.0.1.1-0.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(6.6.6.4.2)- 2001 18' für Sopran, Kammerorchester und Soundtrack Soundtrack(Laptop, 1 Spieler) Here Trilogy B 2001-03 50' siehe unter Here [enclosed], Here [in circles], Here [to be found] F Hysteresis B Fg-Trp-Perc(1)-Str*; Soundtrack(Laptop,1 Spieler); 2013 17' für Solo-Klarinette, Ensemble und Soundtrack *Streicher: 1.0.1.1.1 (alle vertärkt) oder 4.0.3.2.1 oder 6.0.5.4.2; Kb mit tiefer C-Saite 2 Imprint B 2Ob-Cemb-Str(4.4.3.2.1); 2005 14' für Barock-Orchester Portativ-Orgel zu spielen vom Solo-Violinisten; Historische Instrumente (415 Hz Stimmung) oder moderne Instrumente in Barock-Manier gespielt 1 Mask B 1.0.1.0-1.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(1.1.1.1.1)- -

The Most Common Orchestral Excerpts for the Horn: a Discussion of Performance Practice

The most common orchestral excerpts for the horn: a discussion of performance practice by Shannon L. Armer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Music in the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Dr. J. deC Hinch Pretoria January 2006 © University of Pretoria ii ABSTRACT This study describes in detail the preparation that must be done by aspiring orchestral horn players in order to be sufficiently ready for an orchestral audition. The general physical and mental preparation, through to the very specific elements that require attention when practicing and learning a list of orchestral excerpts that will be performed for an audition committee, is investigated. This study provides both the necessary tools and the insight borne of a number of years of orchestral experience that will enable a player to take a given excerpt and learn not only the notes and rhythms, but also discern many other subtleties inherent in the music, resulting in a full understanding and mastery thereof. Ten musical examples are included in order to illustrate the type of additional information that a player must gain so as to develop an in-depth knowledge of an excerpt. Three lists are presented within the text of this study: 1) a list of excerpts that are most commonly found at auditions, 2) a list of those excerpts that are often included and 3) other excerpts that have been requested but are not as commonly found. Also included is advice regarding the audition procedure itself, a discussion of the music required for auditions, and a guide to the orchestral excerpt books in which these passages can be found. -

Theory Placement Examination (D

SAMPLE Placement Exam for Incoming Grads Name: _______________________ (Compiled by David Bashwiner, University of New Mexico, June 2013) WRITTEN EXAM I. Scales Notate the following scales using accidentals but no key signatures. Write the scale in both ascending and descending forms only if they differ. B major F melodic minor C-sharp harmonic minor II. Key Signatures Notate the following key signatures on both staves. E-flat minor F-sharp major Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) III. Intervals Identify the specific interval between the given pitches (e.g., m2, M2, d5, P5, A5). Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ Note: the sharp is on the A, not the G. Interval: ________ ________ ________ ________ ________ IV. Rhythm and Meter Write the following rhythmic series first in 3/4 and then in 6/8. You may have to break larger durations into smaller ones connected by ties. Make sure to use beams and ties to clarify the meter (i.e. divide six-eight bars into two, and divide three-four bars into three). 2 Sample Graduate Theory Placement Examination (D. Bashwiner, UNM, 2013) V. Triads and Seventh Chords A. For each of the following sonorities, indicate the root of the chord, its quality, and its figured bass (being sure to include any necessary accidentals in the figures). For quality of chord use the following abbreviations: M=major, m=minor, d=diminished, A=augmented, MM=major-major (major triad with a major seventh), Mm=major-minor, mm=minor-minor, dm=diminished-minor (half-diminished), dd=fully diminished. Root: Quality: Figured Bass: B. -

Burkholder/Grout/Palisca, Eighth Edition, Chapter 35 38 Chapter 35

38 17. After WW II, which group determined popular music styles? Chapter 35 Postwar Crosscurrents 18. (910) What is the meaning of generation gap? 1. (906) What is the central theme of Western music history since the mid-nineteenth century? 19. The music that people listened to affected their ____ and _______. 2. What are some of the things that pushed this trend? 20. What is the meaning of charts? 3. Know the definitions of the boldface terms. 21. What is another term for country music? What are its sources? 4. What catastrophic event occurred in the 1930s? 40s? 5. (907) Who are the existentialist writers? 22. (911) Why was it valued? 6. What political element took control of eastern Europe? 23. Describe the music. 7. What is the name of the political conflict? What are the names of the two units and who belongs to each? 24. What are the subclassifications? 8. What's the next group founded in 1945? 25. Name the stars. 9. What are the next wars? What is the date of the moon landing? 26. What's the capital? Theatre? 27. What's the new style that involves electric guitars? City? 10. TQ: What is a baby boom? G.I. Bill? Musician? 28. What phrase replaced "race music." 11. (908) Know the meaning of 78-rpm, LP, "45s." 12. Know transistor radio and disc jockey. 29. What comprised an R&B group? 13. When were tape recorders invented? Became common? 14. (909) When did India become independent? 30. What structure did they use? 15. Name the two figures important for the civil rights 31. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

Perceived Triad Distance: Evidence Supporting the Psychological Reality of Neo-Riemannian Transformations Author(S): Carol L

Yale University Department of Music Perceived Triad Distance: Evidence Supporting the Psychological Reality of Neo-Riemannian Transformations Author(s): Carol L. Krumhansl Source: Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 42, No. 2, Neo-Riemannian Theory (Autumn, 1998), pp. 265-281 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of the Yale University Department of Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/843878 . Accessed: 03/04/2013 14:34 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Duke University Press and Yale University Department of Music are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Music Theory. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.84.127.82 on Wed, 3 Apr 2013 14:34:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PERCEIVED TRIAD DISTANCE: EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE PSYCHOLOGICAL REALITY OF NEO-RIEMANNIAN TRANSFORMATIONS CarolL. Krumhansl This articleexamines two sets of empiricaldata for the psychological reality of neo-Riemanniantransformations. Previous research (summa- rized, for example, in Krumhansl1990) has establishedthe influence of parallel, P, relative, R, and dominant, D, transformationson cognitive representationsof musical pitch. The present article considers whether empirical data also support the psychological reality of the Leitton- weschsel, L, transformation.Lewin (1982, 1987) began workingwith the D P R L family to which were added a few other diatonic operations. -

Reconsidering Pitch Centricity Stanley V

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 2011 Reconsidering Pitch Centricity Stanley V. Kleppinger University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the Music Commons Kleppinger, Stanley V., "Reconsidering Pitch Centricity" (2011). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 63. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/63 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Reconsidering Pitch Centricity STANLEY V. KLEPPINGER Analysts commonly describe the musical focus upon a particular pitch class above all others as pitch centricity. But this seemingly simple concept is complicated by a range of factors. First, pitch centricity can be understood variously as a compositional feature, a perceptual effect arising from specific analytical or listening strategies, or some complex combination thereof. Second, the relation of pitch centricity to the theoretical construct of tonality (in any of its myriad conceptions) is often not consistently or robustly theorized. Finally, various musical contexts manifest or evoke pitch centricity in seemingly countless ways and to differing degrees. This essay examines a range of compositions by Ligeti, Carter, Copland, Bartok, and others to arrive at a more nuanced perspective of pitch centricity - one that takes fuller account of its perceptual foundations, recognizes its many forms and intensities, and addresses its significance to global tonal structure in a given composition. -

Citymac 2018

CityMac 2018 City, University of London, 5–7 July 2018 Sponsored by the Society for Music Analysis and Blackwell Wiley Organiser: Dr Shay Loya Programme and Abstracts SMA If you are using this booklet electronically, click on the session you want to get to for that session’s abstract. Like the SMA on Facebook: www.facebook.com/SocietyforMusicAnalysis Follow the SMA on Twitter: @SocMusAnalysis Conference Hashtag: #CityMAC Thursday, 5 July 2018 09.00 – 10.00 Registration (College reception with refreshments in Great Hall, Level 1) 10.00 – 10.30 Welcome (Performance Space); continued by 10.30 – 12.30 Panel: What is the Future of Music Analysis in Ethnomusicology? Discussant: Bryon Dueck Chloë Alaghband-Zadeh (Loughborough University), Joe Browning (University of Oxford), Sue Miller (Leeds Beckett University), Laudan Nooshin (City, University of London), Lara Pearson (Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetic) 12.30 – 14.00 Lunch (Great Hall, Level 1) 14.00 – 15.30 Session 1 Session 1a: Analysing Regional Transculturation (PS) Chair: Richard Widdess . Luis Gimenez Amoros (University of the Western Cape): Social mobility and mobilization of Shona music in Southern Rhodesia and Zimbabwe . Behrang Nikaeen (Independent): Ashiq Music in Iran and its relationship with Popular Music: A Preliminary Report . George Pioustin: Constructing the ‘Indigenous Music’: An Analysis of the Music of the Syrian Christians of Malabar Post Vernacularization Session 1b: Exploring Musical Theories (AG08) Chair: Kenneth Smith . Barry Mitchell (Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance): Do the ideas in André Pogoriloffsky's The Music of the Temporalists have any practical application? . John Muniz (University of Arizona): ‘The ear alone must judge’: Harmonic Meta-Theory in Weber’s Versuch . -

MTO 20.2: Wild, Vicentino's 31-Tone Compositional Theory

Volume 20, Number 2, June 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Genus, Species and Mode in Vicentino’s 31-tone Compositional Theory Jonathan Wild NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.wild.php KEYWORDS: Vicentino, enharmonicism, chromaticism, sixteenth century, tuning, genus, species, mode ABSTRACT: This article explores the pitch structures developed by Nicola Vicentino in his 1555 treatise L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica . I examine the rationale for his background gamut of 31 pitch classes, and document the relationships among his accounts of the genera, species, and modes, and between his and earlier accounts. Specially recorded and retuned audio examples illustrate some of the surviving enharmonic and chromatic musical passages. Received February 2014 Table of Contents Introduction [1] Tuning [4] The Archicembalo [8] Genus [10] Enharmonic division of the whole tone [13] Species [15] Mode [28] Composing in the genera [32] Conclusion [35] Introduction [1] In his treatise of 1555, L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (henceforth L’Antica musica ), the theorist and composer Nicola Vicentino describes a tuning system comprising thirty-one tones to the octave, and presents several excerpts from compositions intended to be sung in that tuning. (1) The rich compositional theory he develops in the treatise, in concert with the few surviving musical passages, offers a tantalizing glimpse of an alternative pathway for musical development, one whose radically augmented pitch materials make possible a vast range of novel melodic gestures and harmonic successions. -

Viewed by Most to Be the Act of Composing Music As It Is Being

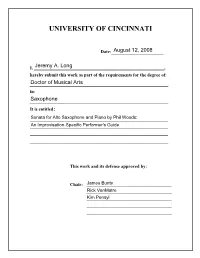

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods: An Improvisation-Specific Performer’s Guide A doctoral document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By JEREMY LONG August, 2008 B.M., University of Kentucky, 1999 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 2002 Committee Chair: Mr. James Bunte Copyright © 2008 by Jeremy Long All rights reserved ABSTRACT Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods combines Western classical and jazz traditions, including improvisation. A crossover work in this style creates unique challenges for the performer because it requires the person to have experience in both performance practices. The research on musical works in this style is limited. Furthermore, the research on the sections of improvisation found in this sonata is limited to general performance considerations. In my own study of this work, and due to the performance problems commonly associated with the improvisation sections, I found that there is a need for a more detailed analysis focusing on how to practice, develop, and perform the improvised solos in this sonata. This document, therefore, is a performer’s guide to the sections of improvisation found in the 1997 revised edition of Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by Phil Woods. -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ......................................................................................