Pretext and Subversion: Lucrezia Marinella's Essortationi Alle Donne (1645)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01-ALEA Program April 2, 2018-II

F o r t i e t h S e a s o n THE NEXT ALEA III EVENTS 2 0 1 7 - 2 0 18 Music for Two Guitars Monday, April 2, 2018, 8:00 p.m. Community Music Center of Boston 34 Warren Avenue, Boston, MA 02116 Free admission ALEA III Alexandra Christodimou and Yannis Petridis, guitar duo Piano Four Hands Thursday, April 19, 2018, 8:00 p.m. TSAI Performance Center - 685 Commonwealth Avenue Theodore Antoniou, Free admission Music Director Works by Antoniou, Gershwin, Khachaturian, Paraskevas, Piazzolla, Rodriguez, Ravel, Rachmaninov, Villoldo Contemporary Music Ensemble in residence at Boston University since 1979 Laura Villafranca and Ai-Ying Chiu, piano 4 hands Celebrating 1,600 years of European Music Wednesday, May 9, 2018, 8:00 p.m. Old South Church – 645 Boylston Street, Boston, MA 02116 Music for Two Guitars Free admission On the occasion on the Europe Day 2018. Curated by CMCB faculty members Works from Medieval Byzantine and Gregorian Chant, through Bach Santiago Diaz and Janet Underhill to Skalkottas, Britten, Messiaen, Ligeti, Sciarrino and beyond. ALEA III 2018 Summer Meetings Community Music Center of Boston August 23 – September 1, 2018 Allen Hall Island of Naxos, Greece 34 Warren Avenue, Boston A workshop for composers, performers and visual artists to present their work and collaborate in new projects to be featured in 2018, 2019 and 2020 events. Daily meetings and concerts. Monday, April 2, 2018 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD OF ADVISORS I would like to support ALEA III. Artistic Director Mario Davidovsky Theodore Antoniou Spyros Evangelatos During our fortieth Please find enclosed my contribution of $ ________ Leonidas Kavakos 2017-2018 season, the need payable to ALEA III Assistant to the Artistic Director Milko Kelemen for meeting our budget is Alex Κalogeras Oliver Knussen very critical. -

Yarın: Muhakemesi B~Gün Eona Ermiıtir

Yirmi yedinci yıl No. 7350 Cumartesi 6 Teşrinisani 937 Jap.on gençleri, Tokyoda lngiliz sefa· rethanesi önOnde nümayiş y~ptılare Şanhhay, 5 (Radyo) - Dün Sanghay, 5 (Radyo) - (Su· gece sabaha kadar devam eden çeo) nehrinin öbür sahıline geç• şiddetli ve büyük bir muhare mek istiyen Japonlar, Çin top nıi lisanile böyle bir talebi iler~ Berlin, 5 (Radyo) - Tokyo- Oral ve Tıansiberyen demir· '""\ beden sonra Japon kuvvetleri, çularının şiddetli hücumuna ma sürmemiş, müstemleke taleplerı dan alınan haberlere göre, dış yolları, asker ve mühimmat se~- Sevid Rıza Çin cebhesini yarmışlar ve So ruz kaldıklarından gerilemişlerdir. ikinci derecedeki şahısların ağ· Mongolistanda gece gündüz Rus kiyatile meşguldür. Bu iki hatte, 'J çeo nehrinin öte ta r afına geç• Bu hücum neticesinde Japon zmda veyahut gazete sütunla- kuvvetlen tahşid edilmektedir. - Sonu 70 unca sa/ti/ede - ·Ve arkadaflarının meğe muvaffak olmuşlardır. - Sonu 1O uncu sayfada • rmda gevelenip durmuştur. Almanlar pratik adamlar olduk 9 lar konferansı idamları istendi ları için Versay muahedesile el· letanbul, !l (Roıu•i) - Seyid lerinden alman bütün haklarını Rıza 11ergerdeai ile arkadaılannıo Yarın: muhakemesi b~gün eona ermiıtir. birden istemek gibi çıkmaz bir Müddeiumumi iddiaoameıioi yola girmekten kemalidikkatle okumuı ve Seyid Rıza ile arkadao ictinap ettiler. Geçenlerde Bay lanoıo idamlanoı ietemiıur. Maç ve güreşler var ~~~~---~~~~- Mussoliniye atfen ileri 6Ürülen K o nfar an s, Salı günü tekrar toplanacak ve Sergerdeler ikinci celııede mfl· muvaffakıyet sımna tamamile dafaalanoı yapmışlar ve bermutad Güreşlerde iki Yunanlı ile iki uyarak istiyeceklerini hep birer Japonyanın vereceği cevabı tetkik edecektir. kaodınldıklarım aöylemiılerdir. Mahkemenin, pazarteıi giloü birer istediler ve onu isterken - miyerek, konferanstan ayrılaca karan tefhim edeceği ıöyleniyor. Türk pehlivanı karşılaşacak! ğını bildirmiştir. -

Future of Equality Report

Future of Equality She Talks #1 Report Women’s rights advocates from the Western Balkans and Turkey gathered virtually to discuss new pathways to gender equality and call for urgent action on 10 September 2020. In total, 51 participants from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo,1 Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Slovenia and Turkey took part in the first She Talks that kicked off a series of regional consultations that will tackle the challenges to achievement of gender equality and transformative change in the lives of women and girls. This series of consultations are organized by the Women's Platform for Development of Serbia in cooperation with UN Women as part of the Support to Priority Actions for Gender Equality project. This project is funded by the European Union. With these discussions, activists for gender equality and women's rights also mark the 25th anniversary of the sign- ing of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, the most visionary and ambitious roadmap set for gender equality. Starting from the commitments accepted under the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action twenty-five years ago, feminists and women’s movement activists considered available analyses of progress in six broad areas: a. gender-based violence; b. economic justice and rights; c. bodily autonomy and sexual and reproductive health and rights; d. feminist action for climate justice; e. technology and innovation for gender equality; and feminist movements and leadership. They further discussed how to tackle region-specific bottlenecks and dead ends and how to bolster feminist solidarity and collaboration within the region. She Talks seek to feed voices and ideas of women from the Western Balkans and Turkey into the Generation Equality Forum, a civil society–centered, global gathering for gender equali- ty, convened by UN Women and co-hosted by the governments of Mexico and France. -

International Conference Nursing – Caring for People in Contemporary

International Journal of Caring Sciences April 2019 Supplement 1 Page |1 International Conference Nursing – Caring for People in Contemporary Societies April 5th – 6th 2019 Frederick University Nicosia Cyprus Final Programme and Conference Proceedings Organized by: Nursing Department. Frederick University, Nicosia Cyprus Co-organizers: Nursing Department of Peloponnese Sparta Greece Nurses and Midwives Association of Cyprus International Journal of Caring Sciences Scientific Committee: President Prof. Despina Sapountzi-Krepia, Cyprus Members: Assist. Prof. Foteini Tzavella, Greece Prof. Maritsa Gourni, Cyprus Assist. Prof. Andrea Paola Rojas Gil, Greece Prof. Panagiotis Prezerakos, Greece Assist. Prof. Areti Tsaloglidou, Greece Prof. Lambrini Kourkouta, Greece Assist. Prof. Theodora Kafkia, Greece Prof. Alexandra Dimitriadou, Greece Assist. Prof. Evanthia Sakellari, Greece Prof. Sophia Zyga, Greece Assist. Prof. Anastasios Tzenalis, Greece Prof. Ruth Northway, UK Senior Lecturer Despena Andrioti Bygvraa, Denmark Assoc. Prof. Leena Honcauvo, Norway Lecturer Alexis Samoutis, Cyprus Assoc. Prof. George Charalambous, Cyprus Lecturer Evanthia Asimakopoulou, Cyprus Assoc. Prof. Georgios I. Panoutsopoulos, Greece Dr Vassiliki Krepia, Greece Assoc. Prof. Maria Lavdaniti, Greece Dr Michael Kourakos, Greece Assoc. Prof. Eygenia Minasidou, Greece Ioannis Dimitrakopoulos, MSc, Cyprus Assist. Prof. George Miltiadou, Cyprus Vassiliki Diamantidou, MD, MSc, Greece Assist. Prof. Alexandros Argyriadis, Cyprus Savvas Karasavvidis, MSc, Greece Assist. Prof. Maria Pantelidou, Cyprus Ioannis Leontiou, MSc, Cyprus Assist. Prof. Petros Kolovos, Greece Aristeidis Chorattas, MSc, Cyprus Assist. Prof. Aspasia Panagiotou, Greece www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org International Journal of Caring Sciences April 2019 Supplement 1 Page |2 Organizing Committee: President: Ioannis Dimitrakopoulos, Cyprus Members Dr Vasileios Dedes, Greece Prof. Despina Sapountzi-Krepia, Cyprus Georgia Kouri, Greece Prof. Lambrini Kourkouta, Greece Nikolaos Mitropoulos, Greece Prof. -

Catalogo De Canciones 15/04/2021 16:31:14

CATALOGO DE CANCIONES 15/04/2021 16:31:14 IDIOMA: Griego CODIGO INTERPRETE TITULO EL32131 ADAMANTIDIS MA POU NA PAO EL32202 AGATHONAS IAKOVIDIS PENTE MAGES STON PEREA EL32155 ANDRIANA MPAMPALI MIRA MOU EGINES EL32083 ANNA VISSI EVERYTHING EL32097 ANNA VISSI GAZI EL32156 ANNA VISSI MONI MOU EL32211 ANTONIS REMOS POIA NOMIZEIS POS EISAI EL32093 ANTZELA DIMITRIOU FOTIA STA SAVATOVRADA EL32122 ANTZELA DIMITRIOU KLISE FOTA EL32185 ANTZELA DIMITRIOU OI XORISMENOI DEN GIORTAZOUNE POTE EL32104 AVGERINOS GIA TA MATIA TOU KOSMOU EL32019 BANOU AN EINAI I AGAPI EL32265 C-REAL THA PERIMENO EL32194 DANTIS PAI I AGAPI MOU EL32043 DIMITRA GALANI DEN EISAI EDO EL32139 DIONISIOU ME SKOTOSE GIATI TIN AGAPOUSA EL32073 EIRINI MERKOURI EMATHA NA ZO XORIS ESENA EL32024 ELENA PAPARIZOU ANAPANTITES KLISIS EL32132 ELENA PAPARIZOU MAMBO EL32125 ELLI KOKKINOU KOSMOTHEORIA EL32249 F. NICOLAOU STO ADIO MOU PAKETO EL32314 GARBI XAMENA EL32157 GARMBI MONI MOU EL32205 GARMBI PES TO MENA FILI EL32066 GIANNIS VARDIS EIPES POS EL32183 GIORGOS SARRIS OI NTALIKES EL32116 GIORGOS TSALIKIS KAPOS ETSI EL32161 GLIKERIA MOU FAGES OLA TA DAKTILIDIA EL32052 GONIDIS DEN THA MATHIS POTE EL32086 GONIDIS EXO PETAXI MAZI SOU EL32147 GONIDIS MIA AGAPI DEN TELIONI EL32130 IPOGIA REVMATA M'ARESEI NA MIN LEO POLLA EL32064 ISAIAS MATIMPA EIMAI KALA, KAI S'AGAPO EL32053 KARAFOTIS DEN THA MINO EL32151 KARRAS MIN ANISIXIS EL32221 KATERINA KOUKA RIXE STO KORMI MOU SPIRTO EL32146 KATSIMIXA MI GIRISEIS EL32220 KATSIMIXA RITA RITAKI EL32032 KAZANTZIDIS APONI ZOI EL32309 KAZANTZIDIS VRADIAZI EL32078 -

Popular Music and Narratives of Identity in Croatia Since 1991

Popular music and narratives of identity in Croatia since 1991 Catherine Baker UCL I, Catherine Baker, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated / the thesis. UMI Number: U592565 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592565 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis employs historical, literary and anthropological methods to show how narratives of identity have been expressed in Croatia since 1991 (when Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia) through popular music and through talking about popular music. Since the beginning of the war in Croatia (1991-95) when the state media stimulated the production of popular music conveying appropriate narratives of national identity, Croatian popular music has been a site for the articulation of explicit national narratives of identity. The practice has continued into the present day, reflecting political and social change in Croatia (e.g. the growth of the war veterans lobby and protests against the Hague Tribunal). -

Future of Equality, She Talks Joint Summary Report from Sub-Regional Wester Balkans and Turkey Consultations

Future of equality, She talks joint summary report from sub-regional Wester Balkans and Turkey consultations Introduction Year 2020 is very significant millstone year for the women’s rights. It is 25 years anniversary of Beijing Declaration and adoption of Beijing Platform for Action. It was supposed to be a transformative year for gender equality. The Generation Equality Forums (GEF)1 in Paris and Mexico City, expected for 2020 as an intergenerational and intersectional gathering for gender equality with a leadership of civil society and support from UN Women, France and Mexico, is re- scheduled for 2021. Forums are aimed to create a renewed momentum for women’s rights and to accelerate progress towards gender equality and leaving no-one behind. The GEF launch six Action Coalitions: Gender-Based Violence; Economic justice and rights; Bodily autonomy and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR); Feminist action for climate justice; Technology and innovation for gender equality and Feminist movements and leadership. The Action Coalitions represent innovative models of multi-stakeholder partnership, involving governments, civil society, private sector, parliamentarians, trade unions and other stakeholders, who share a common goal to accelerate action on a critical thematic area of concern. Each Action Coalition will develop a set of concrete, ambitious and transformative actions that the members of the Action Coalition will take, with time and resource commitments, for implementation between 2020-2025 in order to achieve immediate and irreversible progress towards gender equality. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic that started worldwide in March 2020 and rescheduling the foreseen Generation Equality Forums (GEF) for 2021, there was a huge risk to lose a momentum of the wide social mobilization and weakening accountability for gender equality commitments. -

1963-1964 Dersyılında S

E R G ü n ü 23 ısa milietvekj. Haziran BASIMEVİ GlRNE YOLU 1963 LEFKOŞE 1 Program . TEL: 73838 SAYFA :det Üruğ-Un SA Y I: 58 SAHİBİ: HİKMET AFİF MAPOLAR FİATI: 15 MU Pazar z ve Ses Ekibi Kadın ıı ■ ■■ îrtip Heyeti 1963-1964 Ders Yılında S,» optu m m * Moskova - Rus kozmo notları Büyük Kremlin Sa lıılniııiııiıii!,ıL|ll| <l|lı|., rayında tertibedilen bir tü Okul ücretleri Artırıldı rende hazır bulunmuşlar m 4. Okul öğrencilerinden ve Başkan Leonid Brez- Kıbrıs Türk Maarif Mü X alınacak yeni okuma üc- hnev’den mükâfatlannı al dUrlüğü, 1963 • 64 ders yı ı a Bunun yanmda Spor, Sıhhiye ve T jetlerinden. Müdürlükle*----------— ----------- IIIIŞImışlardır.cII U1I . İİki M ıkozmonotu v u ^ ı ı ı u ı ı v m lı zarfında alınacak “oku I 'rin tanzim edecekleri bir karşıiamak için Kızıl Mey ma ücreti” hakkında dün Daktilo gibi ücretler almmıyacak II i______yazısı ile _ öğrenci ırûlilarininvelilerinin danda. mahşerîı lbir.* ikalaba___1 ~ U ^ bir açıklama yapmıştır. haberdar edilmesini ve bu lık toplanmıştı. I Müdürlükçe yayınlanan X ***** ************* yazıda 1962 63 ders yılı Sovyet lideri yaptığı bir Türk Maarif Bülteninde f lerine duyurulmasını iste na nazaran tevhit edilmiş konuşmada, en son başarı bu konuda Geniş bilgi ve rında yılda: 14 lira. yeni ücretlerde Görülecek ların, Sovyet Komünist rilmekte ve ücretlerin ar b) Köy Ortaokullarında di: 2. 1962 - 63 ders yılında |üczi artışın; Partisinin barış ve işbirli tırıldığı yazılmaktadır. yılda 11 lira. arlaSm ı öğrencilerden duhuliye dı a) Okulumuzun öğre ğine inandığını, barış için Bu duruma Göre “oku c) Ticaret Liseleri ve Li tim araç ve Gereçlerinin anlaşmaya hazır olduğu ciponlu kadın ma ücreti” aşağıda Göste selere bağlı Ticaret Bö şında alınmakta olan spor j modernleştirilmesi, nu, bunun herhanGi bir za rildiği şekilde olacaktır, lümlerinde yılda 15 lira. -

“Dracula in Iceland”. an Interview with Marinella Lorinczi

“Dracula in Iceland”. An Interview with Marinella Lorinczi ML. Thank you for the kind appreciation. I have the deep convinction that a genuine, really good scholar of Bram Stoker’s most famous novelDracula should investigate the whole literary production of this interesting writer, and connect the novel with his other narratives, both short and long. It is not entirely my case, I must confess, although I tried to compare Dracula with other two novels of his, i.e. The Lady of the Shroud and The Jewel of Seven Stars. However, I can be excused, because my main research subjects – as you mentioned – are not English literature or literature of the Victorian age. I did not begin my Dracula studies reading in English, but in Romanian and Italian. After that beginning, I was obliged not to avoid the English language, therefore my initial, very poor knowledge of this language improved and now I am able to read, understand, and study essays as well as works of fictional literature. All this thanks to Dracula… A nearly unknown Dracula to me, at the beginning, because in Romania – my country of birth -Stoker’s novel has no special significance, and only the historical person has, who lived in the XV century – he is called normally Vlad Tepes, that is, Vlad the Impaler – and is best known from history textbooks (as voivode, that is governer of Wallachia, now South Romania). Therefore my first and almost casual glance was at the historical figure, in the historical documents regarding him, and not at the novel. And this kind of interest fits with the interests of the philologist in the wider sense. -

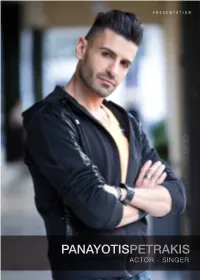

P R E S E N T a T I

PRESENTATIONPRESENTATION | 1 Panayotis Petrakis has worked as a diverse and sought after actor/singer/dancer in TV, theatre and music for almost 20 years. A combination of talent, impeccable professionalism and an infectious personality has ensured him constant work and an exemplary reputation. www.panayotispetrakis.com [email protected] PRESENTATION | 1 HEIGHT: 1,85M | WEIGHT: 82KG | EYES: DARK BROWN | HAIR: DARK BROWN | SINGING VOICE: BARITONE PRESENTATION | 3 Actor - Singer Panayotis Petrakis was born in Athens. Whilst in drama school, he began training alongside inter- nationally renowned baritone Kostas Paskalis1, ultimately earning the acclaimed Fulbright Scholarship2 to continue his training in NY. Panayotis has worked successfully in TV, theatre and music for almost 20 years, collaborating with some of Greece’s most acclaimed directors, musicians, actors and recording artists at the biggest venues, concert halls and TV channels. In 2008 he received nationwide recognition for his role in the No1 rated, prime time continuing drama “Secrets of Eden”3. The show achieved ratings up to 52% and 2 million viewers for 3 consecutive years and was sold to 8 countries. His theatre credits include leading roles in productions as diverse as: “Saturday Night Fever, the musical”, “Fun- ny Girl”, “Querelle de Brest” and “Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, the musical”4 5. Known for his rich baritone voice and soulful renditions, he has collaborated with Greece’s most acclaimed com- posers and song writers like Mikis Theodorakis6 and Mimis Plessas7. In 2011 Panayotis won the celebrity talent TV show “Just the two of us”8; a 14-episode reality singing contest show for a charitable cause, based on BBC’s homonymous production. -

Eurovisie Top1000

Eurovisie 2017 Statistieken 0 x Afrikaans (0%) 4 x Easylistening (0.4%) 0 x Soul (0%) 0 x Aziatisch (0%) 0 x Electronisch (0%) 3 x Rock (0.3%) 0 x Avantgarde (0%) 2 x Folk (0.2%) 0 x Tunes (0%) 0 x Blues (0%) 0 x Hiphop (0%) 0 x Ballroom (0%) 0 x Caribisch (0%) 0 x Jazz (0%) 0 x Religieus (0%) 0 x Comedie (0%) 5 x Latin (0.5%) 0 x Gelegenheid (0%) 1 x Country (0.1%) 985 x Pop (98.5%) 0 x Klassiek (0%) © Edward Pieper - Eurovisie Top 1000 van 2017 - http://www.top10000.nl 1 Waterloo 1974 Pop ABBA Engels Sweden 2 Euphoria 2012 Pop Loreen Engels Sweden 3 Poupee De Cire, Poupee De Son 1965 Pop France Gall Frans Luxembourg 4 Calm After The Storm 2014 Country The Common Linnets Engels The Netherlands 5 J'aime La Vie 1986 Pop Sandra Kim Frans Belgium 6 Birds 2013 Rock Anouk Engels The Netherlands 7 Hold Me Now 1987 Pop Johnny Logan Engels Ireland 8 Making Your Mind Up 1981 Pop Bucks Fizz Engels United Kingdom 9 Fairytale (Norway) 2009 Pop Alexander Rybak Engels Norway 10 Ein Bisschen Frieden 1982 Pop Nicole Duits Germany 11 Save Your Kisses For Me 1976 Pop Brotherhood Of Man Engels United Kingdom 12 Vrede 1993 Pop Ruth Jacott Nederlands The Netherlands 13 Puppet On A String 1967 Pop Sandie Shaw Engels United Kingdom 14 Apres toi 1972 Pop Vicky Leandros Frans Luxembourg 15 Power To All Our Friends 1973 Pop Cliff Richard Engels United Kingdom 16 Als het om de liefde gaat 1972 Pop Sandra & Andres Nederlands The Netherlands 17 Eres Tu 1973 Latin Mocedades Spaans Spain 18 Love Shine A Light 1997 Pop Katrina & The Waves Engels United Kingdom 19 Only -

Mimis Plessas

:: SEP 2009 $2.95 6 37 14 22 08 21 Greek Americans to 28 host U. S. House and The New A different kind of Senate Leaders Generation of Leaders Universal Care 16 Lefteris Bournias: 29 Clarinet master of St. Spyridon Youth music East and West Help hellenicare 13 10 22 Mimis Plessas: 19 Maria’s Slate featuring… 34 A Man for All Seasons Beverly Hills event A Special Interview My Summer Journey Returns to New York to support Dina Titus with Elli Kokkinou to the Ionian Village 19 20 Harry Markopolos, 26 38 10 the man who Undefined by their HACC Young Professionals 33 Alexi goes to…Hollywood! uncovered Madoff Circumstance Happy Hour A Musical Issue This issue has a lot of music in it, from the new sensation of singing star Elli Kokkinou, to the :: magazine synthesized mix of old and new by clarinet virtuoso Lefteris Bournias, to the long line of popular music tradition by grand master Mimis Plessas. Editor in Chief: Dimitri C. Michalakis I was born in Chios and still love the klarino more [email protected] than any other instrument. The hairs stand on the :: Features Editor back of my head when I hear the clarinet player Katerina Georgiou tuning up before every wedding and the first dance [email protected] usually has me up on the dance floor immediately—and staying there—as long as the :: klarino is playing. And when a virtuoso of both the old and new like Lefteris Bournias Lifestyle Editor Maria Athanasopoulos begins to play a tsifteli in the old style then I feel no pain and life has become just one [email protected] sweet glendi that I wish would never end.