De-Ranged Global Power and Air Mobility for the New Millennium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NEW VANGUARD 211 US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 ORIGINS OF THE CARRIER AND THE SUPERCARRIER 5 t World War II Carriers t Post-World War II Carrier Developments t United States (CVA-58) THE FORRESTAL CLASS 11 FORRESTAL AS BUILT 14 t Carrier Structures t The Flight Deck and Hangar Bay t Launch and Recovery Operations t Stores t Defensive Systems t Electronic Systems and Radar t Propulsion THE FORRESTAL CARRIERS 20 t USS Forrestal (CVA-59) t USS Saratoga (CVA-60) t USS Ranger (CVA-61) t USS Independence (CVA-62) THE KITTY HAWK CLASS 26 t Major Differences from the Forrestal Class t Defensive Armament t Dimensions and Displacement t Propulsion t Electronics and Radars t USS America, CVA-66 – Improved Kitty Hawk t USS John F. Kennedy, CVA-67 – A Singular Class THE KITTY HAWK AND JOHN F. KENNEDY CARRIERS 34 t USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) t USS Constellation (CVA-64) t USS America (CVA-66) t USS John F. Kennedy (CVA-67) THE ENTERPRISE CLASS 40 t Propulsion t Stores t Flight Deck and Island t Defensive Armament t USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 INDEX 48 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS FORRESTAL, KITTY HAWK AND ENTERPRISE CLASSES INTRODUCTION The Forrestal-class aircraft carriers were the world’s first true supercarriers and served in the United States Navy for the majority of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union. -

The Uss Liberty Story

THE USS LIBERTY STORY The USS Liberty – the most decorated Navy ship (single action) 1 PURPOSE -- The USS Liberty Veterans Association (LVA) has tried for over 45 years to expose the true story of the deliberate Israeli attack on the US S Liberty to the American people through books, news media, movies, and letters to the President of the United States and congressmen. The mission of the LVA is to pursue the publication of the true story. While we have encountered politicians and news m edia personnel who were willing to help, they have been unable to interest their superiors or others in supporting our cause. Due to political correctness, many people believe it is just too risky to say anything negative about Israel. FYI: The USS Li berty is the most decorated US Navy ship in the history of the Navy for a single action. THE ISSUE -- The Israelis and the US Government do not want the truth to be told. It is obvious that they fear that America may be less of a supportive ally if the t ruth were known. The truth of their deeds and the Johnson Administration require an objective and complete investigation. Congress has never officially investigated the attack and so the attack continues to be a cover - up of the worst magnitude. The Hous e has a constitutional mandate to “define and punish Pirates and Felonies committed on the high seas and offenses against the Law of Nations (Article 1, section 8)”. Regarding the Arab/Israeli ’67 War, we believe the operational plan was Operation Cyanide . -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

The Air League Newsletter

The Air League Newsletter Issue 6: November/December 2015 (Photo RAF Crown Copyright 2015) FINAL VULCAN TRIBUTE TO BOMBER COMMAND eteran aircraft of past and present RAF combat missions paid tribute in October to the memory of Bomber Command by performing a spectacular mid-air link-up over Lincolnshire. Tornado GR4 fighter bomber crews, whose colleagues are currently taking part in the campaign against Islamic StateV militants over Iraq, flew in formation with former Cold War V-Bomber, Vulcan XH558, to mark the unveiling of the Bomber Command Memorial spire in Lincoln. A 12 (Bomber) Squadron pilot who flew on the sortie the Falklands in the famous ‘Operation Black Buck’ said: “It was a real privilege to fly one last time with mission to deny the Argentines use of the airfield. such a historic and magnificent aircraft. It was a fitting Vulcan pilot Wing Commander Bill Ramsey (retired), tribute that the RAF’s current bomber, the Tornado who flew the delta-winged icon for nine years, said: “I GR4, escorted the old Vulcan bomber, a once in a am really pleased the RAF and Vulcan To The Sky team lifetime opportunity which we were very proud to be came together to set up a Vulcan and Tornado ‘Past a part of.” and Present’ flight; especially on the occasion of the The RAF Marham-based squadron, which this year dedication of the new Bomber Command Memorial in celebrated its centenary, has a distinguished list of Lincoln that commemorates the service and sacrifice of battle honours including combat operations in Iraq, so many brave people.” being the first GR4 unit to operate in Afghanistan, and In addition to the formation spectacular, October saw a supporting long-range bombing raids against Gaddafi- final farewell tour by XH588 over the weekend of 10th and regime targets in Libya. -

Lessons in Undersea and Surface Warfare from the Falkland Islands Conflict

Beyond the General Belgrano and Sheffield: Lessons in Undersea and Surface Warfare from the Falkland Islands Conflict MIDN 4/C Swartz Naval Science 2—Research Paper Instructor: CDR McComas 8 April 1998 1 Beyond the General Belgrano and Sheffield: Lessons in Undersea and Surface Warfare from the Falkland Islands Conflict 425 miles off the coast of Argentina lie the Falkland Islands, a string of sparsely inhabited shores home to about 1500 people and far more sheep. The Falklands (or the Malvinas, as the Argentineans call them) had been in dispute long before Charles Darwin incubated his theory of evolution while observing its flora and fauna. Spain, France, Britain, and Argentina each laid claim to the islands at some point; ever since 1833, the Falklands have been a British colony, although ever since 1833, the Argentineans have protested the British “occupation.” In April of 1982, an Argentine military dictatorship made these protests substantial with a full-scale invasion of the islands. The British retaliated, eventually winning back the islands by July. Militarily, this entirely unexpected war was heralded as the first “modern” war—a post- World War II clash of forces over a territorial dispute. “Here at last was a kind of war [military planners] recognized”; unlike Vietnam, this was “a clean, traditional war, with a proper battlefield, recognizable opponents in recognizable uniforms and positions, and no messy, scattered civil populations or guerrilla groups to complicate the situation.”1 Here, the “smart” weapons developed over 40 years of Cold War could finally be brought to bear against real targets. Likewise, the conflict provided one of the first opportunities to use nuclear submarines in real combat. -

Hms Sheffield Commission 1975

'During the night the British destroyers appeared once more, coming in close to deliver their torpedoes again and again, but the Bismarck's gunnery was so effective that none of them was able to deliver a hit. But around 08.45 hours a strongly united attack opened, and the last fight of the Bismarck began. Two minutes later, Bismarck replied, and her third volley straddled the Rodney, but this accuracy could not be maintained because of the continual battle against the sea, and, attacked now from three sides, Bismarck's fire was soon to deteriorate. Shortly after the battle commenced a shell hit the combat mast and the fire control post in the foremast broke Gerhard Junack, Lt Cdr (Eng), away. At 09.02 hours, both forward heavy gun turrets were put out of action. Bismarck, writing in Purnell's ' A further hit wrecked the forward control post: the rear control post was History of the Second World War' wrecked soon afterwards... and that was the end of the fighting instruments. For some time the rear turrets fired singly, but by about 10.00 hours all the guns of the Bismarck were silent' SINK the Bismarck' 1 Desperately fighting the U-boat war and was on fire — but she continued to steam to the picture of the Duchess of Kent in a fearful lest the Scharnhorst and the south west. number of places. That picture was left Gneisenau might attempt to break out in its battered condition for the re- from Brest, the Royal Navy had cause for It was imperative that the BISMARCK be mainder of SHEFFIELD'S war service. -

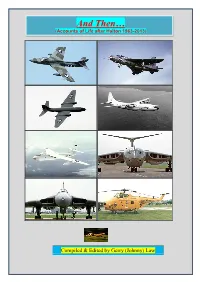

And Then… (Accounts of Life After Halton 1963-2013)

And Then… (Accounts of Life after Halton 1963-2013) Compiled & Edited by Gerry (Johnny) Law And Then… CONTENTS Foreword & Dedication 3 Introduction 3 List of aircraft types 6 Whitehall Cenotaph 249 St George’s 50th Anniversary 249 RAF Halton Apprentices Hymn 251 Low Flying 244 Contributions: John Baldwin 7 Tony Benstead 29 Peter Brown 43 Graham Castle 45 John Crawford 50 Jim Duff 55 Roger Garford 56 Dennis Greenwell 62 Daymon Grewcock 66 Chris Harvey 68 Rob Honnor 76 Merv Kelly 89 Glenn Knight 92 Gerry Law 97 Charlie Lee 123 Chris Lee 126 John Longstaff 143 Alistair Mackie 154 Ivor Maggs 157 David Mawdsley 161 Tony Meston 164 Tony Metcalfe 173 Stuart Meyers 175 Ian Nelson 178 Bruce Owens 193 Geoff Rann 195 Tony Robson 197 Bill Sandiford 202 Gordon Sherratt 206 Mike Snuggs 211 Brian Spence 213 Malcolm Swaisland 215 Colin Woodland 236 John Baldwin’s Ode 246 In Memoriam 252 © the Contributors 2 And Then… FOREWORD & DEDICATION This book is produced as part of the 96th Entry’s celebration of 50 years since Graduation Our motto is “Quam Celerrime (With Greatest Speed)” and our logo is that very epitome of speed, the Cheetah, hence the ‘Spotty Moggy’ on the front page. The book is dedicated to all those who joined the 96th Entry in 1960 and who subsequently went on to serve the Country in many different ways. INTRODUCTION On the 31st July 1963 the 96th Entry marched off Henderson Parade Ground marking the conclusion of 3 years hard graft, interspersed with a few laughs. It also marked the start of our Entry into the big, bold world that was the Royal Air Force at that time. -

Newport Paper 39

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 39 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Influence without Boots on the Ground Seaborne Crisis Response NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O L N L U E E G H E T I VIRIBU OR A S CT MARI VI 39 Larissa Forster U.S. GOV ERN MENT Cover OF FI CIAL EDI TION NO TICE This per spective ae rial view of New port, Rhode Island, drawn and pub lished by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the Amer i can Mem ory On line Map Collec tions: 1500–2003, of the Li brary of Con gress Ge og ra phy and Map Di vi sion, Wash ing ton, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Use of ISBN Pre fix This is the Offi cial U.S. Govern ment edi tion of this pub li ca tion and is herein iden ti fied to cer tify its au then tic ity. ISBN 978-1-935352-03-7 is for this U.S. Gov ern ment Print ing Of fice Of fi cial Edi tion only. The Su per in ten dent of Doc u ments of the U.S. Gov ern ment Print ing Of fice re quests that any re printed edi tion clearly be la beled as a copy of the authen tic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. -

Factors Influencing the Defeat of Argentine Air Power in the Falklands War the Royal Canadian Air Force Journal Vol

FACTORSTHE ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FOrcE JOURNAL INVOL. 1 | NFO. 4 LUENC FALL 2012 ING THE DEFEAT OF ARGENTINE AiR POWER IN THE FALKLANDS WAR BY OffiCER CADET COLIN CLANSEY, CD A column of No. 45 Royal Marine Commandos march toward Port Stanley. Royal Marine Peter Robinson, carrying the Union Jack flag on his backpack as identification, brings up the rear. © Crown copyright. Imperial War Museum (IWM) www.iwm.org.uk/sites/default/files/ public-document/IWM_NonCommercial_Licence_1.pdf 8 Factors Influencing the Defeat of Argentine Air Power in the Falklands War THE ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FOrcE JOURNAL VOL. 1 | NO. 4 FALL 2012 he Argentine defeat in the Falkland takeover, leave, and negotiate to one of defend Islands War was due in part to the over- the islands at all costs. The invasion precipi- whelming superiority of the Royal Navy tated a furious British response in the form of T (RN).1 Most of the action, however, a large-scale military mobilization to retake involved the air powers of the Royal Air Force the Islands. Forced now to adopt a defensive (RAF), the Fleet Air Arm of the RN, the posture, Galtieri unilaterally ordered the Fuerza Aérea Argentina (FAA) or Argentine airlift of the entire 10th Mechanised Brigade Air Force, and the Commando de Aviación and the 3rd Brigade (a total well over 10,000 Naval Argentina (CANA) or Argentine Naval troops) to the Islands for their defence, a Air Command.2 This paper will analyse the drastic increase from the initial 500 used strategy and tactics of the Argentine air forces for the invasion.8 That he took this decision as the most effective arm of the Argentine without consulting his own senior staff shows military junta. -

Fire Safety of Aluminum and Its Alloys

FIRE SAFETY OF ALUMINUM & ITS ALLOYS Acknowledgement The Aluminum Association gratefully acknowledges the efforts of the task group of the Technical Committee on Product Standards in developing this report: Albert Wills, Hydro Brandon Bodily, Arconic Michael Niedzinski, Constellium Aluminum Association Staff This report was authored by the following Aluminum Association staff: Alex Lemmon, Systems Analyst John Weritz, VP Standards & Technology Use of this Information The use of any information contained herein by any member or non-member of The Aluminum Association is entirely voluntary. The Aluminum Association has used its best efforts in compiling the information contained in this paper. While the Association believes that its compilation procedures are reliable, it does not warrant, either expressly or impliedly, the accuracy or completeness of this information, or that it is fit for any particular purpose. The Aluminum Association assumes no responsibility or liability for the use of the information herein. Introduction As one of the most abundant elements on Earth, aluminum can be found in nearly every industry in our modern world. It is light, inexpensive, and easy to work with, making it ideal for a wide variety of applications ranging from electronics and machinery to aircraft structures and tableware. Aluminum is easily combined with several different elements to produce hundreds of alloys with a dizzying array of properties, making aluminum one of the most versatile materials in industry. Depending on the alloying elements, it can be soft and malleable, or exceedingly strong and rigid. It is also prized for its excellent thermal and electrical properties as well as corrosion resistance. -

SA OP15-18 Björklund Gabriel

Självständigt arbete (15hp) Författare Program/Kurs Gabriel Björklund OP SA 15-18 Handledare Antal ord: 11 645 Arash Heydarian Pashakhanlou Beteckning Kurskod 1OP415 Robert Pape och Falklandskriget - En teoriprövande enfallsstudie ABSTRACT: Robert A. Pape, an American political scientist, has created a universally known theory about how to successfully conduct military coercion. In his comprehensive quantitative research from multiple cases of coercion Pape’s conclusion is that the denial strategy of air power is what historically have been working. From his cases where he draws his conclusion there is one case missing. Pape has excluded the case of the Falklands war. According to some researchers, the Falklands war which was won by Great Britain, had a successful outcome due to their utility of air power. This essay aims to test if Papes theory of military coercion has the potential to explain the victory of Great Britain in the Falklands War. By conducting a single case study by means of a qualitative text analysis, the answer is to be found. The results shows that Great Britain mainly used a denial strategy with air powers. The Falklands war could have been predicted by this usage. Although it is a conventional conflict, involving both the navy, army and the airforce, it is hard to believe it was only because of the air powers the war was won. The use of a denial strategy can therefore not explain the victory for Great Britain, but it can be a part of the explanation. Nyckelord Robert Pape, Falklandskriget, tvångsmakt, luftmakt, nekande strategi Gabriel Björklund 2017-06-12 223qrzn Innehållsförteckning 1. -

Avoiding Thucydides' Trap in the Western Pacific Through the Air Domain

DIGITAL-ONLY CADET PERSPECTIVE Avoiding Thucydides’ Trap in the Western Pacific through the Air Domain CADET COLONEL GRANT T. WILLIS Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the United States has arguably exercised the most powerful global military imbalance the world has ever seen. This domination; however, is perceived to be fading in the wake of a new possible contender. The tension and likelihood of conflict between the United States and the People’s Re- public of China (PRC) has risen in recent decades. The inevitability of conflict has taken root in many academic and strategic forums such as 92nd Street Y with Graham Allison and Gen David Petraeus (US Army, retired), The Belfer Center, the US Army War College, and many others. The term “Thucydides’ Trap” has echoed in many discussions among leading strategic, military, intelligence, and political science analysts. This is the notion of one rising power seeking to take its place in the sun by replacing the perceived declining power, which has caused many to fear a new kind of war. Dr. Graham Allison identified 16 scenarios over the past 500 years in which two nations competed within the parameters of “Thucydides’ Trap,” and of those scenarios, 12 have resulted in war.1 At a war likeli- hood of 75 percent, the odds do not seem to be in Washington’s or Beijing’s favor. The Pivot Under the Obama administration, the United States formulated the “Pivot” policy, but these strategic redeployments have not fully taken shape. This strategic shift out of Europe and into the Indo- Pacific have shown the strategic danger China has represented, and many would argue resulted in a swift buildup of Chi- nese military capability unlike ever before.