Exploring the Potential of Hub Airports and Airlines to Convert Stopover Passengers Into Stayover Visitors: Evidence from Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore, July 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Singapore, July 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: SINGAPORE July 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Singapore (English-language name). Also, in other official languages: Republik Singapura (Malay), Xinjiapo Gongheguo― 新加坡共和国 (Chinese), and Cingkappãr Kudiyarasu (Tamil) சி க யரச. Short Form: Singapore. Click to Enlarge Image Term for Citizen(s): Singaporean(s). Capital: Singapore. Major Cities: Singapore is a city-state. The city of Singapore is located on the south-central coast of the island of Singapore, but urbanization has taken over most of the territory of the island. Date of Independence: August 31, 1963, from Britain; August 9, 1965, from the Federation of Malaysia. National Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1); Lunar New Year (movable date in January or February); Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date in February); Good Friday (movable date in March or April); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (June 2); National Day or Independence Day (August 9); Deepavali (movable date in November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date according to the Islamic lunar calendar); and Christmas (December 25). Flag: Two equal horizontal bands of red (top) and white; a vertical white crescent (closed portion toward the hoist side), partially enclosing five white-point stars arranged in a circle, positioned near the hoist side of the red band. The red band symbolizes universal brotherhood and the equality of men; the white band, purity and virtue. The crescent moon represents Click to Enlarge Image a young nation on the rise, while the five stars stand for the ideals of democracy, peace, progress, justice, and equality. -

REPORT of the SIXTH MEETING of the SOUTH EAST ASIA SUB-REGIONAL ADS-B IMPLEMENTATION WORKING GROUP (SEA ADS-B WG/6) Singapore

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION ORGANIZATION ASIA AND PACIFIC OFFICE REPORT OF THE SIXTH MEETING OF THE SOUTH EAST ASIA SUB-REGIONAL ADS-B IMPLEMENTATION WORKING GROUP (SEA ADS-B WG/6) Singapore, 24 to 25 February 2011 Table of Contents HISTORY OF THE MEETING Page Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... i-1 Attendance ........................................................................................................................................... i-1 Opening of the Meeting ....................................................................................................................... i-1 Language and Documentation ............................................................................................................. i-1 SUMMARY OF DISCUSSIONS Agenda Item 1: Adoption of Agenda ...................................................................................................... 1 Agenda Item 2: Review the outcome of the ADS-B SITF/9, APANPIRG/21 on ADS-B ..................... 1 Agenda Item 3: Review Terms of Reference .......................................................................................... 3 Agenda Item 4: Updating States’ activities and mandates issued ........................................................... 4 Agenda Item 5: Review of sub-regional implementation ....................................................................... 6 - Near-term implementation plan, including operational -

Singapore Changi Airport Preparation for & Experience with the A380

Singapore Changi Airport Preparation For & Experience With the A380 Mr Andy YUN Assistant Director (Apron Control Management Service / Safety) Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore Presentation Outline 1. Infrastructure Upgrade o Runway o Taxiway o Apron o Aerobridge o Baggage Handling o Gate Holdroom 2. New Handling Equipment 3. Ground Working Group 4. Training of Operators 5. Trial Flights & Challenges 2 1. Infrastructure Upgrade 3 InfrastructureInfrastructure UpgradeUpgrade Planning ahead to serve the A380. • Changi Airport was the launch pad for the inaugural A380 commercial flight. • Planning started as early as the late 1990s. • New infrastructure designed to provide high levels of safety, efficiency and service for A380 operation. • Existing infrastructure was upgraded at a total cost of S$60 million. Airfield Infrastructure • Upgrade to meet international standards for safe and efficient operation of the bigger aircraft. Passenger Terminals • Increase processing capacity, holding and circulation spaces within the terminals to cater to larger volume of passengers. 4 InfrastructureInfrastructure UpgradeUpgrade -- Airfield Airfield Airfield Separation Distances • Changi’s runways, taxiways and airfield objects are designed with adequate safety separation to meet A380 requirements. 200m >101m 57.5m 60m 30m 30m Runway Taxiway Taxiway Object 5 InfrastructureInfrastructure UpgradeUpgrade -- Runway Runway Runway Length and Width • Changi’s 4km long by 60m wide runways exceed A380 take-off and landing requirements. Runway Shoulders • Completed -

Major Milestones

Major Milestones 1929 • Singapore‟s first airport, Seletar Air Base, a military installation is completed. 1930 • First commercial flight lands in Singapore (February) • The then colonial government decides to build a new airport at Kallang Basin. 1935 • Kallang Airport receives its first aircraft. (21 November) 1937 • Kallang Airport is declared open (12 June). It goes on to function for just 15 years (1937– 1942; 1945-1955) 1951 • A site at Paya Lebar is chosen for the new airport. 1952 • Resettlement of residents and reclamation of marshy ground at Paya Lebar commences. 1955 • 20 August: Paya Lebar airport is officially opened. 1975 • June: Decision is taken by the Government to develop Changi as the new airport to replace Paya Lebar. Site preparations at Changi, including massive earthworks and reclamation from the sea, begin. 1976 • Final Master Plan for Changi Airport, based on a preliminary plan drawn up by then Airport Branch of Public Works Department (PWD), is endorsed by Airport Consultative Committee of the International Air Transport Association. 1977 • May: Reclamation and earthworks at Changi is completed. • June: Start of basement construction for Changi Airport Phase 1. 1979 • August: Foundation stone of main Terminal 1 superstructure is laid. 1981 • Start of Phase II development of Changi Airport. Work starts on Runway 2. • 12 May: Changi Airport receives its first commercial aircraft. • June: Construction of Terminal 1 is completed. • 1 July: Terminal 1 starts scheduled flight operations. • 29 December: Changi Airport is officially declared open. 1983 • Construction of Runway 2 is completed. 1984 • 17 April: Runway 2 is commissioned. • July: Ministry of Finance approves government grant for construction of Terminal 2. -

Chapter 1: Introduction and Background

A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF AIR HUBS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA HAN SONGGUANG (B. Soc. Sci. (Hons.)), NUS A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2007 A Geographical Analysis of Air Hubs in Southeast Asia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It seemed like not long ago when I started out on my undergraduate degree at the National University of Singapore and here I am at the conclusion of my formal education. The decision to pursue this Masters degree was not a straightforward and simple one. Many sacrifices had to be made as a result but I am glad to have truly enjoyed and benefited from this fulfilling journey. This thesis, in many ways, is the culmination of my academic journey, one fraught with challenges but also laden with rewards. It also marks the start of a new chapter of my life where I leave the comfortable and sheltered confines of the university into the “outside world” and my future pursuit of a career in education. I would like to express my heartfelt thanks and gratitude to the following people, without whom this thesis would not have been possible: I am foremost indebted to Associate Professor K. Raguraman who first inspired me in the wonderful field of transport geography from the undergraduate modules I did under him. His endearing self, intellectual guidance, critical comments and helpful suggestions have been central to the completion of this thesis. A special word of thanks to you Ragu, my supervisor, mentor, inspiration and friend. All faculty members at the Department of Geography, NUS who have taught me (hopefully well enough!) during my undergraduate and postgraduate days in the university and enabled me to see the magic behind the discipline that is Geography. -

Singapore Changi Quick Response Center Service and Repair • On-Site Services Compressor Dry Gas Seals Pump Seal Change-Outs and Upgrades

Singapore Changi Quick Response Center Service and Repair • On-Site Services Compressor Dry Gas Seals Pump Seal Change-Outs and Upgrades 1 Experience In Motion Repair Service and Technical Support The Flowserve Singapore Changi Quick Response Working closely with our customers to help improve Center (QRC) is focused on providing customers the reliability and performance of their rotating equip- with uncompromising service and technical ment through quick access to the best seal for the support. application, the Changi QRC is able to ensure the maximum uptime and performance of our customer’s Staffed by highly skilled engineers and technicians key equipment. around the clock, the Changi QRC is available The range of services offered by the Changi QRC to respond to customer requests for support in includes: troubleshooting problems and providing reliable solutions with their rotating equipment seals. • Engineering and manufacturing of mechanical seals and systems, including wet seals, dry gas seals and mixer seals Premier, Value-Added Service • Seal change-outs, upgrades and repairs Combining rotating equipment and seal knowledge, • Installation and commissioning services design experience and manufacturing capability, the • On-site repair and diagnostic services Flowserve Changi QRC consistently sets the industry • Field supervision standard for value added repair and upgrade services • Service maintenance contracts in the region. The proven level of knowledge and experience of the Changi engineers and technicians make it possible to service most types of rotating equipment seals, including seals for pumps, compressors and agitators. Flowserve has documented experience with upgrading all types of mechanical seals and associated equipment, including those originally manufactured by other suppliers. -

List-Of-Bin-Locations-1-1.Pdf

List of publicly accessible locations where E-Bins are deployed* *This is a working list, more locations will be added every week* Name Location Type of Bin Placed Ace The Place CC • 120 Woodlands Ave 1 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Apple • 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-06, MBS • 270 Orchard Rd Battery and Bulb Bin • 78 Airport Blvd, Jewel Airport Ang Mo Kio CC • Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Best Denki • 1 Harbourfront Walk, Vivocity, #2-07 • 3155 Commonwealth Avenue West, The Clementi Mall, #04- 46/47/48/49 • 68 Orchard Road, Plaza Singapura, #3-39 • 2 Jurong East Street 21, IMM, #3-33 • 63 Jurong West Central 3, Jurong Point, #B1-92 • 109 North Bridge Road, Funan, #3-16 3-in-1 Bin • 1 Kim Seng Promenade, Great World City, #07-01 (ICT, Bulb, Battery) • 391A Orchard Road, Ngee Ann City Tower A • 9 Bishan Place, Junction 8 Shopping Centre, #03-02 • 17 Petir Road, Hillion Mall, #B1-65 • 83 Punggol Central, Waterway Point • 311 New Upper Changi Road, Bedok Mall • 80 Marine Parade Road #03 - 29 / 30 Parkway Parade Complex Bugis Junction • 230 Victoria Street 3-in-1 Bin Towers (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Merah CC • 4000 Jalan Bukit Merah 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Panjang CC • 8 Pending Rd 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Bukit Timah Plaza • 1 Jalan Anak Bukit 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, Bulb, Battery) Cash Converters • 135 Jurong Gateway Road • 510 Tampines Central 1 3-in-1 Bin • Lor 4 Toa Payoh, Blk 192, #01-674 (ICT, Bulb, Battery) • Ang Mo Kio Ave 8, Blk 710A, #01-2625 Causeway Point • 1 Woodlands Square 3-in-1 Bin (ICT, -

Download Location

Changi DR Golf Course IS 12 R R I Overseas S A Family Sch P EVERYTHING AT B UA Pasir Ris Wafer N Fabrication Park Pasir Ris G Pk KO K E A S T D R Wild Wild Downtown Wet East D R PASIR RIS D S R 3 A T I P YOUR FINGERTIPS A Tampines Wafer A L S M E IR Fabrication Park RI PASIR RIS P S D IKEA R I 1 N 8 T E A Courts R Pasir Ris S D M Town Pk P S E I White IN The Alps Residences is located at Tampines Avenue 10, Giant LINK X R S E PINE Sands S TAM P R R I along Street 86. With a home near lifestyle destinations D R S A E P PA S SIR R and an effective transport network, everything else IS S DR E 1 V W A becomes closer to you. From recreational activities to G JTC Space@ A N Y A Tampines North ( Y retail therapy, all that you could ever want is simply T P O E ) L moments away. 2 1 2 E E V V A Tampines A S Eco Green Pk RD D E MPINES RETAIL & ENTERTAINMENT TA N N I I P Dunman S T Sec Sch CHANGI E M A M AIRPORT • OUR TAMPINES HUB (U/C) N A I P T T I P A N M E M P I TAMPINES AVE 9 S • TAMPINES MALL N A E T S A I 6 N V ) D United E E AV V Tampines • TAMPINES 1 E World E 9 3 A Sun Plaza Jnr College (SEA) S Pk College P Gongshang Poi Ching E East Spring • CENTURY SQUARE Sch N Pri Sch Sec Sch T I K A MP P TAMPINES AVE 7 IN M ( E • TAMPINES RETAIL PARK S AVE 5 A Tampines Tampines 1 T Bus 8 Interchange Y TAMPINES 0 • DOWNTOWN EAST 1 TAMPINES E Pasir Ris EAST E 6 V Junyuan A V 8 A Sec Sch Sec Sch U/C A T S • SINGAPORE EXPO S Our Tampines Hub S E Century W E S N (U/C) I Tampines N E Square I P Mall Ngee Ann S Tampines N P I M Sec Sch Quarry P E 4 M A AV -

Annual Report

Taking Flight. 24/7. Annual Report 2007/2008 We aim to be the fi rst-choice provider of airline ground services and infl ight solutions by leveraging on our capability to exceed users’ expectations. 1 Key Figures 2 Excellence. 24/7. 4 One with You. 24/7. 6 Connected. 24/7. 10 Strong Financials. 24/7. 12 Chairman’s Statement 18 Board of Directors 22 Key Management 24 Statistical Highlights 25 Subsidiaries & Overseas Investments 26 SATS at a Glance 28 Signifi cant Events 29 Financial Calendar 30 Singapore Operations Review 32 – Ground Handling 36 – Infl ight Catering 40 Overseas Operations Review 41 – Ground Handling 44 – Infl ight Catering 48 Financial Review FY2007-08 57 Corporate Governance 72 Internal Controls Statement 76 Investor Relations 77 Financials 143 Notice of Annual General Meeting 147 Proxy Form IBC Corporate Information Key Figures (for the last fi ve fi nancial years) 2003-04 2005-06 TODAY Revenue Revenue Revenue $868.7m $932.0m $958.0m PATMI PATMI PATMI $188.2m $188.6m $194.9m Total assets Total assets Total assets $1,559m $1,718m $1,850m Ordinary dividend per share Ordinary dividend per share Ordinary dividend per share 8.0¢ 10.0¢ 14.0¢ Presence in Presence in Presence in 14 airports 23 airports 40 airports 07 countries 10 countries 09 countries Number of joint ventures Number of joint ventures Number of joint ventures 12 15 18 1 SATS Annual Report 2007/2008 Key Figures Excellence. 24/7. Well poised to grow beyond Singapore SATS’ pole position as the leading provider of integrated ground handling and infl ight catering services at Singapore Changi Airport, as well as our proven track record of 60 years, have propelled us to make a successful transformation from a pure Singapore play to a formidable force in Asia. -

Public Prosecutor V Low Chuan

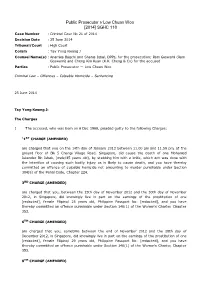

Public Prosecutor v Low Chuan Woo [2014] SGHC 118 Case Number : Criminal Case No 21 of 2014 Decision Date : 25 June 2014 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Tay Yong Kwang J Counsel Name(s) : Anamika Bagchi and Shahla Iqbal, DPPs, for the prosecution; Ram Goswami (Ram Goswami) and Cheng Kim Kuan (K.K. Cheng & Co) for the accused Parties : Public Prosecutor — Low Chuan Woo Criminal Law – Offences – Culpable Homicide – Sentencing 25 June 2014 Tay Yong Kwang J: The Charges 1 The accused, who was born on 6 Dec 1968, pleaded guilty to the following Charges: “1ST CHARGE (AMENDED) are charged that you on the 14th day of January 2013 between 11.00 pm and 11.59 pm, at the ground floor of Blk 5 Changi Village Road, Singapore, did cause the death of one Mohamed Iskandar Bin Ishak, (male/45 years old), by stabbing him with a knife, which act was done with the intention of causing such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, and you have thereby committed an offence of culpable homicide not amounting to murder punishable under Section 304(a) of the Penal Code, Chapter 224. 3RD CHARGE (AMENDED) are charged that you, between the 15th day of November 2012 and the 30th day of November 2012, in Singapore, did knowingly live in part on the earnings of the prostitution of one [redacted], female Filipino/ 25 years old, Philippine Passport No: [redacted], and you have thereby committed an offence punishable under Section 146(1) of the Women's Charter, Chapter 353. 6TH CHARGE (AMENDED) are charged that you, sometime between the end of November 2012 and the 28th day of December 2012, in Singapore, did knowingly live in part on the earnings of the prostitution of one [redacted], female Filipino/ 29 years old, Philippine Passport No: [redacted], and you have thereby committed an offence punishable under Section 146(1) of the Women's Charter, Chapter 353. -

Singapore Changi Airport Dropsonde for Weather

41621Y_Vaisala156 6.4.2001 10:05 Sivu 1 156/2001156/2001 Extensive AWOS System: Singapore Changi Airport 2000 NWS Isaac Cline Meteorology Award: Dropsonde for Weather Reconnaissance Short-Term Weather Predictions in Urban Zones: Urban Forecast Issues and Challenges The 81st AMS Annual Meeting: Precipitation Extremes and Climate Variability 41621Y_Vaisala156 6.4.2001 10:05 Sivu 2 Contents President’s Column 3 Vaisala’s high-quality customer Upper Air Obsevations support aims to offer complete solutions for customers’ AUTOSONDE Service and Maintenance measurement needs. Vaisala Contract for Germany 4 and DWD (the German Dropsonde for Weather Reconnaissance in the USA 6 Meteorological Institute) have signed an AUTOSONDE Service Ballistic Meteo System for the Dutch Army 10 and Maintenance Contract. The service benefits are short GPS Radiosonde Trial at Camborne, UK 12 turnaround times, high data Challenge of Space at CNES 14 availability and extensive service options. Surface Weather Observations World Natural Heritage Site in Japan 16 The First MAWS Shipped to France for CNES 18 Finland’s oldest and most Aviation Weather experienced helicopter operator Copterline Oy started scheduled The Extesive AWOS System to route traffic between Helsinki Singapore Changi Airport 18 and Tallinn in May 2000. Accurate weather data for safe The New Athens International Airport 23 journeys and landings is Fast Helicopter Transportation Linking Two Capitals 24 provided by a Vaisala Aviation Weather Reporter AW11 system, European Gliding Champs 26 serving at both ends of the route. Winter Maintenance on Roads Sound Basis for Road Condition Monitoring in Italy 28 Fog Monitoring Along the River Seine 30 The French Air and Space Academy has awarded its year Additional Features 2000 “Grand Prix” to the SAFIR system development teams of Urban Forecast Issues and Challenges 30 Vaisala and ONERA (the The 81st AMS Annual Meeting: French National Aerospace Precipitation Extremes and Climate Variability 38 Research Agency). -

So, Your Loved One Is Going to Prison…

so, your loved one is going to prison… Not sure what to do or what happens next? In ‘RISE: A Book for Families of First-time Offenders’, we help you discover: RISE ❥ what happens to your loved one in prison, ❥ how to cope with the feelings you may be experiencing, ❥ how your child might be affected by the imprisonment and what you can do to help, ❥ what to expect when your loved one comes home, and ❥ resources you can turn to. Collaboration between: ReinTEGraTinG THroUGH InsPiraTion, SUPPorT, anD EMPOWerMenT ReinTEGraTinG THroUGH InsPiraTion, SUPPorT, anD EMPOWerMenT FOREWORD I recently spoke at the Family Justice Practice Forum: Family Justice 2020 (on 14 July 2017) on the complexity of family justice, stressing that those who face an important issue for the first time in an unfamiliar environment are likely to be very much distressed by the experience. While speaking of this in reference to family disputes brought to court and its implications on spouses and children, this much is also true for the families of first-time offenders. Very often, the silent and oft overlooked victims of incarceration are loved ones who have witnessed the imprisonment of a family member. Faced with a unique set of challenges, guidance and support is necessary if they are to successfully navigate new and unfamiliar terrain. There already exists a wide variety of information and services available for these families. However, if this is not presented in an accessible and digestible manner it can be perceived as information overload, and if that happens it ends up adding to the families’ sense of loss and confusion.