Yahuarraju and Rurec, Cordillera Blanca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cordillera Blanca : Glaciares En La Historia

Bull. Inst. Fr. &tildes andines 36 B. FRANCOU, P. RlBSTElN - 1995, 24 (1): 37-64 THOMPSON, L.G., 1992- Ice core evidence from Peru and China. in :Clirrrnte sir~eA.D.1500.(R. Bradley and P.D. Jones editors) :517-548, London: Routledege. THOMPSON, L.G., MOSLEY-THOMPSON, E. C MORALES ARNAO, B., 1984 - El Niiio Southern Oscillation events recorded in the stratigraphy of the Tropical Quelccaya ice cap, Peru. Science, :50-53. 22 M. THOMPSON,J., L.G., MOSLEY-THOMPSON, E., DAVIS, M., LIN, P.N., YAO,T., DYURGEROV, & DAI, 1993- ”Recent warming” : ice core evidence from tropical ice cores with empllass on Central Asia. Globnl nird Plnrv&?ry Clrnqe, 7 : 145-156. CORDILLERA BLANCA GLACIARES EN LA HISTORIA I I *O Resumen Seminario internacional: La mis vasta cobertura glaciar situada entre los trilpicos aqarece como objeto de estudio AIUSE ESTRUCTURAL, POL“ AGRARIASY SECTOR AGROPECUARIO EN BOUMA, CHILE, ECUADOR Y PERU, rela tivainente tarde, a fines del sigla XIX, sobre todo gracias a Ias expediciones austro alemanas a partir organizado por el CEPES y FAO y realizado en mayo de 1994 en la ciudad de Lima. de los aiios 1930-1940.EI desarrollo del alpinismo y un gran nilmero de catistrofes mortales asociadas a la dinimica de estos glaciares (rotura de lagunas de represa morrénica, avalanchas) atrajeron la Ajuste estructural el papel relativo del sector agrario en el desarrollo del PerídJuvier lgiiifiíí y atención ysuscitaron investigaciones glaciológicas.En 1980,seencuentran entre losmejormonitoreados de losglaciares tropicales,primero, gracias a un programa -

476 the AMERICAN ALPINE JOURNAL Glaciers That Our Access Was Finally Made Through the Mountain Rampart

476 THE AMERICAN ALPINE JOURNAL glaciers that our access was finally made through the mountain rampart. One group operated there and climbed some of the high-grade towers by stylish and demanding routes, while the other group climbed from a hid- den loch, ringed by attractive peaks, north of the valley and intermingled with the mountains visited by the 1971 St. Andrews expedition (A.A.J., 1972. 18: 1, p. 156). At the halfway stage we regrouped for new objec- tives in the side valleys close to Base Camp, while for the final efforts we placed another party by canoe amongst the most easterly of the smooth and sheer pinnacles of the “Land of the Towers,” while another canoe party voyaged east to climb on the islands of Pamiagdluk and Quvernit. Weather conditions were excellent throughout the summer: most climbs were done on windless and sunny days and bivouacs were seldom contem- plated by the parties abseiling down in the night gloom. Two mountains may illustrate the nature of the routes: Angiartarfik (1845 meters or 6053 feet; Grade III), a complex massive peak above Base Camp, was ascended by front-pointing in crampons up 2300 feet of frozen high-angled snow and then descended on the same slope in soft thawing slush: this, the easiest route on the peak, became impracticable by mid-July when the snow melted off to expose a crevassed slope of green ice; Twin Pillars of Pamiagdluk (1373 meters or 4505 feet; Grade V), a welded pair of abrupt pinnacles comprising the highest peak on this island, was climbed in a three-day sortie by traversing on to its steep slabby east wall and following a thin 300-metre line to the summit crest. -

Folleto Inglés (1.995Mb)

Impressive trails Trekking in Áncash Trekking trails in Santa Cruz © J. Vallejo / PROMPERÚ Trekking trails in Áncash Áncash Capital: Huaraz Temperature Max.: 27 ºC Min.: 7 ºC Highest elevation Max.: 3090 meters Three ideal trekking trails: 1. HUAYHUASH MOUNTAIN RANGE RESERVED AREA Circuit: The Huayhuash Mountain Range 2. HUASCARÁN NATIONAL PARK SOUTH AND HUARAZ Circuit: Olleros-Chavín Circuit: Day treks from Huaraz Circuit: Quillcayhuanca-Cójup 3. HUASCARÁN NATIONAL PARK NORTH Circuit: Llanganuco-Santa Cruz Circuit: Los Cedros-Alpamayo HUAYHUASH MOUNTAIN RANGE RESERVED AREA Circuit: Huayhuash Mountain Range (2-12 days) 45 km from Chiquián to Llámac to the start of the trek (1 hr. 45 min. by car). This trail is regarded one of the most spectacular in the world. It is very popular among mountaineering enthusiasts, since six of its many summits exceed 6000 meters in elevation. Mount Yerupajá (6634 meters) is one such example: it is the country’s second highest peak. Several trails which vary in length between 45 and 180 kilometers are available, with hiking times from as few as two days to as many as twelve. The options include: • Circle the mountain range: (Llámac-Pocpa-Queropalca Quishuarcancha-Túpac Amaru-Uramaza-Huayllapa-Pacllón): 180 km (10-12 days). • Llámac-Jahuacocha: 28 km (2-3 days). Most hikers begin in Llámac or Matacancha. Diverse landscapes of singular beauty are clearly visible along the treks: dozens of rivers; a great variety of flora and fauna; turquoise colored lagoons, such as Jahuacocha, Mitucocha, Carhuacocha, and Viconga, and; the spectacular snow caps of Rondoy (5870 m), Jirishanca (6094 m), Siulá (6344 m), and Diablo Mudo (5223 m). -

Rutas Imponentes Rutas De Trekking En Áncash Ruta De Trekking Santa Cruz © J

Rutas imponentes Rutas de trekking en Áncash de Santa Cruz © J. Vallejo / PROMPERÚ trekking Ruta de Rutas de trekking en Áncash Áncash Capital: Huaraz Temperatura Máx.: 27 ºC Mín.: 7 ºC Altitud Máx.: 3090 msnm Tres rutas ideales para la práctica de trekking: 1. ZONA RESERVADA CORDILLERA HUAYHUASH (ZRCH) Circuito: Cordillera Huayhuash 2. PARQUE NACIONAL HUASCARÁN (PNH) SUR Y HUARAZ Circuito: Olleros-Chavín Circuito: Trekkings de 1 día desde Huaraz Circuito: Quillcayhuanca-Cójup 3. PARQUE NACIONAL HUASCARÁN (PNH) NORTE Circuito: Llanganuco-Santa Cruz Circuito: Los Cedros-Alpamayo ZONA RESERVADA CORDILLERA HUAYHUASH (ZRCH) Circuito: Cordillera Huayhuash (2-12 días) A 45 km de Chiquián a Llámac, donde se inicia la caminata (1 h 45 min en auto). Esta ruta es considerada como uno de los 10 circuitos más espectaculares en el mundo para el trekking. Además, es muy popular entre los aficionados al andinismo, pues entre sus múltiples cumbres, seis superan los 6000 m.s.n.m. Tal es el caso del nevado Yerupajá (6634 m.s.n.m.), el segundo más alto del país. Se pueden realizar diversas rutas que demandan entre 2 a 12 días de camino, por lo que la longitud del trekking varía según el tiempo de recorrido, siendo los promedios entre 45 y 180 kilómetros, así tenemos: • Rodear la cordillera (Llámac-Pocpa-Queropalca Quishuarcancha-Túpac Amaru-Uramaza-Huayllapa- Pacllón): 180 km (10-12 días). • Llámac-Jahuacocha: 28 km (2-3 días). La mayoría de caminantes suelen iniciar el recorrido en Llámac o Matacancha. Durante el recorrido es posible apreciar diversos paisajes de singular belleza como los espectaculares nevados: Rondoy (5870 m), Jirishanca (6094 m), Siulá (6344 m), Diablo Mudo (5223 m), entre otros; decenas de ríos; lagunas color turquesa como Jahuacocha, Mitucocha, Carhuacocha y Viconga; una gran diversidad de flora y fauna. -

Carhuascancha : Chavin Trek

PERUVIAN ANDES ADVENTURES OLLEROS : CARHUASCANCHA : CHAVIN TREK 6 days (7 day option and also 5 day option) Grade: Medium Highest Point: 4850m Note: The Chavin Ruins are not open on Mondays, if you are planning a trek with a visit to Chavin, plan the trek dates so you do not finish in Chavin on a Monday Our Olleros Carhuascansha trek is a magical journey into a remote and beautiful unspoilt area of the Cordillera Blanca not known to many other trekking groups. We follow an ancient pre Inca route and are treated to fantastic mountain views, waterfalls many small crystal blue mountain lakes and traditional Andean mountain villages where there are no roads and very little contact with foreign tourists and trekkers. On the return to Huaraz from the finish of the trek we stop first to visit the new and modern museum where we will have an insight into the technologically and culturally advanced Chavin Culture the oldest major culture in Peru existing from around 1000 to 300 BC. Then we go on to the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar which was the administration and religious centre of the Chavín culture,. The site of Chavín de Huántar is an incredible feat of engineering, with most of the construction being built underground in an extensive labyrinth of interconnecting chambers, tunnels, ventilation ducts and water canals. Chavin Peter from the USA: Having done treks in the Cuzco and Abancay region, I have to say that this little Cordilleras Blancas trip was my favourite And the Morales brothers were by far the most professional operators I worked with. -

Trekking Como Actividad Turística Alternativa Para El Desarrollo Local Del Distrito De Olleros, Provincia De Huaraz

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL MAYOR DE SAN MARCOS FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ADMINISTRATIVAS E.A.P. DE ADMINISTRACIÓN DE TURISMO Trekking como actividad turística alternativa para el desarrollo local del Distrito de Olleros, Provincia de Huaraz TESIS Para optar el Título Profesional de Licenciado en Administración de Turismo AUTOR Leydi Elsa Ramos Ledesma ASESOR Fray Masías Cruz Reyes Lima – Perú 2015 DEDICATORIA Con cariño y aprecio a Dios, mis queridos padres y hermanos por su apoyo y paciencia para el logro de este objetivo. 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Este trabajo de tesis realizado es un esfuerzo que involucró el apoyo directo e indirecto de distintas personas; por ello deseo expresar mi agradecimiento a aquellos que me dieron su apoyo incondicional durante el desarrollo del trabajo de investigación. Al profesor Fray Cruz, profesor y guía, por su incansable apoyo en la corrección y asesoramiento de este trabajo de tesis. A mis padres y hermanos quienes estuvieron para brindarme toda su ayuda, a mis compañeros y amigos por su motivación. Asimismo a Carla, Carol, Claudia, Lorena, Sigrid, Verónica, Yulissa y Zully por su ayuda en la corrección y apoyo en el trabajo de campo. A los representantes de SERNANP - Huaraz, el Sr. Clodoaldo Figueroa y el Sr. Edson Ramírez. Asimismo, a representantes de la Asociación de Servicio de Auxiliares de Alta Montaña del Sector Olleros - Chavín, el Sr. Calixto Huerta y el Sr. Jorge Martel por su apoyo en las entrevistas realizadas. A representantes y estudiantes de la Escuela de Turismo de la Universidad Santiago Antúnez de Mayolo de Huaraz por las facilidades brindadas para la obtención de información de libros y tesis de la universidad referente a la actividad estudiada. -

A Survey of Andean Ascents 1961-1970

ML A Survey of Andean Ascents 1961-1970 A Survey of Andean Ascents: 1961~1970 Part I. Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru. EVELIO ECHEVARR~A -,!!.-N the years 1962 and 1963, the American A/pine Journal published “A survey of Andean ascents”. It included climbs dating back to the activity deployed by the Andean In- dians in the early 1400’s to the year 1960 inclusive. This present survey attempts to continue the former by covering all traceable Andean ascents that took place from 1961 to 1970 inclusive. Hopefully the rest of the ascents (in Bolivia, Chile and Argentina) will be published in 1974. The writer feels indebted to several mountaineers who readily pro- vided invaluable help: the editor of this journal, Mr. H. Adams Carter, who suggested and directed this project: Messrs. John Ricker (Canada), Olaf Hartmann (Germany) and Mario Fantin (Italy), who all gave advice on several ranges, particularly in Peru. Besides, the following persons also provided important information that helped to solve a good many problems on the history and geography of Andean peaks: Messrs. D.F.O. Dangar and T.S. Blakeney (Great Britain), Ben Curry (Great Britain-Colombia), Ichiro Yoshizawa (Japan), Hans-Dieter Greul and Christian Jahl (Germany), J. Monroe Thorington, Stanley Shepard and John Peyton (United States) and Christopher Jones (Great Britain- United States). The American Alpine Club, through its secretary, Miss Margot McKee, helped immensely by loaning books and journals. To all these persons I express my gratitude. This survey has been compiled mostly from mountaineering and scientific literature, as well as from correspondence and conversation with mountaineers. -

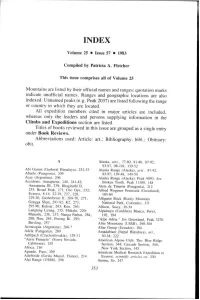

Mountains Are Listed by Their Official Names and Ranges; Quotation Marks Indicate Unofficial Names

INDEX Volume 25 0 Issue 57 0 1983 Compiled by Patricia A. Fletcher This issue comprises al1 of Volume 25 Mountains are listed by their official names and ranges; quotation marks indicate unofficial names. Ranges and geographic locations are also indexed. Unnamed peaks (e.g. Peak 2037) are listed following the range or country in which they are located. All expedition members cited in major articles are included, whereas only the leaders and persons supplying information iti the Climbs and Expeditions section are listed. Titles of books reviewed in this issue are grouped as a single entry under Book Reviews. Abbreviations used: Article: art.; Bibliography: bibl.; Obituary: obit. A Alaska, arts., 77-80, 81-86, 87-92, 93-97, 98-101; 139-52 Abi Gamin (Garbwal Himalaya), 252-53 Alaska Range (Alaska), arts.. 87-92, Abuelo (Patagonia), 209 93-97; 139-48, 149-50 Acay (Argentina), 206 Alaska Range (Alaska): Peak 9050. See Accidents: Annapuma, 240, 241-42; Broken Tooth. Peak 11300, 148 Annapuma III, 239; Bhagirathi II, Aleta de Tiburbn (Patagonia), 212 253; Broad Peak, 271; Cho Oyu, 232; Alfred Wegener Peninsula (Greenland), Everest, 8-14. 22-29, 227, 228, 183-84 229-30; Gasherbrum II, 269-70, 271; Alligator Rock (Rocky Mountain Gongga Shari,, 291-92; K2, 273, National Park, Colorado), 171 295-96; Kuksar, 283; Kun, 265; Allison, Stacy, 30-34 Langtang Lirung, 235; Makalu, 220; Alpamayo (Cordillera Blanca, Peru), Manaslu, 236, 237; Nanga Parbat, 284, 192, 194 288; Nun, 263. Porong Ri, 295; “Alpe Adria.” See Greenland, Peak 3270. Shivling, 257 Altai Mountains (USSR), 298-300 Aconcagua (Argentina), 206-7 Altar Group (Ecuador), 184 Adela (Patagoma), 209 Amadablam (Nepal Himalaya), an., AdrSpach (Czechoslovakia), 129-3 1 30-34; 222 “Aene Pinnacle” (Sierra Nevada, American Alpine Club, The: Blue Ridge California), 155 Section. -

Complete Thesis

Morphology, exhumation, and Holocene erosion rates from a tropical glaciated mountain range: the Cordillera Blanca, Peru by Keith R. Hodson Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences McGill University, Montreal August 2012 A thesis to be submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Science © Keith R. Hodson, 2012 Acknowledgements This project was made possible with the support of many people who helped me along the way. First and foremost, none of the work from the last two years would have ever been realized without the aid of my advisor Dr. Sarah Hall. It is only with her continued support, guidance, and attention that this project has grown to it’s current state of completion. Cosmogenic and thermochronologic analyses were made possible with the aid of Melanie Michalak, Daniel Farber, and Jeremy Hourigan from the University of California, Santa Cruz, Earth and Planetary Sciences department. Undergraduates Phillip Greene, Marc-Antoine Fortin, and Kasparas Spokas were invaluable in the lab and during field work, and I wish them all luck on their future endeavors. Thanks to Marc-Antoine Longpré for help with translation. Big thanks to officemates Tyler Doane, Simon Yang, and David Corozza for the company and continuing support, even now that we are spread across the globe. Thanks to Anne Kosowski, Kristy Thornton and Angela Di Ninno for ensuring a smooth graduate school experience. And lastly: endless thanks to my parents for remaining supportive and encouraging this whole time, even -

Peruvian Andes Adventures Olleros to Chavin Trek 3

PERUVIAN ANDES ADVENTURES OLLEROS TO CHAVIN TREK 3 days Grade: Easy to Medium Highest Point: 4700m Laguna Huamanpinta Note: The Chavin Ruins do not open on Mondays. If you are planning a trek with a visit to Chavin, plan the trek dates so you do not finish in Chavin on a Monday. For 3 days, we follow an ancient, pre-Inca pathway through a remote area of the Cordillera Blanca, a long way from the range’s busier trekking circuits. As we go, we will encounter traditional communities where locals still live as their ancestors did. The trek ends at the enigmatic archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar, the religious and administrative centre of the Chavín culture. This feline-worshipping culture thrived from around 1000 to 300 BC, making it the oldest major culture Peru ever had. Chavín de Huántar is an incredible feat of engineering, with most of the construction being underground in the form of an extensive labyrinth of interconnecting chambers, tunnels, ventilation ducts and water canals. Our trek offers an exciting mix of hiking through beautiful and remote countryside, encounters with the local culture through meeting local people in remote communities, and ancient Andean history. If you are looking for a short, relaxing trek away from the busier circuits, then you are sure to enjoy this cultural trekking itinerary. Testimonials: Olleros to Chavin Trek: Allan Willocks from Australia:“Overall this was an excellent trip. It was great to do a trek where the only people that we saw were the locals going about their daily lives. I am surprised that this isn’t a more well known trek!” Peter from the USA: Having done treks in the Cuzco and Abancay region, I have to say that this little Cordilleras Blancas trip was my favourite And the Morales brothers were by far the most professional operators I worked with. -

5434 Masl Huamashraju, Yanahuacra Or

INTERMEDIATE LEVEL CLIMBS Altitude: 5434 m.a.s.l. Huamashraju, Yanahuacra or RajuColta is a mountain in the Cordillera Blanca in the Andes of Peru, about 5,434 meters (17,828 ft.) high, part of the Huatsan mastiff. Huamashraju lies east of the town of Huaraz, west of Huatsán and northwest of Shacsha and Cashan. It can be seen from most parts of Huaraz. This mountain is a more technical climb and is close to Huaraz, making it a great technical acclimatization climb for those with some experience. We suggest you arrive in Huaraz at least 2 days prior to the start of the trip. This will allow for proper acclimation as Huaraz sits at 10,000’ in elevation. It also allows us to meet up with you to review the days ahead and check to ensure you have proper clothing and gear. Gear is rentable upon request. Day 1: Huaraz – Jancu - Huamashraju Base Camp (4500m) Today we’ll head out of Huaraz around 8:00AM and drive approximately 1 hour to the trailhead in Jancu village. From here we’ll hike up to Huamashraju Base Camp, approx. 3-4 hours. From here we have beautiful lake and mountain views. We’ll prepare lunch either in route or at camp depending on group pacing. Dinner and sleep at camp. Day 2: Huamashraju Base Camp - Summit - Base Camp After a quick breakfast, we’ll break camp at about 2:00AM and begin the steady climb through the moraine until we reach the glaciers edge. Once geared up, we’ll start the climb to the ridge, and then traverse below the summit to the wall. -

Flora and Vegetation of the Huascarán National Park, Ancash, Peru: With

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1988 Flora and vegetation of the Huascarán National Park, Ancash, Peru: with preliminary taxonomic studies for a manual of the flora David Nelson Smith Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, David Nelson, "Flora and vegetation of the Huascarán National Park, Ancash, Peru: with preliminary taxonomic studies for a manual of the flora " (1988). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 8891. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/8891 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.