MATH 310 ¸Selftest¹ Transformation Geometry SOLUTIONS & COMMENTS F05 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transformation Geometry — Math 331

Transformation Geometry — Math 331 March 8, 2004 Conjugation of Isometries Definition. If f and g are invertible affine transformations of Rn, the conjugate of f by g is the transformation g ◦ f ◦ g−1. When the context is clear, one sometimes abbreviates notation for conjugation by writing g · f = g ◦ f ◦ g−1 . One views this as g “acting on” f. That is, an affine transformation of Rn not only describes a motion of Rn but also a motion on the set of affine transformations of Rn: the action of the set of affine transformations on itself by conjugation. Theorem 1. If f(x) = Ux + v is an affine transformation of Rn and τ(x) = x + a is translation by the vector a, then f · τ is translation by the vector Ua. Proof. f −1(x) = U −1x − U −1v, and, therefore y = τ ◦ f −1(x) = U −1x − U −1v + a. Then (f · τ)(x) = Uy + v = x + Ua. Warning. Although when a translation is conjugated by an arbitrary affine transformation, the result is a translation, it is not true that the result of conjugating an isometry by an affine transformation is always an isometry. For example, if f is the simple linear transformation (x, y) 7→ (2x, y) of R2 and ρ is rotation through the angle π/2 about the origin, i.e., (x, y) 7→ (−y, x), then f · ρ is the linear map (x, y) 7→ (−2y, x/2), which is not an isometry. On the other hand, it is clear that the result of conjugating an isometry by an isometry is an isometry. -

II.3 : Measurement Axioms

I I.3 : Measurement axioms A large — probably dominant — part of elementary Euclidean geometry deals with questions about linear and angular measurements , so it is clear that we must discuss the basic properties of these concepts . Linear measurement In elementary geometry courses , linear measurement is often viewed using the lengths of line segments . We shall view it somewhat differently as giving the (shortest) distance 2 3 between two points . Not surprisingly , in RRR and RRR we define this distance by the usual Pythagorean formula already given in Section I.1. In the synthetic approach , one may view distance as a primitive concept given formally by a function d ; given two points X, Y in the plane or space , the distance d (X, Y) is assumed to be a nonnegative real number , and we further assume that distances have the following standard properties : Axiom D – 1 : The distance d (X, Y) is equal to zero if and only if X = Y. Axiom D – 2 : For all X and Y we have d (X, Y) = d (Y, X). Obviously it is also necessary to have some relationships between an abstract notion of distance and the other undefined concepts introduced thus far ; namely , lines and planes . Intuitively we expect a geometrical line to behave just like the real number line , and the following axiom formulated by G. D. Birkhoff (1884 – 1944) makes this idea precise : Axiom D – 3 ( Ruler Postulate ) : If L is an arbitrary line , then there is a 1 – 1 correspondence between the points of L and the real numbers RRR such that if the points X and Y on L correspond to the real numbers x and y respectively , then we have d (X, Y) = |x – y |. -

Augmented Reality Mobile Learning System: Study to Improve Psts’ Understanding of Mathematical Development

Short Paper—Augmented Reality Mobile Learning System: Study Study to Improve PSTs’… Augmented Reality Mobile Learning System: Study to Improve PSTs’ Understanding of Mathematical Development https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i09.12909 Mohammad Faizal Amir(), Novia Ariyanti, Najih Anwar Universitas Muhammadiyah Sidoarjo, Sidoarjo, Indonesia [email protected] Erik Valentino STKIP Bina Insan Mandiri Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia Dian Septi Nur Afifah STKIP PGRI Tulungagung, Tulungagung, Indonesia Abstract—Augmented Reality research in mobile learning systems so far have not especially to improve Preservice Students Teachers' (PSTs) geometry understanding in mathematical development. Studies conducted in this study ba- sically use a case study. This research aims to develop a mobile augmented reality system for PSTs learning so that it can be used to improve PSTs understanding of mathematics development includes doing, image-making, an image having, property noticing, formalizing, observing, structuring and inventing. In this de- velopment, PSTs can understand the understanding of the geometry transfor- mation is a translation, reflection, rotation, and dilatation. Keywords—Mobile systems, augmented reality, understanding mathematics, geometry transformation. 1 Introduction In PISA 2015 mathematics assessed as minor domains, providing the opportunity to make comparisons of student performance over time. The results of preliminary field studies, mathematical understanding of geometry Preservice Student Teachers (PSTs) 20 of 36 in Universitas Muhammadiyah Sidoarjo have difficulty in solving mathemat- ical understanding of geometry. The development of learners by understanding participants [1] includes doing, im- age-making, an image having, property noticing, formalizing, observing, structuring, and inventing, linking concepts, ideas, facts, or mathematics procedures. Results of re- search by [2], [6] shows the importance of understanding the development problems of geometry PSTs that many of the teachers or prospective elementary school teachers do iJIM ‒ Vol. -

M2.1 - Transformation Geometry

RHODES UNIVERSITY Grahamstown 6140, South Africa Lecture Notes CCR M2.1 - Transformation Geometry Claudiu C. Remsing DEPT. of MATHEMATICS (Pure and Applied) 2006 ‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’ – that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. John Keats Imagination is more important than knowledge. Albert Einstein Do not just pay attention to the words; Instead pay attention to meaning behind the words. But, do not just pay attention to meanings behind the words; Instead pay attention to your deep experience of those meanings. Tenzin Gyatso, The 14th Dalai Lama Where there is matter, there is geometry. Johannes Kepler Geometry is the art of good reasoning from poorly drawn figures. Anonymous What is a geometry ? The question [...] is metamathematical rather than mathematical, and consequently mathematicians of unquestioned competence may (and, indeed, do) differ in the answer they give to it. Even among those mathematicians called geometers there is no generally accepted definition of the term. It has been observed that the abstract, postulational method that has permeated nearly all parts of modern mathematics makes it difficult, if not meaningless, to mark with precision the boundary of that mathematical domain which should be called geometry. To some, geometry is not so much a subject as it is a point of view – a way of loking at a subject – so that geometry is the mathematics that a geometer does ! To others, geometry is a language that provides a very useful and suggestive means of discussing almost every part of mathematics (just as, in former days, French was the language of diplomacy); and there are, doubtless, some mathematicians who find such a query without any real significance and who, consequently, will disdain to vouchsafe any an- swer at all to it. -

Learners Engaging with Transformation Geometry

South African Journal of Education Copyright © 2012 EASA Vol 32:26-39 Learners engaging with transformation geometry Sarah Bansilal and Jayaluxmi Naidoo Department of Mathematics, University of KwaZulu-Natal [email protected] This article reports on a qualitative, interpretivist study that focused on the use of visualisation and analytic strategies by Grade 12 learners when working with problems based on transformation geometry. The research was conducted with 40 learners from a Grade 12 class at one high school in the north Durban area of Kwazulu-Natal. Participants completed a written task and a smaller sample of the participants engaged in investigative semi-structured interviews with the resear- chers. The framework for the study was based on transformations of semiotic representations as well as the visualiser/analyser model. The findings revealed that most learners performed treatments in the analytic mode when responding to the tasks, and showed limited movement across the two modes which are essential for a deepening of understanding. The study identified one learner, however, who was able to move flexibly between the modes and who displayed a deep understanding of the concepts. The article concludes by recommending that opportunities need to be created for learners to engage in transformation geometry activities which em- phasise conversion. Keywords: analysis; conversions; transformation geometry; transformations; treatments; visualisation Introduction Within the current (2011) South African curriculum, school mathematics incorporates trans- formation geometry, which was introduced in the Further Education and Training (FET) band in 2006. This strand allows learners to make connections across other geometries within the space, shape and measurement learning outcome, as well as with algebra and trigonometry. -

Basic Transformation Geometry

Basic Transformation Geometry For transformation geometry there are two basic types: rigid transformations and non-rigid transformations. This page will deal with three rigid transformations known as translations, reflections and rotations. The Vocabulary of Transformation Geometry In short, a transformation is a copy of a geometric figure, where the copy holds certain properties. Think of when you copy/paste a picture on your computer. The original figure is called the pre-image; the new (copied) picture is called theimage of the transformation. A rigid transformation is one in which the pre-image and the image both have the exact same size and shape. Translations - Each Point is Moved the Same Way The most basic transformation is the translation. The formal definition of a translation is "every point of the pre-image is moved the same distance in the same direction to form the image." Take a look at the picture below for some clarification. Each translation follows a rule. In this case, the rule is "5 to the right and 3 up." You can also translate a pre-image to the left, down, or any combination of two of the four directions. More advanced transformation geometry is done on the coordinate plane. The transformation for this example would be T(x, y) = (x+5, y+3). Reflections - Like Looking in a Mirror A reflection is a "flip" of an object over a line. Let's look at two very common reflections: a horizontal reflection and a vertical reflection. Notice the colored vertices for each of the triangles. The line of reflection is equidistant from both red points, blue points, and green points. -

Transformation Geometry 1.Pub

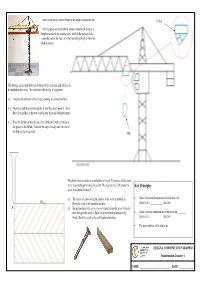

Tower cranes are a common fixture at any major construction site. Trolley The 3D graphic on the left shows a tower crane which contains a long horizontal jib (or working arm), which is the portion of the crane that carries the load. A trolley runs along the jib to move the load in and out. A The drawing on the right shows an elevation of the crane and skip which is to be attached to the trolley. The elevation of the trolley is incomplete. (a) Complete the elevation of the trolley, showing all construction lines. (b) The trolley and skip move along the jib until they reach point A. Show the trolley and skip in the new position after this horizontal movement. (c) When the trolley reaches the end of the jib the skip must be lowered to the ground to be refilled. Translate the skip vertically until the base of the skip reaches the ground. Skip The photo shows a wood screw and a piece of wood. Two pieces of this wood are to be jointed together using the screw. The diagram over (left) shows the Key Principles screw in its initial position A. (a) The screw is to move along the surface of the wood to position A . • Under a horizontal translation all points move the _______ A1 1 Show the screw in the translated position. distance in a ____________ direction A (b) Having positioned the screw, it is to be inserted into the wood vertically until the top of the screw is flush (level) with the top surface of the • Under a vertical translation all points move the ________ wood. -

Geometric Transformations in Middle School Mathematics Textbooks

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Geometric Transformations in Middle School Mathematics Textbooks Barbara Zorin University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Scholar Commons Citation Zorin, Barbara, "Geometric Transformations in Middle School Mathematics Textbooks" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3421 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geometric Transformations in Middle School Mathematics Textbooks by Barbara Zorin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Secondary Education College of Education University of South Florida Major Professor: Denisse R. Thompson, Ph.D. Richard Austin, Ph.D. Catherine A. Beneteau, Ph.D. Helen Gerretson, Ph.D. Gladis Kersaint, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 10, 2011 Keywords: Geometry, Transformations, Middle School, Mathematics Textbooks, Content Analysis Copyright © 2011, Barbara Zorin 1 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my father, Arthur Robert, who provided me with love and support, and who taught me, from a very early age, that I could accomplish anything that I put my mind to. To my son, Rick, for always believing that I was the smartest person he had ever met and showing me that he knew that I would complete this endeavor. -

Relativity Without Tears

Relativity without tears Z. K. Silagadze Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics and Novosibirsk State University, 630 090, Novosibirsk, Russia Special relativity is no longer a new revolutionary theory but a firmly established cornerstone of modern physics. The teaching of special relativ- ity, however, still follows its presentation as it unfolded historically, trying to convince the audience of this teaching that Newtonian physics is natural but incorrect and special relativity is its paradoxical but correct amend- ment. I argue in this article in favor of logical instead of historical trend in teaching of relativity and that special relativity is neither paradoxical nor correct (in the absolute sense of the nineteenth century) but the most nat- ural and expected description of the real space-time around us valid for all practical purposes. This last circumstance constitutes a profound mystery of modern physics better known as the cosmological constant problem. PACS numbers: 03.30.+p Preface “To the few who love me and whom I love – to those who feel rather than to those who think – to the dreamers and those who put faith in dreams as in the only realities – I offer this Book of Truths, not in its character of Truth-Teller, but for the Beauty that abounds in its Truth; constituting it true. To these I present the composition as an Art-Product alone; let us say arXiv:0708.0929v2 [physics.ed-ph] 19 Dec 2007 as a Romance; or, if I be not urging too lofty a claim, as a Poem. What I here propound is true: – therefore it cannot die: – or if by any means it be now trodden down so that it die, it will rise again ”to the Life Everlasting.” Nevertheless, it is a poem only that I wish this work to be judged after I am dead” [1]. -

Transformation Geometry

Geometry Module 2 Transformations Grades 8 and 9 Teacher document Malati staff involved in developing these materials: Kate Bennie Zonia Jooste Dumisani Mdlalose Rolene Liebenberg Piet Human Sarie Smit We acknowledge the assistance of Zain Davis, Shaheeda Jaffer, Mthunzi Nxawe and Raymond Smith in shaping our perspectives. COPYRIGHT All the materials developed by MALATI are in the public domain. They may be freely used and adapted, with acknowledgement to MALATI and the Open Society Foundation for South Africa. December 1999 Malati Geometry: The Transformation Approach A Common Approach to the Study of Plane Geometry: This problem is commonly used in geometry in the senior phase. Find the value of each of the angles p and t. Give reasons for your answers B 42q E 37q A p t C D The mathematical figure in this problem is presented as being static. In order to solve the problem, learners are required to recognise the pairs of corresponding and alternate angles (this is usually done by recognising the “F” and the “Z” in the diagram. ‘Proofs’ in two column format are acceptable. The function of proof in such a case is verification or systematisation (Bell, 1976). Transformation Geometry in the School Curriculum: Traditionally isometric transformations have formed part of the geometry curriculum in South Africa: x In the study of tessellations (although the transformation aspect is seldom made explicit). x As a separate topic in Grade 9, sometimes linked to co-ordinate geometry. Much of this work on transformations has, however, been restricted to the perceptual level, that is, pupils have been given opportunities to physically manipulate figures using cut-outs, paper folding, geoboards, tracings, etc. -

Snapshots from Transformation Geometry

Snapshots from Transformation Geometry Shailesh Shirali Community Mathematics Centre, Sahyadri School & Rishi Valley School (KFI) 29 November 2013, IMSc, Chennai SAS (CoMaC) Snapshots from Transformation Geometry Nov 2013 1 / 44 What is geometry? There are many different ways of defining ‘geometry’ but one of them is: Geometry is the study of shapes, and how their properties are affected by given groups of transformations: which properties are left unaltered, and which ones undergo a change. This view of geometry is due to the mathematician Felix Klein (1849–1925). SAS (CoMaC) Snapshots from Transformation Geometry Nov 2013 2 / 44 What is a ‘Geometric Transformation’? A transformation of the plane is a function defined on the plane, moving points around according to a definite law. Matters of interest: Is the function ‘well behaved’? Is it smooth? Does it preserve length? Angles? Orientation? Area? In today’s talk we shall see how the use of transformations can give rise to elegant proofs of some geometrical propositions. SAS (CoMaC) Snapshots from Transformation Geometry Nov 2013 3 / 44 Affine maps Let f be a bijection of the plane. We say that f is affine if it preserves the property of collinearity. Let the images of points A, B, C,... under f be A′, B′, C ′,.... Let the images of lines l, m under f be l ′, m′. Then: SAS (CoMaC) Snapshots from Transformation Geometry Nov 2013 4 / 44 Affine maps Let f be a bijection of the plane. We say that f is affine if it preserves the property of collinearity. Let the images of points A, B, C,.. -

16.Transformation Geometry (SC)

16. TRANSFORMATION GEOMETRY TRANSFORMATIONS In navigation and other real-life situations, we use the A geometric transformation involves the movement four Cardinal points to describe direction, but our of an object from one position to another on a plane. study of transformations involves mainly movements The movement is accompanied by a change in on the Cartesian Plane and it is therefore convenient position, orientation, shape or even size. Some to refer to these four directions as follows: examples of transformations are translation, reflection, rotation, enlargement, one-way stretch, North (parallel to the �-axis in a positive direction) two-way-stretch and shear. South (parallel to the �-axis in a negative direction) East (parallel to the �-axis in a positive direction) In our study of transformations, we will be concerned West (parallel to the �-axis in a negative direction) mainly with movement of basic shapes (plane figures) from one position to another (image). If there We can also use conventional units to describe is no change in size or shape, then the transformation distance such as metres and centimetres. However, on is called an isometric transformation. If the size of the Cartesian Plane we measure distance using the object changes then the transformation is called a horizontal and vertical scales on a graph. size transformation. Each transformation has a unique set of characteristics or rules that define the Note that translation is used to describe any movement. movement in a straight line. These include horizontal and vertical and diagonal movements. Translation Translation on the Cartesian Plane A translation is a movement, along a straight line, in a fixed direction without any turning.