Domestic Workers‟ Social Networks and the Formation of Political Subjectivities: a Socio-Spatial Perspective”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

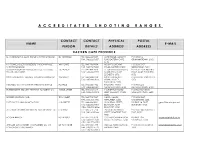

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Draft Air Quality Management Plan

BOJANALA PLATINUM DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY DRAFT AIR QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN May 2011 DRAFT 1 REPORT AUTHORS Nokulunga Ngcukana - Gondwana Environmental Solutions (Pty) Ltd Nicola Walton - Gondwana Environmental Solutions (Pty) Ltd Loren Webster - Gondwana Environmental Solutions (Pty) Ltd Roelof Burger - Climatology Research Group, Wits University Prof. Stuart Piketh - Climatology Research Group, Wits University Hazel Bomba - Gondwana Environmental Solutions (Pty) Ltd 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION The National Environmental Management: Air Quality Act 39 of 2004 (AQA) requires Municipalities to introduce Air Quality Management Plans (AQMP) that set out what will be done to achieve the prescribed air quality standards. Municipalities are required to include an AQMP as part of its Integrated Development Plan. The AQA makes provision for the setting of ambient air quality standards and emission limits on National level, which provides a means evaluating air quality. Due to the implementation of the AQA, the philosophy of managing air quality in South Africa moved from a point source base approach to a more holistic approach based on the effects on the receiving environment (human, plant, animal and structure). The philosophy is based on pro-active planning (air quality management plans for all municipal areas), licensing of certain industrial processes (listed processes), and identifying priority areas where air quality does not meet the air quality standards for certain air pollutants (Engelbrecht, 2009). Air quality management is primarily the minimisation, management and prevention of air pollution, which aims to improve areas with poor air quality and maintain good air quality throughout. In light of this legal requirement, the Bojanala Platinum district municipality (BPDM) developed this AQMP. -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

Recueil Des Colis Postaux En Ligne SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE

Recueil des colis postaux en ligne ZA - South Africa SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE LIMITED ZAA Service de base RESDES Informations sur la réception des Oui V 1.1 dépêches (réponse à un message 1 Limite de poids maximale PREDES) (poste de destination) 1.1 Colis de surface (kg) 30 5.1.5 Prêt à commencer à transmettre des Oui données aux partenaires qui le veulent 1.2 Colis-avion (kg) 30 5.1.6 Autres données transmis 2 Dimensions maximales admises PRECON Préavis d'expédition d'un envoi Oui 2.1 Colis de surface international (poste d'origine) 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non RESCON Réponse à un message PRECON Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus (poste de destination) grand pourtour) CARDIT Documents de transport international Oui 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non pour le transporteur (poste d'origine) (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus RESDIT Réponse à un message CARDIT (poste Oui grand pourtour) de destination) 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui 6 Distribution à domicile (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus grand pourtour) 6.1 Première tentative de distribution Oui 2.2 Colis-avion effectuée à l'adresse physique du destinataire 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non 6.2 En cas d'échec, un avis de passage est Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus laissé au destinataire grand pourtour) 6.3 Destinataire peut payer les taxes ou Non 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non droits dus et prendre physiquement (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus livraison de l'envoi grand pourtour) 6.4 Il y a des restrictions gouvernementales 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui ou légales vous limitent dans la (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus prestation du service de livraison à grand pourtour) domicile. -

North West Bapong Bapong R556 Main Road Kalapeng

PRACTICE PROVINCE PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL ADDRESS PHARMACY NAME CONTACT NUMBER NUMBER NORTH WEST BAPONG BAPONG R556 MAIN ROAD KALAPENG BAPONG (012) 2566447 498599 PHARMACY NORTH WEST BLOEMHOF BLOEMHOF 53 PRINCE STREET BLOEMHOF APTEEK (053) 4331009 6012671 NORTH WEST BOITEKONG RUSTENBURG TLOU STREET IBIZA PHARMACY (014) 5934208 460311 NORTH WEST BOITEKONG RUSTENBURG CORNER TLOU AND VC PHARMACY BOITEKONG (014) 5934208 697532 MPOFU STREET NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS MACLEAN STREET ACACIA PHARMACY (012) 2524344 298840 NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS 16 KERK STREET ALFA PHARMACY - BRITS (012) 2525763 6030726 NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS HENDRIK VERWOERD BRITS MALL PHARMACY (012) 2502837 393762 DRIVE NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS PIENAAR STREET CLICKS PHARMACY BRITS (012) 2522673 300047 NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS CORNER HENDRIK CLICKS PHARMACY BRITS (012) 2500458 393452 VERWOERD DRIVE AND MALL NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS MAPLE8 CHURCH RIDGE STREET ROAD DISA-MED PHARMACY BRITS (012) 2928029 6077765 NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS 20 DE WITS AVENUE KRISHNA MEDI PHARMACY (012) 2522219 115967 NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS VAN VELDEN AVENUE LE ROUX PHARMACY (012) 2524555 6013139 NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS CORNER PROVINCIAL ROAD MEDIRITE PHARMACY BRITS (012) 2502372 396869 AND MAPLE AVENUE MALL NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS DE WITTS LAAN NEL 2 PHARMACY (012) 2523748 6083455 GEMS SB NETWORK PHARMACY – NORTH WEST Page 1 of 9 PRACTICE PROVINCE PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL ADDRESS PHARMACY NAME CONTACT NUMBER NUMBER NORTH WEST BRITS BRITS CORNER CAREL DE WET NEL 3 PHARMACY (012) 2523014 -

Social and Labour Plan November 2009

NOVEMBER 2 SOCIAL AND LABOUR PLAN NOVEMBER 2009 -----------------------------------------Open page for editorial purposes----------------------- - - ii ASPECTS OF THE SCORECARD FOR THE BROAD-BASED SOCIO-ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT CHARTER FOR THE SOUTH AFRICAN MINING INDUSTRY DESCRIPTION 5-YEAR TARGET REGULATION SECTION Human Resource Development Has the company offered every employee Yes No 46 (b) (i) 2 the opportunity to be functionally literate and numerate by the year 2005 and are employees being trained? 9 Has the company implemented career paths Yes No 46 (b) (ii) 5 for HDSA employees including skills development plans? 9 Has the company developed systems Yes No 46 (b) (iii) 6 through which empowerment Companys can be mentored? 9 Employment Equity Has the company published its Yes No 46 (b) (v) 8 employment equity plan and reported on its annual progress in meeting that plan? 9 Has the company established a plan to Yes No 46 (b) (v) 10 achieve a target for HDSA participation in management of 40% within five years and is implementing the plan? 9 Has the company identified a talent pool Yes No 46 (b) (i) 2 and is it fast-tracking it? 9 Has the company established a plan to Yes No 46 (b) (v) 9 achieve the target for women’s participation in mining of 10% within the five years and 9 is implementing the plan? Migrant Labour Has the company subscribed to Yes No 46 (a) 1 government and industry agreements to ensure non-discrimination against foreign 9 migrant labour? Mine Community and Rural Development Has the company co-operated in the Yes -

North West Proposed Main Seat / Sub District Within the Proposed

# # !C # # ### !C^# !.!C# # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # #!C# # # # !C# ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # !C #!C# # # # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C# ## # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # #!C # # #!C # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## ## # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ## # # # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # # !C # #!C # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ### !C # # # # !C !C# # ## # # # ## !C !C #!. # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# # # # ## # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### #^ # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # ^ !C# # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # # !C ## !C## # # # # ## # !C # ## !C# ## # # ## # !C # # ^ # !C ## # # # !C# ^# # # !C # # !C ## !C ### # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # !C## ## # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # !C # # # # # !C ^ # # ## # # # # !. # # # # # # !C # !C# ### -

*Maths&Scienceteacherfet

PAGE 22 RUSTENBURG HERALD 14 JANUARY 2011 HARMONY CHRISTIAN SCHOOL VACANCIES * Maths & Science Teacher FET *Accounting & Economics Teacher FET * Boarding Master We are still open for admission for learners for 2011 Please send a detailed CV and certified copies of your TEACHER VACANCIES qualifications to address: AT The Principal ZINNIAVILLE SECONDARY SCHOOL P.O. Box 3360 SGB POST Rustenburg, 0300 The following vacancies listed below are available. Suitable candidates should apply for them and list E-mail: their preference. [email protected] Fax: 014 597 5926 Post 1: Intermediate Phase -Mathematics School No: 014 597 5925/7 Post 2: GET& FET - Afrikaans & English Applications are invited for the above mentioned posts. Qualified Educators are requested to submit their CV’s, including their SACE Registration Certificate and copies of relevant qualifications. Kindly submit your CV’s to: The Principal: PO Box 50365 Zinniaville 0302 OR Fax at (014) 538 1282 OR e-mail to: [email protected] Closing date: 18 January 2011 NGWEDI (MOGWASE) SUBSTATION & ASSOCIATED 2X400KV TRANSMISSION POWER LINES TURN-INS PROJECT (Proposed Eskom Transmission Project DEA Ref. No. 12/12/20/1566) Proposed construction of Ngwedi substation and 2X400kV Voorgestelde konstruksie van Ngwedi Substasie en transmission power lines near Sun City Resort, North West 2X400kV Transmissie kraglyne naby Sun City Resort, Province. North West Provinsie. DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT KONSEP OMGEWINGSIMPAKVERSLAG AVAILABLE FOR REVIEW BESKIKBAAR VIR HERSIENING A Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) has been ‘n Konsep Omgewingsimpakverslag is deur Margen prepared by Margen Industrial Services and will be industrial Services voorberei en sal op 11 Januarie 2011 available for public review on 11 January 2011. -

Designated Service Providers

carecross 2016_Layout 1 2016/07/25 3:48 PM Page 1 DESIGNATED SERVICE PROVIDERS PLATCAP OPTION ONLY carecross 2016_Layout 1 2016/07/25 3:48 PM Page 2 Platinum Health Contact Details Postal address: Private Bag X82081, Rustenburg, 0300 Administration: RPM Hospital, Bleskop, Rustenburg Website: www.platinumhealth.co.za Platinum Health Client Liaison Contact Details Rustenburg Region Northam Tel: 014 591 6600 or 080 000 6942 Client Liaison Supervisor: 081 037 2977 Fax: 014 592 2252 Client Liaison Officer contact number: 083 719 1040 Client Liaison Supervisor: 083 791 1345 [email protected] Client Liaison Officers contact numbers: 083 842 0195 / 060 577 2303 / 060 571 6895 [email protected] Eastern Limb Client Liaison Supervisor: 083 414 6573 Thabazimbi Region Client Liaison Officers contact number: 083 455 7138 & 060 571 0870 (Union, Amandelbult and Thabazimbi) [email protected] Client Liaison Supervisor: 081 037 2977 Client Liaison Officer contact number: 083 795 5981 Eastern Limb Office [email protected] Client Liaison Supervisor: 015 290 2888 Modikwa office Tel: 013 230 2040 Platinum Health Case Management Contact Details Tel: 014 591 6600 or 080 000 6942 After-hours emergencies: 082 800 8727 Fax: 086 247 9497 / 086 233 2406 Email: [email protected] (specialist authorisation) [email protected] (hospital pre-authorisation and authorisation) Platinum Health Contact Guide for Carecross Designated Service Providers Platcap Option only carecross 2016_Layout -

Human Rights Week 2006 Report

INDEX Section 1 Background 3 Section 2 Human Rights Week planning 4 Section 3 Key findings: Economic and Social Rights 9 Section 4 Launch of Human Rights Day and Puisano 16 Section 5 Media coverage 17 Section 6 Finding and recommendations 18 2 SECTION 1 Background The South African Human Rights Commission (Commission) is the national institution established by section 184 of the Constitution of South Africa Act 108 of 1996, and the South African Human Rights Commission Act 54 of 1994 to entrench constitutional democracy and human rights. The constitutional mandate of the Commission is to: Promote human rights through education and training and raising public awareness Protect human rights through addressing human rights violations and seeking appropriate redress Monitoring and assessing the observance of human rights, particularly economic and social rights The Commission's two focal areas, informed by the strategic objectives, namely the realisation of equality and eradication of poverty, influenced the strong rural community thrust of the 2006 Human Rights Week (HRW) and informed the outreach work done with communities. The Commission celebrates Human Rights Week annually and uses this occasion to: Raise human rights awareness Fast-track the delivery of socio-economic rights amongst communities Monitor government's provision of access to economic and social rights Increase the visibility of the Commission through outreach programmes and the media Investigate human rights violations and seek effective redress. Each year the Commission identifies a particular province as a focus of activities for Human Rights Week. However, the Provincial Offices of the Commission are encouraged to implement separate programmes on a smaller scale. -

Abattoir List 2018 13Feb2018.Xlsx

Contact number for Category Province Abattoir Name Registration Number Town Physical address Provincial Veterinary Species Status (HT/LT/Rural) Services Eastern Cape Aalwynhoek Abattoir 6/67 HT Uitenhage Aalwynhoek, Amanzi, Uitenhage 043 665 4200 Cattle Active Eastern Cape Aalwynhoek Abattoir 6/67 HT Uitenhage Aalwynhoek, Amanzi, Uitenhage 043 665 4200 Sheep Active Eastern Cape Aalwynhoek Abattoir 6/67 HT Uitenhage Aalwynhoek, Amanzi, Uitenhage 043 665 4200 Pigs Active Eastern Cape Aandrus Abattoir 6/36 RT Maclear Aandrus farm, Ugie 043 665 4200 Pigs Active Eastern Cape Adelaide Abattoir 6/2 LT Adelaide No 2 Bon Accord Street, Adelaide, 5760 043 665 4200 Cattle Active Eastern Cape Adelaide Abattoir 6/2 LT Adelaide No 2 Bon Accord Street, Adelaide, 5760 043 665 4200 Sheep Active Eastern Cape Adelaide Abattoir 6/2 LT Adelaide No 2 Bon Accord Street, Adelaide, 5760 043 665 4200 Pigs Active Eastern Cape Aliwal Abattoir 6/5 LT Aliwal North 81 Robinson Road; Aliwal North; 9750 043 665 4200 Cattle Active Eastern Cape Aliwal Abattoir 6/5 LT Aliwal North 81 Robinson Road; Aliwal North; 9750 043 665 4200 Sheep Active Eastern Cape Aliwal Abattoir 6/5 LT Aliwal North 81 Robinson Road; Aliwal North; 9750 043 665 4200 Pigs Active Eastern Cape Anca Poutry Abattoir 6/4P HT Stutterheim Red Crest Farms, 1 Erica Street, Stutterheim, 4930043 665 4200 Poultry Active Eastern Cape Andrews Abattoir 6/75 HT Elliot Ecawa Farm, Elliot, 5460 043 665 4200 Cattle Active Eastern Cape Andrews Abattoir 6/75 HT Elliot Ecawa Farm, Elliot, 5460 043 665 4200 Sheep Active -

CONTRACT DATA Appointment of a Panel of Installers Or

CONTRACT DATA A contract between SENTECH, Sender Technology Park, Radiokop, Octave Road, Honeydew, and ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ for the Appointment of a panel of Installers or Installation Companies for the installation of Domestic Digital Terrestrial Television (DTT) STB’s, Direct to Home (DTH) STBs and Integrated Digital Television Receive System in the North West Province for a period of 3 years Tender Number: SENT/009/2021-22 Tender Ref: SENT/009/2021-22 Page 1 of 34 Contents Part C1: Agreements and contract data Form of Offer and Acceptance Contract Data provided by the Sentech Contract Data provided by the Supplier Part C2: Pricing Data Part C3: Scope of Work Conditions of Contract (available separately) Tender Ref: SENT/009/2021-22 Page 2 of 34 PART C1: AGREEMENTS AND CONTRACT DATA – Form of Offer and Acceptance Offer The Purchaser, identified in the acceptance signature block, has solicited offers to enter into a contract for the installation of DTT/DTH STB Receive system in the Northern Cape. The Bidder, identified in the offer signature block, has examined the documents listed in the Tender Data and addenda thereto as listed in the Bid schedules, and by submitting this offer has accepted the conditions of the Bid. By the representative of the Bidder, deemed to be duly authorized, signing this part of this form of offer and acceptance, the Bidder offers to perform all of the obligations and liabilities of the Bidder under the Contract including compliance with all its’ terms and conditions according to their true intent and meaning for an amount to be determined in accordance with the conditions of contract identified in the Contract Data.