The Trades Hall Part of Our History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Program

Conference Program Tuesday 15 October Welcome Drinks and pre-registration 6 - 8pm Johnny’s Green Room, above King & Godfree, 293-297 Lygon Street Wednesday 16 October Deakin Downtown - Tower 2, Level 12/727 Collins St, Melbourne Time Presentation Title Speaker Format 8.00 Registration 8.45 Conference opening and house keeping Interpretation Australia 8.50 Welcome to Country Uncle Dave Wandin Wurundjeri Land Council 9.00 Host venue welcome Dr Steven Cooke Deakin University 9.10 Mother Nature Needs Her Daughters Ingrid Albion 40 min keynote Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service 9.50 The quest for identity.... the bleating heart of John Pastorelli 20 min paper Interpretation Ochre Learning 10.10 Morning Tea (20 mins) 10.30 Curator’s perspective: Local Government and Lynette Nilaweera & Brooke Wandin 40 min keynote the Community Yarra Ranges Regional Museum & Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation 11.10 We'll Just Bung a Sign In! Gary Estcourt 20 min paper John Holland Rail 11.30 Design serendipity: lessons learned from years David HuXtable 20 min paper of trying LookEar 11.50 Now You See Us – Public Art and Paper Mary-Jane Walker 20 min paper Taxidermy to Interpret the Anthropocene at The School of Lost Arts the Local Level 12.10 Speakers panel All morning speakers Questions 12.30 Lunch (60 mins) 13.30 Welcome by session sponsor Beata Kade Art of Multimedia 13.40 Mixed Realities: How new tech will ruin Robbie McEwen 20 min paper everything but offer stunning interpretive tools. The Floor is Lava 14.00 Sustainable story-telling in a former goldrush -

Part of the Furniture

PART OF THE FURNITURE Moments in the History of the Federated Furnishing Trades Society of Victoria LYNN BEATON MUP|© Melbourne University Publishing MUP CUSTOM An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Ltd 187 Grattan Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053 Australia [email protected] www.mup.com.au First published 2007 Text © Lynn Beaton 2007 Images © Individual copyright holders 2007 Design and typography © Melbourne University Publishing Ltd 2007 Designed by Phil Campbell Typeset in New Baskerville Printed in Australia by Griffin Press This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Beaton, Lynn. Part of the furniture: moments in the history of the Federated Furnishing Trades Society of Victoria. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 9780522854169 (hbk.). 1. Federated Furnishing Trades Society of Australasia. Victorian Branch—History. 2. Furniture workers—Labor unions—Victoria— History. 3. Furniture industry and trade—Victoria—History. I. Title. 331.88184109945 CONTENTS Preface vii Image Acknowledgements x Introduction xi Chapter 1 1 Beginnings Chapter 2 27 Crafting a Place in the Nation Chapter 3 62 Becoming Proletarian Chapter U 91 Depression Between Wars Chapter 5 122 Post-War Divisions Chapter 6 152 Into the Fray Chapter 7 179 Tricky Amalgamation Chapter 8 212 Schism and Integration Chapter 9 266 New Directions References 266 Index 270 PREFACE While reading the Federated Furnishing Trades Society of Victoria’s history I was struck by how much I didn’t know about a Union I’ve been part of for nearly two decades. -

Victorian Heritage Database Place Details - 30/9/2021 COUNCIL CHAMBERS

Victorian Heritage Database place details - 30/9/2021 COUNCIL CHAMBERS Location: 233-247 LITTLE COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE, MELBOURNE CITY Heritage Inventory (HI) Number: H7822-1753 Listing Authority: HI Heritage Inventory Citation STATEMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE: The Melbourne Town Hall was constructed between 1867 and 1872 on the site of the earlier Town Hall which had been designed by James Blackburn and completed in 1853. A competition was held for the new building between 1864 and 1866 and was won by Joseph Reed. The building included a public hall, administrative offices, Lord Mayor's rooms and Council Chamber. The portico was added in 1887-8 and was designed by Joseph Reed's firm at the time, Reed Henderson and Smart. The Administration Building was constructed in 1908-10 to accommodate the Council's growing administrative needs, and was the result of another competition. Grainger, Kennedy and Little won the competition and designed the interior, with the second prize won by JJ and EJ Clark who designed the The Melbourne Town Hall is of historic and social significance as the civic centre of Melbourne since 1867. It represents in its physical form the changing needs and aspirations of the citizens of Melbourne. Externally the building is of architectural importance as an early application of the French Second Empire style in Victoria as designed by prominent architect Joseph Reed. Internally, the hall and Collins Street entry foyer are of significance as an intact example of a major public space of the 1920s which retain original fittings and decoration. The Napier Waller murals in the hall are The organ is of technical or scientific significance as an intact and scarce example of 1920s British organ-building craftsmanship. -

News from the Collections

News from the collections Grainger Museum reopening Melbourne Conservatorium of The Grainger Museum officially Music; Dr Peter Tregear of Monash re-opened on Friday 15 October, University; and Brian Allison and following a seven-year closure. Astrid Krautschneider, Curators of Over the past few years substantial the Grainger Museum. conservation works were carried out The Grainger Museum is located on the heritage-registered building on Royal Parade, near Gate 13, under the supervision of conservation Parkville Campus. The opening architects Lovell Chen, along with hours are Tuesday to Friday 1pm to improvements to the facilities for 4.30pm and Sunday 1pm to 4.30pm. visitors, collections and staff. The new Closed Monday and Saturday, public suite of exhibitions, curated by the holidays and Christmas through Grainger Museum staff and designed January. Percy’s Café is open 8am to by Lucy Bannyan of Bannyan Wood 5pm, Monday to Friday. For further Design, explore Grainger’s life, times information or to join the mailing list and work. Funding was provided see www.grainger.unimelb.edu.au. by the University, the University Library, the University Annual MacPherson, Ormond Professor of G.W.L. Marshall-Hall: Appeal, bequests and donors. The Music and Director of the Melbourne A symposium guest speaker at the launch was Conservatorium of Music. Professor The collections of the Grainger Professor Malcolm Gillies, Vice- Gillies’ keynote paper ‘Grainger Museum provide an invaluable Chancellor of London Metropolitan 50 years on’ explored Percy Grainger’s research resource that extend far University and a leading Grainger current place in both the world of beyond the life and music of Percy scholar. -

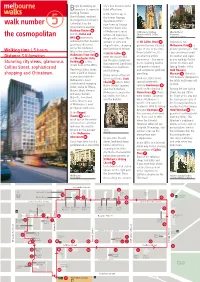

Walk Number the Cosmopolitan

egin by walking up city’s fine theatresat the BSwanston St, opposite ticket office here. bustling Flinders A little further up, is Street Station, and past the former Georges the magnificent St Paul’s department store – walk number 5 Cathedral. Pass the now home to George monument to explorer Patterson Bates (one Matthew Flinders 1 of Melbourne’s most St Michaels Uniting Westin Hotel and the Burke and famous ad agencies). Church and 101 Collins forecourt, the cosmopolitan Street Swanston Street Wills 2 monument Mingle with smart office dedicated to their doomed workers in suits and of 101 Collins Street 10 , Opposite is the journey of discovery elegant ladies, shopping go into the neo-classical Melbourne Club 15 , a across the continent. and lunching at leisure. foyer. Home to the city’s private gentleman’s club Walking time 1.5 hours Take in the view of the At 161 On Collins 7 , financial whizzes, it’s - you can almost smell Melbourne Town Hall 3 an amazing artistic the leather and cigars Distance 3 Kilometres and Manchester Unity enter the atrium and see the glass sculptures experience – four water as you walk by. On the Stunning city views, glamorous Building 4 , a deco pools, stunning marble corner of Collins and dream built in the 1930s. that represent Significant Collins Street, sophisticated Melbourne Landmarks and granite columns Spring Streets, is the Reaching Collins Street, and Buildings. and sumptuous gold leaf Gold Treasury shopping and Chinatown. catch a whiff of Chanel panelling. Museum 16 , Victoria’s as you turn right into At the corner of Russell Back on Collins Street, ‘Old Treasury’ designed in Melbourne’s most Street you’ll pass Scots several nineteenth the 1850s by 19-year-old sophisticated shopping Church 8 , where Dame century townhouses 11 J.J.Clark. -

The Journal of Professional Historians

Issue six, 2018 six, Issue The Journal of of The Journal Circa Professional Historians CIRCA THE JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL HISTORIANS ISSUE SIX, 2018 PHA Circa The Journal of Professional Historians Issue six, 2018 Circa: The Journal of Professional Historians Issue six, 2018 Professional Historians Australia Editor: Christine Cheater ISSN 1837-784X Editorial Board: Francesca Beddie Carmel Black Neville Buch Sophie Church Brian Dickey Amanda McLeod Emma Russell Ian Willis Layout and design: Lexi Ink Design Printer: Moule Printing Copyright of articles is held by the individual authors. Except for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted by the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the author. Address all correspondence to: The Editor, Circa Professional Historians Australia PO Box 9177 Deakin ACT 2600 [email protected] The content of this journal represents the views of the contributors and not the official view of Professional Historians Australia. Cover images: Front cover, top row, left to right: Newman Rosenthal and Thomas Coates, Portuguese Governor of Dili and staff, Margaret Williams-Weir. Bottom: 8 Hour procession, 1866. Back cover, top: Mudgee policeman and tracker Middle row, left to right: Woman and maid, HEB Construction workers. Bottom: Walgett tracker and police Contents EDITORIAL . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. IV Part one: Explorations Pathfinders: NSW Aboriginal Trackers and Native Title History MICHAEL BENNETT. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Working in the Dirt SANDRA GORTER .. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ..11 Part two: Discoveries Unpacking a Legend MARGARET COOK AND ANNAbeL LLOYD . .21 Not Just White Proddy Boys: The Melbourne Faculty of Education 1903-1973 JULIET ELLA FLesCH . -

Melbourne City Map BERKELEY ST GARDENS KING WILLIAM ST Via BARRY ST

IAN POTTER MUSEUM OF ART STORY ST Accessible toilet Places of interest Bike path offroad/onroad GRAINGER ELGIN ST MUSEUM To BBQ Places of worship City Circle Tram route Melb. General JOHNSON ST CINEMA BRUNSWICK ST Cemetary NOVA YOUNG ST with stops NAPIER ST MACARTHUR SQUARE GEORGE ST Cinema Playground GORE ST VICTORIA ST SMITH ST Melbourne Visitor UNIVERSITY KATHLEEN ROYAL SYME FARADAY ST WOMEN’S ROYAL OF MELBOURNE CENTRE Community centre Police Shuttle bus stop HOSPITAL MELBOURNE 6 HOSPITAL ROYAL FLEMINGTON RD DENTAL Educational facility Post Office Train station HOSPITAL HARCOURT ST GRATTAN ST MUSEO ITALIANO CULTURAL CENTRE BELL ST GREEVES ST Free wifi Taxi rank Train route 7 LA MAMA THEATRE CARDIGAN ST LYGON ST BARKLY ST VILLIERS ST ROYAL PDE Hospital Theatre ARDEN ST ST DAVID ST Tram route with CARLTON ST platform stops GRATTAN ST Major Bike Share stations Toilet MOOR ST Tram stop zone WRECKYN ST SQUARE MOOR ST BAILLIE ST ARTS HOUSE, To Sydney CARLTON Marina Visitor information MEAT MARKET UNIVERSITY STANLEY ST Melbourne city map BERKELEY ST GARDENS KING WILLIAM ST via BARRY ST centre LEICESTER ST DRYBURGH ST PELHAM ST BLACKWOOD ST Sydney Rd PROVOST ST CONDELL ST Parking COURTNEY ST Accessible toilet Places of interest BikeThis path mapABBOTSFORD ST offroad/onroadis not to scale ELIZABETH ST QUEENSBERRY ST PIAZZA HANOVER ST LINCOLN PELHAM ST ITALIA BEDFORD ST CHARLES ST BBQ Places of worship 0 City Circlemetres Tram route360 BERKELEY ST SQUARE ARGYLE PELHAM ST To Eastern BARRY ST SQUARE Fwy, Yarra with stops IMAX Ranges via ARTS HOUSE, -

History of LGBTIQ+ Victoria Pdf 8.3 MB

A History of LGBTIQ+ Victoria in 100 Places and Objects Graham Willett Angela Bailey Timothy W. Jones Sarah Rood MARCH 2021 If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Australian Queer Archives email: [email protected] © Australian Queer Archives and the State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2021 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the Australian Queer Archives. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including logos. To view a copy of this licence, visit http:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-0-6451287-1-0 (pdf/online/MS word) ISBN 978-0-6451287-0-3 (print) This publication may be of assistance to you but the Australian Queer Archives and the State of Victoria do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Design and layout by Green Scribble Cover images listed in the image credit section Funded by Heritage Victoria, Department of Environment Land, Water and Planning. Ministerial Foreword History shapes our identity and reminds us of who we are. For the LGBTIQ+ community, the past can be a difficult place. Today in Victoria, LGBTIQ+ people enjoy the positive transformations hard won by the 1970s Gay Liberation Movement and its public demands for equal rights. -

Melbourne׳S Rockin׳ Venues

Melbourne’s Rockin’ Venues The Palais Theatre Most punters in Melbourne have had a Palais experience at least once. Maybe you saw The Rolling Stones in ’66, or went to Jesus Christ Superstar or The Andrew Durant Memorial Concert in the 70’s? Today it remains a grand old dame, still hosting iconic shows. Here is a cool link to its history: https://palaistheatre.com.au/venue/venue-history Armstrong Studios Basically, it was our Abbey Road. Whispering Jack was recorded here, and many other acts came to avail themselves of its world class facilities. (U2, Paul McCartney, Madonna, Bob Dylan, Split Enz, Crowded House and many more) Bill Armstrong started out in a terraced house in South Melbourne before moving operations to an old butter factory in Bank street. The work recorded here is a staggering list of Australian Rock & Entertainment. Wikipedia has the story: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armstrong_Studios Festival Hall The “House of Stoush” in West Melbourne has hosted Wrestling, The Beatles, Boxing, Jethro Tull, Roller Derbies, Black Sabbath, Chuck Berry, The Bee Gees, Roy Orbison & hundreds more eclectic shows over its six-decade history. Recently, it was saved from high rise ‘re-development’ by concerned councils & ratepayers. https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/archives/boxing-ballroom-dancing-and-the-bishop-of-coventry- festival-hall-and-stadiums-pty-ltd/ http://www.jpgr.co.uk/ven_melbourne.html Melbourne Town Hall A strange rock venue you might think, but The Beatles & Abba have both waved at the crowds from its balcony. If you take the MTH tour, you can wave from there too! https://whatson.melbourne.vic.gov.au/Whatson/tours/ground/Pages/b974dd12-59a5-4de8- a7b0-d8c2f82385ec.aspx?_ga=2.257283979.127260475.1547370975- 471500608.1542539087 Swanston St/ACDC Lane It takes a flatbed truck, a great song, a film crew from Countdown, and a rock band with bagpipes to create one of the greatest Aussie anthems of all time, It’s a Long Way to the Top (If you wanna Rock n’ Roll) This is where ACDC made one of their most remembered film clips in the 70’s. -

150 Years of the Melbourne Town Hall

You are cordially invited… Curator You are cordially invited… Andrew Stephens is an arts writer, editor and curator. 150 YEARS OF THE MELBOURNE TOWN HALL November 2020 His work is published in The Age, Art Monthly Australasia, November 2020 to January 2021 Art Guide Australia and other arts magazines. He is editor to January 2021 of Imprint for the Print Council of Australia. City Gallery City Gallery Melbourne Town Hall Thanks to Melbourne Town Hall The Art and Heritage Collection team for guiding this melbourne.vic.gov.au/ project, commissioned artist Patrick Pound, Stephen melbourne.vic.gov.au/ You are cordially invited to citygallery Banham, Hilary Ericksen, former Lord Mayor Lecki Ord, citygallery former Councillor Lorna Hannan, Councillor Rohan explore Melbourne Town Hall’s Leppert, Dr Fiona Foley, Sonja Peter, Jane Sharwood, 150 years as the heart-centre of ISBN 978–1–74250–914–3 Kate Gorringe-Smith, Luke Rogers, Miles Brown, Bryony Jackson, Tristan Meecham, Destiny Deacon, Virginia city life. This majestic building Fraser, Naretha Williams, Andrew Daddo, Peter Lindeman and Catherine Reade. Special thanks to Kenneth, Timothy has hosted an extraordinary and Adelaide. array of people and events since Inside Left Inside Right opening in August 1870, and it The Beatles at Reed and Barnes Melbourne Town Architects and remains vital in shaping the city’s Hall, 16 June 1964 Surveyors, collective psyche – the seat of John Lamb Elizabeth Street, Melbourne Courtesy Nine governance, political debate Melbourne Town Publishing Hall – section I and K, and cultural activity. 1 July 1867 Ink on paper 89.3 x 120.5 cm City of Melbourne Art and Heritage Collection Enter here… Imagine Melbourne Town Hall as an immense time machine.1 Through this portal, we might travel from one moment in time to the next, seeing all the events and people this majestic building has ever hosted, gazing upon an extraordinary array of human feeling and endeavour. -

Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo

melbourne opera Part One of e Ring of the Nibelung WAGNER’S Regent Theatre Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Richard Wagner Society (VIC) • Wagner Society (nsw) Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand (RISE) Fund melbourneopera.com Classic bistro wine – ethereal, aromatic, textural, sophisticated and so easy to pair with food. They’re wines with poise and charm. Enjoy with friends over a few plates of tapas. debortoli.com.au /DeBortoliWines melbourne opera WAGNER’S COMPOSER & LIBRETTIST RICHARD WAGNER First performed at Munich National Theatre, Munich, Germany on 22nd September 1869. Wotan BASS Eddie Muliaumaseali’i Alberich BARITONE Simon Meadows Loge TENOR James Egglestone Fricka MEZZO-SOPRANO Sarah Sweeting Freia SOPRANO Lee Abrahmsen Froh TENOR Jason Wasley Donner BASS-BARITONE Darcy Carroll Erda MEZZO-SOPRANO Roxane Hislop Mime TENOR Michael Lapina Fasolt BASS Adrian Tamburini Fafner BASS Steven Gallop Woglinde SOPRANO Rebecca Rashleigh Wellgunde SOPRANO Louise Keast Flosshilde MEZZO-SOPRANO Karen Van Spall Conductors Anthony Negus, David Kram FEB 5, 21 Director Suzanne Chaundy Head of Music Raymond Lawrence Set Design Andrew Bailey Video Designer Tobias Edwards Lighting Designer Rob Sowinski Costume Designer Harriet Oxley Set Build & Construction Manager Greg Carroll German Language Diction Coach Carmen Jakobi Company Manager Robbie McPhee Producer Greg Hocking AM MELBOURNE OPERA ORCHESTRA The performance lasts approximately 2 hours 25 minutes with no interval. Principal Sponsor: Henkell Brothers Investment Managers Sponsors: Dr Alastair Jackson AM • Lady Potter AC CMRI • Angior Family Foundation Robert Salzer Foundation • Dr Douglas & Mrs Monica Mitchell • Roy Morgan Restart Investment to Sustain and The role of Loge, performed by James Egglestone, is proudly supported by Expland (RISE) Fund – an Australian the Richard Wagner Society of Victoria. -

EPICURE at Melbourne Town Hall T

EPICURE at Melbourne Town Hall t. +613 9658 9779 [email protected] epicure.com.au ABOUT US FOOD PHILOSOPHY EVENT SPACES GALLERY ADDITIONAL INFO CONTACT EPICURE THE HEART OF THE CITY NEXT > EPICURE at Melbourne Town Hall t. +613 9658 9779 [email protected] epicure.com.au ABOUT US FOOD PHILOSOPHY EVENT SPACES GALLERY ADDITIONAL INFO CONTACT EPICURE WEO LC ME TO EpICURE AT THE MELBOURNE TOWN HALL For over 135 years, Melbourne Town Hall has elegance of the Yarra and Melbourne Rooms. been at the heart of events which have shaped Sip a cocktail while you look out over Swanston the city’s future and celebrated our milestones. Street from the famous Portico Balcony. Here, Federation was debated, Nellie Melba The Melbourne Town Hall is at the heart of debuted and the Beatles greeted an adoring Melbourne’s event scene and has shaped the crowd. The grand interiors echo with city’s future. It is a versatile venue with a variety countless celebrations, gala occasions, festivals, of function spaces that caters to large scale gala commemorations—the imprints of a community dinners for 700 through to intimate wedding life across generations. ceremonies on the Portico Balcony overlooking the city skyline and boardroom meetings in one Located in the heart of the CBD, Melbourne of the smaller spaces. Town Hall is the showcase destination for the city’s cultural and civic life. It plays host to theatrical performances, wedding ceremonies and receptions, exhibitions, corporate launches, school concerts, conferences and cocktail parties. Embracing events of 10 to 2000 people, Melbourne Town Hall offers a superb suite of rooms and meeting spaces.