Religious Worship in Kent-The Census

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIS Bulletin Issue 77

Scientific Instrument Society Bulletin June No. 77 2003 Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society ISSN 0956-8271 For Table of Contents, see back cover President Gerard Turner Vice-President Howard Dawes Honary Committee Gloria Clifton, Chairman Alexander Crum Ewing, Secretary Simon Cheifetz,Treasurer Willem Hackmann, Editor Peter de Clercq, Meetings Secretary Ron Bristow Tom Lamb Tom Newth Alan Stimpson Sylvia Sumira Trevor Waterman Membership and Administrative matters The Executive Officer (Wg Cdr Geoffrey Bennett) 31 High Street Stanford in the Vale Tel: 01367 710223 Faringdon Fax: 01367 718963 Oxon SN7 8LH e-mail: [email protected] See outside back cover for information on membership Editorial Matters Dr.Willem Hackmann Sycamore House The PLaying Close Tel: 01608 811110 Charlbury Fax: 01608 811971 Oxon OX7 3QP e-mail: [email protected] Society’s Website www.sis.org.uk Advertising See “summary of Advertising Services’ panel elsewhere in this Bulletin. Further enquiries to the Executive Officer, Design and printing Jane Bigos Graphic Design 95 Newland Mill Tel: 01993 209224 Witney Fax: 01993 209255 Oxon OX28 3SZ e-mail: [email protected] Printed by The Flying Press Ltd,Witney The Scientific Instrument Society is Registered Charity No. 326733 © The Scientific Instrument Society 2003 Editorial Spring Time September issue.I am still interested to hear which this time will be published elec- I am off to the States in early June for three from other readers whether they think this tronically on our website.He has been very weeks so had to make sure that this issue project a good idea. industrious on our behalf. -

This Clock Is a Rather Curious the Movement Is That of a a Combination

MINERAL GLASS CRYSTALS 36 pc. Assortment Clear Styrene Storage Box Contains 1 Each of Most Popular Sizes From 19.0 to 32.0 $45.00 72 pc. Assortment Clear Styrene Storage Box Contains 1 Each of Most Popular Refills Available Sizes From 14.0 to 35.0 On All Sizes $90.00 :. JJl(r1tvfolet Gfa:ss A~hesive Jn ., 'N-e~ilie . Pofot Tobe · Perfect for MinenifGlass Crystals - dire$ -iA. secondbn ~un or ultraviolet µgh{'DS~~~ cfa#ty as gl;lss. Stock Up At These Low Prices - Good Through November 10th FE 5120 Use For Ronda 3572 Y480 $6.50 V237 $6.50 Y481 $6.95 V238 $6.95 Y482 $6.95 V243 $6.95 51/2 x 63/4 $9.95 FREE - List of Quartz Movements With Interchangeability, Hand Sizes, Measurements, etc. CALL TOLL FREE 1-800-328-0205 IN MN 1-800-392-0334 24-HOUR FAX ORDERING 612-452-4298 FREE Information Available *Quartz Movements * Crystals & Fittings * * Resale Merchandise * Findings * Serving The Trade Since 1923 * Stones* Tools & Supplies* VOLUME13,NUMBER11 NOVEMBER 1989 "Ask Huck" HOROLOGICAL Series Begins 25 Official Publication of the American Watchmakers Institute ROBERT F. BISHOP 2 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE HENRY B. FRIED QUESTIONS & ANSWERS Railroad 6 Emile Perre t Movement JOE CROOKS BENCH TIPS 10 The Hamilton Electric Sangamo Clock Grade MARVIN E. WHITNEY MILITARY TIME 12 Deck Watch, Waltham Model 1622-S-12 Timepieces WES DOOR SHOP TALK 14 Making Watch Crystals JOHN R. PLEWES 18 REPAIRING CLOCK HANDS 42 CHARLES CLEVES OLD WATCHES 20 Reality Sets In ROBERT D. PORTER WATCHES INSIDE & OUT 24 A Snap, Crackle, & Pop Solution J.M. -

The Folkestone School for Girls

Buses serving Folkestone School for Girls page 1 of 6 via Romney Marsh and Palmarsh During the day buses run every 20 minutes between Sandgate Hill and New Romney, continuing every hour to Lydd-on-Sea and Lydd. Getting to school 102 105 16A 102 Going from school 102 Lydd, Church 0702 Sandgate Hill, opp. Coolinge Lane 1557 Lydd-on-Sea, Pilot Inn 0711 Hythe, Red Lion Square 1618 Greatstone, Jolly Fisherman 0719 Hythe, Palmarsh Avenue 1623 New Romney, Light Railway Station 0719 0724 0734 Dymchurch, Burmarsh Turning 1628 St Mary’s Bay, Jefferstone Lane 0728 0733 0743 Dymchurch, High Street 1632 Dymchurch, High Street 0733 0738 0748 St. Mary’s Bay, Jefferstone Lane 1638 Dymchurch, Burmarsh Turning 0736 0741 0751 New Romney, Light Railway Station 1646 Hythe, Palmarsh Avenue 0743 0749 0758 Greatstone, Jolly Fisherman 1651 Hythe, Light Railway Station 0750 0756 0804 Lydd-on-Sea, Pilot Inn 1659 Hythe, Red Lion Square 0753 0759 0801 0809 Lydd, Church 1708 Sandgate Hill, Coolinge Lane 0806 C - 0823 Lydd, Camp 1710 Coolinge Lane (outside FSG) 0817 C - Change buses at Hythe, Red Lion Square to route 16A This timetable is correct from 27th October 2019. @StagecoachSE www.stagecoachbus.com Buses serving Folkestone School for Girls page 2 of 6 via Swingfield, Densole, Hawkinge During the daytime there are 5 buses every hour between Hawkinge and Folkestone Bus Station. Three buses per hour continue to Hythe via Sandgate Hill and there are buses every ten minutes from Folkestone Bus Station to Hythe via Sandgate Hill. Getting to school 19 19 16 19 16 Going -

Proposed Amalgamation of Hythe Community School and Hythe, St Leonard's Church of England Junior

Proposed amalgamation of Hythe Community School and Hythe, St Leonard's Church of England Junior (Voluntary controlled) School, Shepway - Outcome of public consultation By: Graham Badman, Strategic Director Education and Libraries and Leyland Ridings, Cabinet Member for School Organisation and Early Years to Cabinet - 11 July 2005 Summary: This report sets out the results of the public consultation for the amalgamation of Hythe Community School and Hythe, St Leonard’s Church of England (Voluntary Controlled) School. It seeks Cabinet’s agreement to the issuing a public notice for the closure of both schools and assisting the interim governing body in issuing a public notice for the establishment of a 2FE all through (Voluntary Controlled) Primary School on the site of Hythe Community School Introduction 1. (1) The School Organisation Advisory Board at its meeting on 17 March 2005 supported the undertaking of a public consultation on the proposal to amalgamate Hythe Community School and Hythe St Leonard's CEJ (VC) School. (2) Hythe Community and Hythe St Leonard’s CE (VC) Junior Schools are both two form entry schools having an entry of up to 56 pupils in each year group. (3) Hythe St Leonard’s School currently operates in inadequate Victorian buildings with the majority of classrooms being too small and either too hot or too cold. Its playing fields are located on land at Hythe Community School. Hythe Community School is an infant school in SEAC buildings. (4) The schools are situated on separate sites with a distance of approximately 200m between them. A map is attached as Appendix 1 (please contact Geoff Mills on 01622 694289 or Karen Mannering on 01622 694367 for a copy of the map). -

The Turret Clock Keeper's Handbook Chris Mckay

The Turret Clock Keeper’s Handbook (New Revised Edition) A Practical Guide for those who Look after a Turret Clock Written and Illustrated by Chris McKay [ ] Copyright © 0 by Chris McKay All rights reserved Self-Published by the Author Produced by CreateSpace North Charleston SC USA ISBN-:978-97708 ISBN-0:9770 [ ] CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................................................................11 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 12 The Author ............................................................................................................................... 12 Turret clocks— A Brief History .............................................................................................. 12 A Typical Turret Clock Installation.......................................................................................... 14 How a Turret Clock Works....................................................................................................... 16 Looking After a Turret Clock .................................................................................................. 9 Basic safety... a brief introduction................................................................................... 9 Manual winding .............................................................................................................. 9 Winding groups ............................................................................................................. -

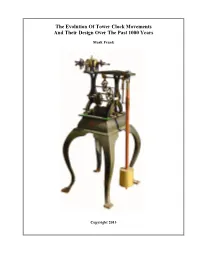

The Evolution of Tower Clock Movements and Their Design Over the Past 1000 Years

The Evolution Of Tower Clock Movements And Their Design Over The Past 1000 Years Mark Frank Copyright 2013 The Evolution Of Tower Clock Movements And Their Design Over The Past 1000 Years TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and General Overview Pre-History ............................................................................................... 1. 10th through 11th Centuries ........................................................................ 2. 12th through 15th Centuries ........................................................................ 4. 16th through 17th Centuries ........................................................................ 5. The catastrophic accident of Big Ben ........................................................ 6. 18th through 19th Centuries ........................................................................ 7. 20th Century .............................................................................................. 9. Tower Clock Frame Styles ................................................................................... 11. Doorframe and Field Gate ......................................................................... 11. Birdcage, End-To-End .............................................................................. 12. Birdcage, Side-By-Side ............................................................................. 12. Strap, Posted ............................................................................................ 13. Chair Frame ............................................................................................. -

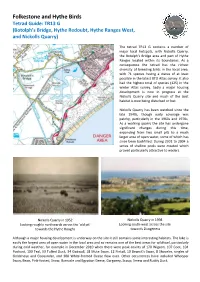

Botolph's Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West And

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 G (Botolph’s Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West, and Nickolls Quarry) The tetrad TR13 G contains a number of major local hotspots, with Nickolls Quarry, the Botolph’s Bridge area and part of Hythe Ranges located within its boundaries. As a consequence the tetrad has the richest diversity of breeding birds in the local area, with 71 species having a status of at least possible in the latest BTO Atlas survey. It also had the highest total of species (125) in the winter Atlas survey. Sadly a major housing development is now in progress at the Nickolls Quarry site and much of the best habitat is now being disturbed or lost. Nickolls Quarry has been watched since the late 1940s, though early coverage was patchy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. As a working quarry the site has undergone significant changes during this time, expanding from two small pits to a much larger area of open water, some of which has since been backfilled. During 2001 to 2004 a series of shallow pools were created which proved particularly attractive to waders. Nickolls Quarry in 1952 Nickolls Quarry in 1998 Looking roughly northwards across the 'old pit' Looking south-west across the site towards the Hythe Roughs towards Dungeness Although a major housing development is underway on the site it still contains some interesting habitats. The lake is easily the largest area of open water in the local area and so remains one of the best areas for wildfowl, particularly during cold weather, for example in December 2010 when there were peak counts of 170 Wigeon, 107 Coot, 104 Pochard, 100 Teal, 53 Tufted Duck, 34 Gadwall, 18 Mute Swan, 12 Pintail, 10 Bewick’s Swan, 8 Shoveler, singles of Goldeneye and Goosander, and 300 White-fronted Geese flew over. -

New Romney|Lydd|Rye

Dover|Folkestone|Hythe|New Romney|Lydd|Rye 102 From 29 October 2018 Mondays to Fridays Dover Pencester Rd Stop X - - 0620 0650 0715 0740 0800 0820 0840 0900 0920 Plough Inn - - 0628 0658 0723 0748 0808 0828 0848 0908 0928 Capel Capel Street - - 0633 0703 0728 0753 0813 0833 0853 0913 0933 Hill Road Keyes Place - - 0636 0706 0731 0756 0816 0836 0856 0916 0936 Folkestone Bus Station arr - - 0645 0715 0740 0808 0828 0848 0908 0928 0948 Folkestone Bus Stn Bay D1 - 0610 0650 0720 0745 0813 0833 0853 0913 0933 0953 Sandgate Memorial - 0616 0656 0726 0752 0820 0840 0900 0920 0940 1000 Seabrook Fountain - 0620 0700 0730 0757 0825 0845 0905 0925 0945 1005 Hythe Red Lion Square - 0627 0707 0737 0805 0838 0858 0918 0938 0958 1018 Hythe Palmarsh Avenue - 0632 0712 0742 0810 0843 0903 0923 0943 1003 1023 Dymchurch Burmarsh Turning - 0637 0717 0747 0815 0848 0908 0928 0948 1008 1028 Dymchurch High Street - 0640 0720 0750 0819 0852 0912 0932 0952 1012 1032 St Mary's Bay Jefferstone Lane - 0645 0725 0755 0825 0858 0918 0938 0958 1018 1038 New Romney Ship Hotel 0626 - - 0803 - - - - - - New Romney Light Railway Stn 0629 0652 0733 - 0839 0906 0926 0946 1006 1026 1046 Littlestone Queens Road - - - - - 0908 0928 - 1008 1028 - Greatstone Jolly Fisherman 0634 - 0738 - 0844 - - 0951 - - 1051 Lydd-on-Sea Pilot Inn 0641 - 0746 - 0852 - - 0959 - - 1059 Lydd Church 0648 - 0755 - 0901 - - 1008 - - 1108 Lydd Camp 0649 - 0757 - 0903 - - 1010 - - 1110 Camber Sands Holiday Park 0659 - 0807 - 0920 - - 1020 - - 1120 Rye Rail Station Stop B 0717 - 0828 - 0941 - - 1041 - -

FINE CLOCKS Wednesday 13 December 2017

FINE CLOCKS Wednesday 13 December 2017 FINE CLOCKS Wednesday 13 December at 2pm 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Saturday 9 December +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 James Stratton M.R.I.C.S Monday to Friday 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax + 44 (0) 20 7468 8364 8.30am to 6pm Sunday 10 December To bid via the internet please [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 11am to 3pm visit bonhams.com Monday 11 December Administrator As a courtesy to intending 9am to 4.30pm Please note that bids should be Vanessa Howson bidders, Bonhams will provide a Tuesday 12 December submitted no later than 4pm on + 44 (0) 20 7468 8204 written Indication of the physical 9am to 4.30pm the day prior to the sale. [email protected] condition of lots in this sale if a Wednesday 13 December New bidders must also provide request is received up to 24 9am to 12pm proof of identity when submitting hours before the auction starts. bids. Failure to do this may result This written Indication is issued SALE NUMBER in your bids not being processed. subject to Clause 3 of the Notice 24222 to Bidders. Bidding by telephone will only be CATALOGUE accepted on lots with a low Please see back of catalogue estimate in excess of £1,000 for important notice to bidders £20.00 Live online bidding is ILLUSTRATIONS available for this sale Front cover: Lot 116 Please email [email protected] Back cover: Lot 53 with “Live bidding” in the subject Inside front cover: Lot 102 line 48 hours before the auction Inside back cover: Lot 115 to register for this service. -

The History of the Church Clock St Pauls Church Woodhouse Eaves Leicestershire

The History Of The Church Clock St Pauls Church Woodhouse Eaves Leicestershire. By Maria Jansen Page 1 of 16 Introduction There has always been a mystery surrounding the Church Clock, or Village Clock as it was sometimes known. The information contained in this research seeks to solve some of these and has recently unearthed some interesting and informative old documents, copies of which are referred to in this document and can be found in the Appendices. Design St Paul’s Church Woodhouse Eaves and St Peter’s Copt Oak were two of many of the churches designed by architect William Railton. For these two local churches he used the same design as can be seen at the bottom of original sketch ‘Design of the churches at Woodhouse Eaves and Copt Oak of Charnwood Forest Leicestershire’ [Figure 1] and were built about the same time in 1836/7. Figure 1: Copy of William Railton original architect design 18351 1 ‘Design of the Churches at Woodhouse Eaves and Copt Oak, on Charnwood Forest, Leicestershire by William Railton’, Incorporated Church Building Society (ICBS), Lambeth Palace Library online [http://images.lambethpalacelibrary.org.uk/luna/servlet/s/ubaajd] Page 2 of 16 St Paul’s and St Peter churches were not originally designed with a clock installed, as can be seen in the original design. However St Paul’s has undergone many alterations over the years, including the installation of the clock and two clock faces. St Peter at Copt Oak [Figure 2] remains today with no clock installed and with the original ‘window’, hood moulds and foliage label stops, which can be seen clearly over the front door and triple lancet bell openings on each face with parapet and pinnacles. -

Turret Clock Tour BHI Ipswich Branch – Part 1 Ian Coote MBHI

Turret Clock Tour BHI Ipswich Branch – Part 1 Ian Coote MBHI The Ipswich Branch has organised an annual turret clock tour for many years, the last two of them centred on Braintree, Essex. This article combines the two tours by points of interest, rather than chronologically. Figure 3. Great Leighs round tower. Figure 5. Boreham clock and sundial. Figure 1. Braintree clock as seen on the 2016 turret tour. Figure 2. Braintree St Michael’s as found. St Michael’s Braintree Sometime in 2016, a redundant clock movement was complete. It was decided to restore it to working order taken from the church muniments room, where it had with a view to eventually displaying it in the church. Figure 4. Great Leighs clock by Tucker. been gathering dust for 80 years, with the intention of Our 2016 turret tour began in Rod’s garage. By that disposing of it for scrap. A parochial church council (PCC) time, a local woodturner had made two new barrels member, Rod Davey, refused to allow such a travesty and which were reassembled on to their arbors with new Great Leighs stowed it safely in his own garage. bronze bearings: the originals were iron, and in a poor Tucker, of 42 Theobald’s Road, London, is often said He knew nothing about clocks, but realised that this state. to be a recycler of clocks, adding his own name plate, Figure 6. Inspecting the Boreham clock. was an interesting old mechanism and began looking for Apart from re-bushing two or three pivot holes and a but I have only encountered clocks with his name cast advice. -

Situation of Polling Stations

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Folkestone & Hythe District Council Election of the Police and Crime Commissioner for the Kent Police Area Thursday 6 May 2021 The situation of polling stations is as follows: Station Situation of Polling Station Description of persons entitled to vote Number Grace Taylor Hall, 126 Lucy Avenue, Folkestone, 1 BR1-1 to BR1-3212 CT19 5UH St Georges Church Hall, Audley Road, 2 CH1-1 to CH1-549 Folkestone, CT20 3QA 1st Cheriton Scout Group HQ, Rear of 24 Hawkins 3 CH2-1 to CH2-2904 Road, Folkestone, CT19 4JA All Souls Church Hall, Somerset Rd, Folkestone, 4 CH3-1 to CH3-3295 CT19 4NW St Andrews Methodist Church Hall, Surrenden 5 CH4-1 to CH4-2700 Road, Folkestone, CT19 4DY The Salvation Army Citadel, Canterbury Road, 6 EF1-1 to EF1-2878 Folkestone, CT19 5NL St Johns Church Hall, St Johns Church Road, 7 EF2-1 to EF2-2755 Folkestone, CT19 5BQ Wood Avenue Library, Wood Avenue, Folkestone, 8 EF3-1 to EF3-2884 CT19 6HS Town Hall, 2 Guildhall Street, Folkestone, CT20 9 FC1-1 to FC1-2396 1DY South Kent Community Church, Formerly the 10 FC2-1 to FC2-2061/1 United Reform Church Hall, Castle Hill Avenue, Folkestone, CT20 2QR Holy Trinity Church Hall, Sandgate Road, 11 FC3-1 to FC3-1948 Folkestone, CT20 2HQ Wards Hotel - (Grimston Gardens Entrance), 39 12 FC4-1 to FC4-1737 Earls Avenue, Folkestone, CT20 2HB Folkestone Baptist Church Hall, Hill Road, 13 FH1-1 to FH1-1714 Folkestone, CT19 6LY Urban Room (Formerly Tourist Information 14 FH2-1 to FH2-927 Centre), Tram Road Car Park, Tram Road, Folkestone, CT20 1QN Dover Road