University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Collection of Short and Nonfiction

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Spring 5-1-2018 Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction Mary Karnes University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Karnes, Mary, "Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction" (2018). Master's Theses. 359. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/359 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unlonely: a Collection of Short and Nonfiction by Mary Ryan Karnes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Angela Ball, Committee Chair Anne Sanow Charles Sumner Justin Taylor ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Angela Ball Dr. Luis Iglesias Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School May 2018 COPYRIGHT BY Mary Ryan Karnes 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT The following short stories and nonfiction essays were produced by the author during her writing career at the University of Southern Mississippi. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following work took shape under the counsel of Steve Barthelme, Anne Sanow, and Justin Taylor, all incredible writers and mentors. Steve pushed me toward adulthood in my writing; Anne encouraged me to take risks and to consider form at every turn; Justin saw my work’s strengths where I could only see it faltering. -

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

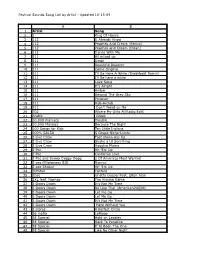

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

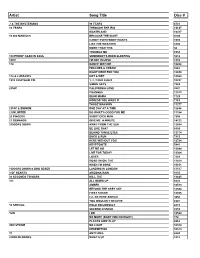

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

The Deadly Affairs of John Figaro Newton Or a Senseless Appeal to Reason and an Elegy for the Dreaming

The deadly affairs of John Figaro Newton or a senseless appeal to reason and an elegy for the dreaming Item Type Thesis Authors Campbell, Regan Download date 26/09/2021 19:18:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/11260 THE DEADLY AFFAIRS OF JOHN FIGARO NEWTON OR A SENSELESS APPEAL TO REASON AND AN ELEGY FOR THE DREAMING By Regan Campbell, B.F.A. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2020 APPROVED: Daryl Farmer, Committee Chair Leonard Kamerling, Committee Member Chris Coffman, Committee Member Rich Carr, Chair Department of English Todd Sherman, Dean College of Liberal Arts Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract Are you really you? Are your memories true? John “Fig” Newton thinks much the same as you do. But in three separate episodes of his life, he comes to see things are a little more strange and less straightforward than everyone around him has been inured to the point of pretending they are; maybe it's all some kind of bizarre form of torture for someone with the misfortune of assuming they embody a real and actual person. Whatever the case, Fig is sure he can't trust that truth exists, and over the course of his many doomed relationships and professional foibles, he continually strives to find another like him—someone incandescent with rage, and preferably, as insane and beautiful as he. i Extracts “Whose blood do you still thirst for? But sacred philosophy will shackle your success, for whatsoever may be your momentary triumph or the disorder of this anarchy, you will never govern enlightened men. -

Ti Dimetrap Album Torrent Download Pirate

t.i. dimetrap album torrent download pirate bay T.i. dimetrap album torrent download pirate bay. Last Updated: 22 May, 2021, EST. Does the Pirate Bay Hide Your Identity? There are basic things everyone should acknowledge before using The Pirate Bay. One of those things is that the website does not hide your identity. It is dependent on the user to come up with ways to protect their identity and ensure they stay safe on the internet. No matter how often you use The Pirate Bay, you don’t want to be caught. There are many ways people can go incognito on Pirate Bay. Unlock entry to ThePirateBay. Works on any device. The most obvious solution to protecting yourself on Pirate Bay is by using a VPN. A VPN is a Verified Private Network that will hide your information and your IP address, so you can surf the web freely. Though this is a great way to use the Pirate Bay Network, users should still be aware that it is not 100% reliable. Pirate Bay users should also use an I2P application to go invisible online. This will help them become as safe and secure as possible. Click the following link to browse The Pirate Bay. Android devices supported. No one, including the Pirate Bay creators, are protected by the site itself. Uploading and downloading the torrents are illegal and a form of copyright infringement. Know what you can be charged with before using The Pirate Bay and make the necessary adjustments to browse safely. How to find forums related to the Pirate Bay. -

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

![3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1496/3-smack-that-eminem-feat-eminem-akon-shady-convict-2571496.webp)

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM thing on Get a little drink on (feat. Eminem) They gonna flip for this Akon shit You can bank on it! [Akon:] Pedicure, manicure kitty-cat claws Shady The way she climbs up and down them poles Convict Looking like one of them putty-cat dolls Upfront Trying to hold my woodie back through my Akon draws Slim Shady Steps upstage didn't think I saw Creeps up behind me and she's like "You're!" I see the one, because she be that lady! Hey! I'm like ya I know lets cut to the chase I feel you creeping, I can see it from my No time to waste back to my place shadow Plus from the club to the crib it's like a mile Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini away Gallardo Or more like a palace, shall I say Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Plus I got pal if your gal is game TaeBo In fact he's the one singing the song that's And possibly bend you over look back and playing watch me "Akon!" [Chorus (2X):] [Akon:] Smack that all on the floor I feel you creeping, I can see it from my Smack that give me some more shadow Smack that 'till you get sore Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini Smack that oh-oh! Gallardo Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Upfront style ready to attack now TaeBo Pull in the parking lot slow with the lac down And possibly bend you over look back and Convicts got the whole thing packed now watch me Step in the club now and wardrobe intact now! I feel it down and cracked now (ooh) [Chorus] I see it dull and backed now I'm gonna call her, than I pull the mack down Eminem is rollin', d and em rollin' bo Money -

Rap Vocality and the Construction of Identity

RAP VOCALITY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY by Alyssa S. Woods A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Theory) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Nadine M. Hubbs, Chair Professor Marion A. Guck Professor Andrew W. Mead Assistant Professor Lori Brooks Assistant Professor Charles H. Garrett © Alyssa S. Woods __________________________________________ 2009 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of many people. I would like to thank my advisor, Nadine Hubbs, for guiding me through this process. Her support and mentorship has been invaluable. I would also like to thank my committee members; Charles Garrett, Lori Brooks, and particularly Marion Guck and Andrew Mead for supporting me throughout my entire doctoral degree. I would like to thank my colleagues at the University of Michigan for their friendship and encouragement, particularly Rene Daley, Daniel Stevens, Phil Duker, and Steve Reale. I would like to thank Lori Burns, Murray Dineen, Roxanne Prevost, and John Armstrong for their continued support throughout the years. I owe my sincerest gratitude to my friends who assisted with editorial comments: Karen Huang and Rajiv Bhola. I would also like to thank Lisa Miller for her assistance with musical examples. Thank you to my friends and family in Ottawa who have been a stronghold for me, both during my time in Michigan, as well as upon my return to Ottawa. And finally, I would like to thank my husband Rob for his patience, advice, and encouragement. I would not have completed this without you. -

Warren Egypt 1

EPISODE 278 WARREN EGYPT FRANKLIN 1 TRANSCRIPT [00:00:00] Hi, I'm stage and stage's Lin-Manuel Miranda, and you're listening to the Hamilcast. Gillian Pensavalle [00:00:18] Hello, everyone, welcome back to the Hamilcast, I am Gillian today I am joined, I'm so excited, Warren Egypt Franklin, hey my friend. Warren Egypt Franklin [00:00:27] This is a dream to be on here. I'm great. I am great. I'm so happy to do this. Gillian Pensavalle [00:00:34] It's a dream to be talking to you. So before we before we go any further, real quick, can you please tell me your pronouns? Warren Egypt Franklin [00:00:39] Yes. Is he/him Gillian Pensavalle [00:00:41] Great. Thank you so much. You are calling in from L.A. We're recording virtually. Of course you are. Lotfy of Jefferson on the Phillip tour of Hamilton. But everyone just heard you in the Elijah Malcomb episode freestyle Friday. You were you are real life best friends. You just told me Warren Egypt Franklin [00:00:57] We are the sons of Liberty. Me, Elijah and Desmond we like are really, really close in real life. So that's why it just translates so easy on stage because we really look out for each other real life. Those are my boys. My brothers. Yeah. Gillian Pensavalle [00:01:09] OK, so we have a lot to talk about. You are very busy. You are running off, you have something to to film. -

White Thugs & Black Bodies: a Comparison of the Portrayal Of

The Hilltop Review Volume 4 Issue 1 Spring Article 3 April 2010 White Thugs & Black Bodies: A Comparison of the Portrayal of African-American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel (2010) "White Thugs & Black Bodies: A Comparison of the Portrayal of African-American Women in Hip-Hop Videos," The Hilltop Review: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 1 1 WHITE THUGS & BLACK BODIES: A COMPARISON OF THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis Abstract. The continued appearance of African-American women as performers in rap and/or hip-hop videos has called attention to the male gaze1 and the ways in which young African-American women negotiate their sexuality. The most popular music videos of Caucasian and African-American hip-hop artists from 2003-2005 were analyzed and compared to determine the levels of sexism between the two cul- tures. With these videos, this study replicated a qualitative content analysis from an- other study that identified three prominent characteristics: (1) the level of sexism; (2) the presence of intimate touch and/the presence of alluring attire; and (3) which race portrayed women in a more sexist manner. -

STAR IS BORN, a (As Filmed 10-05-18)

A STAR IS BORN screenplay by Eric Roth and Bradley Cooper & Will Fetters based on the 1954 screenplay by Moss Hart and the 1976 screenplay by John Gregory Dunne & Joan Didion and Frank Pierson based on a story by William Wellman and Robert Carson This script is the confidential and proprietary property of Warner Bros. Pictures and no portion of it may be performed, distributed, reproduced, used, quoted or published without prior written permission. FINAL AS FILMED Release Date October 5, 2018 WARNER BROS. PICTURES INC. © 2018 4000 Warner Boulevard WARNER BROS. ENT. Burbank, California 91522 All Rights Reserved OVER BLACK We hear: A distant crowd becoming restless. A guitar being tuned. Buying time... The crowd’s cheers morph into “JACKSON... JACKSON... JACKSON.” FADE IN: INT. DOME TENT - BACKSTAGE - DUSK SILHOUETTE OF A MAN IN A HAT, head down. Spits... Then -- EMERGING FROM THE DARKNESS: JACKSON (JACK) MAINE (early 40s) pulls out a PRESCRIPTION PILL BOTTLE, dumps a FEW PILLS into his hand -- knocks them back -- drinks deeply from a GIN ON THE ROCKS, the alcohol spilling down his beard... the awaiting crowd just off in the b.g... A MALE ROADIE slaps him on the back. JACK All right, let’s do it. He walks onto -- INT. DOME TENT - MAIN STAGE - CONTINUOUS ACTION The crowd erupting. With a wave, he flings off his hat and wields his guitar, his RHYTHM GUITARIST now opposite him... And at once in tandem they unleash dueling guitars with the sheer force of rock ‘n’ roll -- an explosion of sound as the speakers scream his latest hit, “BLACK EYES” -- JACK (singing) ‘Black eyes open wide, It’s time to testify, There’s no room for lies, And everyone's waitin’ for you, And I'm gone, Sittin’ by the phone, And I'm all alone, By the wayside,’ The stage lights blaze from above as the song reaches its fever pitch.. -

Dangerfields

DANGERFIELDS Full Time Professional Disc Jockey Hire PO Box 467 Sherwood Qld 4075 (07) 3277 6534 Mob 0418 878 309 [email protected] You Tube - DangerfieldDJ LIBRARY: Text Only Version 1.Circle the artists and styles that you would like played at your function, then post it to us at the above address. Your Name:_____________________________ Date of Function: ______/______/______ Job Number: #___________(from our "Booking Confirmation" & "Deposit Received" letters) 2.This list has been compiled from both our archive library and our active collections. It represents only a small portion of the estimated 10,000 titles we have available. The more obscure artists may not be in our active collections and so not be available on every function. Therefore, please forward this list to us well in advance of your function to allow us time to compile your requests. (See note at end of listings.) CLASSICAL - String Quartet - Light Classical - Baroque e.g., Handel, Pachelbel, Hayden, Vivaldi, Mozart... (Over 250 CDs to choose from) JAZZ & SWING Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holliday, Edith Piaf, Harry Connick Jnr, Vince Jones, Grace Knight, Cherry Poppin Daddies, Billy Field/Bad Habits, George Benson, Sade, Frank Sinatra, Glenn Miller, Astrud Gilberto/Girl from Ipanema, Fabulous Baker Bros, Dave Brubeck, Dave Grusen, Oscar Peterson, Manhattan Transfer.... 40's BIG BAND ERA Bing Crosby, Glen Miller, Andrews Sisters, Vera Lynn, Marlene Dietrich, Edith Piaf, Woody Herman, Benny Goodman, Mills Brothers, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Carmen Miranda, Duke Ellington, The Ink Spots, Fats Waller, Artie Shaw, Acker Bilk... CORPORATE e.g., Tom Jones, Neil Diamond, Frank Sinatra, Van Morrison, Dean Martin, Perry Como, Buena Vista Social Club..