Motifs for Molecular Recognition Exploiting Hydrophobic Enclosure in Protein–Ligand Binding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organic Ligand Complexation Reactions On

Organic ligand complexation reactions on aluminium-bearing mineral surfaces studied via in-situ Multiple Internal Reflection Infrared Spectroscopy, adsorption experiments, and surface complexation modelling A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences 2010 Charalambos Assos School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................4 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................8 ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................10 DECLARATION.........................................................................................................11 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT....................................................................................12 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................13 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................38 CHAPTER 2 THE USE OF IR SPECTROSCOPY IN THE STUDY OF ORGANIC LIGAND SURFACE COMPLEXATION............................................40 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................40 METHODOLOGY ...........................................................................................................44 -

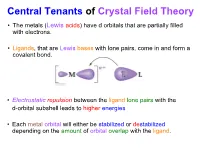

Crystal Field Theory (CFT)

Crystal Field Theory (CFT) The bonding of transition metal complexes can be explained by two approaches: crystal field theory and molecular orbital theory. Molecular orbital theory takes a covalent approach, and considers the overlap of d-orbitals with orbitals on the ligands to form molecular orbitals; this is not covered on this site. Crystal field theory takes the ionic approach and considers the ligands as point charges around a central metal positive ion, ignoring any covalent interactions. The negative charge on the ligands is repelled by electrons in the d-orbitals of the metal. The orientation of the d orbitals with respect to the ligands around the central metal ion is important, and can be used to explain why the five d-orbitals are not degenerate (= at the same energy). Whether the d orbitals point along or in between the cartesian axes determines how the orbitals are split into groups of different energies. Why is it required? The valence bond approach could not explain the Electronic spectra, Magnetic moments, Reaction mechanisms of the complexes. Assumptions of CFT: 1. The central Metal cation is surrounded by ligand which contain one or more lone pair of electrons. 2. The ionic ligand (F-, Cl- etc.) are regarded as point charges and neutral molecules (H2O, NH3 etc.) as point dipoles. 3. The electrons of ligand does not enter metal orbital. Thus there is no orbital overlap takes place. 4. The bonding between metal and ligand is purely electrostatic i.e. only ionic interaction. The approach taken uses classical potential energy equations that take into account the attractive and repulsive interactions between charged particles (that is, Coulomb's Law interactions). -

Interplay Between Gating and Block of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels

brain sciences Review Interplay between Gating and Block of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels Matthew B. Phillips 1,2, Aparna Nigam 1 and Jon W. Johnson 1,2,* 1 Department of Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA; [email protected] (M.B.P.); [email protected] (A.N.) 2 Center for Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-(412)-624-4295 Received: 27 October 2020; Accepted: 26 November 2020; Published: 1 December 2020 Abstract: Drugs that inhibit ion channel function by binding in the channel and preventing current flow, known as channel blockers, can be used as powerful tools for analysis of channel properties. Channel blockers are used to probe both the sophisticated structure and basic biophysical properties of ion channels. Gating, the mechanism that controls the opening and closing of ion channels, can be profoundly influenced by channel blocking drugs. Channel block and gating are reciprocally connected; gating controls access of channel blockers to their binding sites, and channel-blocking drugs can have profound and diverse effects on the rates of gating transitions and on the stability of channel open and closed states. This review synthesizes knowledge of the inherent intertwining of block and gating of excitatory ligand-gated ion channels, with a focus on the utility of channel blockers as analytic probes of ionotropic glutamate receptor channel function. Keywords: ligand-gated ion channel; channel block; channel gating; nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; ionotropic glutamate receptor; AMPA receptor; kainate receptor; NMDA receptor 1. Introduction Neuronal information processing depends on the distribution and properties of the ion channels found in neuronal membranes. -

Chapter 21 D-Metal Organometalloc Chemistry

Chapter 21 d-metal organometalloc chemistry Bonding Ligands Compounds Reactions Chapter 13 Organometallic Chemistry 13-1 Historical Background 13-2 Organic Ligands and Nomenclature 13-3 The 18-Electron Rule 13-4 Ligands in Organometallic Chemistry 13-5 Bonding Between Metal Atoms and Organic π Systems 13-6 Complexes Containing M-C, M=C, and M≡C Bonds 13-7 Spectral Analysis and Characterization of Organometallic Complexes “Inorganic Chemistry” Third Ed. Gary L. Miessler, Donald A. Tarr, 2004, Pearson Prentice Hall http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expedia 13-1 Historical Background Sandwich compounds Cluster compounds 13-1 Historical Background Other examples of organometallic compounds 13-1 Historical Background Organometallic Compound Organometallic chemistry is the study of chemical compounds containing bonds between carbon and a metal. Organometallic chemistry combines aspects of inorganic chemistry and organic chemistry. Organometallic compounds find practical use in stoichiometric and catalytically active compounds. Electron counting is key in understanding organometallic chemistry. The 18-electron rule is helpful in predicting the stabilities of organometallic compounds. Organometallic compounds which have 18 electrons (filled s, p, and d orbitals) are relatively stable. This suggests the compound is isolable, but it can result in the compound being inert. 13-1 Historical Background In attempt to synthesize fulvalene Produced an orange solid (ferrocene) Discovery of ferrocene began the era of modern organometallic chemistry. Staggered -

Searching Coordination Compounds

CAS ONLINEB Available on STN Internationalm The Scientific & Technical Information Network SEARCHING COORDINATION COMPOUNDS December 1986 Chemical Abstracts Service A Division of the American Chemical Society 2540 Olentangy River Road P.O. Box 3012 Columbus, OH 43210 Copyright O 1986 American Chemical Society Quoting or copying of material from this publication for educational purposes is encouraged. providing acknowledgment is made of the source of such material. SEARCHING COORDINATION COMPOUNDS prepared by Adrienne W. Kozlowski Professor of Chemistry Central Connecticut State University while on sabbatical leave as a Visiting Educator, Chemical Abstracts Service Table of Contents Topic PKEFACE ............................s.~........................ 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO SEARCHING IN CAS ONLINE ............... 1 What is Substructure Searching? ............................... 1 The Basic Commands .............................................. 2 CHAPTEK 2: INTKOOUCTION TO COORDINATION COPPOUNDS ................ 5 Definitions and Terminology ..................................... 5 Ligand Characteristics.......................................... 6 Metal Characteristics .................................... ... 8 CHAPTEK 3: STKUCTUKING AND REGISTKATION POLICIES FOR COORDINATION COMPOUNDS .............................................11 Policies for Structuring Coordination Compounds ................. Ligands .................................................... Ligand Structures........................................... Metal-Ligand -

Protein-Ligand Interactions from Molecular Recognition to Drug Design

P ) . .~ " r~- O Protein-Ligand Interactions From Molecular Recognition to Drug Design Edited by H.-J. Bohm and C. Schneider WILEY- VCH WILEY-VCH GmbH & Co. KGaA Contents Preface XI A Personal Foreword XIII List of Contributors XV List of Abbreviations XVII Prologue 1 David Brown 1 Prediction of Non-bonded Interactions in Drug Design 3 H.-J. Bohm 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Major Contributions to Protein-Ligand Interactions 4 1.3 Description of Scoring Functions for Receptor-Ligand Interactions 8 1.3.1 Force Field-based Methods 9 1.3.2 Empirical Scoring Functions 9 1.3.3 Knowledge-based Methods 11 1.4 Some Limitations of Current Scoring Functions 12 1.4.1 Influence of the Training Data 12 1.4.2 Molecular Size 13 1.4.3 Water Structure and Protonation State 13 1.5 Application of Scoring Functions in Virtual Screening and De Novo Design 14 1.5.1 Successful Identification of Novel Leads Through Virtual Screening 14 1.5.2 De novo Ligand Design with LUDI 25 1.6 Outlook 16 1.7 Acknowledgments 17 1.8 References 17 VI Contents 2 Introduction to Molecular Recognition Models 21 H.-J. Schneider 2.1 Introduction and Scope 21 2.2 Additivity of Pairwise Interactions - The Chelate Effect 22 2.3 Geometric Fitting: The Hole-size Concept 26 2.4 Di- and Polytopic Interactions: Change of Binding Mechanism with Different Fit 28 2.5 Deviations from the Lock-and-Key Principle 30 2.5.1 Strain in Host-Guest Complexes 30 2.5.2 Solvent Effects 30 2.5.3 Enthalpy/Entropy Variations 31 2.5.4 Loose Fit in Hydrophobically Driven Complex Formation 32 2.6 Conformational Pre-organization: Flexible vs. -

Molecular Recognition and Advances in Antibody Design and Antigenic Peptide Targeting

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Editorial Molecular Recognition and Advances in Antibody Design and Antigenic Peptide Targeting Gunnar Houen and Nicole Trier * Department of Neurology, Rigshospitalet Glostrup, Nordre Ringvej 57, 2600 Glostrup, Denmark; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 February 2020; Accepted: 15 February 2020; Published: 19 February 2020 Molecular recognition, the specific interaction between molecules by a combination of physical forces, has been a subject of scientific investigation for decades. The physical forces involve a combination of dipole-dipole interactions (van der Waals forces), hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions, and it is the optimal spatial combination of these interactions, that defines the specificity, i.e., the strength of the interaction, measured as an affinity constant, defined by the association and dissociation rate constants: Ka = kon/koff [1–3]. Specific interactions in living organisms are numerous, ranging from base pairing in DNA and RNA, protein folding, protein interactions and many more, constituting the basis of life [4–6]. Molecular recognition of foreign substances (self/non-self recognition) is the basis of immune defense against pathogens, spanning from less specific (promiscuous) MHC-peptide interactions to highly specific T cell (antigen) receptor (TCR) recognition of MHC-peptide complexes and from less specific IgM-antigen interactions to highly specific IgG-antigen interactions [7–9]. Through the study of the aforementioned specific interactions, scientists have learned to use natural molecules as reagents and have developed new reagents based on the same principles and physical forces. This issue of IJMS, entitled “Advances in Antibody Design and Antigenic Peptide Targeting” aims to give a status of the current “state-of-the-art” in specific molecular recognition. -

Complexation

FACULTY OF PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES, RAMAUNIVERSITY, KANPUR B.PHARM 3rd SEM PHYSICAL PHARMACEUTICS-I BP302T MR. PEEYUSH Assistant professor Rama university, kanpur Complexation Overview Classification Introduction Metal ion complexes Organic Complexes Inclusion Complexes Methods of Analysis Method of Continuous Variation PH Titration Distribution Method Solubility Method Spectroscopy Learning Objectives 1. Define the three classes of complexes with pharmaceutically relevant examples. 2. Describe chelates, their physically properties, and what differentiates them from organic molecular complexes. 3. Describe the types of forces that hold together organic molecular complexes with examples. 4. Describe the forces in polymer–drug complexes used for drug delivery. 5. Discuss the pharmaceutical applications of cyclodextrins. 6. Describe the methods of analysis of complexes and determine their stoichiometric ratios and stability constants. Classification Introduction Metal ion complexes Organic Complexes Inclusion Complexes INTRODUCTION Complexes are compounds that result from donor–acceptor mechanisms between two or more chemical species. Complexes can be divided broadly into three classes depending the type of the acceptor substance: 1. Metal ion complexes 2. Organic molecular complexes 3. Inclusion complexes Intermolecular forces involved in the formation of complexes: 1. Van der Waals forces. 2. Hydrogen bonds (important in molecular complexes). 3. Coordinate covalence (important in metal complexes). 4. Charge transfer. 5. Hydrophobic interaction. Introduction Types of Complexes Metal Ion Complexes A. Inorganic type B. Chelates C. Olefin type D. Aromatic type II. Organic Molecular Complexes A. Quinhydrone type B. Picric acid type C. Caffeine and other drug complexes D. Polymer type III. Inclusion Compounds A. Channel lattice type B. Layer type C. Clathrates D. Monomolecular type E. -

Physical Organic Chemistry

PHYSICAL ORGANIC CHEMISTRY Yu-Tai Tao (陶雨台) Tel: (02)27898580 E-mail: [email protected] Website:http://www.sinica.edu.tw/~ytt Textbook: “Perspective on Structure and Mechanism in Organic Chemistry” by F. A. Corroll, 1998, Brooks/Cole Publishing Company References: 1. “Modern Physical Organic Chemistry” by E. V. Anslyn and D. A. Dougherty, 2005, University Science Books. Grading: One midterm (45%) one final exam (45%) and 4 quizzes (10%) homeworks Chap.1 Review of Concepts in Organic Chemistry § Quantum number and atomic orbitals Atomic orbital wavefunctions are associated with four quantum numbers: principle q. n. (n=1,2,3), azimuthal q.n. (m= 0,1,2,3 or s,p,d,f,..magnetic q. n. (for p, -1, 0, 1; for d, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2. electron spin q. n. =1/2, -1/2. § Molecular dimensions Atomic radius ionic radius, ri:size of electron cloud around an ion. covalent radius, rc:half of the distance between two atoms of same element bond to each other. van der Waal radius, rvdw:the effective size of atomic cloud around a covalently bonded atoms. - Cl Cl2 CH3Cl Bond length measures the distance between nucleus (or the local centers of electron density). Bond angle measures the angle between lines connecting different nucleus. Molecular volume and surface area can be the sum of atomic volume (or group volume) and surface area. Principle of additivity (group increment) Physical basis of additivity law: the forces between atoms in the same molecule or different molecules are very “short range”. Theoretical determination of molecular size:depending on the boundary condition. -

High Spin Or Low Spin?

Central Tenants of Crystal Field Theory • The metals (Lewis acids) have d orbitals that are partially filled with electrons. • Ligands, that are Lewis bases with lone pairs, come in and form a covalent bond. • Electrostatic repulsion between the ligand lone pairs with the d-orbital subshell leads to higher energies • Each metal orbital will either be stabilized or destabilized depending on the amount of orbital overlap with the ligand. CFT (Octahedron) (dz2, dx2-y2) Orbitals point directly at ligands eg stronger repulsion dx2y2 E dz2 higher energy (dxy, dyz, dxz) Orbitals point between ligands t2g dxy dyz dxz weaker repulsion lower energy Energy Levels of d-Orbitals in an Octahedron • crystal field splitting energy = • The size of is determined by; metal (oxidation state; row of metal, for 5d > 4d >> 3d) ligand (spectrochemical series) Spectrochemical Series eg eg t2g t2g 3+ [Cr(H2O)6] Greater I < Br < Cl < F < OH < H2O < NH3 < en < NO2 < CN < CO Small Δ Large Δ Weak Field Strong Field Weak M-L interactions Strong M-L interactions How Do the Electrons Go In? • Hund’s rule: one electron each in lowest energy orbitals first • what happens from d4 to d7? d6 Crystal Field Spin Pairing Splitting vs. Δ P High Spin vs. Low Spin Co3+ (d6) High Spin Low Spin Δ < P Δ > P High Spin vs. Low Spin Configurations High Spin vs. Low Spin Configurations high spin low spin d4 3d metal 3d metal weak field strong field ligand d5 ligand 4d & 5d 6 d always d7 What About Other Geometries? linear (CN = 2) z y x tetrahedral (CN = 4) z y x square planar (CN = 4) z how do the electrons on the d orbitals y interact with the ligands in these cases? x Tetrahedral vs. -

Intriguing Role of Water in Protein-Ligand Binding Studied by Neutron Crystallography on Trypsin Complexes

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05769-2 OPEN Intriguing role of water in protein-ligand binding studied by neutron crystallography on trypsin complexes Johannes Schiebel1,2, Roberto Gaspari2, Tobias Wulsdorf1, Khang Ngo1, Christian Sohn1, Tobias E. Schrader 3, Andrea Cavalli2, Andreas Ostermann 4, Andreas Heine1 & Gerhard Klebe1 fi 1234567890():,; Hydrogen bonds are key interactions determining protein-ligand binding af nity and therefore fundamental to any biological process. Unfortunately, explicit structural information about hydrogen positions and thus H-bonds in protein-ligand complexes is extremely rare and similarly the important role of water during binding remains poorly understood. Here, we report on neutron structures of trypsin determined at very high resolutions ≤1.5 Å in uncomplexed and inhibited state complemented by X-ray and thermodynamic data and computer simulations. Our structures show the precise geometry of H-bonds between protein and the inhibitors N-amidinopiperidine and benzamidine along with the dynamics of the residual solvation pattern. Prior to binding, the ligand-free binding pocket is occupied by water molecules characterized by a paucity of H-bonds and high mobility resulting in an imperfect hydration of the critical residue Asp189. This phenomenon likely constitutes a key factor fueling ligand binding via water displacement and helps improving our current view on water influencing protein–ligand recognition. 1 Institut für Pharmazeutische Chemie, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marbacher Weg 6, 35032 Marburg, Germany. 2 Computational Sciences, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Via Morego 30, 16163 Genova, Italy. 3 Jülich Centre for Neutron Science at Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Lichtenbergstraße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany. 4 Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum, Technische Universität München, Lichtenbergstraße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany. -

Introduction to the Molecular Recognition and Self-Assembly Special Feature

SPECIAL FEATURE: INTRODUCTORY PERSPECTIVE Introduction to the Molecular Recognition and Self-Assembly Special Feature Julius Rebek, Jr.1 The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037 olecular recognition is a ist. On mixing, these 2 capsules form a and departures for possible future mature branch of chemical hybrid, which is more stable than ei- applications. science, and why shouldn’t ther original capsule. The formation of A switching device is involved in a it be? Decades of studies in the hybrid provides places for guests calyx[6]arene that offers 2 separate Mphysical organic chemistry have defined that could not otherwise be accommo- binding sites in the work of Coquie`re et and evaluated the weak intermolecular dated. As in certain schools of archi- al. (6), ‘‘Multipoint molecular recogni- forces involved when 2 molecules en- tecture, reversible encapsulation is less tion within a calix[6]arene funnel com- counter each other. Every bimolecular about the mechanical boundaries of plex.’’ The conformational mobility of reaction, whether it occurs in the gas the walls than it is about the spaces the system allows 3 imidazole arms to phase, dilute solution, or an enzyme’s they define. chelate zinc ions, while 3 aniline nitro- interior, begins with a recognition event. Encapsulation of multiple groups of gens converge to provide a binding site It is an apt time to explore recognition small molecules is the theme of the arti- for a single proton. The space in the in a larger context, that of multicompo- cle by Yamauchi et al.