Status Report on the Agulhas Plain Study Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abnormal Waves on the South East Coast of South Africa

ABNORMAL WAVES ON THE SOUTH EAST COAST OF SOUTH AFRICA by J. K. M allo ry Master M ariner, Captain, S. A. Navy (Rtd.), Professor of Oceanography, University of Cape Town Much has been said and written recently about the abnormal waves which have been experienced over the years along the eastern seaboard of South Africa. Many theories have been put forward as to the probable causes of these waves which have incurred considerable damage to vessels when steaming in a southwesterly direction down the east coast between Durnford Point and Great Fish Point. It would therefore be of interest to examine the details concerning the individual occurrences as far as they are known. Unfortunately it is not always possible to obtain full details after a period of time has elapsed since the wave was reported, hence in some instances the case histories are incomplete. It is safe to say that many other ships must have experienced abnormal waves off the South African coast between Durnford Point and Cape Recife, but because the speed of the vessel at the time had been suitably reduced, the ship sustained no damage and hence there was no specific reason for reporting such an occurrence other than as a matter of interest. This is unfortunate because so much more could have been learnt about these phenomena if more specific reports were available, especially if they were to include details on wind and waves, meteorological data, soundings, ship’s course and speed. A list of eleven known cases of vessels either having reported encountering abnormal wave conditions or having foundered as a result of storm waves is given in Appendix A. -

Cape-Agulhas-WC033 2020 IDP Amendment

REVIEW AND AMENDMENTS TO THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/21 CAPE AGULHAS MUNICIPALITY REVIEW AND AMENDMENTS TO THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/21 29 My 2020 Together for excellence Saam vir uitnemendheid Sisonke siyagqwesa 1 | P a g e REVIEW AND AMENDMENTS TO THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/21 SECTIONS THAT ARE AMENDED AND UPDATED FOREWORD BY THE EXECUTIVE MAYOR (UPDATED)............................................................................ 4 FOREWORD BY THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER (UPDATED) ..................................................................... 5 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 INTRODUCTION TO CAPE AGULHAS MUNICIPALITY (UPDATED) ......................................... 7 1.2 THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN AND PROCESS ......................................................... 8 1.2.4 PROCESS PLAN AND SCHEDULE OF KEY DEADLINES (AMENDMENT) ........................... 8 1.3 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION STRUCTURES, PROCESSES AND OUTCOMES .................................. 9 1.3.3 MANAGEMENT STRATEGIC WORKSHOP (UPDATED) .................................................... 10 2. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL STRATEGY ALIGNMENT ................................. 11 2.2.2 WESTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL PERSPECTIVE (AMENDED) ............................................. 11 3 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS............................................................................................................... -

Private Governance of Protected Areas in Africa: Case Studies, Lessons Learnt and Conditions of Success

Program on African Protected Areas & Conservation (PAPACO) PAPACO study 19 Private governance of protected areas in Africa: case studies, lessons learnt and conditions of success @B. Chataigner Sue Stolton and Nigel Dudley Equilibrium Research & IIED Equilibrium Research offers practical solutions to conservation challenges, from concept, to implementation, to evaluation of impact. With partners ranging from local communities to UN agencies across the world, we explore and develop approaches to natural resource management that balance the needs of nature and people. We see biodiversity conservation as an ethical necessity, which can also support human wellbeing. We run our own portfolio of projects and offer personalised consultancy. Prepared for: IIED under contract to IUCN EARO Reproduction: This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission, provided acknowledgement to the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose without permission in writing from Equilibrium Research. Citation: Stolton, S and N Dudley (2015). Private governance of protected areas in Africa: Cases studies, lessons learnt and conditions of success. Bristol, UK, Equilibrium Research and London, UK, IIED Cover: Private conservancies in Namibia and Kenya © Equilibrium Research Contact: Equilibrium Research, 47 The Quays Cumberland Road, Spike Island Bristol, BS1 6UQ, UK Telephone: +44 [0]117-925-5393 www.equilibriumconsultants.com Page | 2 Contents 1. Executive summary -

Know Your National Parks

KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS 1 KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS Our Parks, Our Heritage Table of contents Minister’s Foreword 4 CEO’s Foreword 5 Northern Region 8 Marakele National Park 8 Golden Gate Highlands National Park 10 Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage site 11 Arid Region 12 Augrabies Falls National Park 12 Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park 13 Mokala National Park 14 Namaqua National Park 15 /Ai/Ais-Richtersveld Transfrontier Park 16 Cape Region 18 Table Mountain National Park 18 Bontebok National Park 19 Agulhas National Park 20 West Coast National Park 21 Tankwa-Karoo National Park 22 Frontier Region 23 Addo Elephant National Park 23 Karoo National Park 24 DID YOU Camdeboo National Park 25 KNOW? Mountain Zebra National Park 26 Marakele National Park is Garden Route National Park 27 found in the heart of Waterberg Mountains.The name Marakele Kruger National Park 28 is a Tswana name, which Vision means a ‘place of sanctuary’. A sustainable National Park System connecting society Fun and games 29 About SA National Parks Week 31 Mission To develop, expand, manage and promote a system of sustainable national parks that represent biodiversity and heritage assets, through innovation and best practice for the just and equitable benefit of current and future generation. 2 3 KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS Minister’s Foreword CEO’s Foreword We are blessed to live in a country like ours, which has areas by all should be encouraged through a variety of The staging of SA National Parks Week first took place been hailed as a miracle in respect of our transition to a programmes. -

The Ecology of Large Herbivores Native to the Coastal Lowlands of the Fynbos Biome in the Western Cape, South Africa

The ecology of large herbivores native to the coastal lowlands of the Fynbos Biome in the Western Cape, South Africa by Frans Gustav Theodor Radloff Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Science (Botany) at Stellenbosh University Promoter: Prof. L. Mucina Co-Promoter: Prof. W. J. Bond December 2008 DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 24 November 2008 Copyright © 2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii ABSTRACT The south-western Cape is a unique region of southern Africa with regards to generally low soil nutrient status, winter rainfall and unusually species-rich temperate vegetation. This region supported a diverse large herbivore (> 20 kg) assemblage at the time of permanent European settlement (1652). The lowlands to the west and east of the Kogelberg supported populations of African elephant, black rhino, hippopotamus, eland, Cape mountain and plain zebra, ostrich, red hartebeest, and grey rhebuck. The eastern lowlands also supported three additional ruminant grazer species - the African buffalo, bontebok, and blue antelope. The fate of these herbivores changed rapidly after European settlement. Today the few remaining species are restricted to a few reserves scattered across the lowlands. This is, however, changing with a rapid growth in the wildlife industry that is accompanied by the reintroduction of wild animals into endangered and fragmented lowland areas. -

AGULHAS PARK Ebulletin December 2010, Volume 9 Sanparks 13 – 17 Sept 2010 Park Week

AGULHAS PARK eBULLETIN December 2010, Volume 9 SANParks www.agulhas.org.za 13 – 17 Sept 2010 Park Week DECEMBER eBULLETIN LIGHTHOUSE PRECINCT DEVELOPMENT Should you wish to be added to our email list please send an email The Lighthouse Precinct Development is in an with “SUBSCRIBE” on the subject line to [email protected] advanced stage and will be completed in two separate phases. Phase one is terrain development, i.e. civil works and provision of services. This phase also entails moving the Warmest wishes for a navigation component of Transnet National Ports Authority and the construction of the happy holiday season relative buildings. Phase two is the construction of the buildings. and a wonderful new The restoration planning of the Lighthouse itself, managed by Transnet, is on course and year from all of us at any further developments in this regard will be aired in the future Newsletters. the Agulhas National FAUNA Park! SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SOUTHERNMOST TIP OF AFRICA S34˚49’59” E20˚00’12” The navigators of the 1400s to the 1700s who discovered the sea route around the southernmost tip, observed the sun at noon when it passed the meridian, and found that the magnetic compass pointed to true north. Today it points some 24 degrees west of true north. The marine flora includes at least nine seaweed species of the Cool Perlemoen Abalone Haliotis midae - Mbulelo Dopolo, Temperate Southwest Coast province that are common between Cape Point and Cape Agulhas, but rare or absent just east, from the De Marine Program Manager, Cape Research Centre: Scientific Services Hoop Nature Reserve. -

Conservation Management in Agulhas National Park: Challenges & Successes a PLACE of CONTINENTAL SIGNIFICANCE…

Conservation Management in Agulhas National Park: Challenges & Successes A PLACE OF CONTINENTAL SIGNIFICANCE… 20⁰00’E 34⁰ 50’ S to be celebrated, a showcase of all we are and all we can achieve SOUTHERNMOST TIP OF AFRICA S34˚49’59” E20˚00’12” ↑ On 14 September 1998 SANParks acquired a 4 ha portion of land at the southernmost tip of the African continent to establish a national park. Reason for establishment Declared in 1999 (GN 1135 in GG 20476) dated 23 September 1999. The key intention of founding the park was to protect the following 4 aspects: Lowland fynbos with A wide variety of wet- Geographic location Rich cultural heritage four vegetation units lands(freshwater of the Southernmost (From Stone-age, San, Khoi with high conservation springs,rivers,estuaries Tip of Africa herders, Shipwrecks, status: ,floodplains,lakes, vleis (To conserve and European settlement, Fishermen, agriculture, Central rûens shale and pans) The ecological maintain the spirit of flower farming, salt mining renoster-veld (critically functioning of the wetlands and place of the endangered); other fresh water systems on southernmost tip of until today) Elim ferricrete fynbos the Agulhas plain is critically Africa and develop its (endangered) dependent on water quality and tourism potential) Agulhas sand fynbos quantity of interlinked pans, wetlands, seasonal streams, (vulnerable) flow and interchanges that Cape inland salt pans occur under natural conditions. (vulnerable The ANP started out with the following huge establishment challenges: • Staff capacity insufficient -

Responsible Tourism in Sanparks

Responsible tourism in SANParks Join our community today www.wildcard.co.za | 0861 go WiLD (46 9453) SANPARKS coNNectiNg to S ociety The road ahead THE JOURNEY CONTINUES ourism and our National Parks go right back to the inception of the Parks. It can even be said that one of the reasons that the National Parks still exist is because of tourism. How could that be, you may ask. Contents TWell, there are two key reasons. Firstly, if people were not part of the National Park ‘ecosystem’, they would not have formed the strong bonds that they have with our National Parks – emotional bonds that echo those between parents and children. 04 Like bringing up children, managing the Parks is a long and unpredictable Way, Way back process that does not come with a fail-safe manual. You make mistakes. You learn lessons. You adapt. And so you make progress on your journey through life ... one step at a time. 06 This adaptive process has, over the lifetime of the National Parks, shaped the steep inclines decisions taken by those entrusted with the running of the Parks. Some decisions have been good. Others, with the benefit of hindsight, not so good. However, in the main, our National Parks have become an international success story, an example of how a system can adapt to changes in society and its demands. 08 Remaining relevant and evolving with society is the key to the Parks’ future exploring neW success. That means we as the current custodians need to keep adapting in order horizons to ensure the survival of our precious National Parks. -

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps DRAFT May 2009 South African National Biodiversity Institute Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Contents List of tables .............................................................................................................................. vii List of figures............................................................................................................................. vii 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 2 Criteria for identifying threatened ecosystems............................................................... 10 3 Summary of listed ecosystems ........................................................................................ 12 4 Descriptions and individual maps of threatened ecosystems ...................................... 14 4.1 Explanation of descriptions ........................................................................................................ 14 4.2 Listed threatened ecosystems ................................................................................................... 16 4.2.1 Critically Endangered (CR) ................................................................................................................ 16 1. Atlantis Sand Fynbos (FFd 4) .......................................................................................................................... 16 2. Blesbokspruit Highveld Grassland -

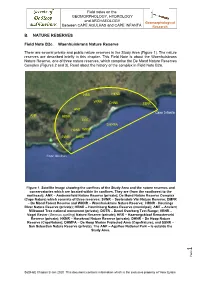

B. NATURE RESERVES Field Note B2c

Field notes on the GEOMORPHOLOGY, HYDROLOGY and ARCHAEOLOGY Geomorphological Between CAPE AGULHAS and CAPE INFANTA Research B. NATURE RESERVES Field Note B2c. Waenhuiskrans Nature Reserve There are several private and public nature reserves in the Study Area (Figure 1). The nature reserves are described briefly in this chapter. This Field Note is about the Waenhuiskrans Nature Reserve, one of three nature reserves, which comprise the De Mond Nature Reserves Complex (Figures 2 and 3). Read about the history of the complex in Field Note B2a. HRR HKNR VRNR DHNR SSNR AMT Cape Infanta ANP HBNR DOT R DHMPA HRNR WKNR SVNR DMFR ANR Cape Agulhas Figure 1. Satellite image showing the confines of the Study Area and the nature reserves and conservatories which are located within its confines. They are (from the southwest to the northeast): ANR – Andrewsfield Nature Reserve (private); De Mond Nature Reserve Complex (Cape Nature) which consists of three reserves: SVNR – Soetendals Vlei Nature Reserve; DMFR – De Mond Forest Reserve and WKNR – Waenhuiskrans Nature Reserve; HRNR - Heunings River Nature Reserve (private); HBNR – Heuninberg Nature Reserve (municipal); AMT – Ancient Milkwood Tree national monument (private); DOTR – Denel Overberg Test Range; VRNR – Vogel Revier (German spelling) Nature Reserve (private); HRR – Haarwegskloof Renosterveld Reserve (private); HKNR – Hasekraal Nature Reserve (private); DHNR – De Hoop Nature Reserve (CapeNature); DHMPA – De Hoop Marine Protected Area (CapeNature); and SSNR – San Sebastian Nature Reserve (private). The ANP – Agulhas National Park – is outside the Study Area. 1 Page SoDHaE Chapter B Jan 2020 This document contains information which is the exclusive property of Yoav Eytam Field notes on the GEOMORPHOLOGY, HYDROLOGY and ARCHAEOLOGY Geomorphological Between CAPE AGULHAS and CAPE INFANTA Research The De Mond Nature Reserve Complex is located between Struis Bay in the southwest and Arniston in the northeast (Figure 2). -

SA National Parks Tariffs 01 November 2020

SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL PARKS TARIFFS 1 NOVEMBER 2020 to 31 OCTOBER 2021 All Prices VAT inclusive and all tariffs in South African Rand Tariffs subject to alteration without advance notice Errors and omissions excepted ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- GENERAL INFORMATION SANParks have implemented a Community Fund charge on all reservations (overnight and activity products) from 1 June 2012. This will be used to fund projects that support surrounding communities in bettering their livelihoods. For more information please view our website on www.sanparks.org All accommodation, ablution and kitchen facilities are serviced by cleaning staff on a daily basis unless specifically indicated otherwise. Several parks and rest-camps have retail facilities and restaurants. Tariffs do not include meals unless specifically indicated otherwise. Vehicle fuel is available in several parks (or is available on the park periphery) and in the main rest camps in Kruger and Kgalagadi. Bedding is supplied in all accommodation unless specifically indicated otherwise. Cooking utensils and refrigeration are provided in most accommodation units. Exceptions will be indicated while booking Additional Person Supplements are applicable to those units where number of beds exceeds the base occupancy, if these beds are occupied Adult rates apply to persons 12 years and older. Child rates apply to persons aged 2-11 years. Infants under 2 years gratis Nationals of SADC countries that are part of a transfrontier agreement or treaty will have the same benefits as South African residents for park-specific daily conservation fee charges. For example, a Mozambique and Zimbabwe national visiting Kruger or a Botswana national visiting Kgalagadi, will pay a daily conservation fee equal to what South African nationals pay (instead of the fee other SADC nationals pay). -

Tariff and Membership Details

WILD CARD PROGRAMME TARIFF AND MEMBERSHIP DETAILS July 2011 MEMBERSHIP CATEGORIES INDIVIDUAL COUPLE FAMILY (1 PAX) (2 PAX) (MAX 7 PAX) ALL PARKS CLUSTER Access to more than 80 Parks and Reserves around Southern Africa Includes access to all Parks and Reserves, which are included in the R 340 R 560 R 700 SANParks, Msinsi, EKZNWildlife, Cape Nature and Swazi Clusters SANPARKS CLUSTER R 325 R 535 R 640 Access to all 21 of SANParks National Parks in South Africa MSINSI CLUSTER Access to all 6 of Msinsi’s Resorts and Reserves near Durban and Pietermaritzburg R 290 R 475 R 565 EKZNWILDLIFE CLUSTER Access to 24 of KZN Wildlife’s Parks and Reserves in KwaZulu-Natal R 275 R 450 R 535 CAPENATURE CLUSTER Access to 24 of Cape Nature’s Parks and Reserves in the Western Cape R 305 R 505 R 600 MEMBERSHIP CLUSTER SWAZILAND’S BIG GAME PARKS CLUSTER Access to Big Game Parks of Swaziland’s 3 Parks in Swaziland R 270 R 435 R 525 INTERNATIONAL ALL PARKS CLUSTER Access to more than 80 Parks and Reserves around Southern Africa Includes access to all Parks and Reserves, which are included in the R 1,310 R 2,195 R 2,620 SANParks, Msinsi, EKZNWildlife, Cape Nature and Swazi Clusters MEMBERSHIP CATEGORY MEMBERSHIP RULES • Maximum of 1 Person • Any 1 person of any age INDIVIDUAL MEMBERSHIP • Membership is non-transferable, thus person cannot be changed during the course of a membership cycle of 1 year • Maximum of 2 Persons • Can be any two persons • Maximum of 2 Adults, or 1 Adult and 1 Child • COUPLE MEMBERSHIP A Child is anyone under the age of 18 years of age • Membership is non-transferable, thus main cardholder cannot be changed.