1 Jack L. Jacobs Personal Information: Office Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, launch May 1 with an event at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York completion of this landmark project in December 2021. Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed rare or unique books have now been digitized and put Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah online for researchers, teachers, and students around the photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article world to read. The next important step in developing (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to European Jewish Life. The museum will launch early explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures 2021. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, is currently being tested. Through Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us the art of storytelling the museum will provide the online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). historical context for the archive’s vast array of original documents, books, and other artifacts, with some materials being translated to English for the first time. -

Read the Conference Program

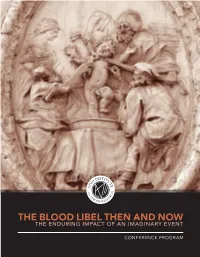

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English

MONDAY The Rise of Yiddish Scholarship JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English As Jewish activists sought to build a modern, secular culture in the late nineteenth century they stressed the need to conduct research in and about Yiddish, the traditionally denigrated vernacular of European Jewry. By documenting and developing Yiddish and its culture, they hoped to win respect for the language and rights for its speakers as a national minority group. The Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute], known by its acronym YIVO, was founded in 1925 as the first organization dedicated to Yiddish scholarship. Throughout its history, YIVO balanced its mission both to pursue academic research and to respond to the needs of the folk, the masses of ordinary Yiddish- speaking Jews. This talk will explore the origins of Yiddish scholarship and why YIVO’s work was seen as crucial to constructing a modern Jewish identity in the Diaspora. Cecile Kuznitz is Associate Professor of Jewish history and Director of Jewish Studies at Bard College. She received her Ph.D. in modern Jewish history from Stanford University and previously taught at Georgetown University. She has held fellowships at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In summer 2013 she was a Visiting Scholar at Vilnius University. She is the author of several articles on the history of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Jewish community of Vilna, and the field of Yiddish Studies. English-Language Bibliography of Recent Works on Yiddish Studies CECILE KUZNITZ Baker, Zachary M. -

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed Until

Prepared for: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed until: February 14, 2007 at 10 AM EST BACKGROUND TO THE SITUATION OF JEWS IN THE NETHERLANDS UNDER NAZI OCCUPATION AND OF THE FAMILY OF OTTO FRANK By: David Engel Greenberg Professor of Holocaust Studies New York University Understanding the situation of Jews in the Netherlands under Nazi occupation, like understanding any aspect of the Holocaust, requires suspension of hindsight. No one could know in 1933, 1938, or even early 1941 that the Nazi regime would soon embark upon a systematic program aimed at killing each and every Jewish man, woman, and child within its reach. The statement is true of top German officials no less than it is of the Jewish and non-Jewish civilian populations of the twenty countries within the Nazi orbit and of the governments and peoples of the Allied and neutral countries. Although it is tempting to look back upon the history of Nazi anti-Jewish utterances and measures and to detect in them an ostensible inner logic leading inexorably to mass murder, the consensus among historians today is that when the Nazi regime came to power in January 1933 it had no clear idea how the so-called Jewish problem might best be solved. It knew only that, from its perspective, Jews presented a problem that would need to be solved sooner or later, but finding a long-term solution was initially not one of the regime's most immediate priorities. Between 1933-41 various Nazi agencies proposed different schemes for dealing with Jews. -

Polish Jewry: a Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein

Polish Jewry: A Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein © YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 2013 The old castle and the Maharsha synagogue in Ostrog, connected by an underground passage. Built in the 17th century, the synagogue was named after Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer Eidels (1555 – 1631), author of the work Hidushei Maharsha. In 1795 the Jews of Ostrog escaped death by hiding in the synagogue during a military attack. To celebrate their survival, the community observed a special Purim each year, on the 7th of Tamuz, and read a scroll or Megillah which told the story of this miracle. Photograph by Alter Kacyzne. YIVO Archives. Courtesy of the Forward Association. A Haven from Persecution YIVO’s dedication to the study of the history of Jews in Poland reflects the importance of Polish Jewry in the Jewish world over a period of one thou- sand years, from medieval times until the 20th century. In early medieval Europe, Jewish communities flourished across a wide swath of Europe, from the Mediterranean lands and the Iberian Peninsu- la to France, England and Germany. But beginning with the first crusade in 1096 and continuing through the 15th century, the center of Jewish life steadily moved eastward to escape persecutions, massacres, and expulsions. A wave of forced expulsions brought an end to the Jewish presence in West- ern Europe for long periods of time. In their quest to find safe haven from persecutions, Jews began to settle in Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, and parts of Ukraine, and were able to form new communities there during the 12th through 14th centuries. -

Proposal for the Registry of the Latin American And

1 MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER Collection of the Center of Documentation and Investigation of the Ashkenazi Community in Mexico (16th to 20th Century) (Mexico) Ref N° 2008-11 PART A 1.- SUMMARY The Center of Documentation and Investigation of the Ashkenazi Community of Mexico keeps, preserves and disseminates the Ashkenazi culture, the culture of the Jewish people that was on the verge of disappearing during the Nazi era. It also safeguards the historic memory of the Jewish minority in Mexico that arrived from Central and Eastern Europe. Introduction. From the end of the 19th century the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe decided to emigrate towards America so as to find better living conditions. At that moment, large groups of Jews cut their ties to the lands in which they had developed a way of life, a language (Yiddish) and a manner of being: the Ashkenazi. Their former life ended violently and forever. At first, because of the pogroms unleashed by the Cossacks and Ukrainians, at the dawn of the 20th century by the First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution, but mostly from the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 30s that led to the loss of six million people and thus to the disappearance of the Jewish communities of Central and Eastern Europe. At that moment, the Ashkenazi culture was threatened with extinction once the study centers and places for creating culture were wiped out during the Second World War. The few survivors of the Holocaust bore upon their shoulders the difficult task of rescuing themselves and their Jewish identity that had been so heavily menaced during the six years of war, the ghettos and the concentration and extermination camps. -

Sephardic Family History Research Guide

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute Updated September 2008 Sephardic Family History Research Guide Sephardim Spanish Jews, who had lived on the Iberian Peninsula since 6 B.C.E, began to call themselves Sephardim during the early Middle Ages. After the expulsions from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1497), Jews fled to numerous places within Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and the New World. The word Sephardim came to refer to the Jews of these countries whose origins still remained in Spain or Portugal and who spoke Ladino and other Spanish regional dialects. Sephardic Genealogy Since the Sephardic world is so diverse and widespread, it is difficult to make generalizations about Sephardic genealogy. The sources, methods, and results of genealogical research on a family in Amsterdam, for example, differ greatly from research on a family in Aleppo or Salonika. However, there are several common characteristics: • Sephardic family names are much older than most Ashkenazi names. With Hebraic, Aramaic, Spanish or Arabic roots, Sephardic surnames are often traceable to the 11th century and even earlier. • In Sephardic naming customs, children can be named for both the living and the dead. Often, the firstborn son is named after the paternal grandfather, and the firstborn daughter is named after the paternal grandmother, so that given names may appear in every other generation. Resources at the Center for Jewish History General References Etsi (www.geocities.com/EnchantedForest/1321): journal of Sephardic genealogy (French/English) Genealogy Institute Faiguenboim, Guilherme, Paulo Valadares, and Anna Campagnano. Dicionário Sefaradi de Sobrenomes. (Sao Paulo, Fraiha, 2003) Genealogy Institute CS 3010 .F35 2003 Gandhi, Maneka. -

Jewish Labor Bund's

THE STARS BEAR WITNESS: THE JEWISH LABOR BUND 1897-2017 112020 cubs בונד ∞≥± — A 120TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF THE FOUNDING OF THE JEWISH LABOR BUND October 22, 2017 YIVO Institute for Jewish Research at the Center for Jewish History Sponsors YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Jonathan Brent, Executive Director Workmen’s Circle, Ann Toback, Executive Director Media Sponsor Jewish Currents Executive Committee Irena Klepisz, Moishe Rosenfeld, Alex Weiser Ad Hoc Committee Rochelle Diogenes, Adi Diner, Francine Dunkel, Mimi Erlich Nelly Furman, Abe Goldwasser, Ettie Goldwasser, Deborah Grace Rosenstein Leo Greenbaum, Jack Jacobs, Rita Meed, Zalmen Mlotek Elliot Palevsky, Irene Kronhill Pletka, Fay Rosenfeld Gabriel Ross, Daniel Soyer, Vivian Kahan Weston Editors Irena Klepisz and Daniel Soyer Typography and Book Design Yankl Salant with invaluable sources and assistance from Cara Beckenstein, Hakan Blomqvist, Hinde Ena Burstin, Mimi Erlich, Gwen Fogel Nelly Furman, Bernard Flam, Jerry Glickson, Abe Goldwasser Ettie Goldwasser, Leo Greenbaum, Avi Hoffman, Jack Jacobs, Magdelana Micinski Ruth Mlotek, Freydi Mrocki, Eugene Orenstein, Eddy Portnoy, Moishe Rosenfeld George Rothe, Paula Sawicka, David Slucki, Alex Weiser, Vivian Kahan Weston Marvin Zuckerman, Michael Zylberman, Reyzl Zylberman and the following YIVO publications: The Story of the Jewish Labor Bund 1897-1997: A Centennial Exhibition Here and Now: The Vision of the Jewish Labor Bund in Interwar Poland Program Editor Finance Committee Nelly Furman Adi Diner and Abe Goldwasser -

The Status of Judeo-Spanish in a Diachronic and Synchronic Perspective Includes Six Translated Romances Plus Sample Texts of Biblical Literature and Modern Press

The status of Judeo-Spanish in a diachronic and synchronic perspective Includes six translated Romances plus sample texts of biblical literature and modern press Lester Fernandez Vicet Master thesis in Semitic Linguistics with Hebrew (60 credits) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo May 2016 Abstract. The speech of the Sephardic Jews have been defined as both language and dialect, depending always on the standpoint of the analyzer, but is it a language on its own right or is it “just a dialect”? What is, then, the difference between both concepts? In the case Judeo-Spanish could be considered a language, what are the criteria taken into account in the classification? In an attempt to answer these questions I will provide facts on the origin of both terms, their modern and politicized use as well as on the historical vicissitudes of Judeo-Spanish and its speakers. Their literature, both laic and religious, is covered with an emphasis on the most researched and relevant genres, namely: the biblical Sephardic translations, the Romancero and the modern press of the 19th Century. A descriptive presentation of Judeo-Spanish main grammatical features precedes the last chapter, where both the diagnosis of Judeo-Spanish in the 20th Century, and its prognosis for the 21st, are given with the aim of determine its present state. Acknowledgements The conception and execution of the present work would have been impossible without the help and support of the persons that were, directly or indirectly, involved in the process. I want to express my gratitude, firstly, to my mentor Lutz E. -

'Listen, the Jews Are Ruling Us Now': Antisemitism and National Conflict

B02 POLIN 25 TEXT 2/5/12 09:05 Page 305 ccccccccccccccccdxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx ‘Listen, the Jews are Ruling Us Now ’ Antisemitism and National Conflict during the First Soviet Occupation of Lithuania, 1940– 1941 . : O 1940 Ignas Šeinius, one of Lithuania’s prominent writers and the Red Cross representative in Vilnius, returned to Kaunas. The trip proved difficult: ‘As far as the eye can see . the dust rose like smoke from the road, choked with Bolsheviks and their vehicles. It was impossible to get around them, the dust infused with the unbearable smell of petrol and sweat .’ A mounted Red Army officer, ‘himself layered with dust, atop a dust-armoured horse’, helped Šeinius’s official Mercedes-Benz through the log jam —the only bright moment in the depressing montage of the invasion which he painted in his literary memoir Red Deluge .1 Unable to persuade his cabinet to authorize military resistance and determined not to preside over the country’s surrender, President Antanas Smetona opted for exile. The leader of the nation left none too soon. The presidential motorcade set out for the German border on the afternoon of 15 June just as a Soviet aeroplane carrying the Kremlin’s viceroy for Lithuania, Molotov’s deputy Vladimir Dekanozov, touched down at Kaunas airport. 2 Augustinas Voldemaras, Smetona’s long-time arch -rival , foolishly took the opportunity to return from exile in France only to be summarily arrested by the NKVD and sent to Russia. 3 The exile of inter-war Lithuania’s two most prominent politicians, one voluntary, the other forced, signalled the political This chapter includes material from two previous works of mine: ‘Foreign Saviors, Native Disciples: Perspectives on Collaboration in Lithuania, 1940–1945’, in D. -

The Yiddishists

THE YIDDISHISTS OUR SERIES DELVES INTO THE TREASURES OF THE WORLD’S BIGGEST YIDDISH ARCHIVE AT YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH Left: Shmuel Lehman (centre), a collector of Jewish folklore, interviews members of the YIVO Folklore Collectors Circle, Warsaw, 1931; below: Russ and Daughters Cafe Zoom Seder attended by YIVO staff members restructured my days to orient around marking time in a Jewish way.” Above all, each story acknowledges that Jewish life has changed: from not being with family for the Passover Seder to keeping chametz [foods with leavening agents that are traditionally banned during Passover] in the house over Passover due to concerns about access to food, to gathering on porches to make a minyan (prayer quorum) three times a day, as reported by one person from a chasidic community in Brooklyn. Even the youngest respondent, an eight-year-old girl who filled out the form with the help of her older sister, is conscious of these changes: “We didn’t eat the same horseradish that Savta [grandma] makes. We used onion grass collected LIFE DURING THE PANDEMIC from the lawn. We ate a different matzah.” These responses provide insight into the From prayers on Brooklyn porches to Zoom Passovers, Jewish ingenuity and resilience that has always THE YIDDISHISTS communities are adapting to life with Covid-19. Stefanie Halpern defined aspects of Jewish life. Gathering stories directly from the reports on a new initiative that is telling their stories Jewish community has always been at the core of YIVO’s mission. Since the n a cold evening in early April world. -

ANNUAL GATHERING COMMEMORATING the WARSAW GHETTO UPRISING 75Th Anniversary April 19, 2018

ANNUAL GATHERING COMMEMORATING THE WARSAW GHETTO UPRISING 75th Anniversary April 19, 2018 at Der Shteyn —The Stone Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Plaza Riverside Park, New York City ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Slucki’s speech “Th e Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and Its Legacy” appeared aft er the event in Tablet (online) on April 24, 2018 and is reprinted here with permission of the magazine. English excerpt from Hannah Krystal Fryshdorf’s 1956 unpublished Yiddish manuscript reprinted with permission of the translator Arthur Krystal. English excerpt from Chava Rosenfarb’s Th e Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto — Book Th ree: Th e Cattle Cars Are Waiting, 1942–1944, copyright © 1985, is reprinted with permission of Goldie Morgentaler. Th e poem “Delayed” from Spóźniona/Delayed, copyright © 2016, is reprinted with permission of the poet Irit Amiel and translator Marek Kazmierski. Th e poem “about my father” by Irena Klepfi sz copyright © 1990 is reprinted by permission of Irena Klepfi sz. Excerpt from David Fishman’s Th e Book Smugglers: Partisans, Poets, and the Race to Save Jewish Treasures from the Nazis, copyright © 2017, is reprinted with permission of David Fishman. Photos: Front cover and p. 16 courtesy of Ettie Mendelsund Goldwasser; facing p. 1, courtesy of Agi Legutko; p. 2 and 29 courtesy of Alamy; p. 34, courtesy of Irena Klepfi sz; p. 54 (Augenfeld) courtesy of Rivka Augenfeld; p. 42 (Blit) courtesy of Nelly Blit Dunkel; back cover courtesy of Marcel Kshensky. Th e following photos are courtesy of Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York: Eastern and Western Wall of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Memorial, Warsaw, pp.